Feelings and Moods

We often talk about emotions, feelings, and moods as if they are the same thing. But they’re not. Feelings are short-term emotional reactions to events that generate only limited arousal; they typically do not trigger attempts to manage their experience or expression (Berscheid, 2002). We experience dozens, if not hundreds, of feelings daily—most of them lasting only a few seconds or minutes. For example, a friend texts you unexpectedly when you’re trying to study, making you feel briefly annoyed. Feelings are like “small emotions.” Common feelings include gratitude, concern, pleasure, relief, and resentment.

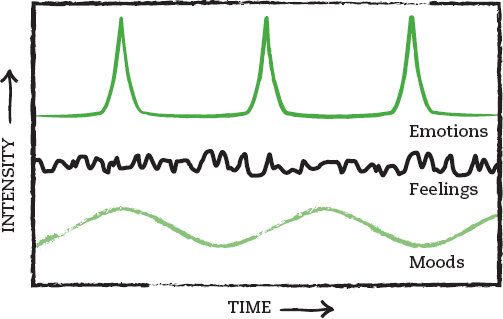

Whereas emotions occur occasionally in response to substantial events, and feelings arise frequently in response to everyday incidents, moods are different. Moods are low-intensity states—such as boredom, contentment, grouchiness, or serenity—that are not caused by particular events and typically last longer than feelings or emotions (Parkinson, Totterdell, Briner, & Reynolds, 1996). Positive or negative, moods are the slow-flowing emotional currents in our everyday lives. We can think of our frequent, fleeting feelings and occasional intense emotions as riding on top of these currents, as displayed in Figure 4.1.

Moods powerfully influence our perception and interpersonal communication. People who describe their moods as “good” are more likely to form positive impressions of others than those who report being in “bad” moods (Forgas & Bower, 1987). Similarly, people in good moods are more likely than those in bad moods to perceive new acquaintances as sociable, honest, giving, and creative (Fiedler, Pampe, & Scherf, 1986). Our moods also influence how we talk with partners in close relationships (Cunningham, 1988). People in good moods are significantly more likely to disclose relationship thoughts and concerns to close friends, family members, and romantic partners. People in bad moods typically prefer to sit and think, to be left alone, and to avoid social and leisure activities (Cunningham, 1988).

Your mood’s profound effect on your perception and interpersonal communication suggests that it’s important to learn how to shake yourself out of a bad mood (Thayer, Newman, & McClain, 1994). Effective strategies for elevating mood are active ones, especially strategies that combine relaxation, stress management, mental focus and energy, and exercise. The most effective strategy of all appears to be rigorous physical exercise (Thayer et al., 1994). Sexual activity does not seem to consistently elevate mood.

Self-Reflection

How do you behave toward others when you’re in a bad mood? What strategies do you use to better your mood? Are these practices effective in elevating your mood and improving your communication in the long run, or do they merely provide a temporary escape or distraction?

Question

Self-Reflection

It can be tempting to improve bad moods by drinking alcohol or caffeinated beverages, taking recreational drugs, or eating. However, studies show that one of the best ways to feel better is through physical exercise.

AP Photo/Pat Sullivan