Cultural Interaction in Urban Geography

Cultural Interaction in Urban Geography

central-place theory A set of models designed to explain the spatial distribution of urban service centers.

How can we understand the location of cities as an integrated system? In recent decades, urban geographers have studied the spatial distribution of towns and cities to determine some of the economic and political factors that influence the pattern of cities. In doing so, they have created a number of models that collectively make up central-place theory. These models represent examples of cultural interaction.

Central-Place Theory

Central-Place Theory

central place A town or city engaged primarily in the service stages of production; a regional center.

Most urban centers are engaged mainly in the service industries. The service activities of urban centers include transportation, communication, and utilities—services that facilitate the movement of goods and that provide networks for the exchange of ideas about those goods (see Chapter 9 for a more detailed examination of these different industrial activities). Towns and cities that support such activities are called central places.

threshold In central-place theory, the size of the population required to make provision of goods and services economically feasible.

range In central-place theory, the average maximum distance people will travel to purchase a good or service.

In the early 1930s, the German geographer Walter Christaller first formulated central-place theory as a series of models designed to explain the spatial distribution of urban centers. Crucial to his theory is the fact that different goods and services vary both in threshold, the size of the population required to make provision of the good or service economically feasible, and in range, the average maximum distance people will travel to purchase a good or service. For example, a larger number of people are required to support a hospital, university, or department store than to support a gasoline station, post office, or grocery store. Similarly, consumers are willing to travel a greater distance to consult a heart specialist or purchase an automobile than to buy a loaf of bread or visit a movie theater.

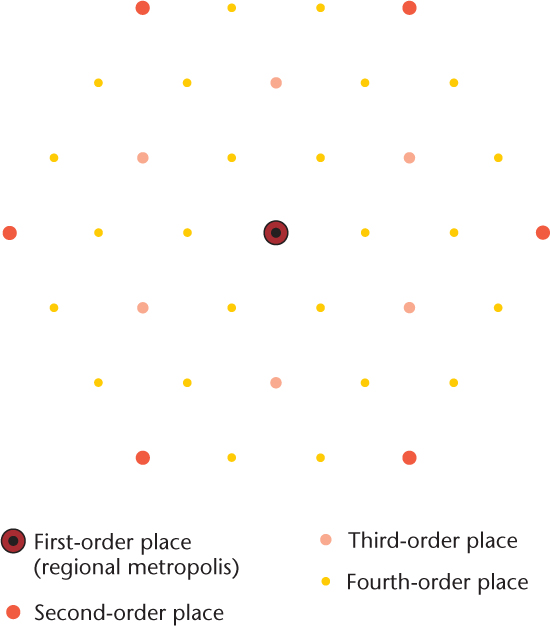

Because the range of central goods and services varies, urban centers are arranged in an orderly hierarchy. Some central places are small and offer a limited variety of services and goods; others are large and offer an abundance. At the top of this hierarchy are regional metropolises—cities such as New York, Beijing, or Mumbai—that offer all services associated with central places and that have very large tributary trade areas, or hinterlands. At the opposite extreme are small market villages and roadside hamlets, which may contain nothing more than a post office, service station, or café. Between these two extremes are central places of various degrees of importance. One regional metropolis may contain thousands of smaller central places in its tributary market area (Figure 10.16).

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.18

In what kind of terrain would this arrangement be most likely?

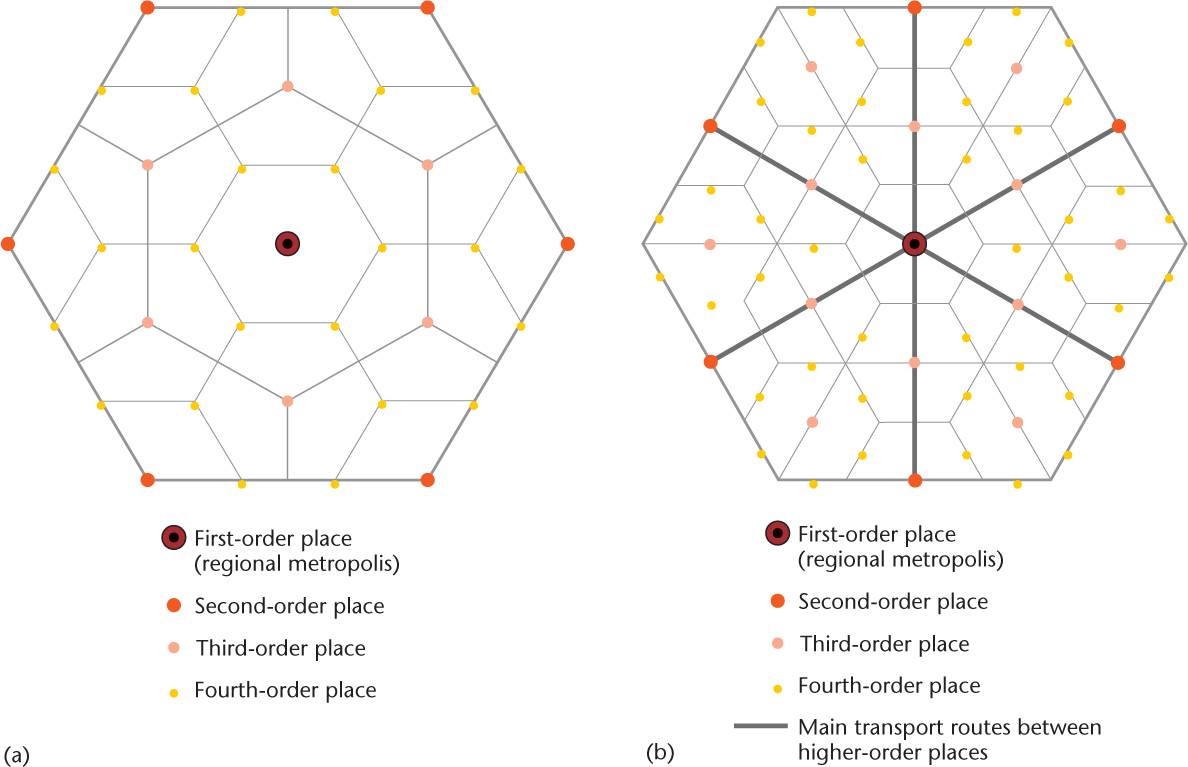

With this hierarchy as a background, Christaller evaluated the individual influence of three forces (the market, transportation, and political borders) in determining the spacing and distribution of urban centers by creating models. His first model measured the influence of the market and range of goods on the spacing of cities. To simplify the model, he assumed that the terrain, soils, and other environmental factors were uniform; that transportation was universally available; and that all regions would be supplied with goods and services from the minimum number of central places. If market and range of goods were the only causal forces, the distribution of towns and cities would produce a pattern of nested hexagons, each with a central place at its center (Figure 10.17a).

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.19

Why, in this model, would a hexagon be the shape to appear instead of a square, circle, or some other shape?

294

hinterland The area surrounding a city and influenced by it.

In Christaller’s second model, he measured the influence of transportation on the spacing of central places. He no longer assumed that transportation was universally and equally available in the hinterland. Instead, he assumed that as many demands for transport as possible would be met with the minimum expenditure for construction and maintenance of transportation facilities. Thus, as many high-ranking central places as possible would be on straightline routes between the primary central places (Figure 10.17). When transportation is considered to be the influential factor in shaping the spacing of central places, the pattern is rather different from that created by the market factor. This transportation-driven pattern occurs because direct routes between adjacent regional metropolises do not pass through central places of the next-lowest rank. As a result, these second-rank central places are pulled from the corners of the hexagonal market area to the midpoints in order to be on the straight-line routes between adjacent regional metropolises.

Christaller hypothesized that the market factor would be the greater force in rural countries, where goods were seldom shipped throughout a region. In densely settled industrialized countries, however, he believed that the transportation factor would be stronger because there were greater numbers of central places and more demand for long-distance transportation.

Christaller devised a third model to measure the effect of political borders on the distribution of central places. He recognized that political boundaries, especially within independent countries, would tend to follow the hexagonal market-area limits of each central place that was a political center. He also recognized that such borders tend to separate people and retard the movement of goods and services. Such borders necessarily cut through the market areas of many central places below the rank of regional metropolis. Central places in such border regions lose rank and size because their market areas are politically cut in two. Border towns are thus stunted, and important central places are pushed away from the border, which distorts the hexagonal pattern.

295

Market area, transportation, and political borders are but three of the many forces that influence the spatial distribution of central places. For example, in all three of these models, it is assumed that the physical environment is uniform and that people are evenly distributed. Of course, neither of these is true, leading to some distortions in the model. Nonetheless, central-place theory has proven to be a very useful tool for understanding the locations of cities and services in relationship to population. For example, with increasing concerns about environmental sustainability, regional planners have begun to use central-place theory to think about how to minimize transportation costs in a particular region by siting key services in central locations. Yet it is important to keep in mind that the model fails to take into account such cultural factors as people’s historical attachment to places. For example, if people have shopped in a certain city for several generations, or even several years, and feel attached to that place, it is often the case that they choose not to shop elsewhere, even if another city is located closer to them. In other words, the most economically rational (in terms of saving money by traveling less) path is not always the one most preferred by people.

Reflecting on Geography

Question 10.20

If Christaller’s assumptions did not hold, in what ways would central-place theory have to be altered?