Origin and Diffusion of the City

Origin and Diffusion of the City

As we noted in opening this chapter, we are entering an era when more people live in cities than live in rural areas. When cities first began, only a very small portion of the population lived in them. Over time cities began to diffuse throughout the globe, and established cities grew larger. In this section, we analyze two aspects of diffusion in regard to urbanization. First, we take a historical look at the origins of city life and explore how, why, and where cities diffused around the world. Second, we examine the more contemporary processes of rural-to-urban migration.

281

In seeking explanations for the origin of cities, we ultimately find a relationship among areas of early agricultural development, permanent village settlements, the emergence of new social forms, and urban life. The first cities resulted from a complicated transition that took thousands of years.

As early people, originally hunters and gatherers, became more successful at gathering their resources and domesticating plants and animals, they began to settle, first semipermanently and then permanently. In the Middle East, where the first cities appeared, a network of permanent agricultural villages developed about 10,000 years ago. These farming villages were modest in size, rarely with more than 200 people, and were probably organized on a kinship basis. Jarmo, one of the earliest villages, located in present-day Iraq, had 25 permanent dwellings clustered near grain storage facilities.

Although small farming villages like Jarmo predate cities, it is wrong to assume that a simple quantitative change took place whereby villages slowly grew, first into towns and then into cities. True cities, then and now, differ qualitatively from agricultural villages. All the inhabitants of agricultural villages were involved in some way in food procurement—tending the fields or harvesting and preparing the crops. Cities, however, were more removed, both physically and psychologically, from everyday agricultural activities. Food was supplied to the city, but not all city dwellers were involved in obtaining it. Instead, city dwellers supplied other services, such as technical skills or religious interpretations considered important in a particular society. Cities, unlike agricultural villages, contained a class of people who were not directly involved in agricultural activities.

agricultural surplus The amount of food a society grows that exceeds the demands of its population.

social stratification The existence of distinct socioeconomic classes.

Two elements were necessary for this dramatic social change: the creation of an agricultural surplus and the development of a stratified social system. Surplus food, which is a food supply larger than the everyday needs of the population, is a prerequisite for supporting nonfarmers—people who work at administrative, military, or handicraft tasks. Social stratification, the existence of distinct socioeconomic classes, facilitates the collection, storage, and distribution of resources through well-defined channels of authority that can exercise control over goods and people. A society with these two elements—surplus food and a means of storing and distributing it—was set for urbanization.

Models for the Rise of Cities

Models for the Rise of Cities

One way to understand the transition from village life to city life is to model the development of urban life assuming that a single factor is the trigger behind the transition. The question that scholars ask is, “What activity could be so important to an agricultural society that its people would be willing to give some of their surplus to support a social class that specializes in that activity?” Next we discuss answers to that question.

Technical Factors

hydraulic civilization A civilization based on large-scale irrigation.

Technical Factors The hydraulic civilization model, developed by Karl Wittfogel, assumes that the development of large-scale irrigation systems was the prime mover behind urbanization and that a class of technical specialists were the first urban dwellers. Irrigating agricultural crops yielded more food, and this surplus supported the development of a large nonfarming population. A strong, centralized government backed by an urban-based military could expand its power into the surrounding areas. Farmers who resisted the new authority were denied water. Continued reinforcement of the power elite came from the need for organizational coordination to ensure continued operation of the irrigation system. Labor specialization developed. Some people farmed; others worked on the irrigation system. Still others became artisans, creating the implements needed to maintain the system, or administrative workers in the direct employ of the power elite’s court.

Although the hydraulic civilization model fits several areas where cities first arose—China, Egypt, and Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq)—it cannot be applied to all urban hearths. In parts of Mesoamerica, for example, an urban civilization blossomed without widespread irrigated agriculture and therefore without a class of technical experts.

Religious Factors

Religious Factors Geographer Paul Wheatley suggests that religion led to urbanization. In early agricultural societies, knowledge of such matters as meteorology and climate was considered an element of religion. Such societies depended on their religious leaders to interpret the heavenly bodies before deciding when and how to plant their crops. The propagation of this type of knowledge led to more successful harvests, which in turn allowed for the support of both a larger priestly class and a class of people engaged in ancillary activities. The priestly class exercised the political and social control that held the city together.

In this scenario, early cities were religious spaces. The first urban clusters and fortifications are seen as defenses not against human invaders but against spiritual ones: demons or the souls of the dead. This religious explanation is applicable in some ways to all of the early centers of urbanization, although it seems especially successful in explaining Chinese urbanization.

Political Factors

Political Factors Some scholars suggest that the centralizing force in urbanization was political order. Urban historian Lewis Mumford described the agent of change in emerging urban centers as the institution of kingship, which involved the centralizing of religious, social, and economic aspects of a civilization around a powerful figure who became known as the king. This figure of authority, who in the preurban world was accorded respect for his or her human abilities, ascended to almost superhuman status in early urbanizing societies. By exercising power, the king was able to marshal the labor of others. The resultant social hierarchy enabled the society to diversify its endeavors, with different groups specializing in crafts, farming, trading, or religious activity. The institution of kingship provided essential leadership and organization to this increasingly complex society, which became the city.

282

Multiple Factors

Multiple Factors At the onset of urbanization, and even much later in some places, sharp distinctions among economic, religious, and political functions were not always made. The king may also have functioned as priest, healer, astronomer, and scribe, thereby fusing secular and spiritual power. Critics of the kingship theory, therefore, point out that this explanation of urbanization may not be different from the religion-based model. Rather than attempting to isolate one trigger, a wiser course may be to accept the role of multiple factors behind the changes leading to urban life. Technical, religious, and political forces were often interlinked, with a change in one leading to changes in another. Instead of oversimplifying by focusing on one possible development schema, we must appreciate the complexities of the transition period from agricultural village to true city.

Urban Hearth Areas

Urban Hearth Areas

urban hearth area A region in which the world’s first cities evolved.

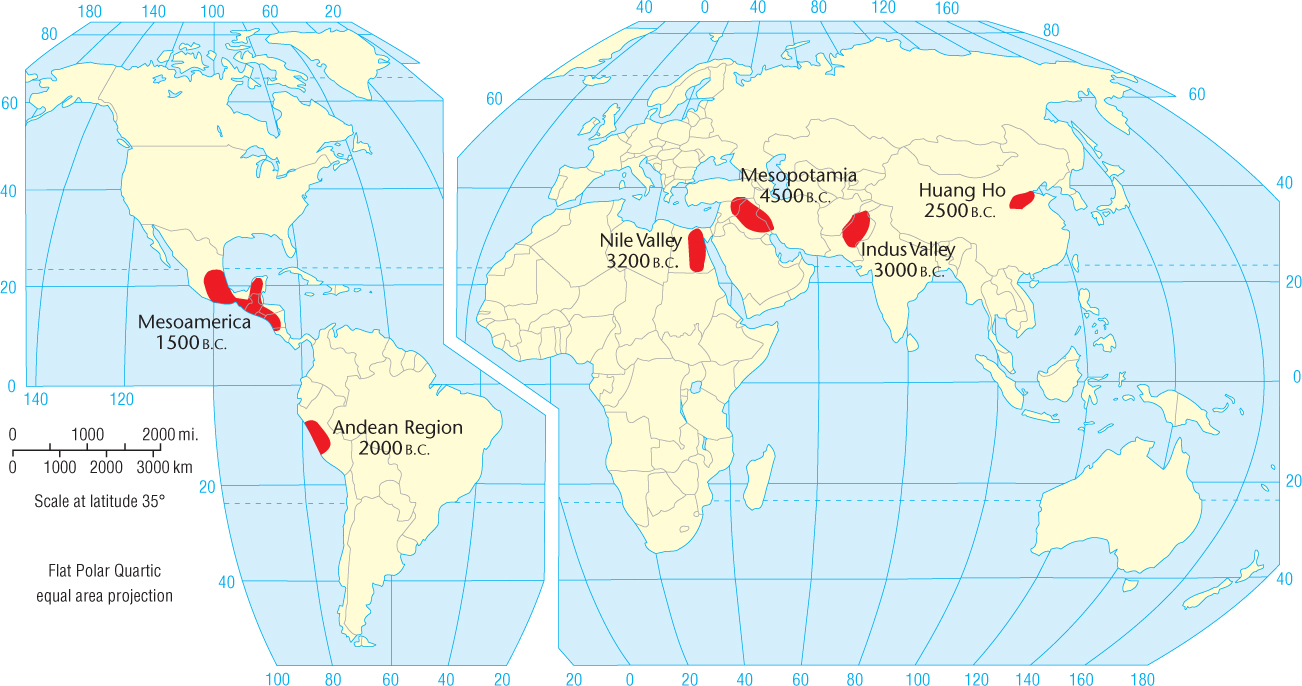

The first cities appeared in distinct regions, such as Mesopotamia, the Nile River valley, Pakistan’s Indus River valley, the Yellow River (or Huang Ho) valley of China, Mesoamerica, and the Andean highlands and coastal areas of Peru. These are called the urban hearth areas (Figure 10.3).

Reflecting on Geography

Question 10.4

Scholars are continually altering the dates for the emergence of urban life, as well as the location of the hearth areas. Why? Can you outline some of the reasons it is so difficult to pinpoint the places and dates for the emergence of urban life?

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.5

Compare this map with Figure 8.16. What similarities and differences do you notice?

It is generally agreed that the first cities arose in Mesopotamia, the river valley of the Tigris and Euphrates in what is now Iraq. Mesopotamian cities, small by current standards, covered 0.5 to 2 square miles (1.3 to 5 square kilometers) with populations that rarely exceeded 30,000. Nevertheless, the densities within these cities could easily reach 10,000 people per square mile (4000 per square kilometer), which is comparable to the densities in many contemporary cities.

283

cosmomagical city A type of city that is laid out in accordance with religious principles, characteristic of very early cities, particularly in China.

axis mundi The symbolic center of cosmomagical cities, often demarcated by a large, vertical structure.

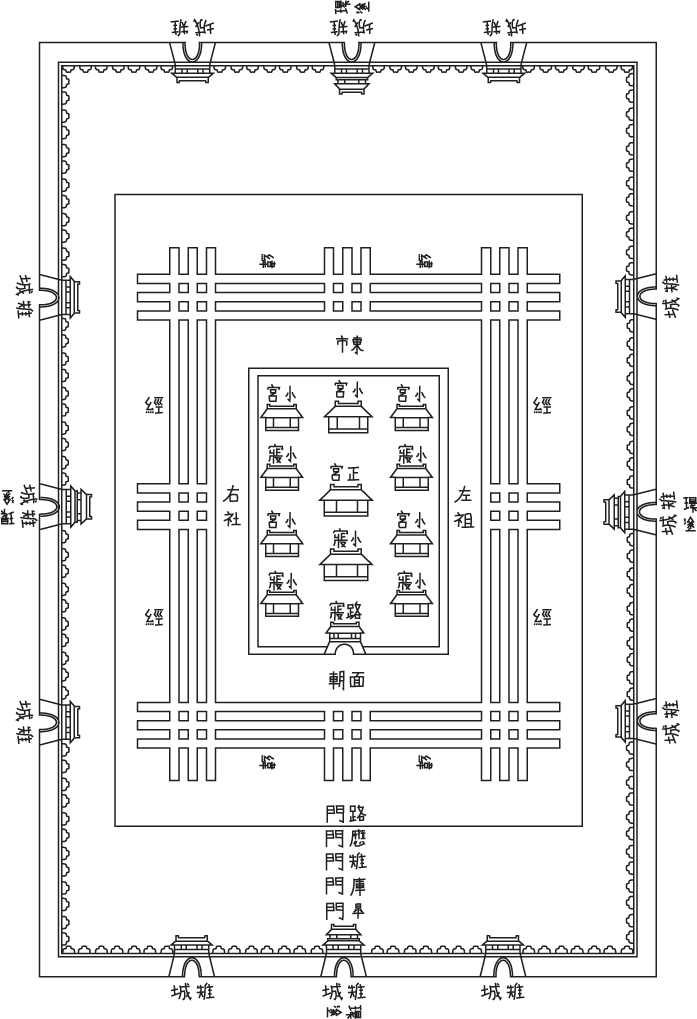

Scholars have referred to these first cities as cosmomagical cities, defined as cities that are spatially arranged according to religious principles. The spatial layouts of cosmomagical cities are similar in three important ways (Figure 10.4). First, great importance was accorded to the city’s symbolic center, which was also thought to be the center of the known world. It was therefore the most sacred spot and was often identified by a vertical structure of monumental scale that represented the point on Earth closest to the heavens. This symbolic center, or axis mundi, took the form of the ziggurat in Mesopotamia, the palace or temple in China, and the pyramid in Mesoamerica. Often this elevated structure, which usually served a religious purpose, was close to the palace or seat of political power and to the granary. These three structures were often walled off from the rest of the city, forming a symbolic center that both reflected the significance of these societal functions and dominated the city physically and spiritually (Figure 10.5. The Forbidden City in Beijing remains one of the best examples of this guarded, fortresslike city within the city. The second spatial characteristic common to cosmomagical cities is that they were oriented toward the four cardinal directions. By aligning the city in the north-south and east-west directions, the geometric form of the city reflected the order of the universe. This alignment, it was thought, would ensure harmony and order over the known world, which was bounded by the city walls.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.6

What do you think the gates to the city represent?

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.7

Why was the granary in the inner city?

In all of these early cities, one sees evidence of a third spatial characteristic: an attempt to shape the form of the city according to the form of the universe. This characteristic may have taken a literal form—a city laid out, for example, in a pattern of a major star constellation. Far more common, however, were cities that symbolically approximated mythical conceptions of the universe. Angkor Thom was an early city in Cambodia that presents one of the best examples of this parallelism. An urban cluster that spread over 6 square miles (15.5 square kilometers), Angkor Thom was a representation in stone of a series of religious beliefs about the nature of the universe.

Nevertheless, regional variations in the basic form certainly existed. For example, the early cities of the Nile were not walled, which suggests that a regional power structure kept individual cities from warring with one another. In the Indus Valley, the great city of Mohenjo-daro was laid out in a grid that consisted of 16 large blocks, and the citadel was located within the block that was central but situated toward the western edge.

The most important variations within the urban hearth areas occurred in Mesoamerican cities (Figure 10.6). Here, cities were less dense and covered large areas. Furthermore, these cities arose without benefit of the technological advances found in the other hearth areas, most notably the wheel, the plow, metallurgy, and draft animals. However, the domestication of maize compensated for these shortcomings. Maize is a grain that in tropical climates yields several crops a year without irrigation; in addition, it can be cultivated without heavy plows or pack animals.

The Diffusion of the City from Hearth Areas

The Diffusion of the City from Hearth Areas

Although urban life originated at several specific places in the world, cities are now found everywhere, including North America, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Australia. How did city life come to these regions? There are two possible explanations:

- Cities evolved spontaneously as native peoples created new technologies and social institutions.

- The preconditions for urban life are too specific for most cultures to have invented without contact with other urban areas; therefore, they must have learned these traits through contact with city dwellers. This scenario emphasizes the diffusion of ideas and techniques necessary for city life.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.8

In what part of the city would you say this monument is located? Can you think of examples from your own daily life of monumental architecture that symbolizes some ruling authority?

284

285

Diffusionists argue that the complicated array of ideas and techniques that gave rise to the first cities in Mesopotamia was shared with other people in both the Nile and the Indus River valleys who were on the verge of urban transformation. Indeed, archaeological evidence suggests that these three civilizations had trade ties with one another. Soapstone objects manufactured in Tepe Yahya, 500 miles (800 kilometers) to the east of Mesopotamia, have been uncovered in the ruins of both Mesopotamian and Indus River valley cities, which are separated by thousands of miles. Writings of the Indus civilization have also been found in Mesopotamian urban sites. Although diffusionists use this artifactual evidence to argue that the idea of the city spread from hearth to hearth, an alternative view is that trading took place only after these cities were well established. There is also evidence of contact across the oceans between early urban dwellers of the New World and those of Asia and Africa, although it is unclear whether this means that urbanization diffused to Mesoamerica or simply that some trade routes existed between these peoples.

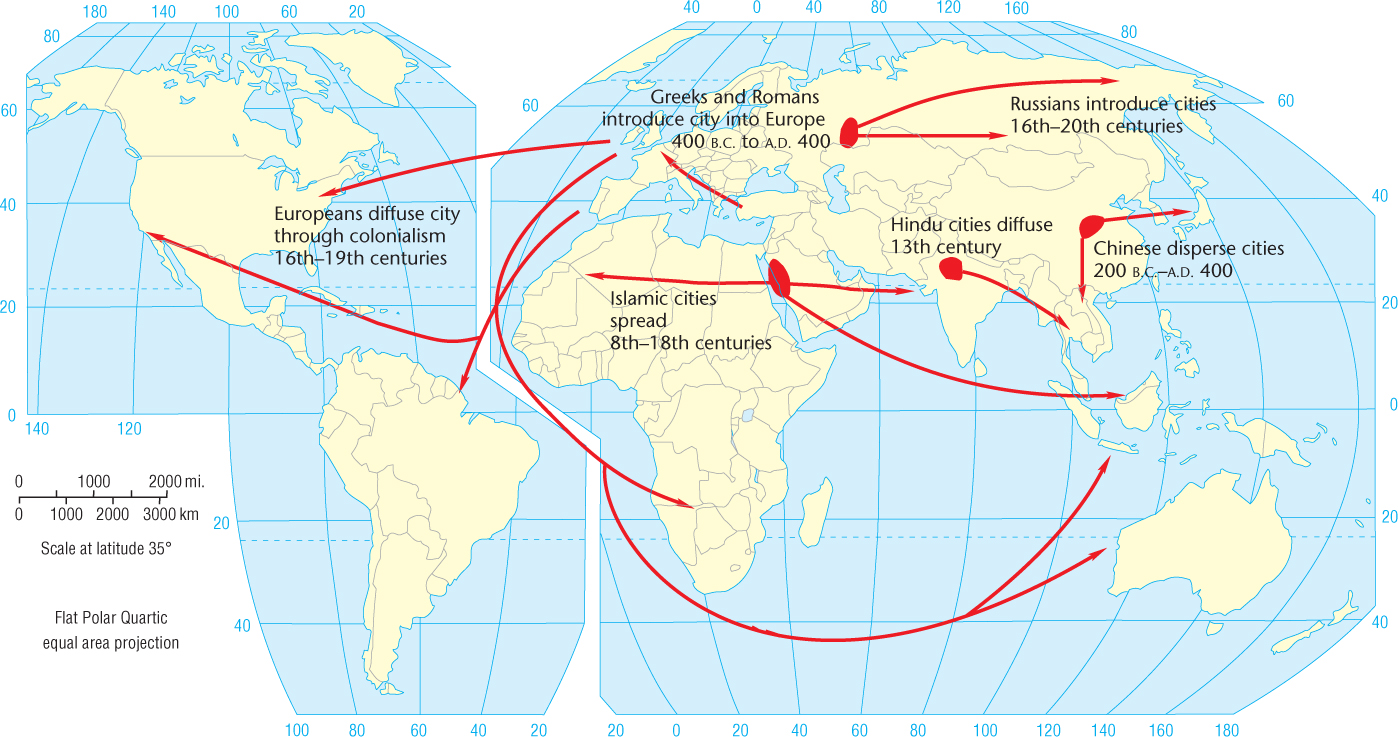

Nonetheless, there is little doubt that diffusion has been responsible for the dispersal of the city in historical times (Figure 10.7), because the city has commonly been used as the vehicle for imperial expansion. Typically, urban life is carried outward in waves of conquest as the borders of an empire expand. Initially, the military controls newly won lands and sets up collection points for local resources, which are then shipped back into the heart of the empire. As the surrounding countryside is increasingly pacified, the new collection points lose some of their military atmosphere and begin to show the social diversity of a city. Artisans, merchants, and bureaucrats increase in number; families appear; the native people are slowly assimilated into the settlement as workers and may eventually control the city. Finally, the process repeats itself as the empire pushes farther outward.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.9

What does this map tell us about the importance of urban life to military conquest?

This process, however, did not always proceed without opposition. The imposition of a foreign civilization on native peoples was often met with resistance, both physical and symbolic. Expanding urban centers relied on the surrounding countryside for support. Their food was supplied by farmers living fairly close to the city walls, and tribute was exacted from the agricultural peoples living on the edges of the urban world. The increasing needs of the city required more and more land from which to draw resources. However, the peasants farming that land may not have wanted to change their way of life to accommodate the city. The fierce resistance of many Native American groups to the spread of Western urbanization is testimony to the potential power of folk society to defy urbanization, although the destructive long-term effects of such resistance suggest that the organized military efforts of urban society were difficult to overcome.

286

Rural-to-Urban Migration

Rural-to-Urban Migration

This analysis of the diffusion of cities throughout the world helps us explain historically the increase in urban population, since it went hand-in-hand with the growing number of cities. In today’s world, however, increasing urbanization is caused by two related phenomena: natural population increase (see Chapter 3) and rural-to-urban migrations. While the United Nations estimates that natural increase accounts for the majority of the recent growth in urban population, it was rural-to-urban migrations of the past 20 to 30 years that brought millions of people originally into urban life. In countries throughout Africa and Asia, large numbers of people have left their rural villages and migrated to cities for better economic and social opportunities. Although people flock to the cities in search of jobs, there is often not a perfect correlation between economic growth and urbanization. Cities increase in size not necessarily because there are jobs to lure workers but rather because conditions in the countryside are much worse. In India, for example, rural poverty has exacerbated the rapid population increase in such cities as Mumbai (formerly Bombay) and Kolkata (formerly Calcutta). People leave the countryside in the hope that urban life will offer a slight improvement, and often it does. Given the new global economy, however, many of the jobs that are available in these cities are low-skilled and low-paying manufacturing jobs with harsh working conditions. The result is that rural-to-urban migrants often find themselves either unemployed or with jobs that barely provide them a living.

Sociologist Alejandro Portes argues that the large internal migrations that bring impoverished agricultural people into the city are a phenomenon that can be traced back to colonial times. In colonial Latin America, for example, the city was essentially home to the Spanish elite. When preconquest agricultural patterns were disrupted, peasants came to the city looking to improve their economic situation. These people usually lived on the margins of the city. Moreover, they were completely disenfranchised because only landowners had the right to hold office. The reaction by the elite to this ongoing pattern of movement of large masses of people into the city was a mixture of tolerance and indifference, with no one taking responsibility to integrate the migrants into the city.

China presents a particularly interesting example of rural-to-urban migration. Until the late 1970s, the country was predominantly rural, but state economic policies thereafter encouraged industrialization, and most of those industries were located in urban areas along its southeastern coast. The state lifted its restrictions on internal migration, which enabled its rural population to become more mobile. Today it is estimated that 18 million Chinese migrate to cities each year, a phenomenal rate of urban increase. These migrations are drastically altering the economy, society, and culture of China, as the country experiences this unprecedented shift from a rural, agricultural nation to one based on cities and industry.

The Globalization of Cities

The Globalization of Cities

Many of the globalizing forces we have already discussed in this book—the integration of international economies, the merging of different cultures, and the reshaping of social organization—are centered in urban life. In other words, cities are the places where one can see both the multitude of benefits that come from globalization and the numerous pitfalls that it can bring. In this way, all cities can be considered global cities, places being shaped by the new global forces of diffusion. However, scholars have identified two particular types of cities that are key to understanding globalization.

global city A city that is a control center of the global economy.

Global cities are those that have become the control centers of the global economy—the places where major decisions about the world’s commercial networks and financial markets are made. These cities house a concentration of multinational and transnational corporate headquarters, international financial services, media offices, and related economic and cultural services. According to sociologist Saskia Sassen, there are only three such cities now operating at this level: New York City, London, and Tokyo. These cities have become, in many ways, the headquarters for a global economy and form the top level of a hierarchical global system of cities.

More recently, scholars have begun to broaden their analysis of global cities in order to also understand the next tier of cities within the urban hierarchy—those that contain a large percentage of international producer service firms (law, accountancy, advertising, financial, consultancy). In this new analysis, cities are categorized by the number and type of transnational firms they house—not only headquarters, but regional and national offices as well. This analysis has identified globally and regionally dominant cities and cities that are major participants in the new global economy. Geographers Yefang Huang, Yee Leung, and Jianfa Shen refer to these as international cities—places that are significant because they are centers of the new international economy. The result is a very interesting list organized into classes of international cities, dominated by six in class A (London, New York, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Singapore, and Paris), followed by 10 in class B and 44 in class C. Figure 10.8 maps those cities by class, revealing the dominance of certain regions within the global economy (the United States, Europe, parts of Asia) and revealing another level within the global system of cities.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.10

Look carefully at the distribution of these cities, and see if you can explain their locations by considering their national and regional contexts.

287

globalizing city A city being shaped by the new global economy and culture.

A globalizing city is one that is being shaped by the new global economy and culture. This includes just about every city, present and past, to one degree or another. As geographer Brenda Yeoh indicates, cities have almost always been important hubs of activity beyond the national scale, and therefore it is not surprising that they figure prominently in contemporary discussions of globalization. The degree of globalization in the past 30 years has sharpened and enhanced the ways in which global economies and cultures shape cities. As geographer Kris Olds points out, there are five interrelated dimensions of current globalizing processes that are shaping our cities: the development of an international financial system, the globalization of property markets, the prominence of transnational corporations, the stretching and intensifying of social and cultural networks, and the increased degree of international travel and networking.

Not all cities are affected by these globalizing processes in the same way. Some cities, like London, are the control centers of the world economy, while others, like Jakarta, provide sites of production for the global economy. The differences between these two types of cities emerge out of cultural uniqueness and historical circumstance, particularly the colonial relationships that developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. With the end of colonialism and the movement toward political and economic independence, developing countries entered a period of rapid, sometimes tumultuous change. Cities have often been the focal point of this change, and as we have seen, millions of people have migrated to cities in search of a better life. Some of these newly globalizing cities are moving into the ranks of international cities, as you can see by looking at Figure 10.8. Other globalizing cities like Gabarone in Botswana are just now beginning to feel the impacts of population growth and global economic integration.