The Ecology of Urban Location

The Ecology of Urban Location

What is the relationship between cities and their physical settings? At first glance, cities seem totally divorced from the natural environment. What possible relationships could the shiny glass office buildings, paved streets, and high-rise apartment buildings that characterize most cities have with forests, fields, and rivers? In this section we examine several different ways to think about the relationships between urban life and its natural setting.

288

Site and Situation

Site and Situation

site The local setting of a city.

situation The regional setting of a city.

There are two components of urban location: site and situation. Site refers to the local setting of a city; the situation is the regional setting or location. As an example of site and situation, consider San Francisco. The original site of the Mexican settlement that became San Francisco was on a shallow cove on the eastern (inland) shore of a peninsula. The importance of its situation was that it drew on waterborne traffic coming across the bay from other, smaller settlements. Hence the town could act as a transshipment point.

Both site and situation are dynamic, changing over time. For example, in San Francisco during the gold rush period of the 1850s, the small cove was filled to create flatland for warehouses and to facilitate extending wharves into deeper bay waters. The filled-in cove is now occupied by the heart of the central business district (Figure 10.9). The geographical situation also changed as patterns of trade and transportation technology evolved. The original transbay situation was quickly replaced during the gold rush by a new role: supplying the mines and settlements of the gold country. Access to the two major rivers leading to the mines, plus continued ties to ocean trade routes, became important components of the city’s situation.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.11

What hazard would such fill land create?

San Francisco’s situation has changed dramatically in the past two decades, for it is no longer the major port of the bay. The change in technology to containerized cargo was adopted more quickly by Oakland, the rival city on the opposite side of the bay, and San Francisco declined as a port city. Oakland was able to accommodate containerized cargo in part because it filled in huge tracts of shallow bay lands, creating a massive area for the loading, unloading, and storage of cargo containers.

289

Certain attributes of the physical environment have been important in the location of cities. Those cities with distinct functions, such as defense or trade, were located because of specific physical characteristics. The locations of many contemporary cities can be partially explained by decisions made in the past that capitalized on the advantages of certain sites. The following classifications detail some of the different location possibilities.

Defensive Sites

defensive site A location from which a city can be easily protected from invaders.

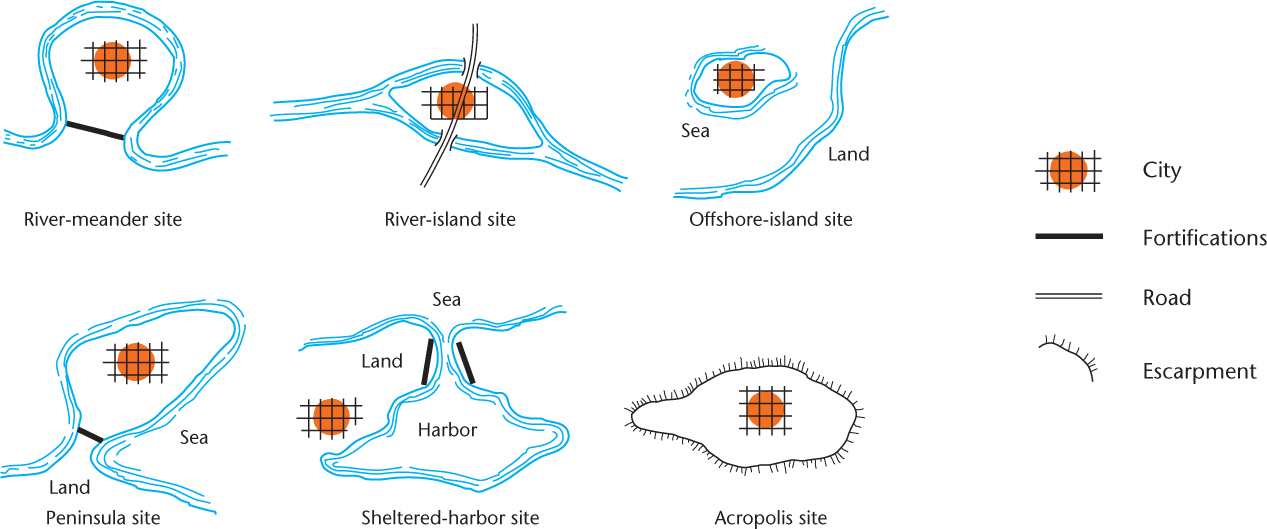

Defensive Sites There are many types of defensive sites for cities (some are diagrammed in Figure 10.10). A defensive site is a location that can be easily protected from invaders. The rivermeander site, with the city located inside a loop where the stream turns back on itself, leaves only a narrow neck of land unprotected by water. Cities such as Bern, Switzerland, and New Orleans are situated inside river meanders. Indeed, the nickname for New Orleans, Crescent City, refers to the curve of the Mississippi River.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.12

What challenges result for cities established on defensible sites?

Even more advantageous was the river-island site, which, because the stream was split into two parts, often combined a natural moat with an easy river crossing. For example, Montreal is situated on a large island surrounded by the St. Lawrence River and other water channels. The offshore-island site—that is, islands lying off the seashore or in lakes—offered similar defensive advantages (Figure 10.11). Mexico City began as an Indian settlement on a lake island. Venice is the classic example of a city built on offshore islands in the sea, as is Hong Kong. Peninsula sites were almost as advantageous as island sites, because they offered natural water defenses on all but one side. Boston was founded on a peninsula for this reason, and a wooden palisade wall was built across the neck of the peninsula.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.13

Why would a defensible site have been important when the abbey was established in the Middle Ages?

290

Danger of attack from the sea often prompted sheltered-harbor defensive sites, where a narrow entrance to the harbor could be defended easily. Examples of sheltered-harbor sites include Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, and San Francisco.

High points were also sought out. These are often referred to as acropolis sites; the word acropolis means “high city.” Originally the city developed around a fortification on the high ground and then spilled out over the surrounding lowland. Athens is the prototype of acropolis sites, but many other cities are similarly located.

Trade-Route Sites

trade-route site A place for a city at a significant point on a transportation route.

Trade-Route Sites Defense was not always the primary consideration. Sometimes, urban centers were built on trade-route sites—that is, at important points along already established trade routes. Here, too, the influence of the physical environment can be detected.

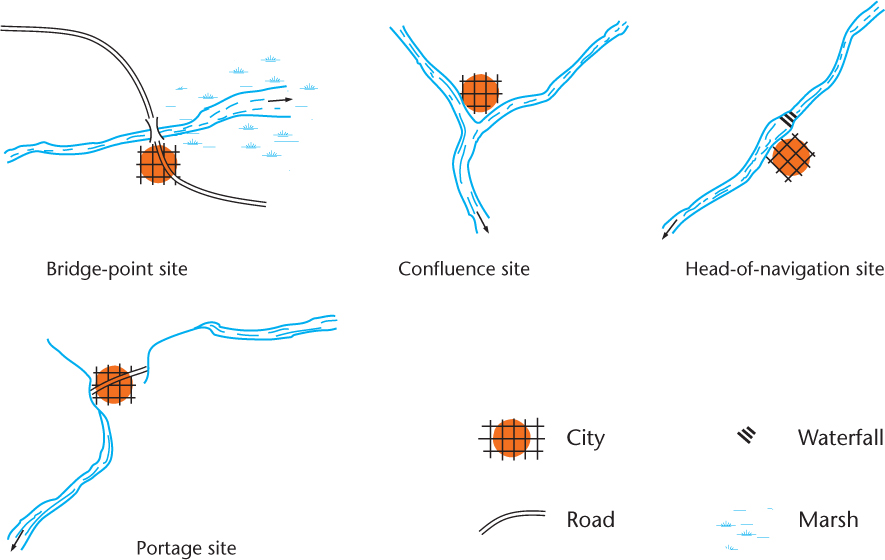

Especially common types of trade-route sites (Figure 10.12) are bridge-point sites and river-ford sites, places where major land routes could easily cross over rivers. Typically, these were sites where streams were narrow and shallow with firm banks. Occasionally, such cities even bear in their names the evidence of their sites, as in Frankfurt (“ford of the Franks”), Germany, and Oxford, England. The site for London was chosen because it is the lowest point on the Thames River where a bridge—the famous London Bridge—could easily be built to serve a trade route running inland from Dover on the sea.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.14

Is your city or one near you located on a trade-route site?

Confluence sites are also common. They allow cities to be situated at the point where two navigable streams flow together. Pittsburgh, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, is a fine example (Figure 10.13). Head-of-navigation sites, where navigable water routes begin, are even more common, because goods must be transshipped at such points. Iquitos, Peru, is located at the head-of-navigation site for the Amazon River, and Minneapolis–St. Paul, at the falls of the Mississippi River, also occupies a head-of-navigation site. Portage sites are very similar. Here, goods were portaged from one river to another. (Portage means the act of carrying a ship and/or its cargo between navigable waters.) Chicago is near a short portage between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River drainage basin. In these ways and others, an urban site can be influenced by the physical environment. But so, too, do cities change that physical environment in a multitude of ways.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.15

Before the American Revolution, Pittsburgh was the site of a fort. Why was it a defensible site as well as being a trade-route site?

Natural Disasters

Natural Disasters

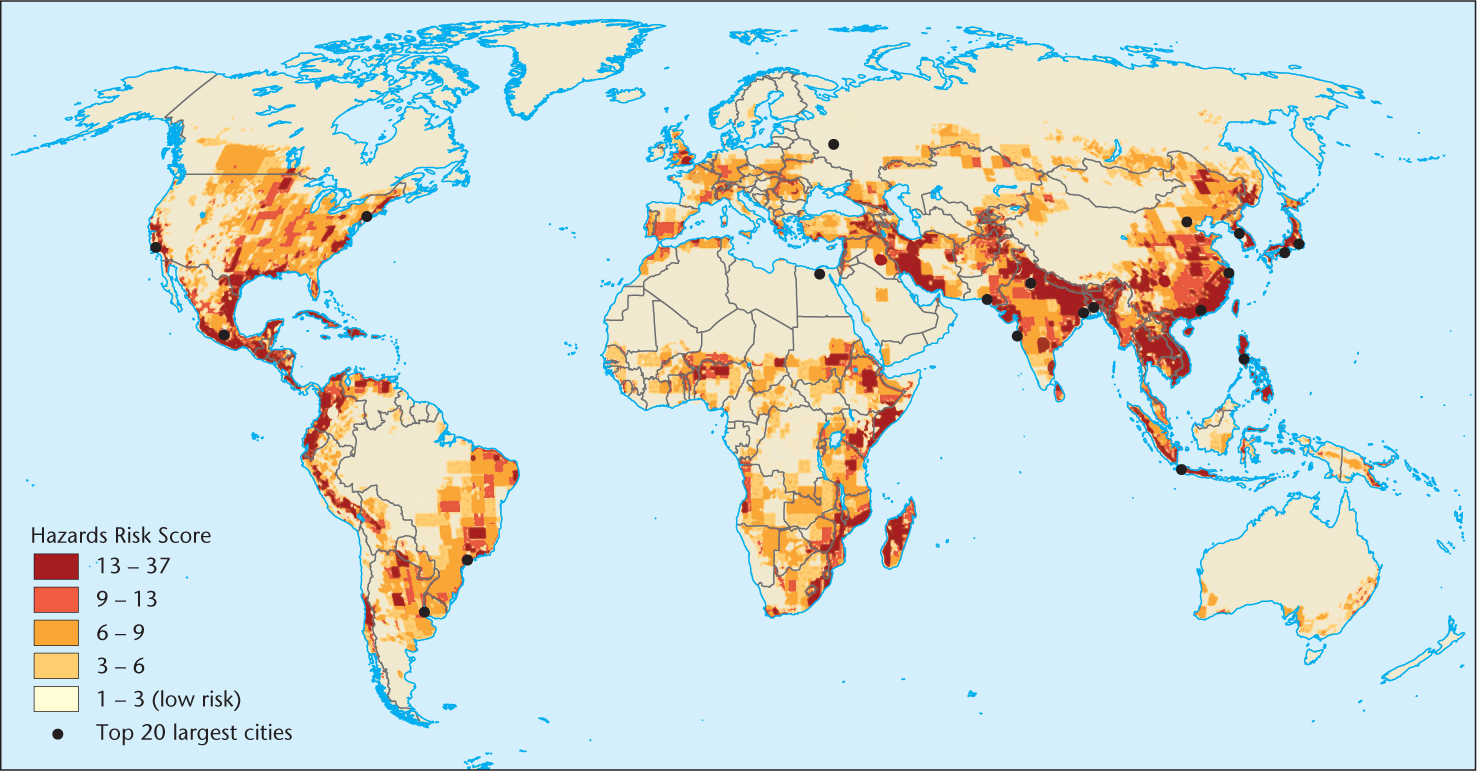

Catastrophic events over the past decade, including tsunamis in Indonesia and Japan, widespread flooding in Europe and Africa, and frequent wildfires in the U.S. Southwest, have become critical reminders of the vulnerability of human settlements to natural disasters. This vulnerability was graphically depicted in photos taken in the aftermath of a major earthquake in the Caribbean island nation of Haiti in January 2010. This disaster killed at least 300,000 people, injured hundreds of thousands, and displaced more than 1 million residents. Densely populated urban areas like the Haitian capital city of Port-au-Prince, with their concentrations of people, are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters because so many peoples’ lives and livelihoods are at risk.

In addition, many cities around the world are situated near water, so they are often located in the direct paths of multiple types of disasters, including hurricanes and tsunamis (which are often caused by earthquakes). Making matters even worse, some scientists have recently noted an increase in the occurrence of natural disasters. They attribute this increase partly to global climate change brought about by a range of human activities including deforestation, increasing industrialization, and harmful agricultural practices.

The combination of increasing urbanization and a growing number of natural disasters means that more and more people’s lives are being impacted adversely. According to the United Nations Environment Program, since the start of the new millennium, billions of people around the world have been affected by some 2,500 natural disasters (Figure 10.14). As with the Haitian earthquake, it is often poor people who are the most affected, since they tend to live in structures that are not well built and in sections of the city that are particularly vulnerable to environmental forces. In fact, in many cities in the developing world, squatter settlements populated by the poor are often situated on steep hillsides or in poorly drained low-lying areas that are highly prone to flooding, mudslides, and other disasters.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.16

Why do people build cities in such vulnerable locations?

291

292

Urbanization and Sustainability

Urbanization and Sustainability

urban footprint The total impact of urban areas on the natural environment.

As we saw in Chapter 9, industrialization goes hand in hand with urbanization, so the environmental impacts of industrialization are often found in cities. But urbanization generates its own set of environmental impacts: supplying enough energy, food, and water to large concentrations of people puts an array of stresses on the natural environment. Scholars now refer to these varied impacts of urban areas on the environment as the urban footprint. For example, Las Vegas is one of the fastest-growing urban areas in the United States, yet it is located in a desert (Figure 10.15). The city’s primary water source is the Colorado River, but the costs of delivering that water are extremely high. It is expensive to construct the dams and infrastructure necessary to move the water into the city, and the environmental damage to the region is severe. The dams alter the flows of water through the Colorado Valley, harming fish and disrupting aquatic life cycles, and the energy required to divert the water to the city leads to higher sulfur dioxide emissions, which have been shown to contribute to global warming.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.17

Why do you think the founders of Las Vegas would choose to locate the city in the middle of a desert?

But the environmental effects of increased urbanization—the urban footprint—can spread beyond the immediate stresses caused by higher concentrations of population. Urban living often leads to rising levels of consumption, as new urbanites gain access to better jobs and more disposable income. This growing demand for things like better food can impact areas far from urban centers. For example, as the United Nations report Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth suggests, tropical forests in Tobasco, an area 400 miles away from Mexico City, have been turned into cattle-grazing areas in response to urbanites’ demands for meat, while, in a second example, a major contributing factor to the deforestation of the Amazon is the increased demand for soybeans from the newly urbanizing regions of China as well as from the urbanites of the United States, Japan, and Europe.

293

Urbanization, however, does not necessarily imply environmental degradation. For example, the higher densities of population that cities represent can be seen as a form of sustainable growth. Half the population of the world—the urban half—lives on approximately 3 percent of the landmass. The concentration of people in cities therefore opens up other areas that can be protected and left relatively free from human use. Many countries in the developing and developed world are working on local and regional planning projects that on the one hand maintain urban boundaries and prevent sprawl and on the other hand protect natural environments outside urban areas from environmental degradation. Such urban environmental conservation projects will likely become increasingly important in future years.