16.3 The Molecular Basis of Induced Mutations

Whereas some mutations are spontaneously produced inside the cell, other sources of mutation are present in the environment, whether intentionally applied in the laboratory or accidentally encountered in the course of everyday life. The production of mutations in the laboratory through exposure to mutagens is called mutagenesis, and the organism is said to be mutagenized.

Mechanisms of mutagenesis

Mutagens induce mutations by at least three different mechanisms. They can replace a base in the DNA, alter a base so that it specifically mispairs with another base, or damage a base so that it can no longer pair with any base under normal conditions. Mutagenizing genes and observing the phenotypic consequences is one of the primary experimental strategies used by geneticists.

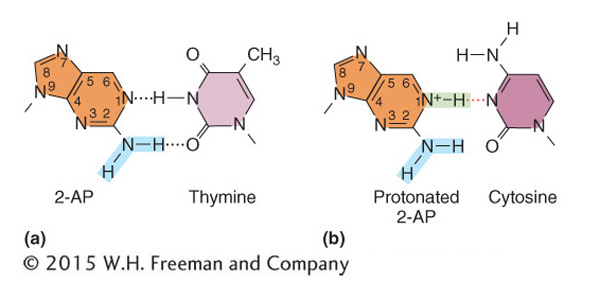

Incorporation of base analogs Some chemical compounds are sufficiently similar to the normal nitrogen bases of DNA that they occasionally are incorporated into DNA in place of normal bases; such compounds are called base analogs. After they are in place, these analogs have pairing properties unlike those of the normal bases; thus, they can produce mutations by causing incorrect nucleotides to be inserted opposite them in replication. The original base analog exists in only a single strand, but it can cause a nucleotide-

One base analog widely used in research is 2-

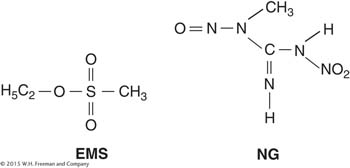

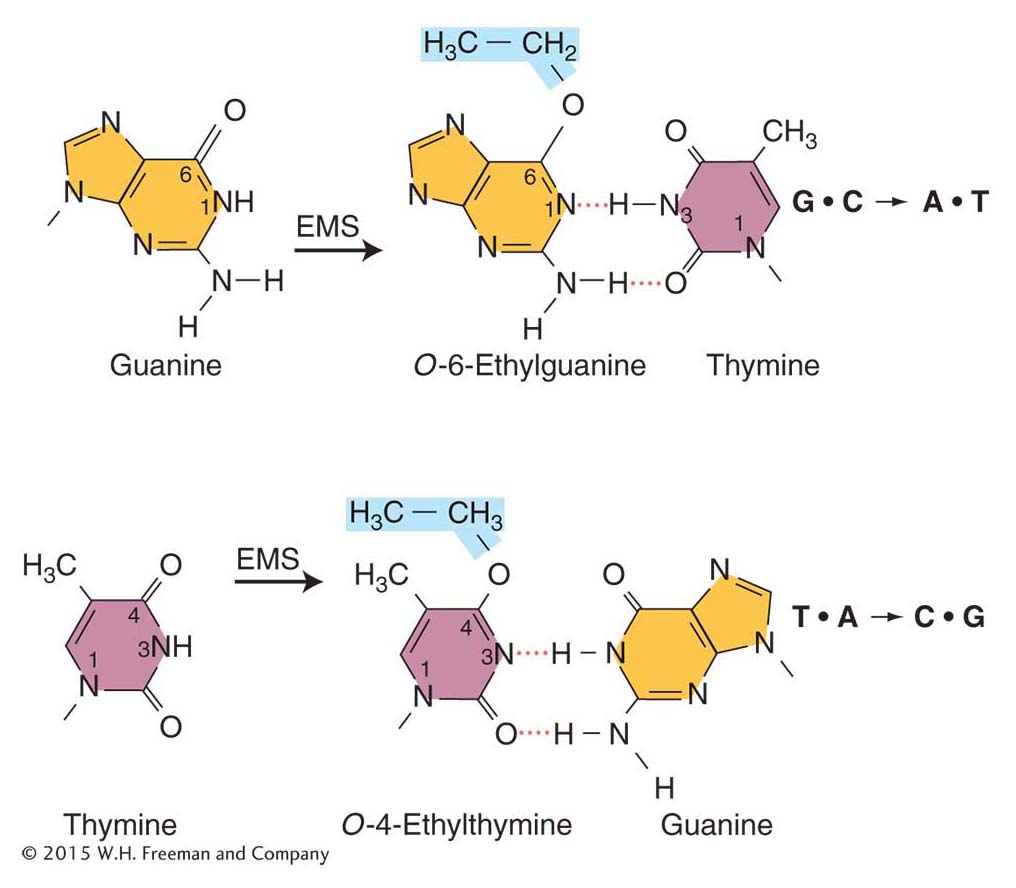

Specific mispairing Some mutagens are not incorporated into the DNA but instead alter a base in such a way that it will form a specific mispair. Certain alkylating agents, such as ethylmethanesulfonate (EMS) and the widely used nitrosoguanidine (NG), operate by this pathway.

Such agents add alkyl groups (an ethyl group in EMS and a methyl group in NG) to many positions on all four bases. However, the formation of a mutation is best correlated with an addition to the oxygen at position 6 of guanine to create an O-6-

Alkylating agents can also modify the bases in dNTPs (where N is any base), which are precursors in DNA synthesis.

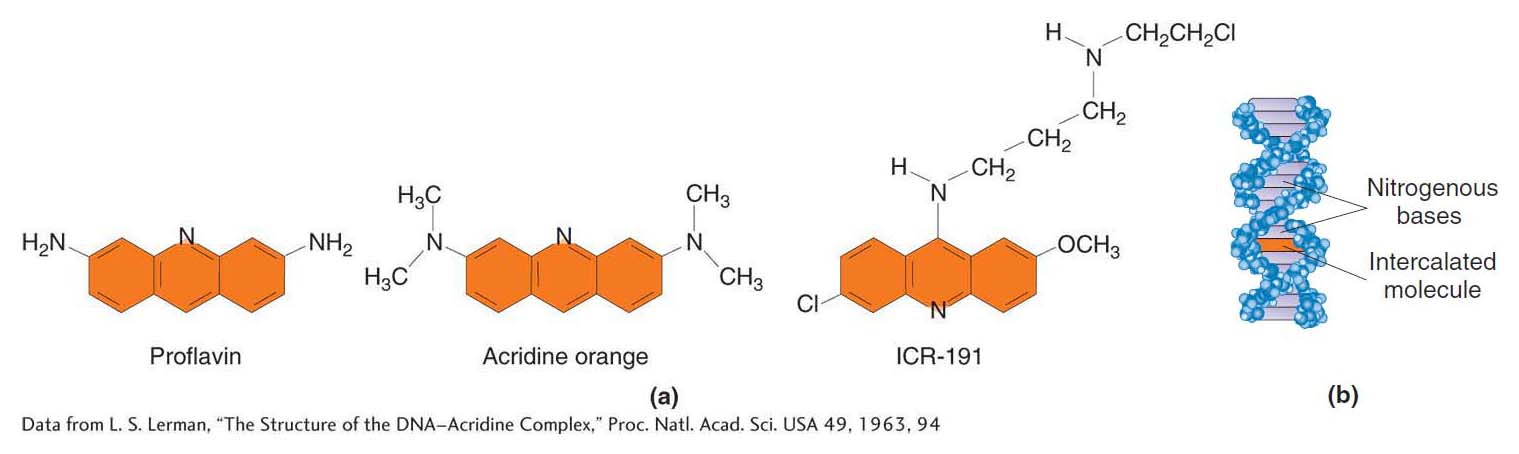

Intercalating agents The intercalating agents form another important class of DNA modifiers. This group of compounds includes proflavin, acridine orange, and a class of chemicals termed ICR compounds (Figure 16-14a). These agents are planar molecules that mimic base pairs and are able to slip themselves in (intercalate) between the stacked nitrogen bases at the core of the DNA double helix (Figure 16-14b). In this intercalated position, such an agent can cause an insertion or deletion of a single nucleotide pair.

Base damage A large number of mutagens damage one or more bases, and so no specific base pairing is possible. The result is a replication block because DNA synthesis will not proceed past a base that cannot specify its complementary partner by hydrogen bonding. Replication blocks can cause further mutation—

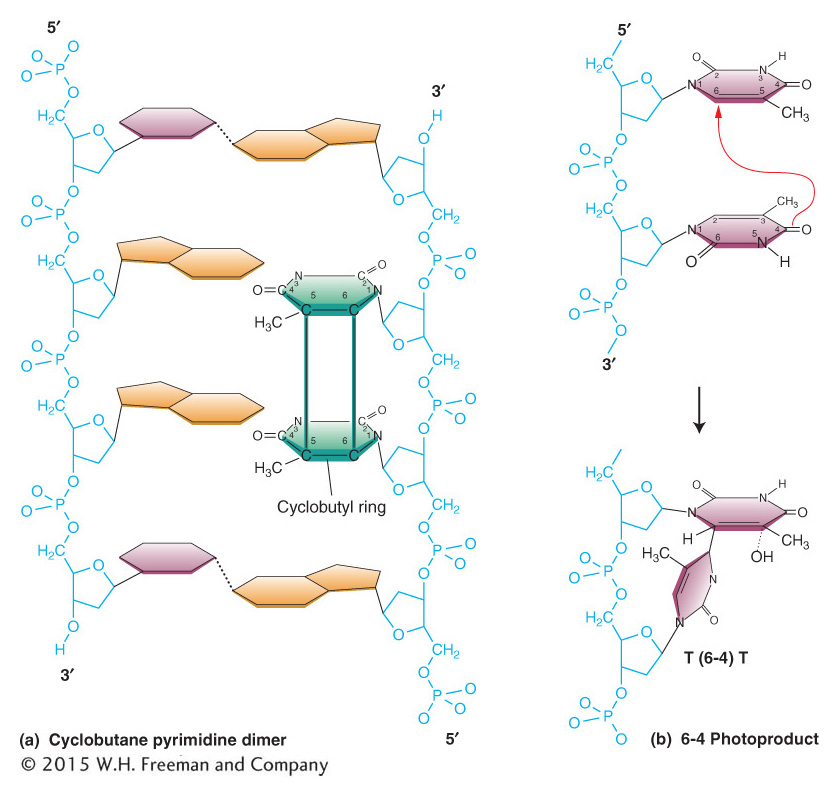

Ultraviolet light usually causes damage to nucleotide bases in most organisms. Ultraviolet light generates a number of distinct types of alterations in DNA, called photoproducts (from the word photo, for “light”). The most likely of these products to lead to mutations are two different lesions that unite adjacent pyrimidine residues in the same strand. These lesions are the cyclobutane pyrimidine photodimer and the 6-

Ionizing radiation results in the formation of ionized and excited molecules that can damage DNA. Because of the aqueous nature of biological systems, the molecules generated by the effects of ionizing radiation on water produce the most damage. Many different types of reactive oxygen species are produced, but the most damaging to DNA bases are · OH, O2–, and H2O2. These species lead to the formation of different adducts and degradation products. Among the most prevalent, pictured in Figure 16-9, are thymidine glycol and 8-

Ionizing radiation can also damage DNA directly rather than through reactive oxygen species. Such radiation may cause breakage of the N-

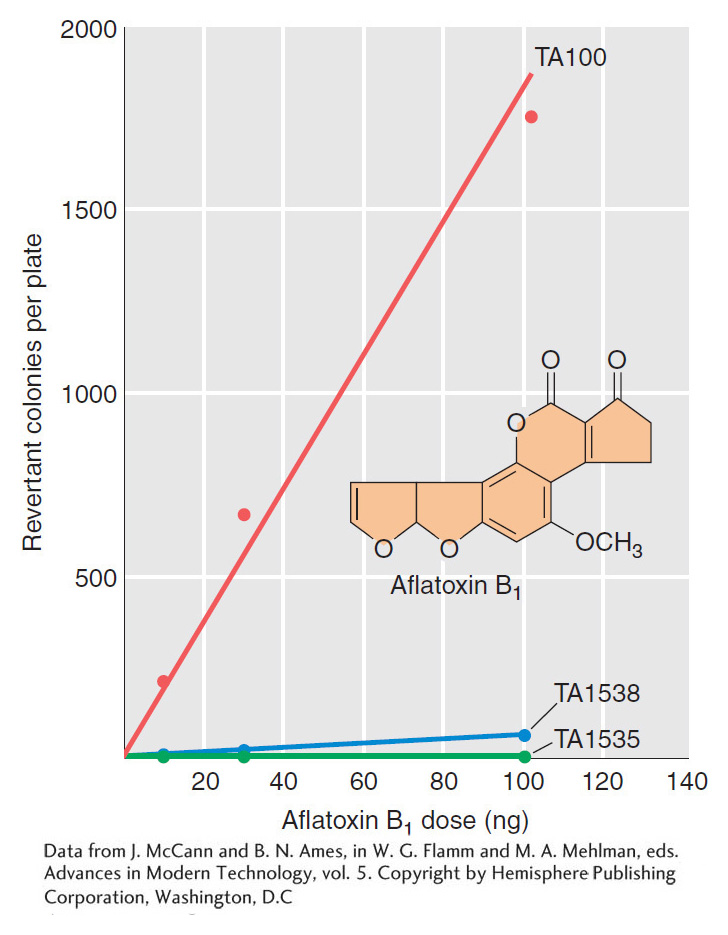

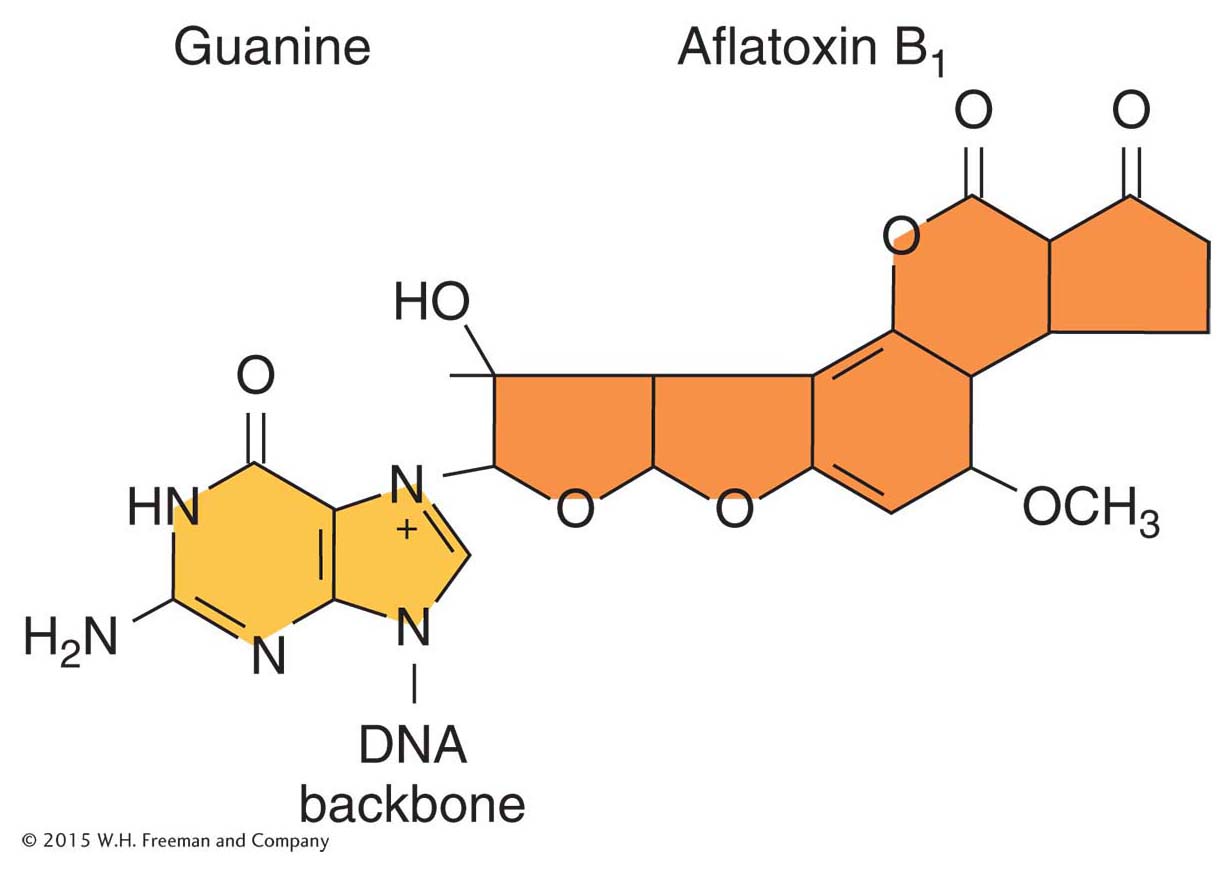

Aflatoxin B1 is a powerful carcinogen that attaches to guanine at the N-

KEY CONCEPT

Mutagens induce mutations by a variety of mechanisms. Some mutagens mimic normal bases and are incorporated into DNA, where they can mispair. Others damage bases and either cause specific mispairing or destroy pairing by causing nonrecognition of bases.The Ames test: evaluating mutagens in our environment

A huge number of chemical compounds have been synthesized, and many have possible commercial applications. We have learned the hard way that the potential benefits of these applications have to be weighed against health and environmental risks. Thus, having efficient screening techniques to assess some of the risks of a large number of compounds is essential.

Many compounds are potential cancer-

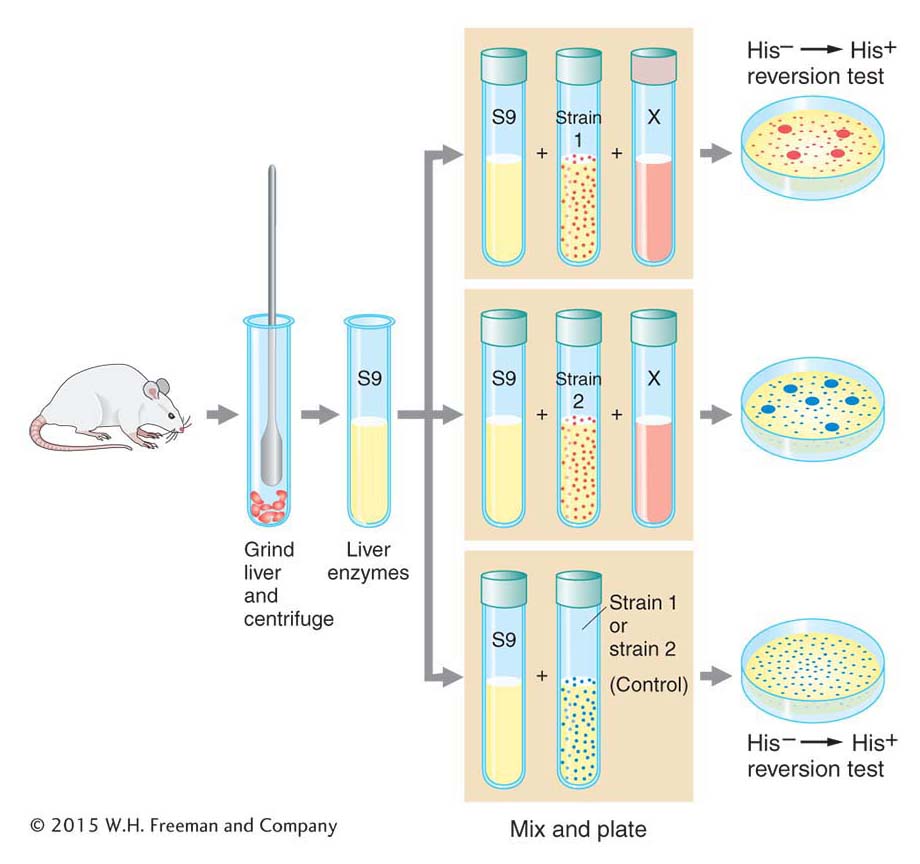

In the 1970s, Bruce Ames recognized that there is a strong correlation between the ability of compounds to cause cancer and their ability to cause mutations. He surmised that measurement of mutation rates in bacterial systems would be an effective model for evaluating the mutagenicity of compounds as a first level of detection of potential carcinogens. However, it became clear that not all carcinogens were themselves mutagenic; rather, some carcinogens’ metabolites produced in the body are actually the mutagenic agents. Typically, these metabolites are produced in the liver, and the enzymatic reactions that convert the carcinogens into the bioactive metabolites did not take place in bacteria.

Ames realized that he could overcome this problem by treating special strains of the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium with extracts of rat livers containing metabolic enzymes (Figure 16-17). The special strains of S. typhimurium had one of several mutant alleles of a gene responsible for histidine synthesis that were known to “revert” (that is, return to wild-

The treated bacteria of each of these strains were exposed to the test compound, then grown on petri plates containing medium lacking histidine. The absence of this nutrient ensured that only revertant individuals containing the appropriate base substitution or frameshift mutation would grow. The number of colonies on each plate and the total number of bacteria tested were determined, allowing Ames to measure the frequency of reversion. Compounds that yielded metabolites inducing elevated levels of reversion relative to untreated control liver extracts would then clearly be mutagenic and would be possible carcinogens. The Ames test thus provided an important way of screening thousands of compounds and evaluating one aspect of their risk to health and the environment. It is still in use today as an important tool for the evaluation of the safety of chemical compounds.