Urban Cultural Landscapes

Urban Cultural Landscapes

As you probably already know from your travels, the look of cities varies from place to place. Some cities have bustling downtowns where most of the residents work, while others are characterized by nodes of activities clustered on the suburban fringe; some cities are built around a set of historical buildings with political or religious significance, while the centers of other cities are dominated by new skyscrapers housing financial offices. Finally, some cities have streets laid out in a gridlike pattern, while in other cities streets are a crisscrossed jumble without apparent order. How can we make sense of this range of urban landscapes?

Globalizing Cities in the Developing World

Globalizing Cities in the Developing World

squatter settlement or barriada An illegal housing settlement, usually made up of temporary shelters, that surrounds a large city and may eventually become a permanent part of the city.

In cities of the developing world, the combination of large numbers of migrants and widespread unemployment leads to overwhelming pressure for low-rent housing. Governments have rarely been able to meet these needs through housing projects, so one of the most characteristic landscape features of cities in the developing world has been the construction of illegal housing usually made up of temporary shelters: squatter settlements. Squatter settlements, or barriadas (Figure 10.18 are often referred to as slums—areas of degraded housing. The United Nations defines a slum household as a cohabiting group that lacks one or more of the following conditions: an adequate physical structure that protects people from extreme climatic conditions, sufficient living area such that no more than three people share a room, access to a sufficient amount of water, access to sanitation, and secure tenure or protection from forced eviction. Current estimates suggest that more than 1 billion people in the world live in slums. In greater Cairo alone, for example, it is estimated that 5.5 million people live in slum conditions in squatter settlements. In Manila, it is estimated that almost half of the city’s 19 million inhabitants live in slum conditions in squatter settlements.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.21

What upgrading is evident in the Mexico City settlement?

Squatter settlements usually begin as collections of crude shacks constructed from scrap materials; gradually, they become increasingly elaborate and permanent. Paths and walkways link houses, vegetable gardens spring up, and often water and electricity are bootlegged into the area so that a common tap or outlet serves a number of houses. At later stages, such economic pursuits as handicrafts and small-scale artisan activities take place in the squatter settlements. In many instances, these supposedly temporary settlements become permanent parts of the city and function as many neighborhoods do—that is, as social, economic, and cultural centers.

extended metropolitan region (EMR) A new type of urban region, complex in both landscape form and function, created by the rapid spatial expansion of a city in the developing world.

Squatter settlements are located not only in downtown areas but also close to places where people work. In many cities, this means places that just a few years ago were considered rural. Because of growing populations and pressures on space, many globalizing cities in the developing world are expanding outward. Some of these cities, such as Mexico City, Hanoi, and Manila, are expanding so rapidly into the countryside that the city is swallowing up smaller villages and rural areas. In this way, these new urban forms are blurring the distinction between the rural and the urban, creating what some scholars have called extended metropolitan regions (EMRs). Multinational corporations often rely on the labor of the new urban migrants, so the city grows rapidly at the margins as factories are built in export processing zones (EPZs; see Chapter 9). At the same time, the downtowns of these cities often experience not dispersal but concentration: highrises accommodate the regional offices of corporations and the services associated with them (media, advertising, personnel management, and so forth), and upper-class housing developments accommodate this new class of white-collar workers.

296

These new urban regions are complex in both landscape form and function because they developed rapidly, without any planning, and have in many cases incorporated preexisting places. Scholars who write about Mexico City, for example, find it impossible to speak of the city as one place; rather, they suggest that it can now only be represented as a pastiche of different places, each with its own center and outlying neighborhoods.

In addition, landscape forms associated with the global consumer, entertainment, and tourist economy are emerging in the new urban regions: American-style shopping districts (with American stores) and new airports, hotels, restaurants, and entertainment facilities. Many of these landscape developments are funded by international investments because entrepreneurs and governments in many parts of the world look to the new globalizing cities of the developing world as good places to make financial and real estate investments. Much of the extended metropolitan region of Hanoi, for example, was built with funds from a range of countries: an export processing zone and a golf and entertainment facility were partly funded by Malaysia; South Korea invested in a hotel, another golf course, and a business center; Taiwan was involved in a tourism project and an industrial park. Hanoi’s downtown is being developed with more hotels and office construction funded by Japan and Singapore. Finland provided the infrastructure for the water supply to one of these new developments.

Latin American Urban Landscapes

Latin American Urban Landscapes

To describe the landscapes of Latin American cities, urban geographers have developed a model, which is shown in Figure 1.17 (page 21), so you might want to refer to it as you read this section. In contrast to many contemporary cities in the United States, the central business districts of Latin American cities are vibrant, dynamic, and increasingly specialized. The dominance of the central district is explained partly by widespread reliance on public transit and partly by the existence of a large and relatively affluent population close to it. Outside the central district, the dominant component is a commercial spine surrounded by an elite residential sector. Because these two zones are interrelated, they are referred to as the spine/sector. This combination is an extension of the central business district down a major boulevard, along which the city’s important amenities, such as parks, theaters, restaurants, and even golf courses, are located. Strict zoning and land controls ensure continuation of these activities and protect the elite from incursions by low-income squatters.

Somewhat less prestigious is the inner-city zone of maturity, a collection of homes occupied by people unable to afford housing in the spine/sector. The zone of maturity is an area of upward mobility. The zone of accretion is a diverse collection of housing types, sizes, and quality, which can be thought of as a transition between the zone of maturity and the next zone. It is an area of ongoing construction and change, emblematic of the explosive population growth that characterizes the Latin American city. Although some neighborhoods within this zone have city-provided utilities, other blocks must rely on trucks to deliver essentials such as water and butane.

297

The most recent migrants to the Latin American city are found in the zone of peripheral squatter settlements. This fringe of poor people and inadequate housing contrasts dramatically with the affluent and comfortable suburbs that ring North American cities. Streets are unpaved, open trenches carry waste, residents haul water from distant locations, and electricity is often pirated by attaching illegal wires to the closest utility pole. Although this zone’s quality of life seems marginal, many residents transform these squatter settlements over time into permanent neighborhoods with minimal amenities.

Landscapes of the Apartheid and Postapartheid City

Landscapes of the Apartheid and Postapartheid City

apartheid In South Africa, a policy of racial segregation and discrimination against non-European groups.

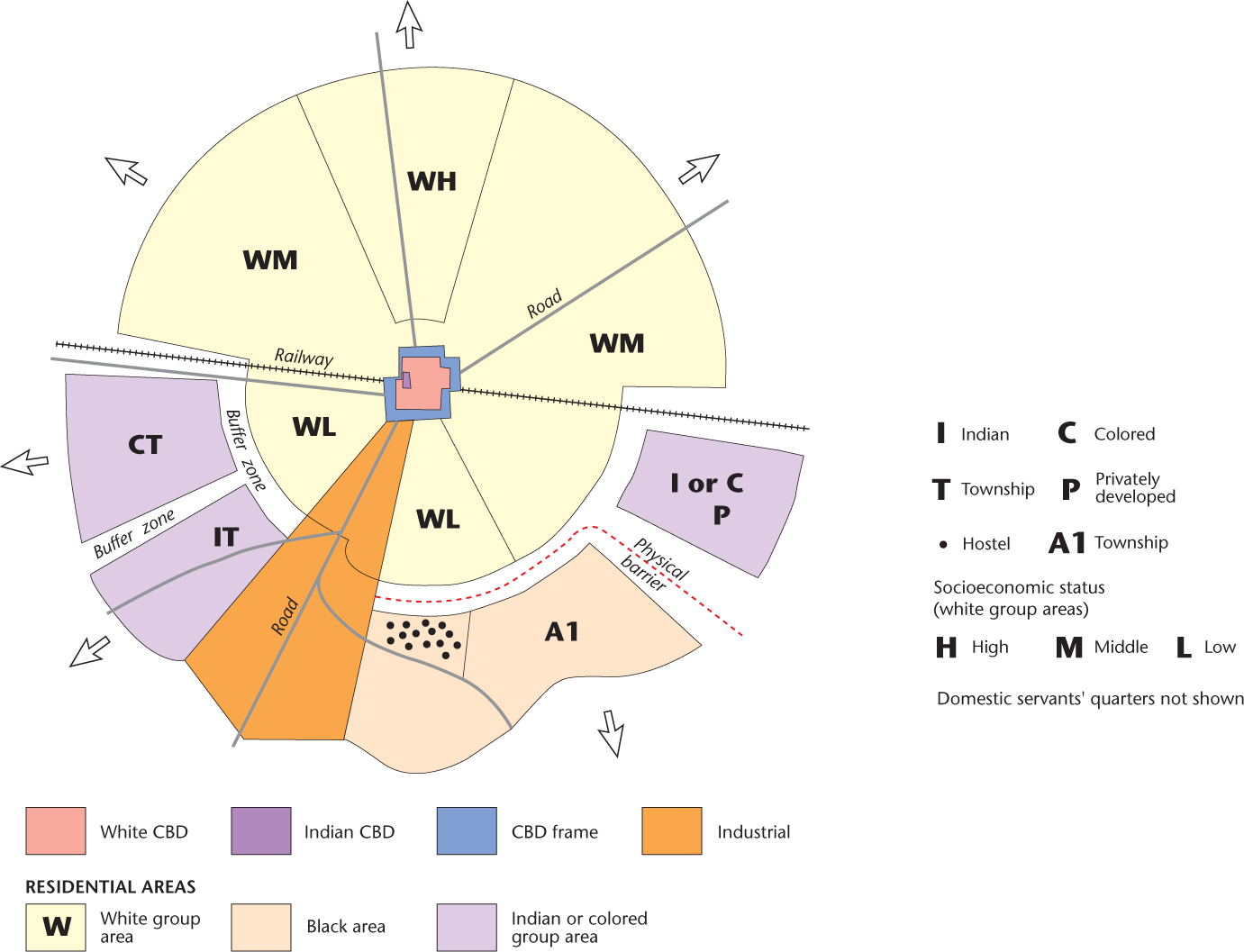

Racism and the residential segregation that often results from it can have profound effects on landscapes. In South Africa, the state-sanctioned policy of segregating “races,” known as apartheid, significantly altered urban patterns. Although racial segregation was not the only force shaping the apartheid city, it certainly was a dominant one. The intended effects of this policy on urban form are delineated in Figure 10.19. To understand this illustration fully, we need to outline some of the important components of the apartheid state.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.22

Why are nonwhite groups located close to industry?

The policies of economic and political discrimination against non-European groups in South Africa were formalized and sharpened under National Party rule after 1948. To segregate the “races,” the government passed two major pieces of legislation in 1950. The first was the Population Registration Act, which mandated the classification of the population into discrete racial groups. The three major groups were white, black, and colored, each of which was subdivided into smaller categories. The second piece of major legislation was called the Group Areas Act. Its goal was, in the words of geographer A. J. Christopher, “to effect the total urban segregation of the various population groups defined under the Population Registration Act.” Cities were thus divided into sections that were to be inhabited only by members of one population group.

Although the effects of these acts on the form of South African cities did not appear overnight, they were massive nonetheless. Members of nonwhite groups were by far the ones most adversely affected. Almost without exception, the downtowns of cities were restricted to whites, whereas those areas set aside for nonwhites were peripheral and restricted, often lacking any urban services, such as transportation and shopping. Large numbers of nonwhite families were displaced with little or no compensation (estimates suggest that only 2 percent of the displaced families were white). Buffer zones were established between residential areas to curtail contact between groups, further hindering access to the central city for those groups pushed into the periphery.

298

After the change of government in 1994, apartheid came to an end as an official policy, and the laws that enforced racial segregation in South Africa were abolished. Results from the 1996 census revealed a marked decline in degrees of racial segregation within South Africa’s cities, a trend that characterizes the postapartheid city. However, historical patterns of residential segregation and racial prejudice are very difficult to change. A. J. Christopher found that despite a general overall decline in levels of segregation, particularly among the colored population, the majority of the white population in South Africa remained isolated from their nonwhite neighbors, while the black population remained relatively isolated due to the lack of mobility caused by poverty.

Landscapes of the Socialist and Postsocialist City

Landscapes of the Socialist and Postsocialist City

The effects of centralized state policies on urban land-use patterns are also evident in the cities of the former Soviet Union and of other former socialist countries in eastern Europe. In the Soviet Union, for example, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 brought with it attempts by the state to confront and solve the urban problems brought by industrialization. Socialist principles called for the nationalization of all resources, including land. Further, central planning replaced market forces as the means for allocating those resources. These ideas had profound effects on the form of Soviet cities. The principles that underlie capitalist cities—that land is held privately and that the economic market dictates urban land use—were no longer the prime influences on urban form. Instead, Soviet policies attempted to create a more equitable arrangement of land uses in the city. The results of those policies included (1) a relative absence of residential segregation according to socioeconomic status, (2) equitable housing facilities for most citizens, (3) relatively equal accessibility to sites for the distribution of consumer items, (4) cultural amenities (theater, opera, and so on) located and priced to be accessible to as many people as possible, and (5) adequate and accessible public transportation. Although these results created better living and working conditions for many people, the situation was far from ideal. By the 1970s and 1980s, many Soviet citizens realized that their standards of living were well below those in the West and that the central planning system was not successful.

National policies of economic restructuring introduced in the late 1980s, referred to as perestroika, led to mandates to privatize resources and the land market. In the postsocialist city, market forces are once again dominant in shaping urban land uses, and the pace and scale of urban change are unprecedented. One of the most significant of those changes is the privatization of the housing market. In Moscow, for example, an increasing segment of the housing stock is in private hands, as opposed to being government owned. However, this privatization does not necessarily mean a better housing market for the city’s residents. In the past two decades, much new construction in Moscow has taken the form of high-priced residential and commercial properties. At the same time, rental prices in the city rose beyond affordable limits for many families. This combination of factors led to a collapse of the real estate market in Moscow, so today many newly constructed luxury buildings stand empty of tenants, while many other buildings were never completed at all. Meanwhile, many of Moscow’s residents continue to live in the communal apartments assigned to them under the Soviet system (Figure 10.20). In countries formerly part of or dominated by the Soviet Union, processes akin to gentrification (see Chapter 11) are taking place in the center of cities such as Prague, Czech Republic; Krakow, Poland; and Budapest, Hungary, displacing residents to the peripheral portions of the city while housing others in Western-style elegance.

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.23

What evidence of globalization does this photograph show?

299

Postsocialist cities are also taking on the look of Western cities. The downtowns are increasingly dominated by retailing outlets of familiar Western companies, such as Nike and McDonald’s. Tall office buildings that house financial service businesses are replacing industrial buildings. In other postsocialist cities, the new landscapes of finance capitalism are located outside the city center, where land is cheaper. In Prague, for example, most of the city center is of great historical significance and is therefore protected from new building construction. Large financial institutions (for example, international banks) have found locations farther out from the city to be ideal for the construction of modern office buildings that suit their needs. These new buildings are, in many cases, built to standards that make them more energy efficient and environmentally friendly than older historic buildings in the city center. These new financial centers bring with them economic growth, and some are now resembling the suburban sprawl of North American cities (Figure 10.21).

Thinking Geographically

Question 10.24

Compare this situation to the location of bank office buildings in North American cities.