| Genetic "Vital Statistics" | |

|---|---|

|

Genome size: |

97 Mb |

|

Chromosomes: |

5 autosomes (2n = 10), X chromosome |

|

Number of genes: |

19,000 |

|

Percentage with human homologs: |

25% |

|

Average gene size: |

5 kb, 5 exons/gene |

|

Transposons: |

Several types, active in some strains |

|

Genome sequenced in: |

1998 |

Caenorhabditis elegans

Key organism for studying:

Development

Behavior

Nerves and muscles

Aging

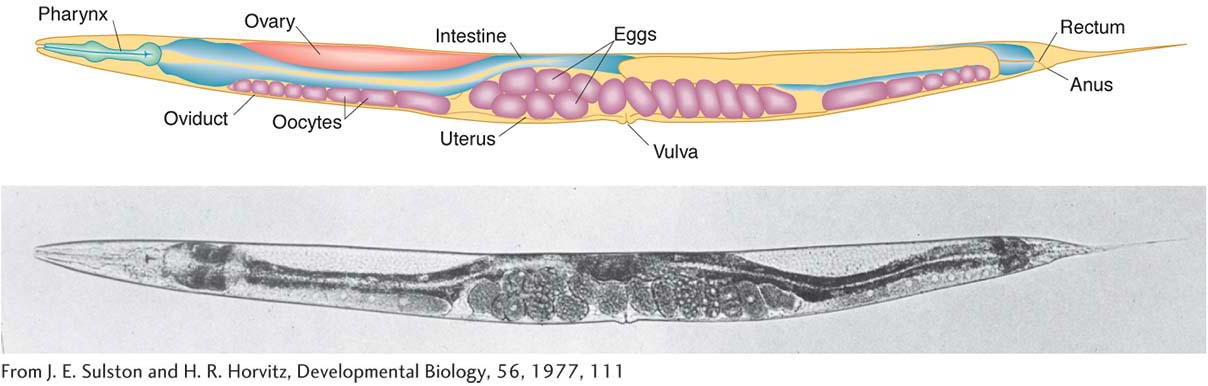

Caenorhabditis elegans may not look like much under a microscope, and, indeed, this 1-

Special features

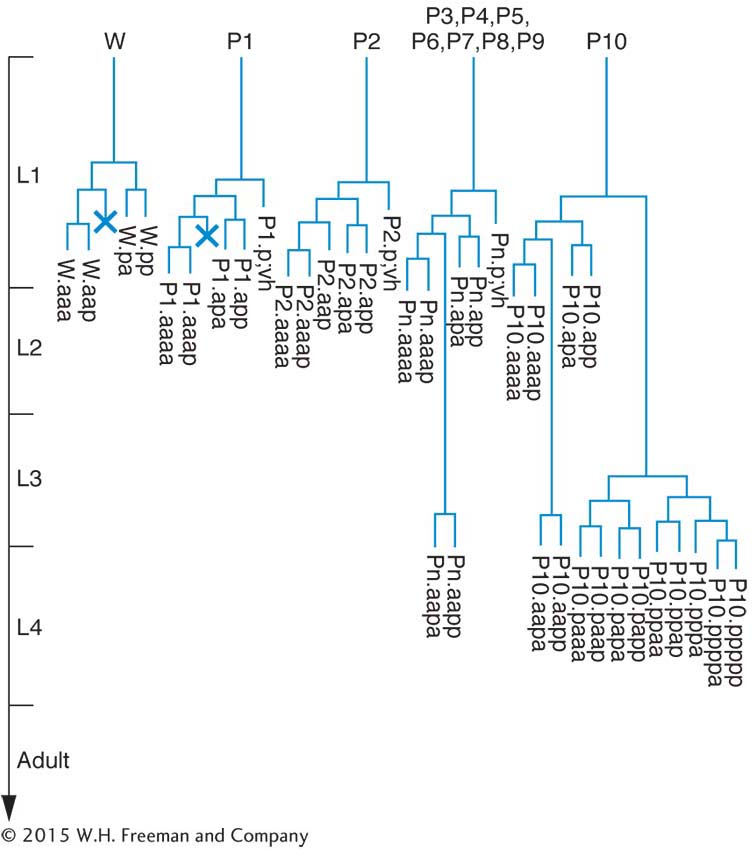

Geneticists can see right through C. elegans. Unlike other multicellular model organisms, such as fruit flies or Arabidopsis, this tiny worm is transparent, making it efficient to screen large populations for interesting mutations affecting virtually any aspect of anatomy or behavior. Transparency also lends itself well to studies of development: researchers can directly observe all stages of development simply by watching the worms under a light microscope. The results of such studies have shown that C. elegants development is tightly programmed and that each worm has a surprisingly small and consistent number of cells (959 in hermaphrodites and 1031 in males). In fact, biologists have tracked the fates of specific cells as the worm develops and have determined the exact pattern of cell division leading to each adult organ. This effort has yielded a lineage pedigree for every adult cell.

Life Cycle

C. elegans is unique among the major model animals in that one of the two sexes is hermaphrodite (XX). The other is male (XO). The two sexes can be distinguished by the greater size of the hermaphrodites and by differences in their sex organs. Hermaphrodites produce both eggs and sperm, and so they can be selfed. The progeny of a selfed hermaphrodite also are hermaphrodites, except when a rare nondisjunction leads to an XO male. If hermaphrodites and males are mixed, the sexes copulate, and many of the resulting zygotes will have been fertilized by the males’ amoeboid sperm. Fertilization and embryo production take place within the hermaphrodite, which then lays the eggs. The eggs finish their development externally.

Total length of life cycle: 3½ days

Genetic analysis

Because the worms are small and reproduce quickly and prolifically (selfing produces about 300 progeny and crossing yields about 1000), they produce large populations of progeny that can be screened for rare genetic events. Moreover, because hermaphroditism in C. elegans makes selfing possible, individual worms with homozygous recessive mutations can be recovered quickly by selfing the progeny of treated individual worms. In contrast, other animal models, such as fruit flies or mice, require matings between siblings and take more generations to recover recessive mutations.

Techniques of Genetic Modification

|

Standard mutagenesis: |

|

|

Chemical (EMS) and radiation |

Random germ- |

|

Transposons |

Random germ- |

|

Transgenesis: |

|

|

Transgene injection of gonad |

Unintegrated transgene array; occasional integration |

|

Targeted gene knockouts: |

|

|

Transposon- |

Knockouts selected with PCR |

|

RNAi |

Mimics targeted knockout |

|

Laser ablation |

Knockout of one cell |

Genetic engineering

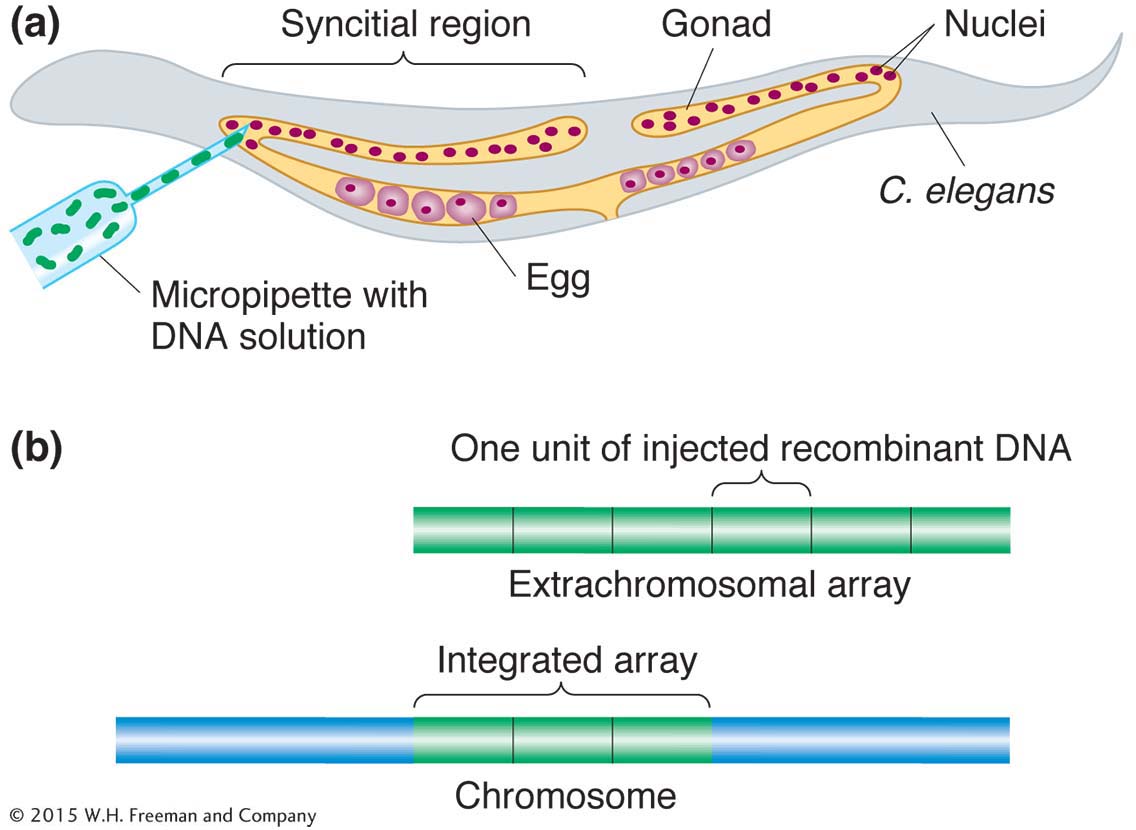

Transgenesis. The introduction of transgenes into the germ line is made possible by a special property of C. elegans gonads. The gonads of the worm are syncitial, meaning that there are many nuclei in a common cytoplasm. The nuclei do not become incorporated into cells until meiosis, when formation of the individual egg or sperm begins. Thus, a solution of DNA containing the transgene injected into the gonad of a hermaphrodite exposes more than 100 germ-

Transgenes recombine to form multicopy tandem arrays. In an egg, the arrays do not integrate into a chromosome, but transgenes from the arrays are still expressed. Hence, the gene carried on a wild-

Targeted knockouts. In strains with active transposons, the transposons themselves become agents of mutation by inserting into random locations in the genome, knocking out the interrupted genes. If we can identify organisms with insertions into a specific gene of interest, we can isolate a targeted gene knockout. Inserts into specific genes can be detected by using PCR if one PCR primer is based on the transposon sequence and another one is based on the sequence of the gene of interest. Alternatively, RNAi can be used to nullify the function of specific genes. As an alternative to mutation, individual cells can be killed by a laser beam to observe the effect on worm function or development (laser ablation).

Main contributions

C. elegans has become a favorite model organism for the study of various aspects of development because of its small and invariant number of cells. One example is programmed cell death, a crucial aspect of normal development. Some cells are genetically programmed to die in the course of development (a process called apoptosis). The results of studies of C. elegans have contributed a useful general model for apoptosis, which is also known to be a feature of human development.

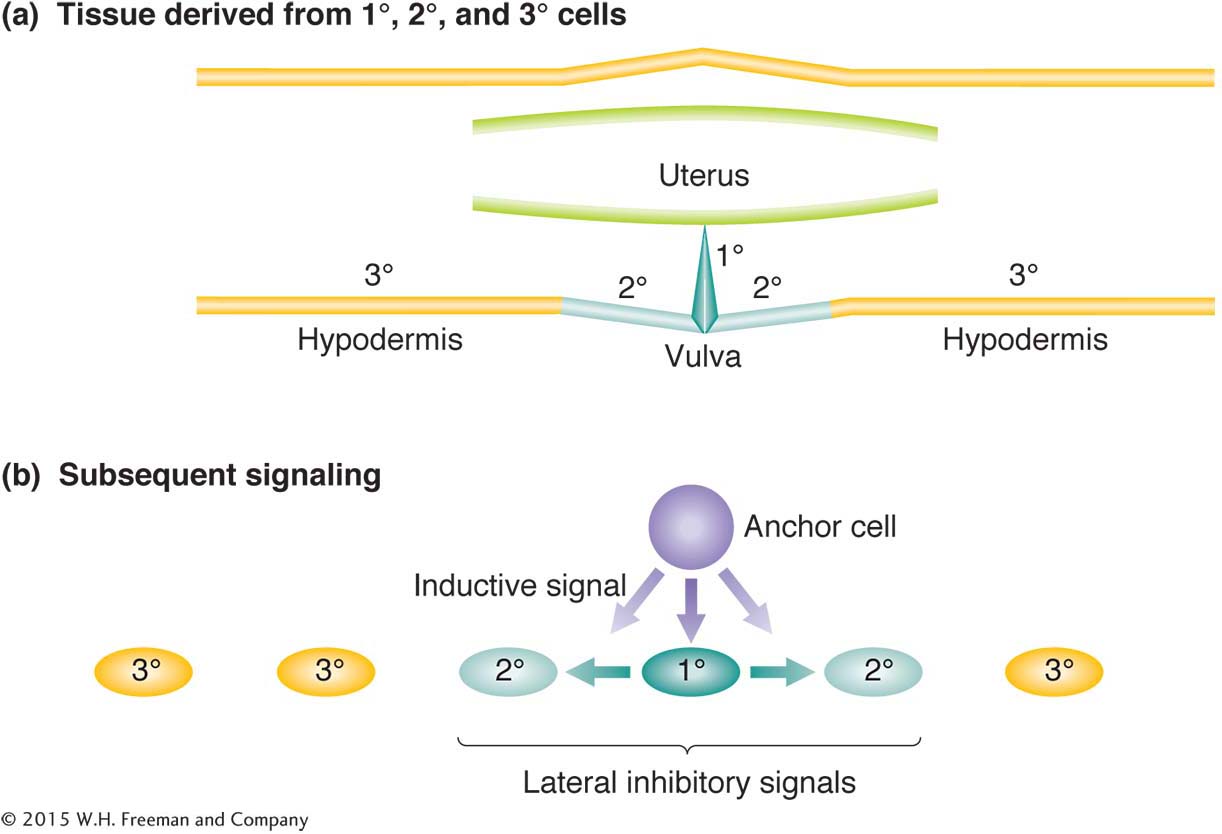

Another model system is the development of the vulva, the opening to the outside of the reproductive tract. Hermaphrodites with defective vulvas still produce progeny, which in screens are easily visible clustered within the body. The results of studies of hermaphrodites with no vulva or with too many have revealed how cells that start off completely equivalent can become differentiated into different cell types.

Behavior also has been the subject of genetic dissection. C. elegans offers an advantage in that worms with defective behavior can often still live and reproduce. The worm’s nerve and muscle systems have been genetically dissected, allowing behaviors to be linked to specific genes.

Other area of contribution

Cell-

to- cell signaling