What is Cultural Geography?

What is Cultural Geography?

As its name implies, cultural geography forms one part of the discipline of geography, complementing physical geography, the part of the discipline that deals with the natural environment. To understand the scope of cultural geography, we must first agree on the meaning of culture.

culture A total way of life held in common by a group of people, including such learned features as speech, ideology, behavior, livelihood, technology, and government; or the local, customary way of doing things—a way of life; an ever-changing process in which a group is actively engaged; a dynamic mix of symbols, beliefs, speech, and practices.

Many definitions of culture exist, some broad and some narrow. We might best define culture as learned collective human behavior, as opposed to instinctive, or inborn, behavior. These learned traits form a way of life held in common by a group of people. Learned similarities in speech, behavior, ideology, livelihood, technology, value system, and society bind people together. Culture involves a communication system of acquired beliefs, memories, perceptions, traditions, and attitudes that serve to supplement and channel instinctive behavior. In short, as geographer Yi-Fu Tuan has said, culture is the “local, customary way of doing things; geographers write about ways of life.”

A particular culture is not a static, fixed phenomenon, and it does not always govern its members. Rather, as geographers Kay Anderson and Fay Gale put it, “culture is a process in which people are actively engaged.” Individual members can and do change a culture, which means that ways of life constantly change and that tensions between opposing views are usually present. Cultures are never internally homogeneous because individual humans never think or behave in exactly the same manner.

3

cultural geography The study of spatial variations among cultural groups and the spatial functioning of society.

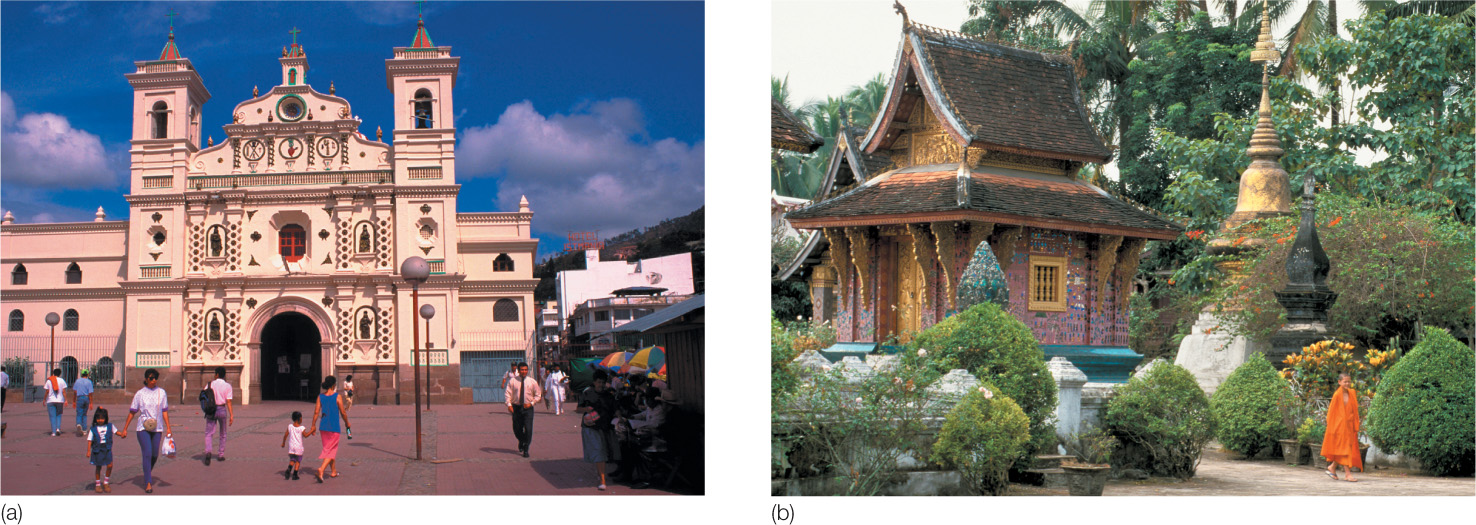

Cultural geography, then, is the study of spatial variations among cultural groups and the spatial functioning of society. It focuses on describing and analyzing the ways language, religion, economy, government, and other cultural phenomena vary or remain constant from one place to another and on explaining how humans function spatially (Figure 1.1). Cultural geography is, at heart, a celebration of human diversity, or as the Russian ethnographer Leo Gumilev wrote, “the study of differences among peoples.”

Thinking Geographically

Question

In what ways are these two structures—one a Catholic church in Honduras (a) and the other a Buddhist temple in Laos (b)—alike and different?

In seeking explanations for cultural diversity and place identity, geographers consider a wide array of factors that cause this diversity. Some of these involve the physical environment: terrain, climate, natural vegetation, wildlife, variations in soil, and the pattern of land and water. Because we cannot understand a culture removed from its physical setting, human geography offers not only a spatial perspective but also an ecological one.

physical environment All aspects of the natural physical surroundings, such as climate, terrain, soils, vegetation, and wildlife.

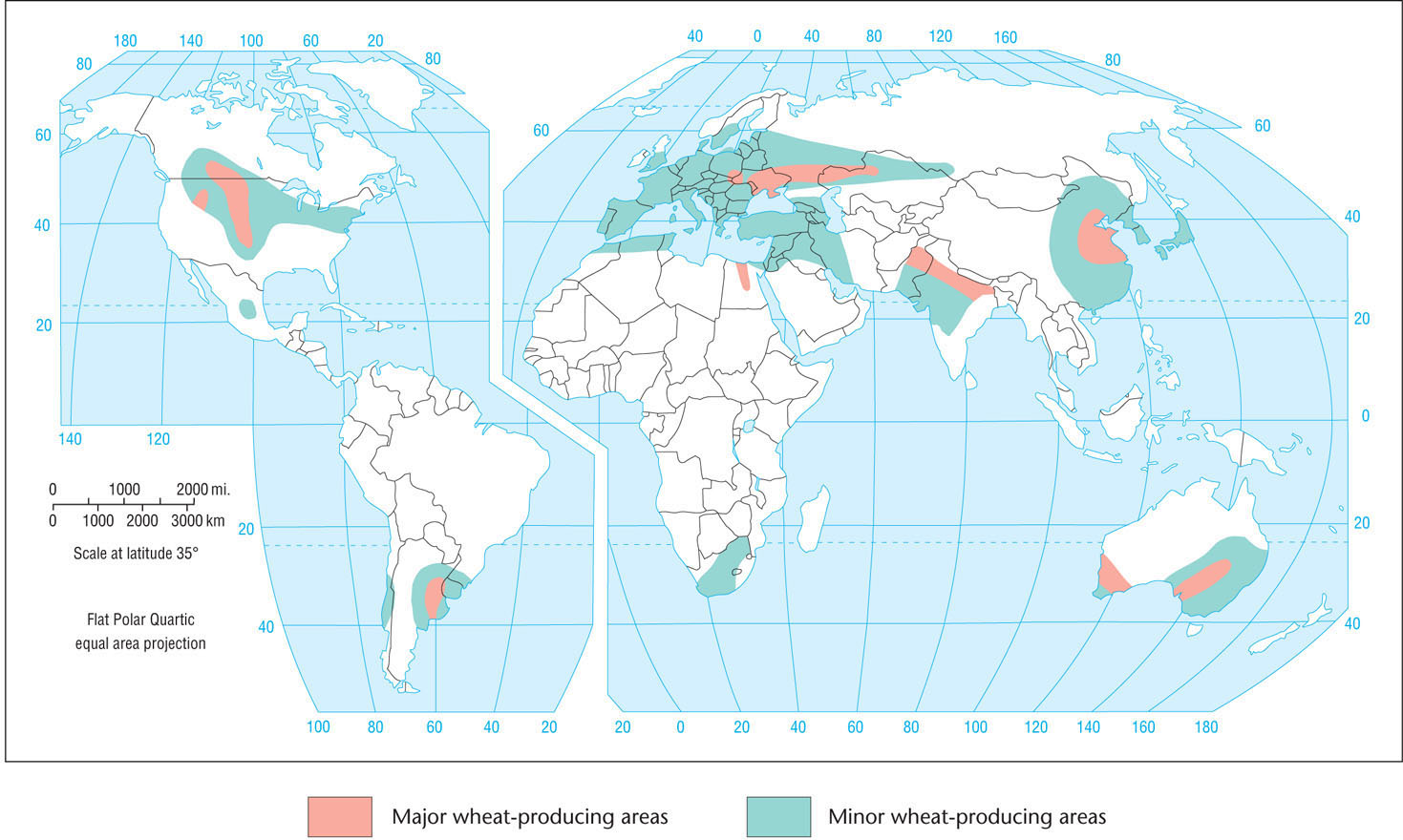

Many complex forces are at work on cultural phenomena, and all of them are interconnected in verycomplicated ways. The complexity of the forces that affect culture can be illustrated by an example drawn from agricultural geo-graphy: the distribution of wheat cultivation in the world. If you look at Figure 1.2, you can see major areas of wheat cultivation in Australia but not in Africa, in the United States but not in Chile, in China but not in Southeast Asia. Why does this spatial pattern exist? Partly it results from environmental factors such as climate, terrain, and soils. Some regions have always been too dry for wheat cultivation. The land in others is too steep or infertile. Indeed, there is a strong correlation between wheat cultivation and midlatitude climates, level terrain, and good soil.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What causal forces might be at work to produce this geographical distribution of wheat farming?

Still, we should not place exclusive importance on such physical factors. People can modify the effects of climate through irrigation; the use of hothouses; or the development of new, specialized strains of wheat. They can conquer slopes by terracing, and they can make poor soils productive with fertilization. For example, farmers in mountainous parts of Greece traditionally wrested an annual harvest of wheat from tiny terraced plots where soil had been trapped behind hand-built stone retaining walls. Even in the United States, environmental factors alone cannot explain the fact that major wheat cultivation is concentrated in the semiarid Great Plains, some distance from states such as Ohio and Illinois, where the climate for growing wheat is better. The cultural geographer knows that wheat has to survive in a cultural environment as well as a physical one.

4

Ultimately, agricultural patterns cannot be explained by the characteristics of the land and climate alone. Many factors complicate the distribution of wheat, including people’s tastes and traditions. Food preferences and taboos, often backed by religious beliefs, strongly influence the choice of crops to plant. Where wheat bread is preferred, people are willing to put great efforts into overcoming physical surroundings hostile to growing wheat. They have even created new strains of wheat, thereby decreasing the environment’s influence on the distribution of wheat cultivation. Other factors, such as public policies, can also encourage or discourage wheat cultivation. For example, tariffs (taxes on foreign products) protect the wheat farmers of France and other European countries from competition with more efficient American and Canadian producers.

This is by no means a complete list of the forces that affect the geographical distribution of wheat cultivation. The distribution of all cultural elements is a result of the constant interplay of diverse factors. Cultural geography is the discipline that seeks such explanations and understandings.