Cultural Ecology

Cultural Ecology

Cultural geographers look on people and nature as interacting. Cultures do not exist in an environmental vacuum; each human group occupies a piece of the physical earth and develops in a specific natural habitat. The cultural geographer must study the interaction between culture and environment in order to understand spatial variations in culture. This is the study of cultural ecology.

The term ecology was coined in the nineteenth century to refer to a new biological science concerned with studying the complex relationships among living organisms and their physical environments. Two influential geographers who applied the study of these relationships to the field of geography were Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904) of Germany and Paul Vidal de La Blache (1845–1918) of France. Ratzel trained in the natural sciences and applied ideas from those disciplines to his geographic theories. In his most notable works, Anthropogeographie (1882) and Politische Geographie (1897), Ratzel advanced the idea that states are like living organisms that expand over the earth with the objective of acquiring “living space” or lebensraum. Ratzel went on to theorize that because states are organic and growing, any state’s current borders are only temporary, and the expansion of these borders reflects the health of that state.

At the time of Ratzel’s writings in Germany, Vidal was already a major force in French geographic thought. Vidal believed that Ratzel’s view of states as living organisms was overstated and believed, instead, that they only “resemble living things.” He also warned that Ratzel’s ideas concerning the expansion of states could lead to dangerous political pressures being placed on the field of geography from outside the discipline. Therefore, he recommended that geographers not adopt a preexisting model of states and territory (as suggested by Ratzel) but rather approach the study of human interactions with the earth with an open mind to include other types of political entities.

cultural ecology Broadly defined, the study of the relationships between the physical environment and culture; narrowly (and more commonly) defined, the study of culture as an adaptive system that facilitates human adaptation to nature and environmental change.

ecosystem A territorially bounded system consisting of interaction between organic and inorganic components.

Because of the writings of Ratzel and Vidal (as well as other geographers of the time), the idea that geography should concern itself with the study of relationships between humans and their physical environment continued to grow in popularity into the early twentieth century. As a result, by the mid-twentieth century, geographers began to join the term ecology with the term culture in order to delineate a new field of study, cultural ecology. Later, another concept, the ecosystem, was introduced to describe a territorially bounded system consisting of interacting organic and inorganic components. Plant and animal species were said to be adapted to specific conditions in the ecosystem and functioned to help keep the system stable over time. Thus cultural ecology today is the study of (1) environmental influences on culture and (2) the impact of people, acting through their culture, on an ecosystem.

cultural adaptation The adaptation of humans and cultures to the challenges posed by the physical environment.

adaptive strategy The unique way in which each culture uses its particular physical environment; those aspects of culture that serve to provide the necessities of life—food, clothing, shelter, and defense.

Cultural ecology implies a two-way street, with people and the environment/ecosystem exerting influence on one another. Put differently, cultural ecology is based on the premise that culture is the human method of meeting physical environmental challenges—that culture is an adaptive system. The term cultural adaptation is used in this context. This outlook borrows heavily from the biological sciences, with the assumption that plant and animal adaptations are relevant to the study of humans. Culture serves to facilitate long-term successful nongenetic human adaptation to nature and environmental change. Adaptive strategy involves those aspects of culture that serve to provide the necessities of life—food, clothing, shelter, and defense. No two cultures employ the same strategy, even within the same physical environment. Such strategies involve culturally transmitted, or learned, behavior that permits a population to survive in its natural environment.

Through the years, human geographers have developed various perspectives on the interaction between humans and the land. Four schools of thought have developed: environmental determinism, possibilism, environmental perception, and humans as modifiers of the Earth.

Environmental Determinism

environmental determinism The belief that cultures are directly or indirectly shaped by the physical environment.

Environmental Determinism During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many geographers accepted environmental determinism, the belief that the physical environment is the dominant force shaping cultures and that humankind is essentially a passive product of its physical surroundings. Humans are clay to be molded by nature. Similar physical environments produce similar cultures.

For example, environmental determinists believed that peoples of the mountains were predestined by the rugged terrain to be simple, backward, conservative, unimaginative, and freedom loving. Dwellers in the desert were likely to believe in one God but to live under the rule of tyrants. Temperate climates produced inventiveness, industriousness, and democracy. Coastlands pitted with fjords produced great navigators and fishers. Environmental determinism had serious consequences, particularly during the time of European colonization in the late nineteenth century. For example, many Europeans saw Latin American native inhabitants as lazy, childlike, and prone to vices such as alcoholism because of the tropical climates that cover much of this region. Living in a tropical climate supposedly ensured that people didn’t have to work very hard for their food. Europeans were able to rationalize their colonization of large portions of the world in part along climatic lines. Because the natives were “naturally” lazy and slow, the European reasoning went, the natives would benefit from the presence of the “naturally” stronger, smarter, and more industrious Europeans who came from more temperate lands.

Determinists overemphasize the role of environment in human affairs. This does not mean that environmental influences are inconsequential or that geographers should not study such influences. Rather, the physical environment is only one of many forces affecting human culture and is never the sole determinant of behavior and beliefs.

Possibilism

possibilism A school of thought based on the belief that humans, rather than the physical environment, are the primary active force; that any environment offers a number of possible ways for a culture to develop; and that the choices among these possibilities are guided by cultural heritage.

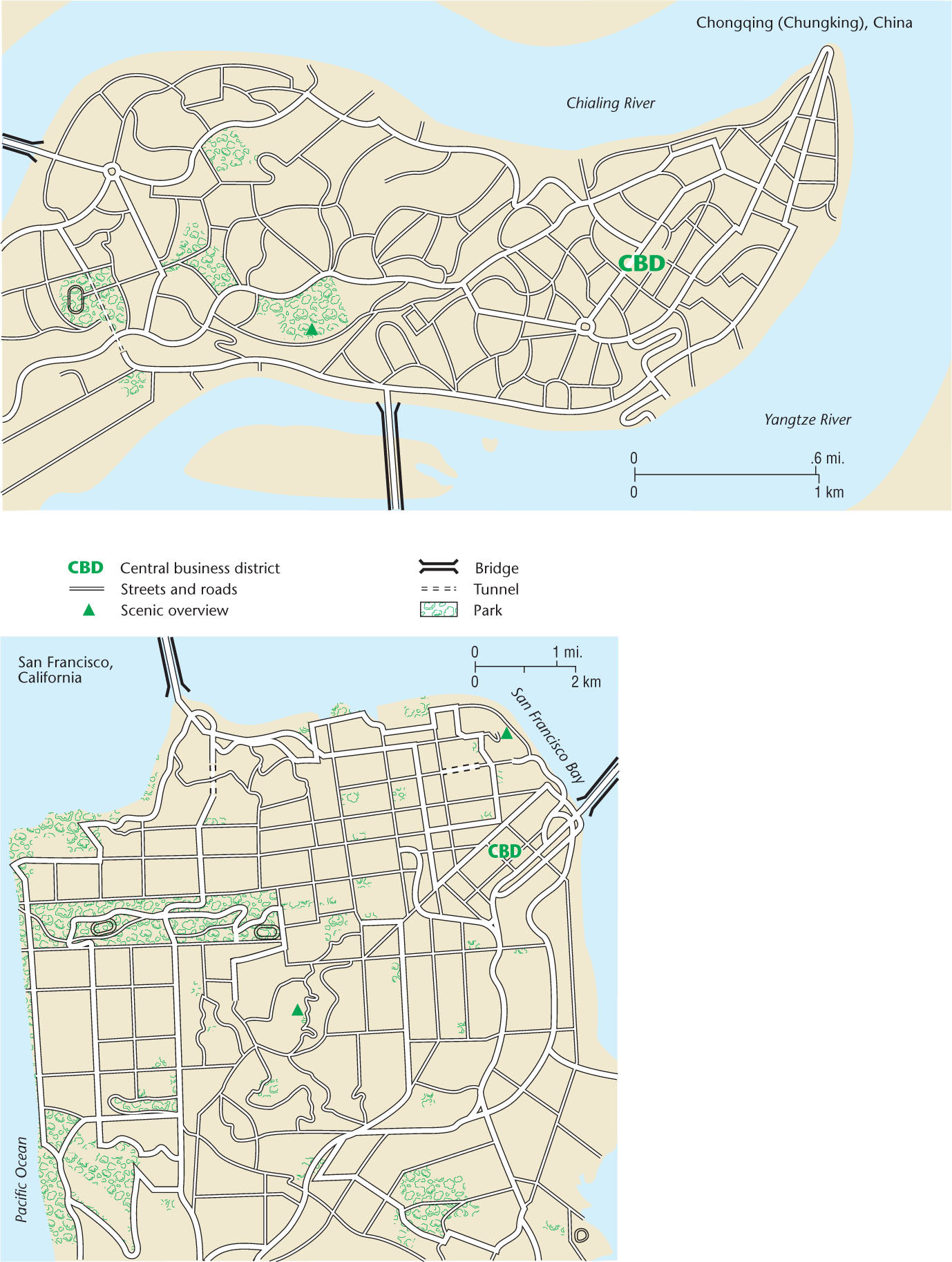

Possibilism Since the 1920s, possibilism has been the favored view among geographers. Possibilists claim that any physical environment offers a number of possible ways for a culture to develop. In this way, the local environment helps shape its resident culture. However, a culture’s way of life ultimately depends on the choices people make among the possibilities that are offered by the environment. These choices are guided by cultural heritage and are shaped by a particular political and economic system. Possibilists see the physical environment as offering opportunities and limitations; people make choices among these to satisfy their needs. Figure 1.14 provides an interesting example: the cities of San Francisco and Chongqing both were built on similar physical terrains that dictated an overall form, but differing cultures led to very different street patterns, architecture, and land use. In short, local traits of culture and economy are the products of culturally based decisions made within the limits of possibilities offered by the environment.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What do these contrasts suggest about the relative merits of environmental determinism and possibilism? About the role of culture?

Most possibilists think that the higher the technological level of a culture, the greater the number of possibilities and the weaker the influences of the physical environment. Technologically advanced cultures, in this view, have achieved some mastery over their physical surroundings. Geographers Jim Norwine and Thomas Anderson, however, warn that even in these advanced societies “the quantity and quality of human life are still strongly influenced by the natural environment,” especially climate. They argue that humankind’s control of nature is anything but supreme and perhaps even illusory. One only has to think of the devastation caused by the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and the 2011 Japanese earthquake and tsunami to underscore the often-illusory character of the control humans think they have over their physical surroundings.

18

19

Environmental Perception

environmental perception The belief that culture depends more on what people perceive the environment to be than on the actual character of the environment; perception, in turn, is colored by the teachings of culture.

Environmental Perception Another approach to cultural ecology focuses on how humans perceive nature. Each person and cultural group has mental images of the physical environment, shaped by knowledge, ignorance, experience, values, and emotions. To describe such mental images, cultural geographers use the term environmental perception. Whereas the possibilist sees humankind as having a choice of possibilities in a given physical setting, the environmental perceptionist declares that the choices people make will depend more on what they perceive the environment to be than on the actual character of the land. Perception, in turn, is colored by the teachings of culture.

natural hazard Inherent danger present in a given habitat, such as flooding, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, or earthquakes; often perceived differently by different peoples.

Some of the most productive research done by environmental perceptionists has been on the topic of natural hazards, such as flooding, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, insect infestations, and droughts. All cultures react to such hazards and catastrophes, but the reactions vary greatly from one group to another. Some people reason that natural disasters and risks are unavoidable acts of the gods, perhaps even divine retribution. Often they seek to cope with the hazards by placating their gods. Others hold government responsible for taking care of them when hazards yield disasters. Many cultural groups living in industrialized states view natural hazards as problems that can be solved by technological means. A common manifestation of this belief has been the widespread construction of dams, levees, and sea walls to prevent flooding. However, history shows that these measures do not always ensure protection. For example, during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, numerous dams and levees in the New Orleans area failed and more than 1800 people lost their lives. Tens of thousands of people were left homeless, and the city has still not fully recovered.

In 2011, another natural disaster demonstrated that human attempts to provide technological safeguards against environmental forces do not always succeed. A magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit Japan, causing a devastating tsunami with up to 49-foot waves. The tsunami crushed sea walls and other built defenses, flooding thousands of roadways and destroying countless homes, schools, and commercial buildings. Figure 1.15 shows an example of this devastation in Otsuchi, a small coastal town. Immediately following the tsunami, 12,000 of the town’s 15,000 inhabitants were either dead or reported missing. Despite early warning systems in place, these (and other) Japanese residents had only 8 to 10 minutes to attempt escape before the wave hit. Region-wide, over 20,000 people died or were reported missing and presumed dead after the disaster. The earthquake and tsunami also did unprecedented damage to infrastructure, including airports, rail lines, and shipping ports. At the Fukushima nuclear facility, two reactors exploded and radiation leaked out, necessitating the evacuation of thousands of residents living near the facility. The massive loss of life, staggering damage to the built environment, and serious nuclear accident resulting from the Japanese earthquake and tsunami caused many other states to question their technological capabilities in the face of natural disasters.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How do you think the experiences of people surviving the 2011 Japanese disaster will affect their perceptions of the physical environment?

20

organic view of nature The view that humans are part of, not separate from, nature and that the habitat possesses a soul and is filled with nature-spirits.

mechanistic view of nature The view that humans are separate from nature and hold dominion over it and that the habitat is an integrated mechanism governed by external forces that the human mind can understand and manipulate.

In virtually all cultures, people knowingly inhabit hazard zones, especially floodplains, exposed coastal sites, drought-prone regions, and the environs of active volcanoes. More Americans than ever now live in areas likely to be devastated by hurricanes along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico and atop earthquake faults in California. How accurately do they perceive the hazard involved? Why have they chosen to live there? How might we minimize the eventual disasters? The cultural geographer seeks the answers to such questions and aspires, with other geographers, to mitigate the inevitable disasters through such devices as land-use planning.

Perhaps the most fundamental expression of environmental perception lies in the way different cultures see nature itself. Nature is a culturally derived concept that has different meanings to different peoples. In the organic view, held by many traditional groups, people are part of nature. The habitat possesses a soul, is filled with nature-spirits, and must not be offended. By contrast, most Western peoples believe in the mechanistic view of nature. Humans are separate from and hold dominion over nature. They see the habitat as an integrated system of mechanisms governed by external forces that can be rendered into natural laws and understood by the human mind.

Humans as Modifiers of the Earth

Humans as Modifiers of the Earth Many cultural geographers, observing the environmental changes people have wrought, emphasize humans as modifiers of the habitat. This presents yet another facet of cultural ecology. In a sense, the humans-as-modifier school of thought is the opposite of environmental determinism. Whereas the determinists proclaim that nature molds humankind and possibilists believe that nature presents possibilities for people, geographers who study the human impact on the land assert that humans mold nature (Figure 1.16).

Thinking Geographically

Question

How can we adopt less destructive ways of modifying the land?

In addition to the deliberate modifications of the Earth through such activities as mining, logging, and irrigation, we now know that even seemingly innocuous behavior, repeated for millennia, for centuries, or in some cases for mere decades, can have catastrophic effects on the environment. Plowing fields and grazing livestock can eventually denude regions. The increasing release of fossil-fuel emissions from vehicles and factories—what are known as greenhouse gases—is arguably leading to global warming, with potentially devastating effects on Earth’s environment. Clearly, access to energy and technology is the key variable that controls the magnitude and speed of environmental alteration. Geographers seek to understand and explain the processes of environmental alteration as they vary from one culture to another and, through applied geography, to propose alternative, less destructive modes of behavior.

Cultural geographers began to concentrate on the human role in changing the face of Earth long before the present level of ecological consciousness developed. They learned early on that different cultural groups have widely different outlooks on humankind’s role in changing Earth. Some, such as those rooted in the mechanistic tradition, tend to regard environmental modification as divinely approved, viewing humans as God’s helpers in completing the task of creation. Other groups, organic in their view of nature, are much more cautious, taking care not to offend the forces of nature. They see humans as part of nature, meant to be in harmony with their environment.