Cultural Diffusion in the City

Cultural Diffusion in the City

centralizing force Diffusion force that encourages people or businesses to locate in the central city.

decentralizing force A diffusion force that encourages people or businesses to locate outside the central city. Also called suburbanizing force.

How can we understand the spatial movement of people and activities in the city? The patterns of activities we see in the city are the result of thousands of individual decisions about location: Where should we locate our store—in the central city or the suburbs? Where should we live—downtown or outside the city? And so on. The result of such decisions might be expansion at the city’s edge or the relocation of activities from one part of the city to another. The cultural geographer looks at such decisions in terms of expansion and relocation diffusion (see Chapter 1).

To understand the role of diffusion, let us divide the city into two major areas—the inner city and the outer city. Those diffusion forces that result in residences, stores, and factories locating in the inner or central city are centralizing forces. Those that result in activities locating outside the central city are called decentralizing forces, or suburbanizing forces. The pattern of homes, neighborhoods, offices, shops, and factories in the city results from the constant interplay of these two forces.

Centralization

Centralization

Centralization has two primary advantages: economic and social.

Economic Advantages

Economic Advantages An important economic advantage of central-city location has always been accessibility. For example, imagine that a department store seeks a new location. If its potential market area is viewed as a full circle, then naturally the best location is in the center. There, customers from all parts of the city can gain access with equal ease. Before the automobile, a central-city location was particularly important because public transportation—such as the streetcar—was usually focused there. A central location is also important to those who must deliver their goods to customers. Bakeries and dairies were usually located as close to the center of the city as possible to maximize the efficiency of their delivery routes.

Location near regional transportation facilities is another aspect of accessibility and is thus an economic advantage. Many a North American city developed with the railroad at its center. Hence, any activity that needed access to the railroad had to locate in the central city. In many urban areas, giant wholesale and retail manufacturing districts grew up around railroad districts, producing “freight-yard and terminal cities” that supplied the produce of the nation. Although many of these areas have been abandoned by their original occupants, a walk by the railroad tracks today will give the most casual pedestrian a view of the modern ruins of the railroad city.

306

agglomeration A snowballing geographical process by which secondary and service industrial activities become clustered in cities and compact industrial regions in order to share infrastructure and markets.

Another major economic advantage of the inner city is agglomeration, or clustering, which results in mutual benefits for businesses. Agglomeration is a snowballing geographical process by which secondary and service industrial activities become clustered in cities and compact industrial regions in order to share infrastructure and markets. For example, retail stores locate near one another to take advantage of the pedestrian traffic each generates. Because a large department store generates a good deal of foot traffic, any nearby store will benefit.

Historically, offices clustered in the central city because of their need for communication. Remember, the telephone was not invented until 1875. Before that, messengers hand-carried the work of banks, insurance firms, lawyers, and many other services. Clustering was essential for rapid communication. Even today, office buildings tend to cluster because face-to-face communication is still important for businesspeople. In addition, central offices take advantage of the complicated support system that grows up in a central city and aids everyday efficiency. Service providers such as printers, bars, restaurants, travel agents, and office suppliers are within easy reach.

Social Advantages

Social Advantages Three social factors have traditionally reinforced central-city location: historical momentum, prestige, and the need to locate near work. The strength of historical momentum should not be underestimated. Many activities remain in the central city simply because they began there long ago. For example, the financial district in San Francisco is located mainly on Montgomery Street. This street originally lay along the waterfront, and San Francisco’s first financial institutions were established there in the mid-nineteenth century because it was the center of commercial action. In later years, however, landfill extended the shoreline (see Figure 10.9). Today, the financial district is several blocks from the bay; consequently, the district that began at the wharf head remained at its original location, even though other activity moved with the changing shoreline.

The prestige associated with the downtown area is also a strong centralizing force. Some activities still necessitate a central-city address. Think how important it is for some advertising firms to be on New York’s Madison Avenue or for a stockbroker to be on Wall Street. This factor extends to many activities in cities of all sizes. The “downtown lawyer” and the “uptown banker” are examples.

Residences have often been located in the central city because of the prestige associated with it. For example, in Chicago, the Magnificent Mile along the north end of Michigan Avenue has long attracted affluent residents desiring a prestigious address. Here, luxury high-rise apartments with stunning lake views are interspersed with high-end retail stores and restaurants, elite law firms and advertising agencies, and major television and media firms (Figure 11.6). Many cities around the world feature similarly prestigious districts in downtown areas. The Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris, Severn Road in Hong Kong, and Ostozhenka Street in Moscow all offer residents the opportunity to live in some of the most expensive and exclusive downtown properties in the world.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.8

Why do you think that prestigious addresses in many downtown areas have retained their elite status despite the increasing movement of affluent people to suburban areas around the world?

307

Probably the strongest social force for centralization has been the desire to live near one’s place of employment. Until the development of the electric trolley in the 1880s, most urban dwellers had little alternative but to walk to work, and as most employment was in the central city, people had no choice but to live nearby. Upper-income people had their carriages and cabs, but others had nothing. Even after the introduction of electric streetcar lines in the 1880s, which made possible the exodus of some middle-class residents, many people continued to walk to work, particularly those who could not afford the new housing being constructed in what Sam Bass Warner has called “streetcar suburbs.”

Suburbanization and Decentralization

Suburbanization and Decentralization

uneven development The tendency for industry to develop in a coreperiphery pattern, enriching the industrialized countries of the core and impoverishing the less industrialized periphery. This term is also used to describe urban patterns in which suburban areas are enriched while the inner city is impoverished.

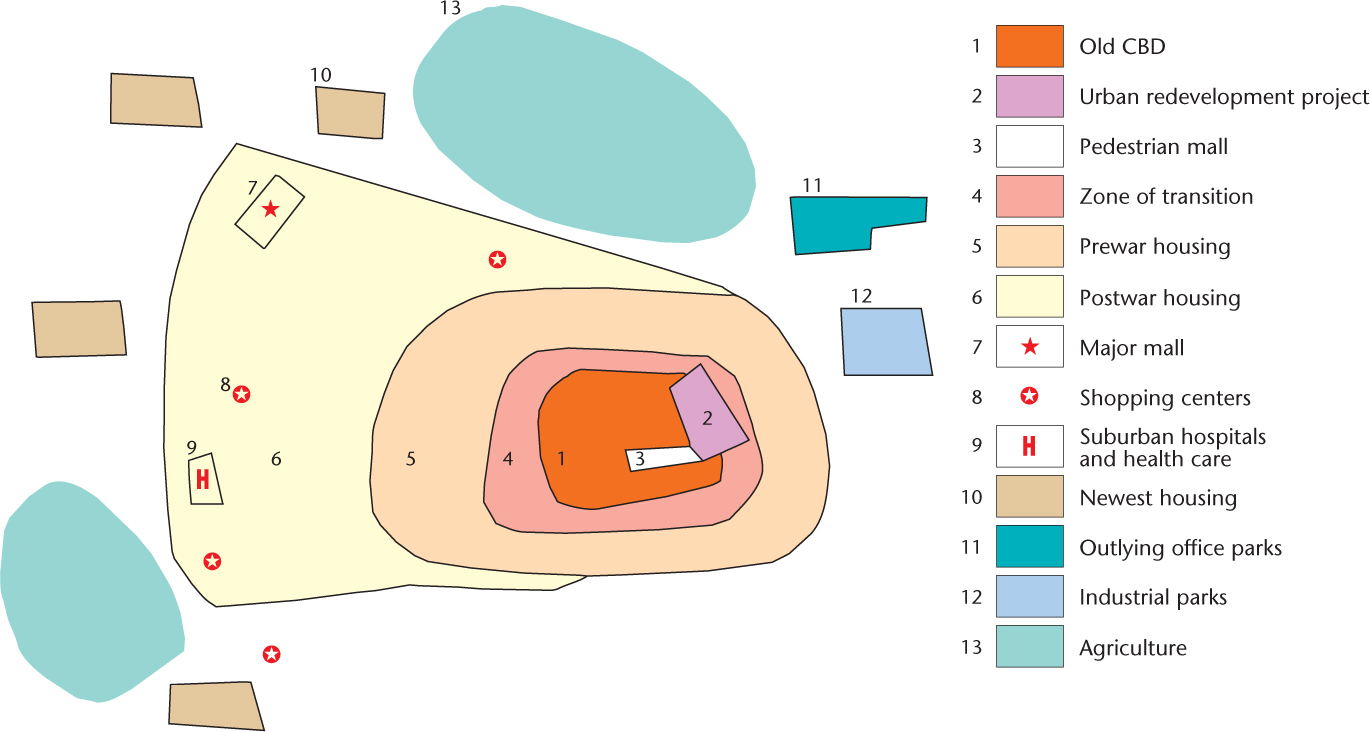

The past 50 years have witnessed massive changes in the form and function of most Western cities (Figure 11.7). In the United States in particular, the suburbanization of residences and the decentralization of workplaces have emptied many downtowns of economic vitality. How and why has this happened? Geographer Neil Smith argues that the processes of suburbanization and decline of the inner city are fundamentally linked: capital investment in the suburbs is often made possible by disinvestment, or the removal of money, from the central city. In the post–World War II United States, investors found greater returns on their money in the new suburbs than they did in the inner city, and therefore much of the economic boom of this period took place in the suburbs at the expense of the city. Smith refers to these processes as uneven development (Figure 11.8). This type of explanation gives us a broad picture of the economic reasons that many cities are now decentralized. We will now look more closely at decentralization, examining the specific socioeconomic and public policy causes for the decentralization of our cities and for the problems that have resulted.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.9

In what ways does your city follow this hypothetical pattern? In what ways does it differ?

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.10

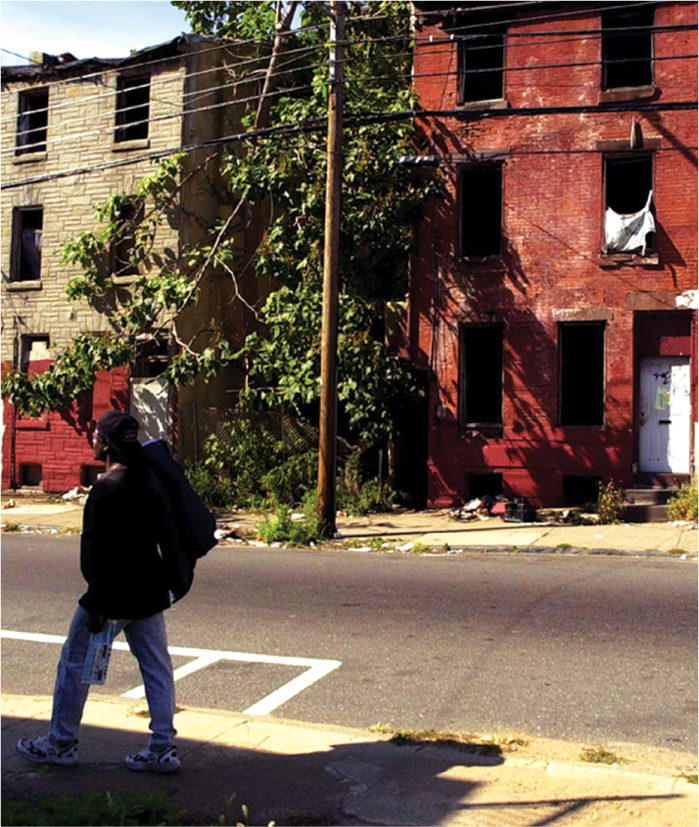

Under what circumstances were these houses once homes to the middle or upper classes?

Socioeconomic Factors

Socioeconomic Factors Changes in accessibility have been a major reason for decentralization. The department store that was originally located in the central city may now find that its customers have moved to the suburbs and no longer shop downtown. As a result, the department store may move to a suburban shopping mall. The same process affects many other industries as well. The activities that were located downtown because of its proximity to the railroad may now find trucking more cost effective. They relocate closer to a freeway system that skirts the downtown area. Finally, many offices now locate near airports so that their executives and salespeople can fly in and out more easily.

308

Although agglomeration once served as a centralizing force, its former benefits have now become liabilities in many downtown areas. These disadvantages include rising rents as a result of the high demand for space; congestion in the support system, which may cause delays in the supply chain or long lines at lunchtime; and traffic congestion, which makes delivery to market time-consuming and costly. Some downtown areas are so congested that traffic moves more slowly today than it did at the turn of the twentieth century. Often dissatisfied with the inconveniences of central-city living, employees may demand higher wages as compensation. This adds to the cost of doing business in the central city, and many firms choose to leave instead. For example, many firms have left New York City for the suburbs. They claim that it costs less to locate there and that their employees are happier and more productive because they do not have to put up with the turmoil of city life.

Clustering in new suburban locations can also have benefits. In industrial parks, for example, all the occupants share the costs of utilities and transportation links. Similar benefits can come from residential agglomeration. Suburban real estate developments take advantage of clustering by sharing the costs of schools, parks, road improvements, and utilities. New residents much prefer moving into a new development when they know that a full range of services is available nearby. Then they will not have to drive miles to find, say, the nearest hardware store. It is to the developer’s advantage to encourage construction of nearby shopping centers.

lateral commuting Traveling from one suburb to another between home and work.

The need to be near one’s workplace has historically been a great centralizing force, but it can also be a very strong decentralizing force. At first the suburbs were “bedroom communities” from which people commuted to their jobs in the downtown area. This is no longer the case. In many metropolitan areas, most jobs are not in the central city but in outlying districts. Now people work in suburban industrial parks, manufacturing plants, office buildings, and shopping centers. Thus, a typical journey to work involves lateral commuting: travel from one suburb to another. As a result, most people who live away from the city center actually live closer to their workplaces.

Reflecting on Geography

Question 11.11

Identify some of the efforts that your city has undertaken to create a better image of itself. Have these efforts been successful? Does this reimagining of the city actually help residents of the inner city?

The prestige of the downtown area might once have lured people and businesses into the central city. But once it begins to decay, once shops close and offices are empty, a certain stigma develops that may drive away residents and commercial activities. Investors will not sink money into a downtown area that they think has no chance of recovery, and shoppers will not venture downtown when streets are filled with vacant stores, transients, pawnshops, and secondhand stores. One of the persistent problems faced by cities is how to reverse this image of the downtown area so that people once again consider it the focus of the city.

Public Policy

Public Policy Many public policy decisions, particularly at the national level, have contributed greatly to the decentralization and abandonment of our cities. Both the Federal Road Act of 1916 and the Interstate Highway Act of 1956 directed government spending on transportation to the advantage of automobiles and trucks. Urban expressways, in combination with the emerging trucking industry, led to massive decentralization of industry and housing. In addition, the ability to deduct mortgage interest from income for tax purposes favors individual homeownership, which has tended to support a move to the suburbs.

309

The federal government in the United States has also intervened more directly in the housing market. In Crabgrass Frontier, Kenneth Jackson outlines the implications of two federal housing policies for the spatial patterning of our metropolitan areas. The first was the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934 and its supplement, known as the GI Bill, enacted in 1944. These federal acts, which insured long-term mortgage loans for home construction, were meant to provide employment in the building trades and to help house soldiers returning from World War II. Although the FHA legislation contained no explicit antiurban bias, most of the houses it insured were located in new residential developments in the suburbs, thereby neglecting the inner city.

Jackson identifies three reasons this happened. First, by setting particular terms for its insurance, the FHA favored the development of single-family over multifamily projects. Second, FHA-insured loans for repairs were of short duration and were generally small. Most families, therefore, were better off buying a new house that was probably in the suburbs than updating an older home in the city.

restrictive covenant A statement written into a property deed that limits the use of the land in some way; often used to prohibit certain groups of people from buying property.

redlining A practice by banks and mortgage companies of demarcating areas considered to be at high risk for defaulting on housing loans.

Jackson regards the third factor as the most important. To receive an FHA-insured loan, the applicant and the neighborhood of the property had to be assessed by an “unbiased professional.” This requirement was intended to guarantee that the property value of the house would be greater than the debt. This policy, however, encouraged bias against any neighborhood that was considered a potential risk in terms of property values. The FHA explicitly warned against neighborhoods with a racial mix, assuming that such a social climate would bring property values down, and it encouraged the inclusion of restrictive covenants in property deeds. These covenants restricted the use of the land in some way and often prohibited certain “undesirable” groups from buying property. The agency also prepared extensive maps of metropolitan areas depicting the locations of African-American families and predicting the spread of that population. These maps often served as the basis for redlining, a practice whereby banks and mortgage companies demarcated areas (often by drawing a red line around them on maps) considered to be at high risk for defaulting on housing loans.

These policies had two primary effects. First, they encouraged construction of single-family homes in suburban areas while discouraging central-city locations. Second, they intensified the segregation of residential areas and actively promoted homogeneity in the new suburbs.

The second federal housing policy that had a major impact on the patterning of metropolitan areas, the United States Housing Act, was intended to provide public housing for those who could not afford private housing. Originally implemented in 1937, the legislation did encourage the construction of many low-income housing units. Yet most of those units were built in the inner city, thereby contributing to the view of the suburbs as the refuge of the white middle class. This growing pattern of racial and economic segregation arose in part because public housing decisions were left up to local municipalities. Many municipalities did not need federal dollars and therefore did not want public housing. In addition, the legislation required that for every unit of public housing erected, one inferior housing unit had to be eliminated. Thus, only areas with inadequate housing units could receive federal dollars, again ensuring that public housing projects would be constructed in the older downtown areas, not the newer suburbs. As Jackson claims, “The result, if not the intent, of the public housing program of the United States was to segregate the races, to concentrate the disadvantaged in inner cities, and to reinforce the image of suburbia as a place of refuge from the problems of race, crime, and poverty.”

The Costs of Decentralization

The Costs of Decentralization Decentralization has taken its toll on North American cities. Many of the problems they now face are the direct result of the rapid decentralization that has taken place in the last 50 years. Those people who cannot afford to live in the suburbs are forced to live in inadequate and rundown housing in the inner city, areas that currently do not provide good jobs. Vacant storefronts, empty offices, and deserted factories testify to the movement of commercial functions from central cities to suburbs. Retail stores in North American central cities have steadily lost sales to suburban shopping centers. Even offices are finding advantages to suburban location when they can capitalize on lower costs and easier access to new transportation networks.

checkerboard development A mixture of farmlands and housing tracts. Also called leapfrog development.

Decentralization has also cost society millions of dollars in problems brought to the suburbs. Where rapid suburbanization has occurred, sprawl has usually followed. A common pattern is leapfrog or checkerboard development: housing tracts jump over parcels of farmland, resulting in a mixture of open lands with built-up areas. This pattern occurs because developers buy cheaper land farther away from built-up areas, thereby cutting their costs. Furthermore, home buyers are often willing to pay premium prices for homes in subdivisions surrounded by farmland (Figure 11.9). The developer’s gain is the area’s loss, for it is more expensive to provide city services—such as police, fire protection, sewers, and electrical lines—to those areas that lie beyond open parcels that are not built up. Obviously, the most cost-efficient form of development is the addition of new housing directly adjacent to built-up areas so that the costs of providing new services are minimal.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.12

Why are such street patterns sometimes called “loop and lollipop”? What problems does such a pattern cause for provision of services?

310

Sprawl also extracts high costs because of the increased use of cars. Public transportation is extremely costly and inefficient when it must serve a low-density checkerboard development pattern—so costly that many cities and transit firms cannot extend lines into these areas. This means that the automobile is the only form of transportation. More energy is consumed for fuel, more air pollution is created by exhaust, and more time is devoted to commuting and everyday activities in a sprawling urban area than in a centralized city.

Moreover, we should not overlook the costs of losing valuable agricultural land to urban development. Farmers cultivating the remaining checkerboard parcels have a hard time earning a living. They are usually taxed at extremely high rates because their land has high potential for development, and few can make a profit when taxes eat up all their resources. Often the only recourse is to sell out to subdividers. So the cycle of leapfrog development goes on.

in-filling New building on empty parcels of land within a checkerboard pattern of development.

Many cities are now taking strong measures to curb this kind of sprawling growth. San José, California, for example, one of the fastest-growing cities of the 1960s, is now focusing new development on empty parcels of the checkerboard pattern. This is called in-filling. Other cities are tying the number of building permits granted each year to the availability of urban services. If schools are already crowded, water supplies inadequate, and sewage plants overburdened, the number of new dwelling units approved for an area will reflect this lower carrying capacity.

Gentrification

Gentrification

gentrification The displacement of lower-income residents by higher-income residents as buildings in deteriorated areas of city centers are restored.

Beginning in the 1970s, urban scholars observed what seemed to be a trend opposite to suburbanization. This trend, called gentrification, is the movement of middle-class people into deteriorated areas of city centers. Gentrification often begins in an inner-city residential district, with gentrifiers moving into an area that had been run down and is therefore more affordable than suburban housing (Figure 11.10). The infusion of new capital into the housing market usually results in higher property values, and this, in turn, often displaces residents who cannot afford the higher prices. Displacement opens up more housing for gentrification, and the gentrified district continues its spatial expansion.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.13

Why does gentrification often take place in a neighborhood close to downtown?

Commercial gentrification usually follows residential, as new patterns of consumption are introduced into the inner city by the middle-class gentrifiers. Urban shopping malls and pedestrian shopping corridors bring the conveniences of the suburbs into the city, and bars and restaurants catering to this new urban middle class provide entertainment and nightlife for the gentrifiers.

The speed with which gentrification has proceeded in many of our downtowns and the scale of landscape changes that accompany it are causing dramatic shifts in the urban mosaic. What factors have led to this reshaping of our cities?

Economic Factors

Economic Factors Some urban scholars look to broad economic trends in the United States to explain gentrification. We already know from our discussion of suburbanization that throughout the post–World War II era most investments in metropolitan land were made in the suburbs; as a result, land in the inner city was devalued. By the 1970s, many home buyers and commercial investors found land in the city much more affordable, and a better economic investment, than in the higher-priced suburbs. This situation brought capital into areas that had been undervalued and accelerated the gentrifying process.

311

deindustrialization The decline of primary and secondary industry, accompanied by a rise in the service sectors of the industrial economy.

In addition, most Western countries have been experiencing deindustrialization, a process whereby the economy is shifting from one based on primary and secondary industry to one based on the service sector. This shift has led to the abandonment of older industrial districts in the inner city, including waterfront areas. Many of these areas are prime targets of gentrifiers, who convert the waterfront from a noisy, commercial port area into an aesthetic asset. In Buenos Aires, for example, one of the new gentrified neighborhoods is Puerto Madero, an area that was once home to docking facilities and a wholesale market (Figure 11.11). The shift to an economy based on the service sector also means that the new productive areas of the city will be dedicated to white-collar activities. These activities often take place in relatively clean and quiet office buildings, contributing to a view of the city as a more livable environment.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.14

Is there anything that marks this gentrified district as being located in Buenos Aires, instead of, say, New York City?

Social Factors

Social Factors Other scholars look to changes in social structure to explain gentrification. The maturing of the baby-boom generation has led to significant modifications of our traditional family structure and lifestyle. With a majority of women in the paid labor force and many young couples choosing not to have children or to delay that decision, a suburban residential location looks less appealing. A gentrified location in the inner city attracts this new class because it is close to managerial or professional jobs downtown, is usually easier to maintain, and is considered more interesting than the bland suburban areas of childhood. Living in a newly gentrified area is also a way to display social status. Many suburbs have become less exclusive, while older neighborhoods in the inner city frequently exploit their historical associations as a status symbol.

312

Political Factors

Political Factors Many metropolitan governments in the United States, faced with the abandonment of the central city by the middle class and therefore the erosion of their tax base, have enacted policies to encourage commercial and residential development in downtown areas. Some policies provide tax breaks for companies willing to locate downtown; others furnish local and state funding to redevelop central-city residential and commercial buildings.

At a more comprehensive level, some larger metropolitan areas have devised long-term planning agendas that target certain neighborhoods for revitalization. Often this is accomplished by first condemning the targeted area, thereby transferring control of the land to an urban-development authority or other planning agency. Such areas are often older residential neighborhoods that were originally built to house people who worked in nearby factories, which are usually torn down or transformed into lofts or office space. The redevelopment authority might locate a new civic or arts center in the neighborhood. Public-sector initiatives often lead to private investment, thereby increasing property values. These higher property values in turn lead to further investment and the eventual transformation of the neighborhood into a middle- to upper-class gentrified district.

Sexuality and Gentrification

Sexuality and Gentrification Gentrified residential districts are often correlated with the presence of a significant gay and lesbian population. It is fairly easy to understand this correlation. First, the typical suburban life tends not to appeal to people whose lifestyle is often regarded as different and whose community needs are often different from those of people living in the suburbs. Second, gentrified inner-city neighborhoods provide access to the diversity of city life and amenities that often include gay cultural institutions. In fact, the association of urban neighborhoods with gays and lesbians has a long history. For example, urban historian George Chauncey has documented gay culture in New York City between 1890 and World War II, showing that a gay world occupied and shaped distinctive spaces in the city, such as neighborhood enclaves, gay commercial areas, and public parks and streets.

Yet, unlike this earlier period, when gay cultures were often forced to remain hidden, the gentrification of the postwar period has provided gay and lesbian populations with the opportunity to reshape entire neighborhoods actively and openly. Urban scholar Manuel Castells argues that in cities such as San Francisco, the presence of gay men in institutions directly linked to gentrification, such as the real estate industry, significantly influenced that city’s gentrification processes in the 1970s.

Geographers Mickey Lauria and Lawrence Knopp emphasize the community-building aspect of gay men’s involvement in gentrification, recognizing that gays have seized an opportunity to combat oppression by creating neighborhoods over which they have maximum control and that meet long-neglected needs. Similarly, geographer Gill Valentine argues that the limited numbers and types of lesbian spaces in cities also serve as community-building centers for lesbian social networks.

According to geographer Tamar Rothenberg, the gentrified neighborhood of Park Slope in Brooklyn is home to the heaviest concentration of lesbians in the United States. Its extensive social networks are marking the neighborhood as both a center of lesbian identity and a visible lesbian social space.

The Costs of Gentrification

The Costs of Gentrification Gentrification often results in the displacement of lower-income people, who are forced to leave their homes because of rising property values. This displacement can have serious consequences for the city’s social fabric. Because many of the displaced people come from disadvantaged groups, gentrification frequently contributes to racial and ethnic tensions. Displaced people are often forced into neighborhoods more peripheral to the city, a trend that only adds to their disadvantages. In addition, gentrified neighborhoods usually stand in stark contrast to surrounding areas where investment has not taken place, thus creating a very visible reminder of the uneven distribution of wealth within cities.

The success of a gentrification project is usually measured by its appeal to an upper-middle-class clientele. This suggests that gentrified neighborhoods are completely homogeneous in their use of land. Residential areas are consciously planned to be separate from commercial districts and are themselves sorted by cost and tenure type (homeownership versus rental). Thus, gentrification often draws on the suburban notion of residential homogeneity and eliminates what many people consider to be a great asset of urban life—its diversity and heterogeneity.

Immigration and New Ethnic Neighborhoods

Immigration and New Ethnic Neighborhoods

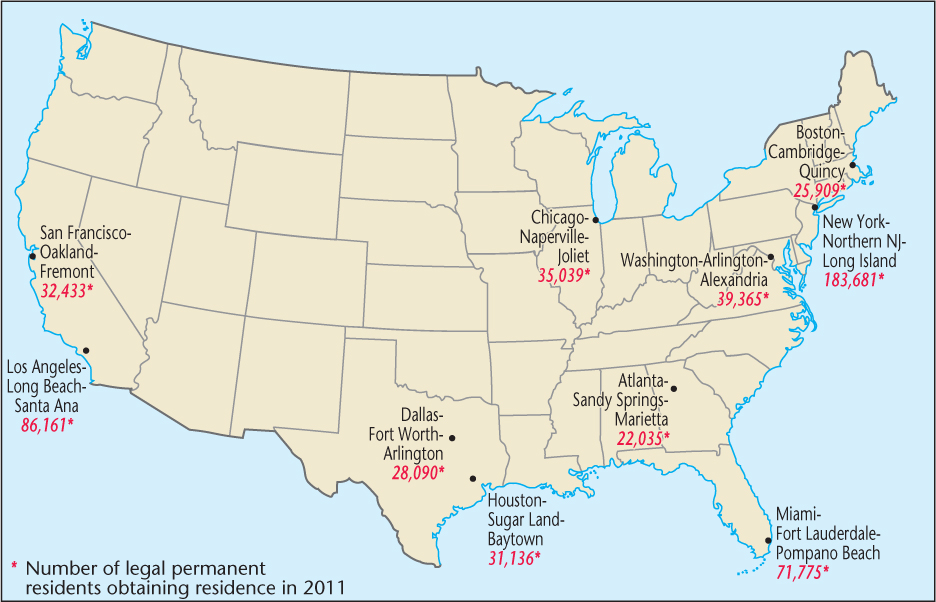

According to the United States Department of Homeland Security, approximately 3.2 million people immigrated to the United States as “legal permanent residents” between 2009 and 2011: 39.5 percent came from Latin America and the Caribbean, 39.7 percent from Asia, 9.9 percent from Europe and Canada, and 10.9 percent from other regions. The vast majority of these immigrants found job opportunities and cultural connections that drew them to major metropolitan regions in six states—California, New York, Florida, Texas, New Jersey, and Illinois (Figure 11.12). This spatial concentration of America’s new immigrants has created diverse communities with distinctive landscapes, both within the downtown areas of these cities and in the suburban regions. Miami’s Little Havana, for example, is easily recognized by the commercial signs in Spanish, Spanish street names, and the colors and styles of buildings. Parts of what were once run-down neighborhoods of the city have been remade into vibrant commercial and residential communities.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.15

Why is immigration focused on these particular cities?

313

ethnoburb A suburban ethnic neighborhood, sometimes home to a relatively affluent immigration population.

These new ethnic landscapes are not limited to the central city. Portions of America’s suburbs have also become diverse. The decentralization of the downtown has created new economic centers in suburban regions, and immigrants are drawn to these centers. According to the 2010 census, nationwide approximately 51 percent of new immigrants to the United States are now living in suburbs of large metropolitan areas. Geographer Wei Li refers to these new immigrant communities located in the suburbs as ethnoburbs. Instead of the dense residential and commercial districts that characterize downtown ethnic enclaves, the new suburban ethnicity is proclaimed within shopping centers, suburban cemeteries, and dispersed houses of worship. According to geographer Joseph Wood, their presence in the landscape is often not visible to observers precisely because the landscape is suburban. For example, most of the 50,000 Vietnamese-Americans who migrated to the Washington, D.C., area from the 1970s through the 1990s settled in suburbs in northern Virginia. The focal point of the Vietnamese community there is the Eden Center, a typical l-shaped shopping center that has been transformed into a Vietnamese-American economic and social center (Figure 11.13). This pattern of shopping plazas serving as ethnic community markers for a dispersed immigrant population is not peculiar to northern Virginia; it is commonplace in the metropolitan areas of most major North American cities.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.16

Compare this center to a traditional urban ethnic neighborhood.

314

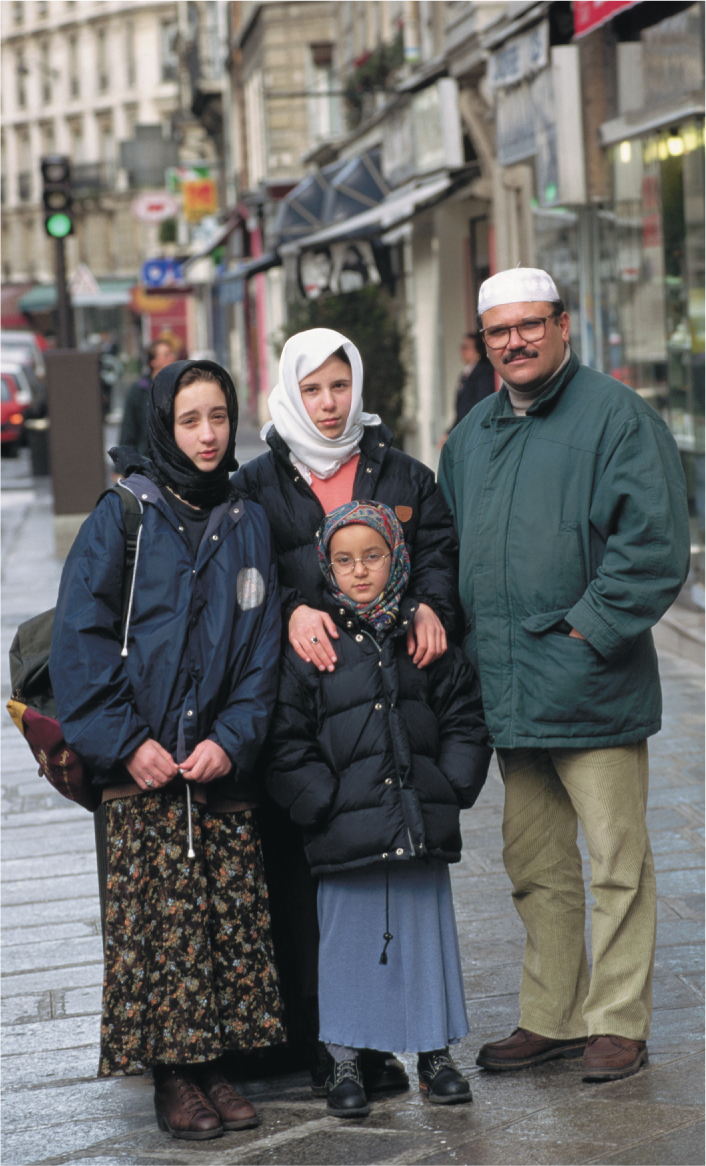

Urban ethnic enclaves are not limited to U.S. and Canadian cities. Many cities around the world are experiencing the effects of immigration as globalization makes it easier for people from one country to seek employment in thriving metropolitan areas of a different country. There are North African communities in Paris (Figure 11.14), Turkish neighborhoods in Berlin, and Kurdish neighborhoods in Istanbul, and each of these is influencing the culture, economy, and landscape of these cities in profound ways.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.17

How are these ethnic enclaves related to globalization?