Cultural Interaction

Cultural Interaction

cultural interaction The relationship of various elements within a culture.

The relationship between people and the land, the theme of cultural ecology, lies at the heart of traditional geography. However, the explanation of human spatial variations also requires consideration of a whole range of cultural and economic factors. The cultural geographer recognizes that all facets of culture are systematically and spatially intertwined or integrated. In short, cultures are complex wholes rather than series of unrelated traits. They form integrated systems in which the parts fit together causally. All aspects of culture are functionally interdependent on one another. The theme of cultural interaction addresses this complexity. Cultural interaction recognizes that (1) the immediate causes of some cultural phenomena are other cultural phenomena and (2) a change in one element of culture requires an accommodating change in others.

21

For example, religious belief has the potential to influence a group’s voting behavior, diet, shopping patterns, type of employment, and social standing. Traditional Hinduism, the majority religion of India, segregates people into social classes called castes and specifies what forms of livelihood are appropriate for each. The Mormon faith forbids the consumption of alcoholic beverages, tobacco, and caffeine, thereby influencing both the diet and shopping patterns of its members.

Geographers have employed two fundamentally different approaches to studying cultural interaction: the scientific and the humanistic.

Social Science

space A term used to connote the objective, quantitative, theoretical, model-based, economics-oriented type of geography that seeks to understand spatial systems and networks through application of the principles of social science.

model An abstraction, an imaginary situation, proposed by geographers to simulate laboratory conditions so that they may isolate certain causal forces for detailed study.

Social Science Those who view cultural geography as a social science, also called “modernists,” believe that we should apply the scientific method to the study of people. Emulating physicists and chemists, they devise theories and seek regularities or universal spatial principles that cut across cultural lines to govern all of humankind. These principles ideally become the basis for laws of human spatial behavior. Space is the word that perhaps best connotes this scientific approach to cultural geography.

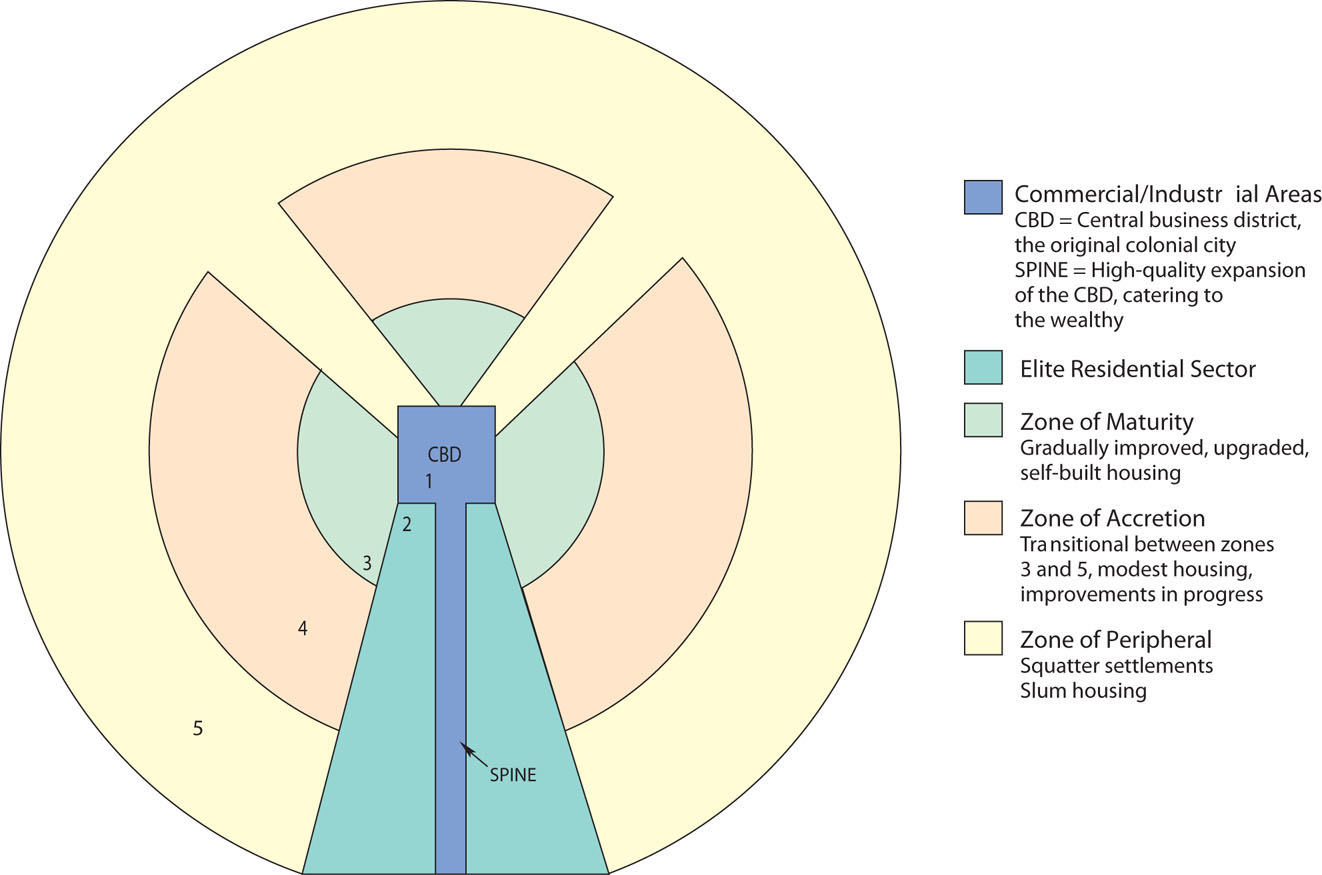

Social scientists face several difficulties. First, they tend to overemphasize economic factors at the expense of culture. Second, they have no laboratories in which to test their theories. They cannot run controlled experiments in which certain forces can be neutralized so that others can be studied. Their response to this deficiency is a technique known as model building. Aware that in the real world many causal forces are involved, they set up artificial model situations in order to focus on one or several potential factors. Figure 1.17 is an example of a model. Throughout Fundamentals of The Human Mosaic, we will see many of the classic models built by cultural geographers.

Thinking Geographically

Question

In what ways would this model not be applicable to cities in the United States and Canada?

22

Some culture-specific models are particularly sensitive to cultural variables. Such models still seek regularities and spatial principles but do so relatively modestly within the bounds of individual cultures. For example, several geographers proposed a model for Latin American cities in an effort to stress similarities among them and to understand underlying causal forces (Figure 1.17). No actual city in Latin America conforms precisely to this model. Instead, the model is deliberately simplified and generalized so that Latin American cities can be better understood. This model will look strange to a person living in a city in the United States or Canada, for it describes a very different kind of urban environment based in another culture.

Humanistic Geography

place A term used to connote the subjective, humanistic, culturally oriented type of geography that seeks to understand the unique character of individual regions and places, rejecting the principles of science as flawed and unknowingly biased.

topophilia Love of place; used to describe people who exhibit a strong sense of place.

Humanistic Geography If the social scientist seeks to level the differences among people in the quest for universal explanations, the humanistic geographer celebrates the uniqueness of each region and place. Place is the key word connoting a humanistic approach to geography. In fact, the humanistic geographer Yi-Fu Tuan even coined the word topophilia, literally “love of place,” to describe people who exhibit a strong sense of place and the geographers who are attracted to the study of such places and peoples. Geographer Edward Relph tells us that “to be human is to have and know your place” in the geographical sense. To the humanist, cultural geography is an art rather than a science.

Traditional humanists in geography are as concerned with explanation as the social scientists, but they seek to explain unique phenomena—place and region—rather than seeking universal spatial laws. Indeed, most humanists doubt that laws of spatial behavior even exist. They believe in a far more chaotic world than the scientist could tolerate.

The debate between scientists and humanists is both healthy and necessary. The two groups ask different questions about place and space; not surprisingly, they obtain different answers. Both lines of inquiry yield valuable findings. In Fundamentals of The Human Mosaic, we present both sides of the scientist versus humanist debate within the theme of cultural interaction.