The Ecology of Folk and Popular Cultures

The Ecology of Folk and Popular Cultures

How is nature related to cultural difference? Do different cultures and subcultures differ in their interactions with the physical environment? Are some cultures closer to nature than others? People who depend on the land for their livelihood—farmers, hunters, and ranchers, for example—tend to have a different view of nature from those who work in commerce and manufacturing in the city. Indeed, one of the main distinctions between folk culture and popular culture is their differing relationships with nature.

Ethnomedicine and Ecology

Ethnomedicine and Ecology

ethnomedicine An interdisciplinary area of study that focuses on the natural ingredients and traditional practices used in folk cultures to treat illness and disease, as well as on cultural differences in perceptions of health and disease.

Folk medicine is often closely linked to the environment. People in folk societies commonly treat diseases and disorders with drugs and medicines derived from the root, bark, blossom, or fruit of plants. Medical practice using these ingredients is generally passed down orally over many generations. In recent years, these medical traditions have received increased interest in many disciplines, including anthropology, botany, and geography. In addition to studying the natural ingredients that folk cultures use to treat illness and disease, ethnomedicine examines the cultural interpretation of health and disease. Most folk cultures interpret these conditions as the result of two basic causes: (1) natural forces, like heat or cold, and (2) unnatural forces, like evil spirits.

As a result of increasing interest in ethnomedicine and the proven effectiveness of many of its cures and practices, mainstream medical practitioners in many countries (including the United States) have begun to incorporate folk medicines and practices from around the world into the treatment of their patients. For example, traditional Chinese medicine has become quite widely accepted, leading to the popularity of treatments like acupuncture and therapeutic massage. In addition, many modern drugs have been developed from traditional folk ingredients. For example, aspirin was developed from folk uses of the willow tree, and certain cancer drugs have evolved from folk traditions using the periwinkle flower. American folk medicine traditions have also influenced mainstream medical practice. These traditions have been best preserved in the Upland South, on some Indian reservations, and in the Mexican borderland.

45

The outlook of the Upland Southerner toward cures is well expressed in the comments of an eastern Tennessee mountaineer root digger who, in an interview with cultural geographer Edward Price, said that “the good Lord has put these yerbs here for man to make hisself well with. They is a yerb, could we but find it, to cure every illness.” Root digging has been popularized to the extent that much of the produce of the Appalachians is now funneled to dealers, who serve a larger market outside the folk culture. Nonetheless, root digging remains at heart a folk enterprise, carried on in the old ways and requiring the traditionally thorough knowledge of the plant environment.

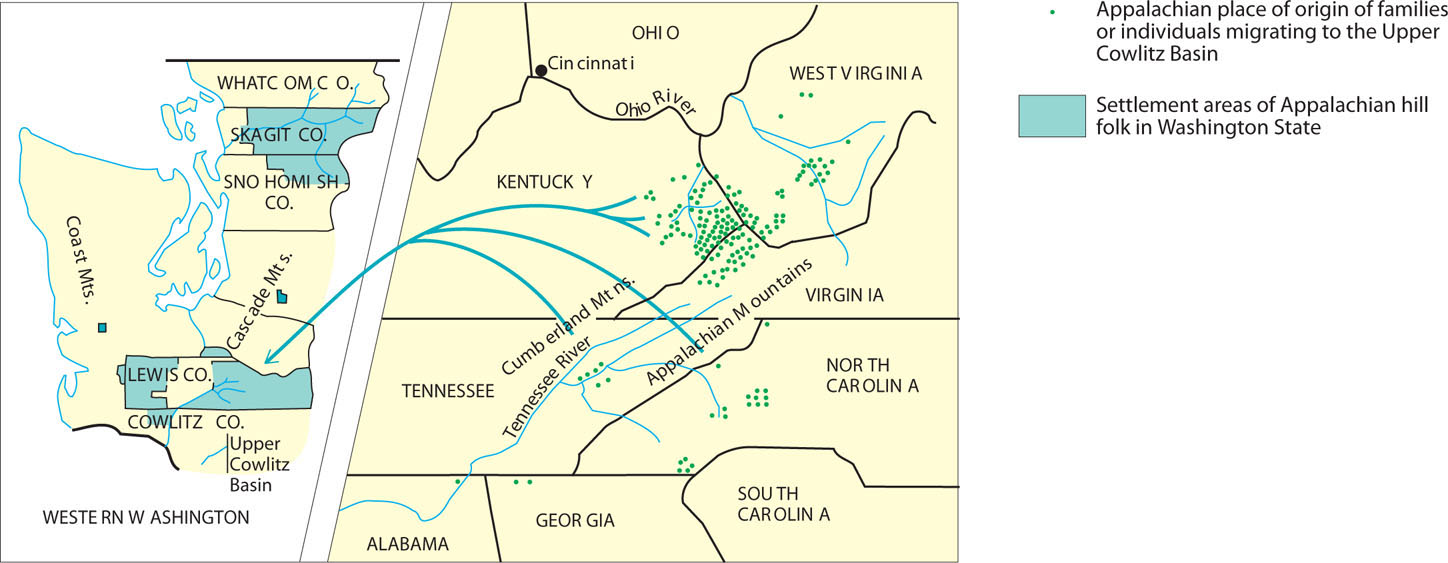

Although the attention to conservation varies from culture to culture, folk cultures’ close ties to the land and local environment enhance the environmental perception of folk groups. This becomes particularly evident when they migrate. Typically, they seek new lands similar to the ones left behind. A good example can be seen in the migrations of Upland Southerners from the mountains of Appalachia between 1830 and 1930. As the Appalachians became increasingly populous, many Upland Southerners began looking elsewhere for similar areas to settle. Initially, they found an environmental twin of the Appalachians in the Ozark-Ouachita Mountains of Missouri and Arkansas. Somewhat later, others sought out the hollows, coves, and gaps of the central Texas Hill Country. The final migration of Appalachian hill people brought some 15,000 members of this folk culture to the Cascade and Coast mountain ranges of Washington State between 1880 and 1930 (Figure 2.20).

Thinking Geographically

Question

What does the high degree of clustering of the sources of the migrants and subsequent clustering in Washington suggest about the processes of folk migrations? How should we interpret their choices of familiar terrain and vegetation for a new home? Why might members of a folk society who migrate choose a new land similar to the old one?

People so close to nature tend to remain sensitive to very subtle environmental qualities. Nowhere is this sensitivity more evident than in the practice of “planting by the signs,” found among folk farmers in the United States and elsewhere. Reliance on the movement and appearance of planets, stars, and the moon might seem absurd to the managers of huge corporate farms, but these beliefs and practices still exist among the members of folk cultures.

Nature in Popular Culture

Nature in Popular Culture

Popular culture is less directly tied to the physical environment than folk culture, which is not to say that popular culture does not have an enormous impact on the environment. Urban dwellers generally do not draw their livelihoods from the land. They have no direct experience with farming, mining, or logging activities, though they could not live without the commodities produced from those activities. Gone is the intimate association between people and land known by our folk ancestors. Gone, too, is our direct vulnerability to many environmental forces, although the security is more apparent than real. Because popular culture is so tied to mass consumption, it can have enormous environmental impacts, such as the production of air and water pollution and massive amounts of solid waste. Also, because popular culture fosters limited contact with and knowledge of the physical world, usually through recreational activities, our environmental perceptions can become quite distorted.

46

Popular culture makes heavy demands on ecosystems. This is true even in the seemingly benign realm of recreation. Recreational activities have increased greatly in the world’s economically affluent regions. Many of these activities require machines, such as snowmobiles, off-road vehicles, and jet skis, that are powered by internal combustion engines and have numerous adverse ecological impacts ranging from air pollution to soil erosion. In national parks and protected areas worldwide, affluent tourists in search of nature have overtaxed protected environments and wildlife and produced levels of congestion approaching those of urban areas (Figure 2.21).

Thinking Geographically

Question

What kind of diffusion would be involved in the spread of the desire to visit Yosemite (and other popular national parks)? What environmental impacts would result?

Such a massive presence of people in our recreational areas inevitably results in damage to the physical environment. A study by geographer Jeanne Kay and her students in Utah revealed substantial environmental damage done by off-road recreational vehicles, including “soil loss and long-term soil deterioration.” One of the paradoxes of the modern age and popular culture seems to be that the more we cluster in cities and suburbs, the greater our impact on open areas; we carry our popular culture with us when we vacation in such regions.