Folk and Popular Culture Diffusion

Folk and Popular Culture Diffusion

Do elements of folk culture spread through geographical space differently from those of popular culture? Whereas folk culture spreads by the same models and processes of diffusion as popular culture, diffusion operates more slowly within a folk setting. The relative conservatism of such cultures produces resistance to change. The Amish, for example, as one of the few surviving folk cultures, are distinctive today simply because they reject innovations that they believe to be inappropriate for their way of life and values.

Diffusion in Folk Culture: Agricultural Fairs

Diffusion in Folk Culture: Agricultural Fairs

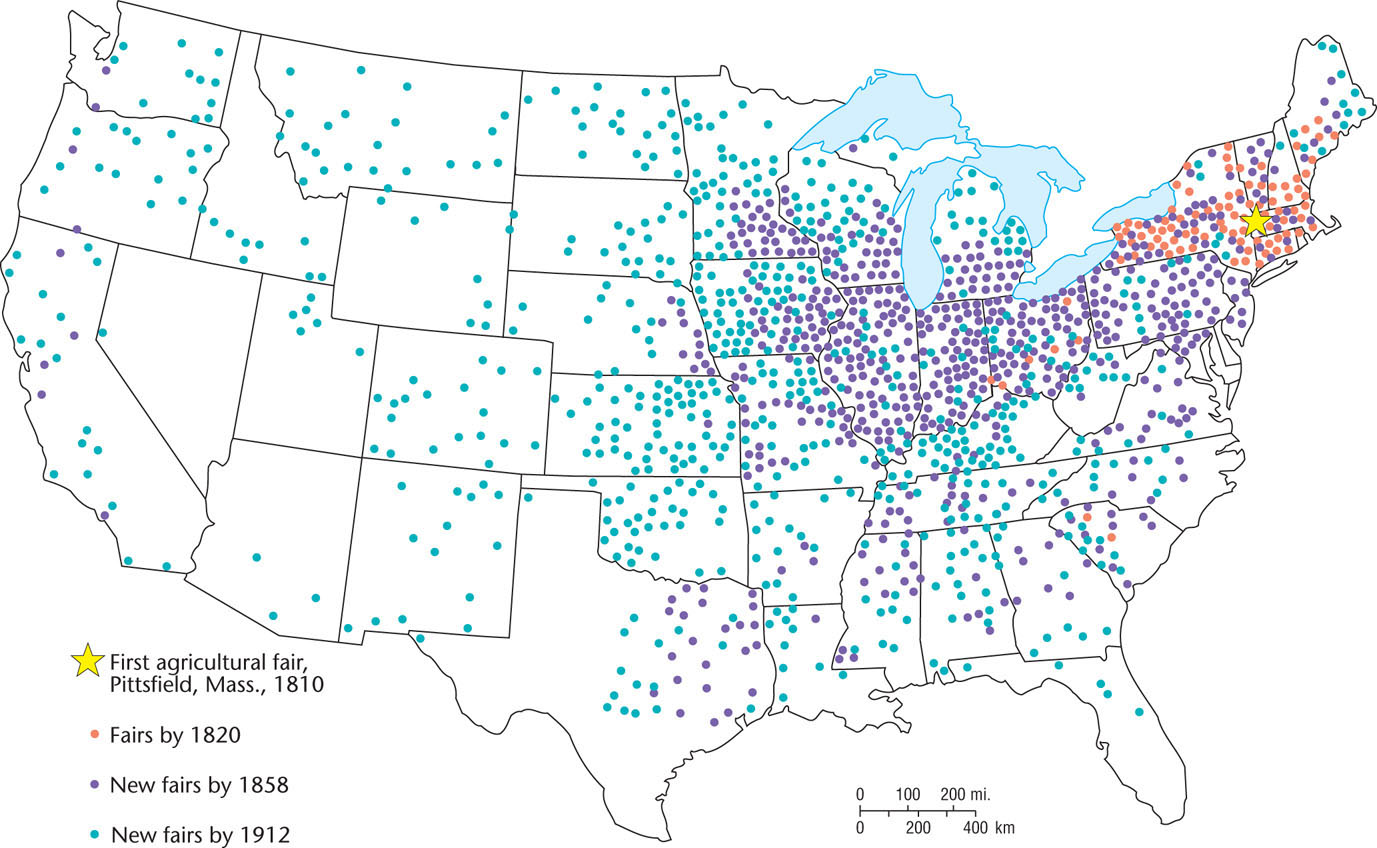

An example of folk culture that originated in the Yankee region and spread west and southwest by expansion diffusion was the American agricultural fair, a custom rooted in medieval European folk tradition. According to geographer Fred Kniffen, the first American agricultural fair was held in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in 1810, and the idea then gained favor throughout western New England and the adjacent Hudson Valley (Figure 2.15). From that source region it diffused westward into the American heartland, the Midwest, where it gained its widest acceptance.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What type or types of cultural diffusion might have been at work here?

Normally promoted by agricultural societies, the fairs were originally educational, and farmers could learn about improved methods and breeds. Soon an entertainment function was added, represented by a racetrack and midway, and competition for prizes for superior agricultural products became common. By the early twentieth century, the agricultural fair had diffused through most of the United States, although farmers in culture regions such as the Upland South did not accept it as readily or fully as did the Midwesterners.

Diffusion in Popular Culture

Diffusion in Popular Culture

Before the advent of modern transportation and mass communications, innovations usually required thousands of years to complete their areal spread, and even as recently as the early nineteenth century the time span was still measured in decades. In regard to popular culture, modern transportation and communications networks now permit cultural diffusion to occur within weeks or even days. The propensity for change makes diffusion extremely important in popular culture. The availability of devices permitting rapid diffusion enhances the chance for change in popular culture.

An example of the change from slower means of diffusion in folk culture to the rapid global spread of cultural ideas and trends in popular culture can be found in the growth of “Bollywood,” the Indian film industry. Though Bollywood is very familiar to many people around the world in twenty-first-century popular culture, its roots lie in Indian folk dance traditions and Hindi-language music that date back centuries. In the twentieth century, these traditions were transformed into popular entertainment via the development of a massive Indian film industry. Figure 2.16 illustrates the elaborate costumes and intricate dance steps that have made the Bollywood phenomenon so popular with movie audiences.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Can you think of other trends in popular culture that have diffused to the United States from folk or popular cultures in other parts of the world?

41

Due to the migration of Indian people to many other countries, and due to the recent international success of Indian films like Slumdog Millionaire, Bollywood music and dance styles have now diffused through many parts of the world. For example, in the United States, Bollywood dance has not only been featured in mainstream films, it has also become popular as a new fitness activity at many gyms and dance studios. Bollywood dance has grown in popularity on college campuses across the United States as well, with some schools sponsoring Bollywood dance teams that compete nationally against other dance teams.

In the diffusion of all types of popular culture phenomena, hierarchical processes often play a greater role than in folk culture because popular society, unlike folk culture, is highly stratified by socioeconomic class. For example, the spread of McDonald’s restaurants—beginning in 1955 in the United States and later internationally occurred hierarchically for the most part, revealing a bias in favor of large urban markets (Figure 2.17). Further facilitating the diffusion of popular culture is the fact that time-distance decay is weaker in such regions, largely because of the reach of mass media.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why might McDonald’s be considered a prestigious restaurant in countries like Russia and China?

Sometimes, however, diffusion in popular culture works differently, as a study of Walmart revealed. Geographers Thomas Graff and Dub Ashton concluded that Walmart initially diffused from its Arkansas base in a largely contagious pattern, reaching first into other parts of Arkansas and neighboring states. Simultaneously, as often happens in the spatial spread of culture, another pattern of diffusion was at work, one Graff and Ashton called reverse hierarchical diffusion. Walmart initially located its stores in smaller towns and markets, only later spreading into cities—the precise reverse of the way hierarchical diffusion normally works. This combination of contagious and reverse hierarchical diffusion led Walmart to become the nation’s largest retailer in only 30 years.

42

Advertising

Advertising

The most effective device for diffusion in popular culture, as Zelinsky suggests, confronts us almost every day of our lives. Commercial advertising of retail products and services bombards our eyes and ears with great effect. Using the techniques of social science, especially psychology, advertisers have learned how to sell us products we do not need. The skill with which advertising firms prepare commercials often determines the success or failure of a product. In short, popular culture is equipped with the most potent devices and techniques of diffusion ever devised.

Commercial advertising is limited in its capacity to overcome all spatial and cultural barriers to homogenization. Cases from international advertising are illustrative. When England-based Cadbury decided to market its line of chocolates and other candies in China, the company was forced to change its advertising strategy. Unlike much of Europe and North America, China had no culture of impulse buying and no tradition of self-service. Cadbury had to change the names of its products, avoid using mass marketing, focus on a small group of high-end consumers, and even change product content.

Place of product origin is also extremely important in trying to advertise and market internationally. Sometimes place helps sell a product—think of New Zealand wool or Italian olive oil—and sometimes it is a hindrance to sales. There are many examples of products having negative associations among consumers because the country of origin has a tarnished international reputation. A good example is South Africa’s advertising efforts during the era of apartheid when consumer boycotts of the country’s products were common. South African industries had to suppress references to country of origin in their advertising in order to market their products internationally.

Communications Barriers

Communications Barriers

Although the communications media, including the Internet, create the potential for almost instant diffusion over very large areas, this diffusion can be greatly retarded if access to the media is denied or limited. Billboard, a magazine devoted largely to popular music, described one such barrier. A record company executive complained that radio stations and disk jockeys refused to play punk rock records, thereby denying the style an equal opportunity for exposure. He claimed that punk devotees were concentrated in New York City, Los Angeles, Boston, and London, where many young people had found the style reflective of their feelings and frustrations. Without access to radio stations, punk rock could diffuse from these centers only through live concerts and the record sales they generated. The publishers of Billboard noted that “punk rock is but one of a number of musical forms which initially had problems breaking through nationally out of regional footholds.” Pachanga, ska, pop gospel, women’s music, reggae, and gangsta rap had similar difficulties. Similarly, Time Warner, a major distributor of gangsta rap music, endured scathing criticism from the U.S. Congress in 1995 because of potentially offensive or deleterious aspects of this genre. This criticism eventually led the company to sell the subsidiary label that recorded this form of rap. To control the programming of radio and television, or media distribution generally, is to control much of the diffusionary apparatus in popular culture. The diffusion of innovations ultimately depends on the flow of information.

Government censorship, as opposed to mere criticism, also creates barriers to diffusion, with varying degrees of effectiveness. In 1995, the Islamic fundamentalist regime in Iran, opposed to what it perceived as the corrupting influences of Western popular culture, outlawed television satellite dishes in an attempt to prevent citizens from watching programs broadcast in foreign countries. The Taliban government of Afghanistan went even further, banning all television sets. Control of the media can greatly control people’s tastes in, preferences in, and ideas about popular culture. Even so, repressive regimes must cope with a proliferation of communication methods, including the Internet, YouTube, and social media. So pervasive has cultural diffusion become that the insular, isolated status of nations is probably no longer attainable for very long, even under totalitarian conditions.

Reflecting on Geography

Question

Because Canadian newspapers devote so much more coverage to international stories than U.S. newspapers, are Americans more provincial than Canadians?

Diffusion of the Rodeo

Diffusion of the Rodeo

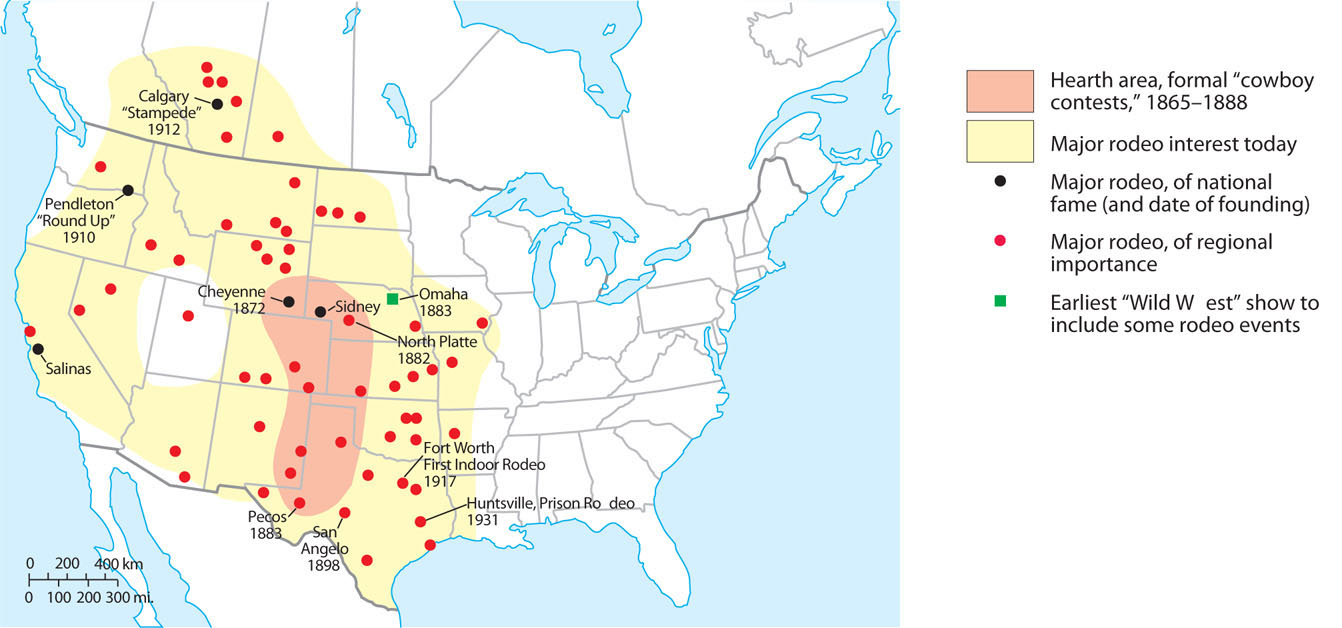

Barriers of one kind or another usually weaken the diffusion of elements of popular culture before they become ubiquitous. The rodeo provides an example. Rooted in the ranching folk culture of the American West, it has never completely escaped that setting (Figure 2.18).

Thinking Geographically

Question

What barriers might the diffusion have encountered?

Like so many elements of popular culture, the modern rodeo had its origins in folk tradition. Taking their name from the Spanish rodear, “to round up,” rodeos began simply as roundups of cattle in the Spanish livestock ranching system in northern Mexico and the American Southwest. Anglo-Americans adopted Mexican cowboy skills in the nineteenth century, and cowboys from adjacent ranches began to hold contests at roundup time. Eventually, some cowboy contests on the Great Plains became formalized, with prizes awarded.

43

The transition to commercial rodeo, with admission tickets and grandstands, came quickly as an outgrowth of the formal cowboy contests. One such affair, at North Platte, Nebraska, in 1882, led to the inclusion of some rodeo events in a Wild West show in Omaha in 1883. These shows, which moved by railroad from town to town in the manner of circuses, were probably the most potent agent of early rodeo diffusion. Within a decade of the Omaha event, commercial rodeos were being held independently of Wild West shows in several towns, such as Prescott, Arizona. Spreading rapidly, commercial rodeos had appeared throughout much of the West and parts of Canada by the early 1900s. At Cheyenne, Wyoming, the famous Frontier Days rodeo was first held in 1897. By World War I, the rodeo had also become an institution in the provinces of western Canada, where the Calgary Stampede began in 1912.

Today, rodeos are held in 36 states and three Canadian provinces. Oklahoma’s annual calendar of events lists no fewer than 98 scheduled rodeos. Rodeos have received the greatest acceptance in the popular culture found west of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers (see Figure 2.18). Absorbing and permeable barriers to the diffusion of commercial rodeo were encountered at the border of Mexico, south of which bullfighting occupies a dominant position, and in the Mormon culture region centered in Utah.

Blowguns: Diffusion or Independent Invention?

Blowguns: Diffusion or Independent Invention?

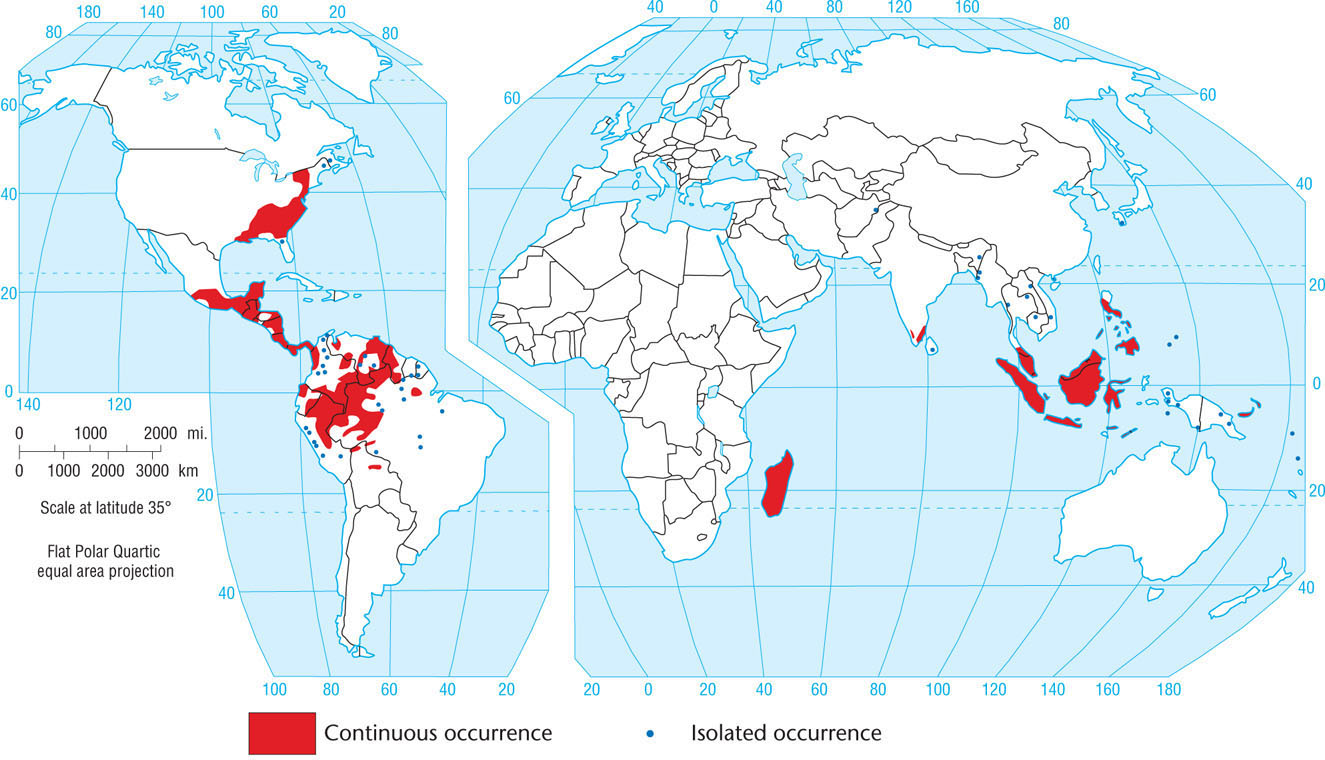

Often the path of past diffusion of an item of material culture is not clearly known or understood, presenting geographers with a problem of interpretation. The blowgun is a good example. A hunting tool of many indigenous peoples, a blowgun is a long hollow tube through which a projectile is blown by the force of one’s breath. Geographer Stephen Jett mapped the distribution of blowguns, which he discovered were used in societies in both the Eastern and Western hemispheres, all the way from the island of Madagascar off the east coast of Africa to the Amazon rain forests of South America (Figure 2.19, page 44).

Thinking Geographically

Question

Was this the result of independent invention or cultural diffusion? What kinds of data might one seek to answer this question? Compare and contrast the occurrence in the Indian and Pacific ocean lands to the distribution of the Austronesian languages (see chapter 4).

Indonesian peoples, probably on the island of Borneo, appear to have first invented the blowgun. It became their principal hunting weapon and diffused through much of the equatorial island belt of the Eastern Hemisphere. How, then, do we account for its presence among Native American groups in the Western Hemisphere? Was it independently invented by Native Americans? Was it brought to the Americas by relocation diffusion in pre-Columbian times? Or did it spread to the New World only after the European discovery of America? We do not know the answers to these questions, but the problem is common to cultural geography, especially in the study of the traditions of nonliterate cultures, which have no written records that might reveal such diffusion. Certain rules of thumb can be employed in any given situation to help resolve the issue. For example, if one or more nonfunctional features of blowguns, such as a decorative motif or specific terminology, occurred in both South America and Indonesia, then the logical conclusion would be that cultural diffusion explained the distribution of blowguns.

44