Urban Landscapes

Urban Landscapes

cityscape An urban landscape.

What do the urban patterns we have been discussing look like? How can we recognize different types of cities from their three-dimensional forms, and how are these forms changing? Cities, like all places humans inhabit, demonstrate an intriguing array of cultural landscapes, the reading of which gives varied insights into the complicated interactions between people and their surroundings. In this section, we offer some thoughts about how to view and read urban landscapes. We begin by discussing some geographical reference points—one might say helpful hints—for investigating and reading cityscapes. You will find that you have a great deal of intuitive knowledge about cityscapes.

Ways of Reading Cityscapes

Ways of Reading Cityscapes

urban morphology The form and structure of cities, including street patterns, building sizes and shapes, architecture, and density.

functional zonation The pattern of land uses within a city; the existence of areas with differing functions, such as residential, commercial, and governmental.

What do cities look like? Understanding urban landscapes requires an appreciation of large-scale urbanizing processes and local urban environments both past and present. The patterns we see today in the city, such as building forms, architecture, street plans, and land use, are a composite of past and present cultures. They reflect the needs, ideas, technology, and institutions of human occupancy. Two concepts underlie our examination of urban landscapes. The first is urban morphology, or the physical form of the city, which consists of street patterns, building sizes and shapes, architecture, and density. The second concept is functional zonation, which refers to the pattern of land uses within a city or, put another way, the existence of areas with differing functions, such as residential, commercial, and governmental. Functional zonation also includes social patterns—whether, for example, an area is occupied by the power elite or by people of low status, by Jews or by Christians, by the wealthy or by the poor. Both concepts are central to understanding the cultural landscape of cities, because both make statements about how cultures occupy and shape space.

Cultural geographers look to cityscapes for many different kinds of information. Here we discuss four inter-connected themes that are commonly used as organizational frameworks for landscape research (Figure 11.23).

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.26

Which clues would you select to illustrate each cityscape theme?

322

Landscape Dynamics

Landscape Dynamics Think of some familiar features of the cityscape: downtown activities creeping into residential areas, deteriorated farmland on a city’s outskirts, older buildings demolished for the new. These are all signs of specific processes that create urban change; the landscape faithfully reflects these dynamics.

When these visual clues are systematically mapped and analyzed, they offer evidence for the currents of change expressed in our cities. Of equal interest is where change is not occurring—those parts of the city that for various reasons remain relatively static. An unchanging landscape also conveys an important message. Perhaps that part of the city is stagnant because it is removed from the forces that produce change in other parts. Or perhaps there is a conscious attempt by local residents to inhibit change—to preserve open space by resisting suburban development, for example, or to preserve a historic landmark. Documenting landscape changes over time gives valuable insight into the paths of settlement development.

The City as Palimpsest

palimpsest A term used to describe cultural landscapes with various layers and historical messages. Geographers use this term to reinforce the notion of the landscape as a text that can be read; a landscape palimpsest has elements of both modern and past periods.

The City as Palimpsest Because cityscapes change, they offer a rich field for uncovering remnants of the past. A palimpsest is an old parchment used repeatedly for written messages. Before a new missive was written, the old was erased, yet rarely were all the previous characters and words obliterated—so remnants of earlier messages were still visible. This record of old and new is called a palimpsest, a word geographers use fondly to describe the visual mixture of past and present in cultural landscapes.

Cities are full of palimpsestic offerings, scattered across the contemporary landscape. How often have you noticed a Victorian farmhouse surrounded by new tract homes, or a historic street pattern obscured or highlighted by a recent urban redevelopment project, or a brick factory shadowed by new high-rise office buildings? All of these give clues to past settlement patterns, and all are mute testimony to the processes of change in the city.

Our interest in this historical accumulation is more than romantic nostalgia. A systematic collection of these urban remnants provides us with glimpses of the past that might otherwise be hidden. All societies pick and choose, consciously or not, what they wish to preserve for future generations, and, in this process, a filtering takes place that often excludes and distorts information, but the landscape does not lie.

Symbolic Cityscapes

Symbolic Cityscapes Landscapes contain much more than literal messages. They are also loaded with figurative or metaphorical meaning and can elicit emotions and memories. To some people, skyscrapers are more than high-rise office buildings: they are symbols of progress, economic vitality, downtown renewal, or corporate identities. Similarly, historical landscapes—those parts of the city where the past has been preserved—help people to define themselves in time; establish social continuity with the past; and codify a largely forgotten, yet sometimes idealized, past.

D. W. Meinig, a geographer who has given much thought to urban landscapes, maintains that there are three highly symbolic townscapes in the United States: the New England village, with its white church, common, and tree-lined neighborhoods; Main Street of Middle America, a string street of a small midwestern town, with storefronts, bandstand, and park (Figure 11.24); and what Meinig calls California Suburbia, suburbs of quarter-acre lots, effusive garden landscaping, swimming pools, and ranch-style houses. As Meinig explains: “Each is based upon an actual landscape of a particular region. Each is an image derived from our national experience…simplified…and widely advertised so as to become a commonly understood symbol. Each has…influenced the shaping of the American scene over broader areas.”

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.27

In what ways is Main Street used symbolically in art, literature, film, and television? What messages and emotions are conveyed by this landscape?

323

More politically and problematically, the cultural landscape is an important vehicle for constructing and maintaining, subtly and implicitly, certain social and ethnic distinctions. For example, geographers James and Nancy Duncan have found that because conspicuous consumption is a major way of conveying social identity in our culture, elite landscapes are created through large-lot zoning, imitation country estates, and the preservation of undeveloped land. They see the residential landscapes in upper-income areas as controlled and managed to reinforce class and status categories. Their study of elite suburbs near Vancouver and New York sensitizes us to how the cultural landscape can be thought of as a repository of symbols used by our society to differentiate itself and protect vested interests.

Perception of the City

Perception of the City During the last 25 years, geographers have been concerned with measuring people’s perceptions of the urban landscape. They assume that if we really know what people see and react to in the city, we can ask architects and urban planners to design and create a more humane urban environment.

Kevin Lynch, an urban designer, pioneered a method for recording people’s images of the city. On the basis of interviews conducted in Boston, Jersey City (New Jersey), and Los Angeles, Lynch suggested five important elements in mental maps (images) of cities:

- Pathways are the routes of frequent travel, such as streets, freeways, and transit corridors. We experience the city from the pathways, and they become the threads that hold our maps together.

- Edges are boundaries between areas or the outer limits of our image. Mountains, rivers, shorelines, and even major streets and freeways are commonly used as edges. They tend to define the extremes of our urban vision. Then we fill in the details.

- Nodes are strategic junction points, such as breaks in transportation, traffic circles, or any place where important pathways come together.

- Districts are small areas with a common identity, such as ethnic areas and functional zones (for instance, the CBD or a row of car dealers).

- Landmarks are reference points that stand out because of shape, height, color, or historical importance. The city hall in Los Angeles, the Washington Monument, and the golden arches of a McDonald’s are all landmarks.

legible (A city that is) easy to decipher, with clear pathways, edges, nodes, districts, and landmarks.

Using these concepts, Lynch saw that some parts of the cities were more legible, or easier to decipher, than others. Lynch discovered that in general legibility increases when the urban landscape offers clear pathways, nodes, districts, edges, and landmarks. Further, some cities are more legible than others. For example, Lynch found that Jersey City is not very legible. Wedged between New York City and Newark, Jersey City is fragmented by railroads and highways. Residents’ mental maps of Jersey City have large blank areas in them. When questioned, they can think of few local landmarks. Instead, they tend to point to the New York City skyline just across the Hudson River.

Megalopolis and Edge Cities

Megalopolis and Edge Cities

megalopolis A large urban region formed as several urban areas spread and merge, such as Boswash, the region including Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

In the nineteenth century, U.S. and Canadian cities grew at unprecedented rates because of the concentration of people and commerce. The inner city became increasingly dominated by commerce and the working class. In the twentieth century, particularly after World War II, new forms of transportation and communication led to the decentralization of many urban functions. As a result, one metropolitan area blends into another, until supercities stretch for hundreds of miles. The geographer Jean Gottmann coined the term megalopolis to describe these supercities.

This term is now used worldwide in reference to giant metropolitan regions such as Boston–New York–Philadelphia–Washington, D.C. in the United States and Tokyo-Yokohama in Japan. These urban regions are characterized by high population densities extending over hundreds of square miles or kilometers; concentrations of numerous older cities; transportation links formed by freeways, railroads, air routes, and rapid transit; and an extremely high proportion of the nation’s wealth, commerce, and political power.

edge city A new urban cluster of economic activity that surrounds a nineteenth-century downtown.

The past 25 years have witnessed an explosion in metropolitan growth in areas that had once been peripheral to the central city. Many of the so-called bedroom communities of the post–World War II era have been transformed into urban centers, with their own retail, financial, and entertainment districts (Figure 11.25). Author Joel Garreau refers to these new centers of urban activity, which surround nineteenth-century downtowns, as edge cities, although many other terms have been used in the past, including suburban downtowns, galactic cities, and urban villages. As Garreau mentions, most Americans now live, work, play, worship, and study in this type of settlement. What differentiates an edge city from the suburbs is that it is a place of work, of productive economic activity, and therefore is the destination of many commuters. In fact, the conventional work commute from the suburbs to the inner city has been replaced by commuting patterns that completely encircle the inner city. People live in one part of an edge city and commute to their workplace in another part of that city.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.28

Why have such developments grown up along circumferential highways and interstates?

324

peripheral model A geographic model created by Chauncey Harris that explains how suburban edge cities are linked by ring roads or beltways that allow for commuter traffic to conveniently avoid passing through major urban centers.

This commuting pattern, now common in many North American urban areas, is explained by the peripheral model. First conceived by Chauncey Harris (co-creator of the multiple-nuclei model), the peripheral model describes how large suburban residential and business areas are functionally tied together by beltways or ring roads. These transportation corridors allow residents to commute within or between edge cities without ever having to pass through the major city center nearby. Though convenient for suburban commuters and advantageous for businesses located in edge cities, this pattern of suburban transportation flow brings with it some disadvantages as well. The cost of constructing new roads through and between edge cities is significant, and green spaces and agricultural lands are often lost in the process. In European suburbs, these issues have been addressed by planning for circular “greenbelts” of open land between roadways and for the preservation of agricultural lands.

The New Urban and Suburban Landscapes

The New Urban and Suburban Landscapes

Within the past 30 to 35 years, our cityscapes have undergone massive transformations. The impact of suburbanization and decentralization has led to edge cities, while in older downtown areas, we have seen that gentrification, redevelopment, and immigration have also created novel urban forms. What we see in today’s cityscapes, then, is a new urban landscape, composed of distinctive elements that we now will discuss.

Shopping Malls

Shopping Malls Many people consider the image of the shopping mall, surrounded by mass-produced suburbs, to be one of the most distinctive landscape symbols of modern urbanity. Yet, oddly, most malls are not designed to be seen from the outside. As a matter of fact, without appropriate signs, a passerby could proceed past a mall without noticing any visual display. Unlike the retail districts of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century cities, where grand architectural displays along major boulevards were the norm, shopping malls are enclosed, private worlds that are meant to be seen from the inside. Often located near an off-ramp of a major freeway or beltway of a metropolitan area and close to the middle- and upper-class residential neighborhoods, shopping malls can be distinguished more by their extensive parking lots than by their architectural design.

For all that, shopping malls do have a characteristic form. The early malls of the 1960s tended to have a simple, linear form, with department stores at both ends that functioned as anchors and 20 to 30 smaller shops connecting the two ends. In the 1970s and 1980s, much larger malls were built, and their form became more complex.

Malls today are often several stories high and may contain five or six anchor stores and up to 400 smaller shops. In addition, many malls now serve more than a retail function—they often contain food courts and restaurants, professional offices, movie complexes, hotels, chapels, and amusement arcades and centers. A shopping center in Kuala Lumpur, known simply as The Mall, contains Malaysia’s largest indoor amusement park, a replica of the historic city of Malacca, a cineplex, and a food court, in addition to hundreds of stores. Many scholars consider these megamalls to be the new centers of urban life because they seem to be the major sites for social interaction. For example, after workplace, home, and school, the shopping mall is where most Americans spend their time.

325

However, unlike the open-air marketplaces of an earlier era, shopping malls are private, not public, spaces. The use of the shopping mall as a place for social interaction, therefore, is always of secondary importance to its private, commercial function. If a certain group of people were considered a nuisance to shoppers, the mall owners could prevent them from what Jeffrey Hopkins calls “‘mallingering’—the act of lingering about a mall for economic and noneconomic social purposes.”

Office Parks

office park A cluster of office buildings, usually located along an interstate highway, often forming the nucleus of an edge city.

Office Parks With the connection of metropolitan areas by major interstate highways and with the development of new communication technologies, office buildings no longer have to be located in the central city. Cheaper rent in suburban locations, combined with the convenience of easy-access parking and the privacy of a separate location, has led to the construction of office parks throughout suburban America. Many of these office parks are occupied by the regional or national headquarters of large corporations or by local sales and professional offices. To take advantage of economies of scale, many of these offices will cluster together and rent or buy space from a land development company. These clusters of office buildings are usually located along an interstate highway and often form the nuclei of edge cities.

The use of the word park to identify this new landscape element points to the consciously antiurban imagery of these complexes. Many of these developments are surrounded by a well-landscaped outdoor space, often incorporating artificial lakes and waterfalls (Figure 11.26). Jogging paths, fitness trails, and picnic tables all cater to the new lifestyle of professional and managerial employees.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.29

Why do you rarely find very tall office buildings in the suburbs?

high-tech corridor An area along a limited-access highway that contains offices and other services associated with high-tech industries.

Many office parks are located along what have been called high-tech corridors: areas along a limited-access highway that contain offices and other services associated with high-tech industries. As our discussion of edge cities suggests, this new type of commercial landscape is gradually replacing our downtowns as the workplace for most Americans.

Master-Planned Communities

master-planned community A large-scale residential development that includes, in addition to architecturally compatible housing units, planned recreational facilities, schools, and security measures.

Master-Planned Communities Many newer residential developments on the suburban fringe are planned and built as complete neighborhoods by private development companies. These master-planned communities include not only architecturally compatible housing units but also recreational facilities (such as tennis courts, fitness centers, bike paths, and swimming pools), schools, and security measures (gated or guarded entrances). In Weston, a master-planned community that covers approximately 10,000 acres (4000 hectares) in southern Florida, land use is completely regulated not only within the gated residential complexes but also along the road system that connects Weston to the interstate highway. Shrubbery is planted strategically to shield residents from views of the roadway, and the road signs are uniform in style and encased in stylish gray weathered-wood frames. This massive community—Weston is now home to 50,000 people—contains various complexes catering to particular lifestyles, ranging from smaller patio homes to equestrian estates. In the mid-1990s, homes in one such complex—Tequesta Point—cost $250,000 to $300,000 and came with gated entranceways, split-level floor plans, and Roman bathtubs. Those in Bermuda Springs, on the other hand, which originally cost $115,000 to $120,000, were significantly smaller and did not offer the same interior features. Typical of master-planned communities, the name of the development itself was chosen to convey a hometown feeling. Developers carried out an extensive marketing survey before they settled on the name Weston.

326

Festival Settings

festival setting A multiuse redevelopment project built around a particular setting, often a waterfront or a location with a historical association.

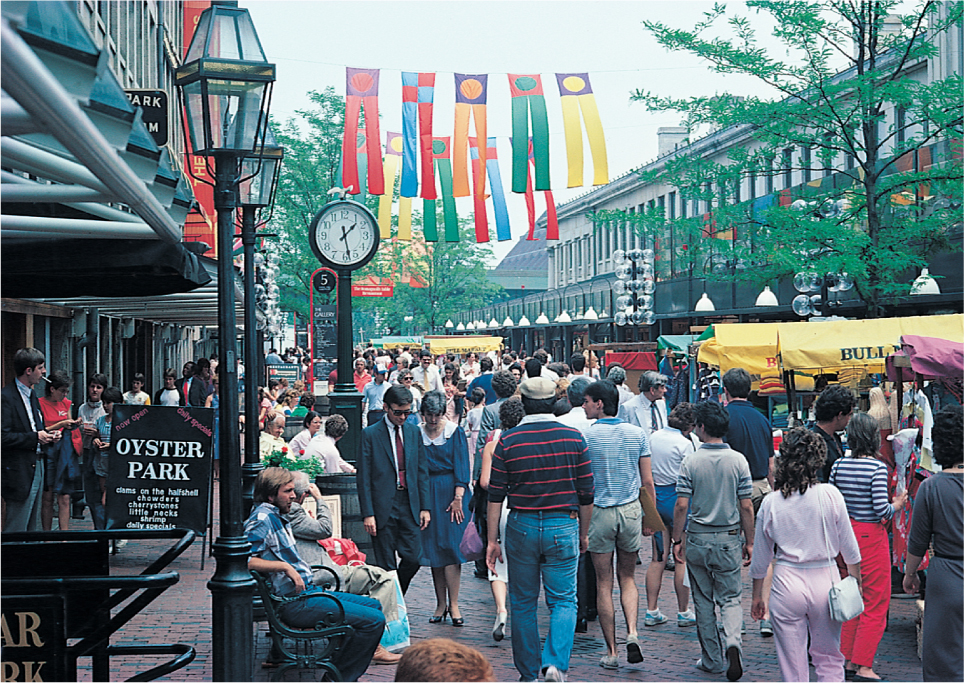

Festival Settings In many cities, gentrification efforts focus on a multiuse redevelopment scheme that is built around a particular setting, often one with a historical association. Waterfronts are commonly chosen as focal points for these large-scale projects, which Paul Knox has referred to as festival settings. These complexes integrate retailing, office, and entertainment facilities and incorporate trendy shops, restaurants, bars and nightclubs, and hotels. Knox suggests that these developments are “distinctive as new landscape elements merely because of their scale and their consequent ability to stage—or merely to be—the spectacular.” Such festival settings as Faneuil Hall in Boston, Bayside in Miami, and Riverwalk in San Antonio serve as sites for concerts, ethnic festivals, and street performances; they also serve as focal points for the more informal human interactions that we usually associate with urban life (Figure 11.27). In this sense, festival settings do perform a vital function in the attempt to revitalize our downtowns. Yet, like many other gentrification efforts, these massive displays of wealth and consumption often stand in direct contrast to neighboring areas of the inner city that have received little, if any, monetary or other social benefit from these projects.

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.30

In what ways do you think this cultural landscape differs from the original Quincy Market in the early nineteenth century?

“Militarized” Space and Gated Communities

“Militarized” Space and Gated Communities Considered together, these new elements in the urban landscape suggest some trends that many scholars find disturbing. Urbanist Mike Davis has called one such trend the “militarization” of urban space, meaning that increasingly space is used to set up defenses against people the city considers undesirable. This includes landscape developments that range from the lack of street furniture to guard against the homeless living on the streets to gated and guarded residential communities (Figure 11.28) to the complete segregation of classes and “races” within the city. Particularly in downtown redevelopment schemes, the goal of city planners and others is usually to provide safe and homogeneous environments, segregated from the diversity of cultures and lifestyles that often characterizes the central area of most cities. As Davis says, “Cities of all sizes are rushing to apply and profit from a formula that links together clustered development, social homogeneity, and a perception of security.” Although this “militarization” is not completely new, it has taken on epic proportions as whole sections of such cities as Los Angeles, Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Miami have become “militarized” spaces (Figure 11.29).

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.31

Why does this community look from the outside so similar to what you would see in a North American city?

Thinking Geographically

Question 11.32

Does this seem like a welcoming space? Should it be?

327

Decline of Public Space

Decline of Public Space Related to the increase in “militarized” space is the decline of public spaces in most of our cities. For example, the change in shopping patterns from the downtown retailing area to the suburbs indicates a change of emphasis from the public space of city streets to the privately controlled and operated shopping malls. Similarly, many city governments, often joined by private developers, have built enclosed walkways either above or below the city streets. These walkways serve partly to provide a climate-controlled means of passing from one building to another and partly to provide pedestrians with a “safe” environment that avoids possible confrontations on the street. Again, the public space of the street is being replaced by controlled spaces that do not provide the same access to all members of the urban community. It remains to be seen whether this trend will continue or whether new public spaces will accommodate all groups of people within the urban landscape.

328