Cultural Interaction and Models of the City

Cultural Interaction and Models of the City

Are there generalizable spatial patterns or models that describe types of cities? Geographers are interested in understanding both the uniqueness of each city’s urban pattern and the similarities that a particular city may have with others. To provide insights about the diverse human mosaic, geographers have tried to describe some spatial models of land use within cities, each of which helps us understand a particular type of city. Let us remember, though, that these models were constructed to examine single cities and do not necessarily apply to the metropolitan coalescences so common in the world today.

317

Concentric-Zone Model

Concentric-Zone Model

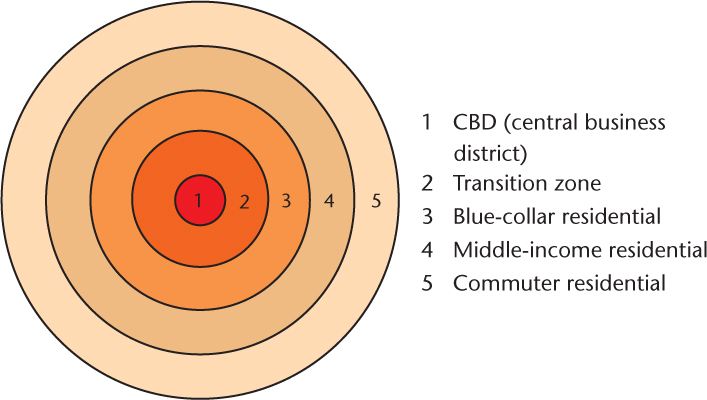

The concentric-zone model was developed in 1925 by Ernest W. Burgess, a sociologist at the University of Chicago. Figure 11.18 shows the concentric-zone model with its five zones. Although not shown in the figure, there is a distinct pattern of income levels from zone 1, the CBD, out to the commuter residential zone. This pattern shows that even at the beginning of the automobile age, American cities expressed a clear separation of social groups. The extension of trolley lines into the surrounding countryside had a lot to do with this pattern.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.21

Can you identify examples of each zone in your community?

concentric-zone model A social model developed by Ernest Burgess that depicts a city as five areas bounded by concentric rings.

Zone 2, a transitional area between the CBD and residential zone 3, is characterized by a mixed pattern of industrial and residential land use. Rooming houses, small apartments, and tenements attract the lowest-income segment of the urban population. Often this zone includes slums and skid rows. In the past, many ethnic ghettos took root here as well. Landowners, while waiting for the CBD to reach their land, erected shoddy tenements to house a massive influx of foreign workers. An aura of uncertainty was characteristic of life in zone 2, because commercial activities rapidly displaced residents as the CBD expanded. Today, this area is often characterized by physical deterioration (Figure 11.19).

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.22

Why has this area become a likely target for gentrification?

Zone 3, the “workingmen’s quarters,” is a solid blue-collar arc, located close to the factories of zones 1 and 2. Yet zone 3 is more stable than the zone of transition around the CBD. It is often characterized by ethnic neighborhoods: blocks of immigrants who broke free from the ghettos in zone 2 and moved outward into flats or single-family dwellings. Burgess suggested that this working-class area, like the CBD, was spreading outward because of pressure from the zone of transition and because blue-collar workers demanded better housing.

Zone 4 is a middle-class area of better housing. From here, established city dwellers—many of whom moved out of the central city with the construction of the first streetcar network—commute to work in the CBD.

Zone 5, the commuters’ zone, consists of higher-income families clustered in suburbs, either on the farthest extension of the trolley or on commuter railroad lines. This zone of spacious lots and large houses is the growing edge of the city. From here, the rich press outward to avoid the increasing congestion and social heterogeneity brought to their area by an expansion of zone 4.

Burgess’s concentric-zone theory represented the American city in a new stage of development. Before the 1870s, an American metropolis, such as New York, was a city of mixed neighborhoods where merchants’ stores and sweatshop factories were intermingled with mansions and hovels. Rich and poor, immigrant and native-born rubbed shoulders in the same neighborhoods. However, in Chicago, Burgess’s hometown, something else occurred. In 1871, the Great Chicago Fire burned down the core of the city, leveling almost one-third of its buildings. As the city was rebuilt, it was influenced by late-nineteenth-century market forces: real estate speculation in the suburbs, inner-city industrial development, new streetcar systems, and the need for low-cost working-class housing. The result was more clearly demarcated social patterns than existed in other large cities. Chicago became a segregated city with a concentric pattern working its way out from the downtown in what one scholar called “rings of rising affluence.” It was this rebuilt city that Burgess used as the basis for his concentric zone model.

318

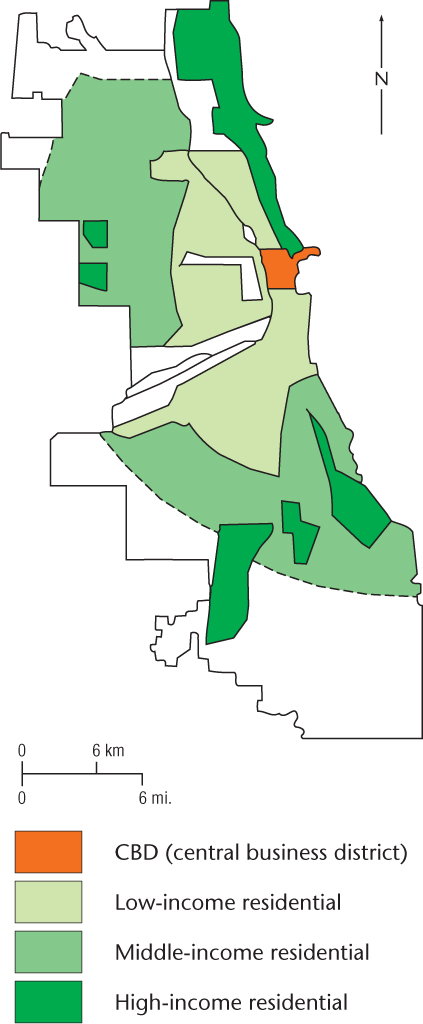

However, as you can see from Figure 11.20, the actual residential map of Chicago does not exactly match the simplicity of Burgess’s concentric zones. For instance, it is evident that the wealthy continue to monopolize certain high-value sites within the other rings, especially Chicago’s Gold Coast along Lake Michigan on the Near North Side. According to the concentric-zone theory, this area should have been part of the zone of transition. Burgess accounted for some of these exceptions by noting how the rich tended to monopolize hills, lakes, and shorelines, whether they were close to or far from the CBD. Critics of Burgess’s model also were quick to point out that even though portions of each zone did exist in most cities, rarely were they linked in such a way as to totally surround the city. Burgess countered that there were distinct barriers, such as old industrial centers, that prevented the completion of the arc. Still other critics felt that Burgess, as a sociologist, overemphasized residential patterns and did not give proper credit to other land uses—such as industry, manufacturing, and warehouses—in describing urban patterns.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.23

Compare this pattern with the concentric-zone and sector models.

Though the concentric-zone model retains its historical legacy as a key contribution to theories of urban development, contemporary urban geographers highlight its failure to accurately describe many modern cities, particularly those outside of the United States. Different historical contexts in other countries caused cities to develop in quite different ways from U.S. cities. For example, in European cities, historically, the highest-rent zones are close to city centers, while lower-rent areas are often farther away. Even in the United States, due to changes in transportation and information technology, there are often no longer clear zones of economic activity and residence. For example, telecommuters may conveniently live in many different areas of a city, and many businesses are now meeting their locational needs in the suburbs rather than in the CBD. So as businesses, retail stores, and restaurants decentralize to accommodate increasingly diverse residential patterns, the concentric-zone model becomes less applicable.

Sector Model

Sector Model

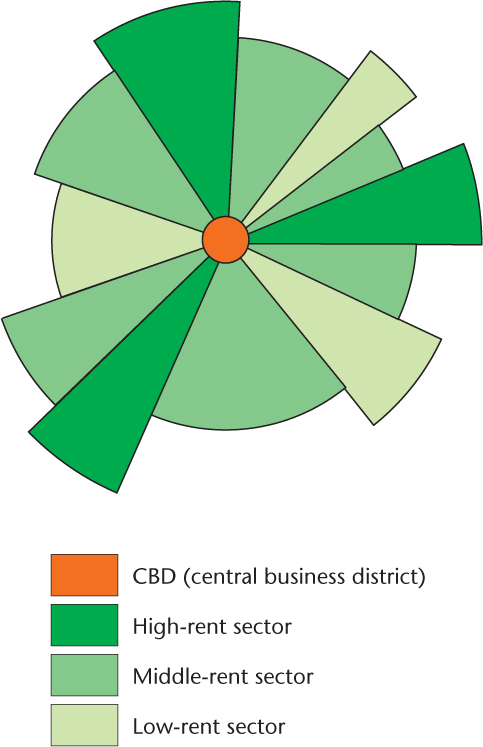

sector model An economic model, developed by Homer Hoyt, that depicts a city as a series of sectors or wedges shaped like the slices of a pie.

Homer Hoyt, an economist who studied housing data for 142 American cities, presented his sector model of urban land use in 1939. He maintained that high-rent residential districts (rent meaning capital outlay for the occupancy of space, including purchase, lease, or rent in the popular sense) were instrumental in shaping the land-use structure of the city. Because these areas were reinforced by transportation routes, the pattern of their development was one of sectors or wedges shaped like the slices of a pie (Figure 11.21), not concentric zones.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.24

Does this model reflect reality more than the concentric-zone model? How?

Hoyt suggested that the high-rent sector would expand according to four factors. First, a high-rent sector moves from its point of origin near the CBD along established routes of travel toward another nucleus of high-rent buildings. That is, a high-rent area directly next to the CBD will naturally head in the direction of a high-rent suburb, eventually linking the two in a wedge-shaped sector. Second, this sector will progress toward high ground or along waterfronts when these areas are not used for industry. The rich have always preferred such environments for their residences. Third, a high-rent sector will move along the route of fastest transportation. Fourth, it will move toward open space. A high-income community rarely moves into an occupied lower-income neighborhood. Instead, the wealthy prefer to build new structures on vacant land where they can control the social environment.

319

As high-rent sectors develop, the areas between them are filled in. Middle-rent areas move directly next to them, drawing on their prestige. Low-rent areas fill in the remaining areas. Thus, moving away from major routes of travel, rents go from high to low.

There are distinct patterns in today’s cities that echo Hoyt’s model. He had the advantage over Burgess in that he wrote later in the automobile age and could see the tremendous impact that major thoroughfares were having on cities. However, when we look at today’s major transportation arteries, which are generally freeways, we see that the areas surrounding them are often low-rent districts. According to Hoyt’s theory, they should be high-rent districts. Freeways are rather recent additions to the city, coming only after World War II, which were imposed on an existing urban pattern. To minimize the economic and political costs of construction, they were often built through low-rent areas, where the costs of land purchase for the rights-of-way were less and where political opposition was kept to a minimum because most people living in these low-rent areas had little political clout. This is why so many freeways rip through ethnic ghettos and low-income areas. Economically speaking, this is the least expensive route.

As with the concentric-zone model, emerging patterns of telecommuting and the growth of suburban “commuter villages” have reduced the applicability of the sector model to modern urban development. In fact, rather than following the sector-type pattern that Hoyt predicted, “leapfrog” urban development has occurred in many areas, resulting in districts of economic activity and residential status that are quite irregular in pattern. Furthermore, following World War II, many cities around the world began to adopt urban planning policies that restricted certain land uses to particular areas of a city. Therefore, patterns of land use in contemporary cities have often strayed significantly from a sector pattern in order to accommodate the preservation of green areas and historical districts, for example.

Multiple-Nuclei Model

Multiple-Nuclei Model

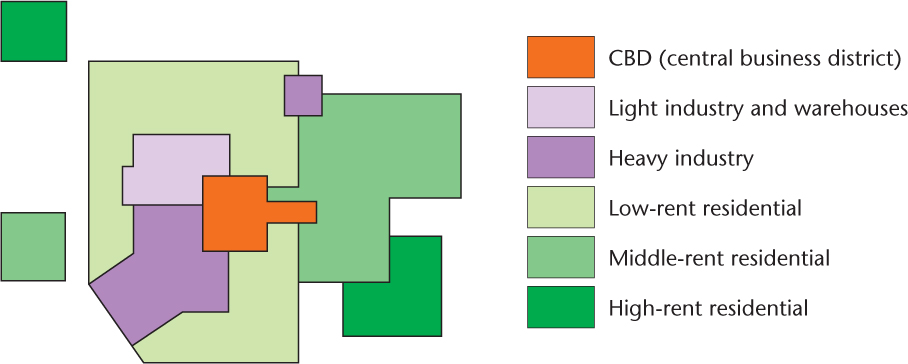

multiple-nuclei model A model, developed by Chauncey Harris and Edward Ullman, that depicts a city growing from several separate focal points.

Both Burgess and Hoyt assumed that a strong central city affected patterns throughout the urban area. However, as cities increasingly decentralized, districts developed that were not directly linked to the CBD. In 1945, two geographers, Chauncey Harris and Edward Ullman, suggested a new model: the multiple-nuclei model. They maintained that a city developed with equal intensity around various points, or multiple nuclei (Figure 11.22). In their eyes, the CBD was not the only focus of activity. Equal weight had to be given to an old community on the city outskirts around which new suburban developments clustered; to an industrial district that grew from an original waterfront location; or to a low-income area that developed because of some social stigma attached to the site.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.25

Compare this model to Figure 11.21. How and why are they different?

320

Harris and Ullman rooted their model in four geographical principles. First, certain activities require highly specialized facilities, such as accessible transportation for a factory or large areas of open land for a housing tract. Second, certain activities cluster because they profit from mutual association. Car dealers, for example, are commonly located near one another because automobiles are very expensive and so people will engage in comparative shopping—moving from one dealer to another until their decisions are made. Third, certain activities repel each other and will not be found in the same area. Examples would be high-rent residences and industrial areas, or slums and expensive retail stores. Fourth, certain activities could not make a profit if they paid the high rent of the most desirable locations and would therefore seek lower-rent areas. For example, furniture stores may like to locate where pedestrian traffic is greatest to lure the most people into their showrooms. However, they need large amounts of space for showrooms and storage. Thus, they cannot afford the high rents that the most accessible locations demand. They compromise by finding an area of lower rent that is still relatively accessible.

The multiple-nuclei model, more than the other models, seems to take into account the varied factors of decentralization in the structure of the North American city. Many geographers criticize the concentric-zone and sector models as being rather simplistic, for they emphasize a single factor (residential differentiation in the concentric-zone model and rent in the sector model) to explain the pattern of the city. The multiple-nuclei model encompasses a larger spectrum of economic and social factors. Harris and Ullman could probably accommodate the variety of forces working on the city because they did not confine themselves to seeking simply a social or economic explanation.

The multiple-nuclei model has three additional strengths. First, it takes into account the fragmentation of urban areas so common in many developed countries today. Second, it considers the process of suburbanization. Third, the multiple-nuclei model can take into account specialized economic functions such as heavy versus light manufacturing. The multiple-nuclei model’s ability to incorporate these contemporary realities increases the applicability of Harris and Ullman’s work to many modern cities. However, though the multiple-nuclei model integrates many different elements of culture and economics, caution must always be used when applying it to real-world situations. Cities within the United States and around the world have developed differently in many historical and cultural contexts. Therefore, the study of cities through any land-use model or models must take this variability into account. Nevertheless, due to its acknowledgment of modern transportation, technology, and lifestyles, the multiple-nuclei model may offer greater insight into contemporary urban studies than earlier models of the city did.

Critiques of the Models

Critiques of the Models

Most of the criticisms of the models just discussed focus on their simplification of reality or their inability to account for all the complexities of actual urban forms. More recently, feminist geographers have noticed some flaws in the models and in how they were constructed that call into question their descriptive power.

All three models assume that urban patterns are shaped by an economic trade-off between the desire to live in a suburban neighborhood appropriate to one’s economic status and the need to live relatively close to the central city for employment opportunities. These models assume that only one person in the family is a wage worker—the male head of the family. They ignore dual-income families and households headed by single women, who contend with a larger array of factors in making locational decisions, including distances to child-care and school facilities and other services important for other members of a family. For many of these households, the traditional urban models that assume a spatial separation of workplace and home are no longer appropriate.

For example, a study of the activity patterns of working parents shows that women living in a city have access to a wider array of employment opportunities and are better able to combine domestic and wage labor than are women who live in the suburbs. Many of these middle-class women will choose to live in a gentrified inner-city location, hoping that this type of area will offer the amenities of the suburbs (good schools and safety) while also accommodating their work schedules. Other research has shown that some businesses will locate their offices in the suburbs because they rely on the labor of highly educated, middle-class women who are spatially constrained by their domestic work. As geographers Susan Hanson and Geraldine Pratt found in their study of employment practices and gender in Worcester, Massachusetts, most women seek employment locations closer to their homes than do men, and this applies to almost all women, not just those with small children.

The traditional models are also criticized for being created by men who all shared certain assumptions about how cities operate and thus presented a very limited view of urban life. Geographers David Sibley and Emily Gilbert, for instance, have both brought to our attention the development of other theories about urban form and structure during the same time. These theories incorporate the alternative perspectives of female scholars. Drawing on the urban reform work done by Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago, scholars in the first decades of the twentieth century examined the causes of and possible solutions to urban problems. For example, Edith Abbott, Sophonisba Breckinridge, and Helen Rankin Jeter, faculty at the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago, worked with their mostly female students to produce a number of studies about “race,” ethnicity, class, and housing in Chicago. These studies differed in several ways from those of such theorists as Burgess and Hoyt. For instance, they emphasized the role of landlords in shaping the housing market and included an awareness of how racism is related to the allocation of housing and a sensitivity to the different urban experiences of ethnic groups.

321

Much of what these researchers at the School of Social Service uncovered in the 1930s is applicable to urban areas today. For example, a study by urban historian Raymond Mohl chronicles the making of black ghettos in Miami between 1940 and 1960. His research reveals the role of public policy decisions, landlordism, and discrimination in that process—forces identified by Abbott and others that continue to operate today.