4.8 The Molecular Mechanism of Crossing Over

In this chapter we have analyzed the genetic consequences of the cytologically visible process of crossing over without worrying about the mechanism of crossing over. However, crossing over is remarkable in itself as a molecular process: how can two large coiled molecules of DNA exchange segments with a precision so exact that no nucleotides are lost or gained?

Studies on fungal octads gave a clue. Although most octads show the expected 4:4 segregation of alleles such as 4A : 4a, some rare octads show aberrant ratios. There are several types, but as an example we will use 5:3 octads (either 5A : 3a or 5a : 3A). Two things are peculiar about this ratio. First, there is one too many spores of one allele and one too few of the other. Second, there is a nonidentical sister-

A-

(the hyphens show sister spores). In contrast, an aberrant 5A : 3a octad must be

A-

In other words, there is one nonidentical sister-

The observation of a nonidentical sister-

GCTAATGTTATTAG

CGATTATAATAATC

At replication to form an octad, a G : T heteroduplex would pull apart and replicate faithfully, with G bonding to C and A bonding to T. The result would be a nonidentical spore pair of G : C (allele A) and A : T (allele a).

Nonidentical sister spores (and aberrant octads generally) were found to be statistically correlated with crossing over in the region of the gene concerned, providing an important clue that crossing over might be based on the formation of heteroduplex DNA.

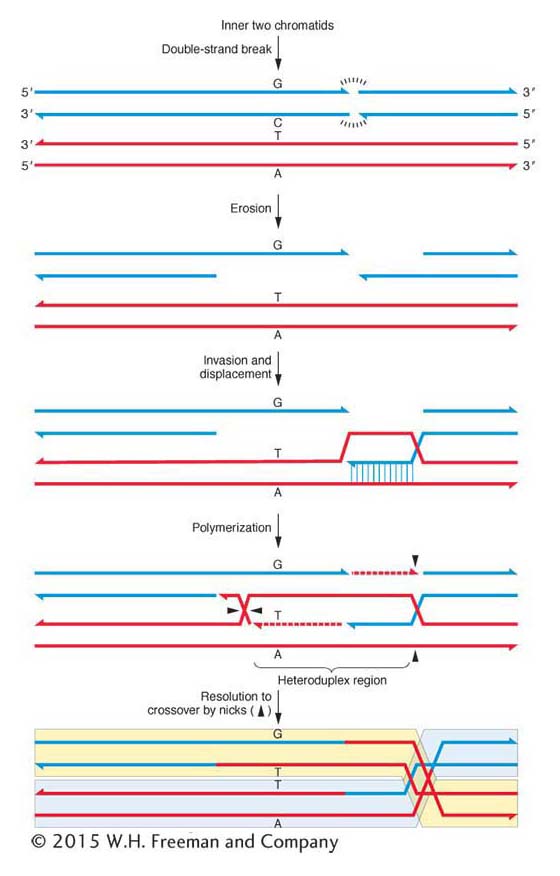

In the currently accepted model (follow it in Figure 4-21), the heteroduplex DNA and a crossover are both produced by a double-stranded break in the DNA of one of the chromatids participating in the crossover. Let’s see how that works. Molecular studies show that broken ends of DNA will promote recombination between different chromatids. In step 1, both strands of a chromatid break in the same location. From the break, DNA is eroded at the 5′ end of each broken strand, leaving both 3′ ends single stranded (step 2). One of the single strands “invades” the DNA of the other participating chromatid; that is, it enters the center of the helix and base-

Note that when the invading strand uses the invaded DNA as a replication template, this automatically results in an extra copy of the invaded sequence at the expense of the invading sequence, thus explaining the departure from the expected 4:4 ratio.

This same sort of recombination takes place at many different chromosomal sites where the invasion and strand displacement do not span a heterozygous mutant site. Here DNA would be formed that is heteroduplex in the sense that it is composed of strands of each participating chromatid, but there would not be a mismatched nucleotide pair and the resulting octad would contain only identical spore pairs. Those rare occasions in which the invasion and polymerization do span a heterozygous site are simply lucky cases that provided the clue for the mechanism of crossing over.