Cultural Landscape

Cultural Landscape

cultural landscape The artificial landscape; the visible human imprint on the land.

What are the visible expressions of culture? How are peoples’ interactions with nature materially expressed? What do regions actually look like? These questions provide the basis of our fifth and final theme, cultural landscape.

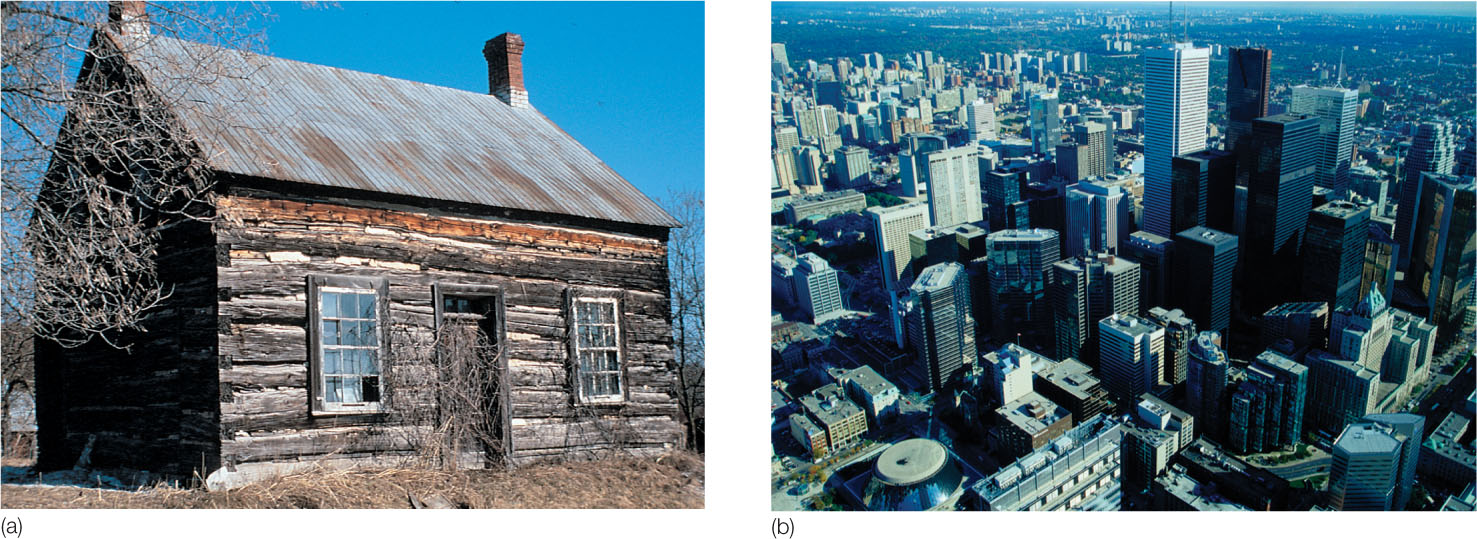

The human or cultural landscape is composed of all the built forms that cultural groups create in inhabiting Earth—roads, agricultural fields, cities, houses, parks, gardens, commercial buildings, and so on. Every inhabited area has a cultural landscape, fashioned from the natural landscape, and each uniquely reflects the culture or cultures that created it (Figure 1.18). Landscape mirrors a culture’s needs, values, and attitudes toward Earth, and the cultural geographer can learn much about a group of people by carefully observing and studying the landscape. Indeed, so important is this visual record of cultures that some geographers regard landscape study as geography’s central interest.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why is rice cultivated in such hilly areas in Asia, while in the United States rice farming is confined to flat plains?

23

Why is such importance attached to the human landscape? Perhaps part of the answer is that it visually reflects the most basic strivings of humankind: shelter, food, and clothing. In addition, the cultural landscape reveals people’s different attitudes toward the modifications of Earth. It also contains valuable evidence about the origin, spread, and development of cultures because it usually preserves various types of archaic forms. Dominant and alternative cultures use, alter, and manipulate landscapes to express their diverse identities.

Aside from containing archaic forms, landscapes also convey revealing messages about the present-day inhabitants and cultures. According to geographer Pierce Lewis, “The cultural landscape is our collective and revealing autobiography, reflecting our tastes, values, aspirations, and fears in tangible forms.” Cultural landscapes offer “texts” that geographers read to discover dominant ideas and prevailing practices within a culture, as well as less dominant and alternative forms within that culture. This reading, however, is often a very difficult task, given the complexity of cultures, cultural change, and recent globalizing trends that can obscure local histories.

Lewis attempted to simplify the reading of cultural landscapes by devising a set of five axioms (or rules) with a number of associated corollaries (something that naturally follows a stated rule). One such axiom in Lewis’s work is the axiom of landscape as a clue to culture. This axiom states that cultural landscapes provide strong evidence of the people who live there and their history. In the regional corollary to this rule, Lewis states the following: If one region looks substantially different from another region, it is likely that the cultures of the two places are also different. Figure 1.19a shows French street names on signs in Montréal, Québec, reflecting the region’s early settlement by the French as well as its contemporary use of the French language. Figure 1.19b, in contrast, reflects a settlement history dominated by the British and the use of the English language in Canada’s British Columbia region. These clues to reading the cultural landscapes in these two regions of Canada lead us to investigate other cultural differences that may exist between them.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What other examples of regional differences in the cultural landscape may provide clues to differences in cultural influence on those regions?

Reflecting on Geography

Question

As we will learn throughout this book, landscapes are often created from more than one set of cultural values and beliefs, which are often in conflict with one another. How then can we read conflict into the landscape, when it appears so natural and unified? What sort of information would we need?

24

Since the time of Lewis’s groundbreaking work in the 1970s, geographers have pushed the idea of reading the landscape further in order to focus on the symbolic and ideological qualities of landscape. In fact, as geographer Denis Cosgrove has suggested, the very idea of landscape itself was ideological, in that its development in the Renaissance served the interests of the new elite class for whom agricultural land was valued not for its productivity but for its use as a visual subject. Land, in other words, was important to look at as a scene, and the actual workings that were necessary for agriculture were thus hidden from these views. If you go to an art museum, for example, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to find in the Italian Renaissance room any landscape paintings that depict agricultural laborers.

symbolic landscape Landscape that express the values, beliefs, and meanings of a particular culture.

Closer to home, we need only look outside our windows to see other symbolic and ideological landscapes. One of the most familiar and obvious symbolic landscapes is the urban skyline. Composed of tall buildings, many of which house financial service industries, it represents the power and dominance of finance and economics within that culture (Figure 1.20). However, other cities are dominated by tall structures that have little to do with economics but more with religion. In medieval Europe, for example, cathedrals and churches rose high above other buildings, symbolizing the centrality and dominance of Roman Catholicism in this culture.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What landscape form best symbolizes your town or city?

Even the most mundane landscape element can be interpreted as symbolic. The typical middle-class suburban American or Canadian home, for example, can be interpreted as an expression of a dominant set of ideas about culture and family structure (Figure 1.21). These homes are often composed of a living room, dining room, kitchen, and bedrooms, all separated by walls. The cultural assumptions built into this division of space include the assumed value of individual privacy (everyone has his or her own bedroom); the idea that certain functions should be spatially separate from others (cooking, eating, socializing, sleeping); and the notion that a family is composed of a mother, father, and children (indicated by the “master” bedroom and smaller children’s bedrooms). Thus, even the most common of landscapes can be seen as symbolic of a particular culture.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Can you think of other countries where ranch houses are common?

25

Aspects of the Cultural Landscape

settlement form The spatial arrangement of buildings, roads, towns, and other features that people construct while inhabiting an area.

nucleation A settlement form characterized by density.

dispersed A settlement form in which people live relatively distant from one another.

Aspects of the Cultural Landscape As we have seen, the physical content of the cultural landscape is both varied and complex. To better study and understand these complexities, geographical studies focus on three principal aspects of landscape: settlement forms, land-division patterns, and architectural styles.

In the study of settlement forms, geographers describe and explain the spatial arrangement of buildings, roads, and other features that people construct while inhabiting an area. One of the basic ways in which geographers categorize settlement forms is to examine their degree of nucleation, or the relative density of landscape elements. Urban centers are of course very nucleated, whereas rural farming areas tend to be much less nucleated, what geographers call dispersed. Another common way to think about settlement forms is the degree to which they appear standardized and planned, such as the grid form of much of the American West (Figure 1.22), versus the degree to which the forms appear to be organic (that is, to have been built without any apparent geometric plan), such as the central areas of most European cities. Thinking about settlement forms in terms of these two basic categories helps geographers begin their analysis of the relationships between cultures and the landscapes they produce.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why do you think geometric patterns dominate the western United States?

land-division pattern The spatial pattern of various types of land use.

Land-division patterns indicate the uses of particular parcels of land and reveal the way people have divided the land for economic, social, and political uses. Within a particular nucleated settlement form—a city, for example—you can see different patterns of land use. Some areas are devoted to economic uses, others to residential, political (city hall, for example), social, and cultural uses. Each of these areas can be further divided. Economic uses can include offices for financial services, retail stores, warehouses, and factories. Residential areas are often divided into middle-class, upper-class, and working-class districts and/or are grouped by ethnicity and race (see chapter 11). Such patterns, of course, vary a great deal from place to place and culture to culture, as we will see throughout this book. One of the best ways to glimpse settlement and land-division patterns is through an airplane window. Looking down, you can see the multicolored abstract patterns of planted fields, as vivid as any modern painting, and the regular checkerboard or chaotic tangle of urban streets.

26

architectural style The exterior and interior designs and layouts of the cultural and physical landscape.

Perhaps no other aspect of the human landscape is as readily visible from ground level as the architectural style of a culture. Geographers look at the exterior materials and decoration, as well as the layout and design of the interiors. Styles tend to vary both through time, as cultures change, and across space, in the sense that different cultures adopt and invent their own stylistic detailing according to their own particular needs, aesthetics, and desires. Thus, examining architectural style is often useful when trying to date a particular landscape element or when trying to understand the particular values and beliefs that cultures may hold. In North American culture, different building styles catch the eye: modest white New England churches and giant urban cathedrals, hand-hewn barns and geodesic domes, wooden one-room schoolhouses and the new windowless school buildings of urban areas, shopping malls and glass office buildings. Each tells us something about the people who designed, built, or inhabit these spaces. Thus, architecture provides a vivid record of the resident culture (Figure 1.23). For this reason, cultural geographers have traditionally devoted considerable attention to examining architecture and style in the cultural landscape.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What conclusion might a perceptive person from another culture reach (considering the “virtues” of height, durability, and centrality) about the ideology of the culture that produced the Toronto landscape?