Many Cultures: Material, Nonmaterial, Folk, Popular, and Mass

Many Cultures: Material, Nonmaterial, Folk, Popular, and Mass

material culture All physical, tangible objects made and used by members of a cultural group. Examples are clothing, buildings, tools and utensils, musical instruments, furniture, and artwork; the visible aspect of culture.

nonmaterial culture The wide variety of tales, songs, lore, beliefs, superstitions, and customs that pass from generation to generation as part of an oral or written tradition.

Cultures are classified using many different criteria. The concept of culture includes both material and nonmaterial elements. Material culture includes all objects or things made and used by members of a cultural group: buildings, furniture, clothing, artwork, musical instruments, and other physical objects. The elements of material culture are visible. Nonmaterial culture includes the wide range of beliefs, values, myths, and symbolic meanings that are transmitted across generations of a given society. Cultures may be categorized and geographically located using criteria based on either or both of these features.

Let’s explore how these criteria are used to identify, categorize, and graphically delineate cultures. According to literary critic and cultural theorist Raymond Williams, culture is one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, people began to speak of “cultures” in the plural form. Specifically, they began thinking about “European culture” in relation to other cultures around the world. As Europe industrialized and urbanized in the nineteenth century, a new term, folk culture, was invented to distinguish traditional ways of life in rural spaces from new urban, industrial ones. Thus, folk culture was defined and made sense only in relation to an urban, industrialized culture. Urban dwellers began to think—in increasingly romantic and nostalgic terms—of rural spaces as inhabited by distinct folk cultures.

folk Traditional, rural; the opposite of “popular.”

folk culture Small, cohesive, stable, isolated, nearly self-sufficient group that are homogeneous in custom and ethnicity; characterized by a strong family or clan structure, order maintained through sanctions based in the religion or family, little division of labor other than that between the sexes, frequent and strong interpersonal relationships, and material cultures consisting mainly of handmade goods.

folk geography The study of the spatial patterns and ecology of traditional groups.

The word folk describes a rural people who live in an old-fashioned way—a people holding onto a lifestyle relatively little influenced by modern technology. Folk cultures are small, rural, cohesive, conservative, isolated, largely self-sufficient groups that are homogeneous in custom and ethnicity. In terms of nonmaterial culture, folk cultures typically have strong family or clan structures and highly localized rituals. There is little division of labor other than that between the sexes. Order is maintained through sanctions based in religion or the family, and interpersonal relationships are strong. In material cultural terms, most goods are handmade, and a subsistence economy prevails. Individualism is generally weakly developed in folk cultures, as are social classes. Folk geography, a term coined by Eugene Wilhelm, is the study of the spatial patterns and ecology of these traditional groups.

31

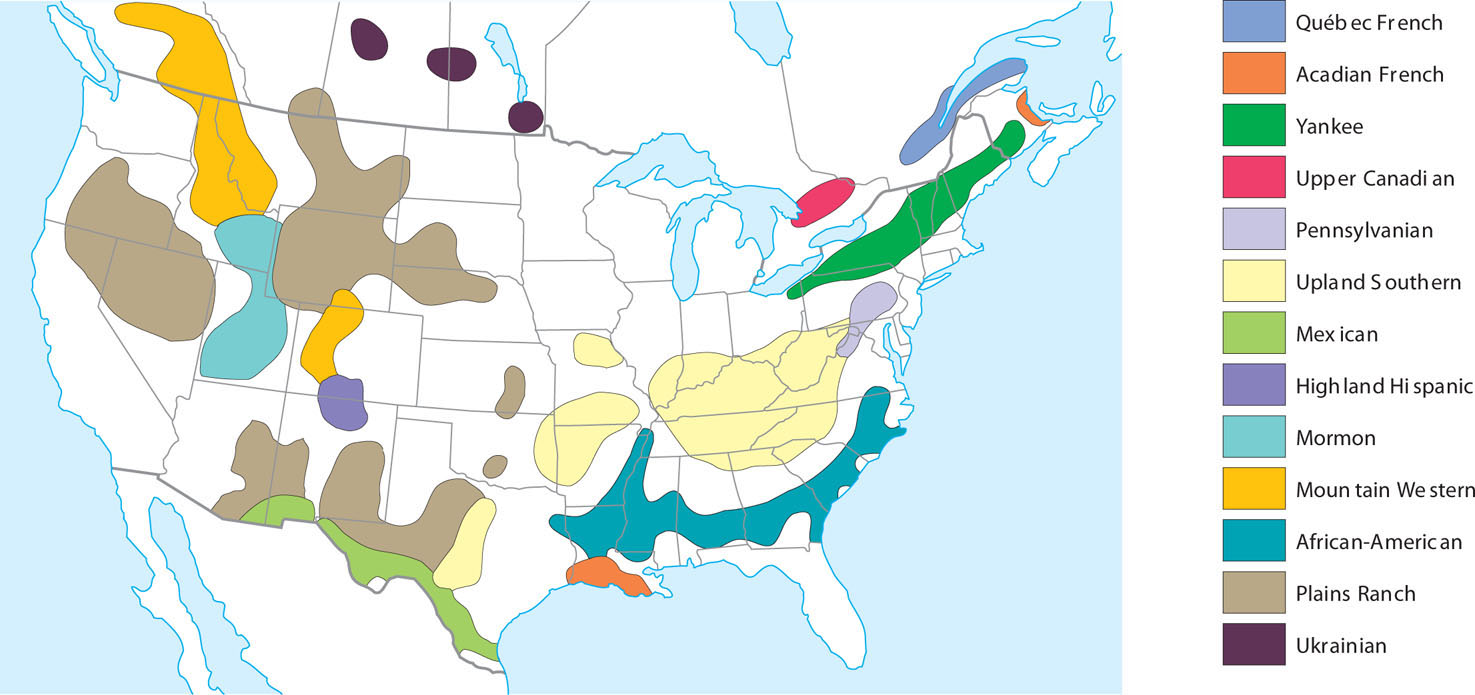

In the poorer countries of the underdeveloped world, some aspects of folk culture still exist, though few if any peoples have been left untouched by the forces of globalization. In industrialized countries, such as the United States and Canada, unaltered folk cultures no longer exist, though many remnants can be found (Figure 2.1). Perhaps the closest modern example in North America is the Amish, a German-American farming sect that largely renounces the products and labor-saving devices of the industrial age, though they do practice commercial agriculture. In Amish areas, horse-drawn buggies still serve as a local transportation device, and the faithful own no automobiles or appliances. The Amish central religious concept of demut, “humility,” clearly reflects the weakness of individualism and social class so typical of folk cultures, and a corresponding strength of Amish group identity is evident. The denomination, a variety of the Mennonite faith, provides the principal mechanism for maintaining order.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What elements of folk cultures remain in such regions? How do they become part of popular culture?

popular culture A dynamic culture based in large, heterogeneous societies permitting considerable individualism, innovation, and change; features include a money-based economy, division of labor into professions, secular institutions of control, and weak interpersonal ties; used to describe a common set of cultural ideas, values, and practices that are consumed by a population.

Popular culture is generated from and concentrated mainly in heterogeneous urban areas (Figure 2.2). Popular material goods, mass-produced by machines in factories, are consumed by the culture. A cash economy, rather than barter or subsistence, dominates. Relationships among individuals are more numerous but less personal than in folk cultures, and the family structure is weaker. Mass media such as film, print, television, radio, the Internet, and other digital media are more influential in shaping popular culture. People are more mobile, less attached to place and environment. Secular institutions of authority—such as the police, army, and courts—take the place of family and church in maintaining order. Individualism is strongly developed and innovation and change permitted or welcomed. Labor is divided into professions.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How does modern technology, itself a trait of popular culture, make widespread popular culture possible?

32

mass culture A form of culture that is produced, distributed, and marketed through mass media, art, and other forms of communication.

These characterizations of popular culture are also sometimes used to describe mass culture. However, experts point to slight differences between these two terms. Popular culture is generally used to describe a common set of cultural ideas, values, and practices that are consumed by a population. Meanwhile, mass culture usually refers more specifically to a form of culture that is produced, distributed, and marketed through mass media, art, and other forms of communication. Despite this difference in focus, for practical purposes, we can imagine that popular culture and mass culture, hand in hand, constitute the form of culture that most people in contemporary, developed societies experience daily.

If all of these characteristics seem rather commonplace and “normal,” it should not be surprising. You are, after all, firmly enmeshed in the popular culture, or you would not be attending college to seek higher education. The majority of people in the United States, Canada, and other developed nations now belong to the popular rather than the folk culture. Industrialization, urbanization, the rise of formal education, and the resultant increase in leisure time all contributed to the spread of popular culture and the consequent retreat of folklife.

In reality, all of culture presents a continuum, on which “folk” and “popular” represent two extremes. Many gradations between the two are possible.

We can use our five themes of cultural ecology—region, diffusion, ecology, interaction, and landscape—to study both folk and popular culture. Let’s begin with culture regions.