Appropriateness

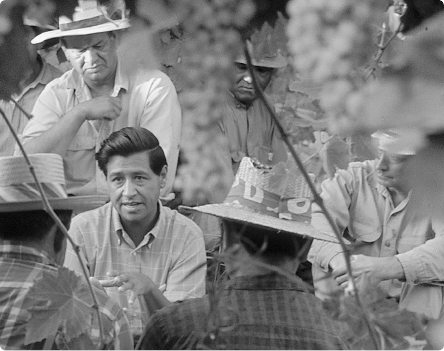

Whether speaking with union volunteers or powerful politicians, labor leader César Chávez’s interpersonal communication competence allowed him to translate his personal intentions into actions that benefitted America’s poorest farm laborers and changed the world.

Arthur Schatz/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

The first characteristic of competent interpersonal communication is appropriateness—the degree to which your communication matches situational, relational, and cultural expectations regarding how people should communicate. In any interpersonal encounter, norms exist regarding what people should and shouldn’t say, and how they should and shouldn’t act. Part of developing your communication competence is refining your sensitivity to norms and adapting your communication accordingly. People who fail to do so are perceived by others as incompetent communicators.

We judge how appropriate our communication is through self-monitoring  : the process of observing our own communication and the norms of the situation in order to make appropriate communication choices. Some individuals closely monitor their own communication to ensure they’re acting in accordance with situational expectations (Giles & Street, 1994). Known as high self-monitors, they prefer situations in which clear expectations exist regarding how they’re supposed to communicate. In contrast, low self-monitors don’t assess their own communication or the situation. They prefer encounters in which they can “act like themselves” rather than having to abide by norms (Snyder, 1974).

: the process of observing our own communication and the norms of the situation in order to make appropriate communication choices. Some individuals closely monitor their own communication to ensure they’re acting in accordance with situational expectations (Giles & Street, 1994). Known as high self-monitors, they prefer situations in which clear expectations exist regarding how they’re supposed to communicate. In contrast, low self-monitors don’t assess their own communication or the situation. They prefer encounters in which they can “act like themselves” rather than having to abide by norms (Snyder, 1974).

While communicating appropriately is a key part of competence, overemphasizing appropriateness can backfire. If you focus exclusively on appropriateness and always adapt your communication to what others want, you may end up forfeiting your freedom of communicative choice to peer pressure or fears of being perceived negatively (Burgoon, 1995).