Culture and Self

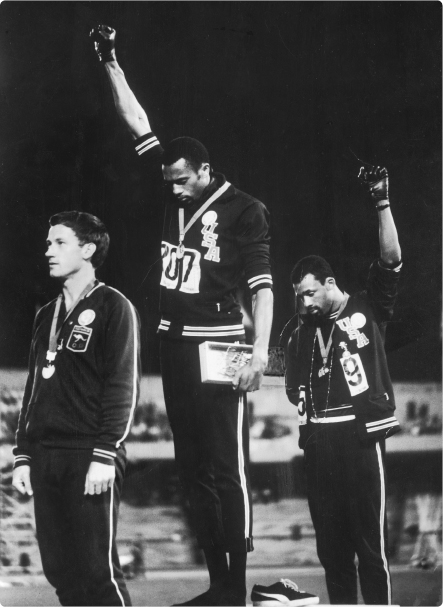

Tommie Smith’s and John Carlos’ protest at the 1968 Summer Olympics showed how they identified with the African American culture of the time.

John Dominis/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

At the 1968 Summer Olympics, U.S. sprinter Tommie Smith won the men’s 200-meter gold medal, and teammate John Carlos won the bronze. During the medal ceremony, as the American flag was raised and “The Star-Spangled Banner” played, both runners closed their eyes, lowered their heads, and raised black-gloved fists. Smith’s right fist represented black power, and Carlos’ left fist represented black unity (Gettings, 2005). The two fists, raised next to each other, created an arch of black unity and power. Smith wore a black scarf around his neck for black pride, and both men wore black socks with no shoes, representing African American poverty. These symbols and gestures, taken together, clearly spoke of the runners’ allegiance to black culture and their protest of the poor treatment of African Americans in the United States (see the photo to the right).

Many Euro-Americans viewed Smith’s and Carlos’ behavior at the ceremony as a betrayal of “American” culture. Both men were suspended from the U.S. team; they and their families began receiving death threats. Over time, however, people of all American ethnicities began to sympathize with them, and, 30 years later, in 1998, Smith and Carlos were commemorated in an anniversary celebration of their protest.

In addition to gender and family, our culture is a powerful source of self. Culture is an established, coherent set of beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices shared by a large group of people (Keesing, 1974). If this strikes you as similar to our definition of self-concept, you’re right; culture is like a collective sense of self shared by a large group of people.

Thinking of culture in this way has important implications. First, it includes many different types of large-group influences, including your nationality as well as your ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, physical abilities, and even age. We learn our cultural beliefs, attitudes, and values from parents, teachers, religious leaders, peers, and the mass media (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). Most of us belong to more than one culture simultaneously—possessing the beliefs, attitudes, and values of each. Unfortunately, the various cultures to which we belong sometimes clash; when they do, we often have to choose the culture to which we pledge our primary allegiance.

We’ll be discussing culture in greater depth in Chapter 5, where we’ll consider some of the unique variables of culture that help to define us and communicate our selves to others.

Self-Reflection

When you consider your own cultural background, to which culture do you “pledge allegiance”? How do you communicate this allegiance to others? Have you ever suffered consequences for openly communicating your allegiance to your culture? If so, how?

Question

Self-Reflection

Cultural identity is part of a sophisticated definition of self.

(Left to right) West Rock/Getty Images; © Image Source/Alamy; John Elk III/Alamy; © Paul A. Souders/Corbis