Diffusion in Population Geography

Diffusion in Population Geography

How does demography relate to the theme of diffusion? After natural increases and decreases in populations, the second basic way that population numbers are altered is the result of the migration of people from one place to another, and it offers a straightforward illustration of relocation diffusion. When people migrate, they sometimes bring more than simply their culture; they can also bring disease. The introduction of diseases to new places can have dramatic and devastating consequences. Thus, the spread of diseases is also considered as part of the theme of diffusion because disease has a direct bearing on population geography.

Migration

Migration

Humankind is not tied to one locale. Homo sapiens most likely evolved in Africa, and ever since, we have proved remarkably able to adapt to new and different physical environments. We have made ourselves at home in all but the most inhospitable climates, shunning only such places as ice-sheathed Antarctica and the shifting sands of the Arabian Peninsula’s Empty Quarter. Our permanent habitat extends from the edge of the ice sheets to the seashores, from desert valleys below sea level to high mountain slopes. This far-flung distribution is the product of migration.

Early human groups moved in response to the migration of the animals they hunted for food and the ripening seasons of the plants they gathered. Indeed, the agricultural revolution, whereby humans domesticated crops and animals and accumulated surplus food supplies, allowed human settlements to stop their seasonal migrations. Why, then, did certain groups opt for long-distance relocation? Some migrated in response to environmental collapse, others in response to religious or ethnic persecution. Still others—probably the majority, in fact—migrated in search of better opportunities. For those who migrate, the process generally ranks as one of the most significant events of their lives. Even ancient migrations often remain embedded in folklore for centuries or millennia.

The Decision to Move

voluntary migrant A person leaving his or her place of residence in order to improve his or her quality of life, often for the purpose of employment.

forced migrant A migrant whose movements are coerced by threats to life and livelihood or by threats arising from natural or human-made causes

refugee A person fleeing from persecution in his or her country of nationality. The persecution can be religious, political, racial, or ethnic. A refugee is a forced migrant..

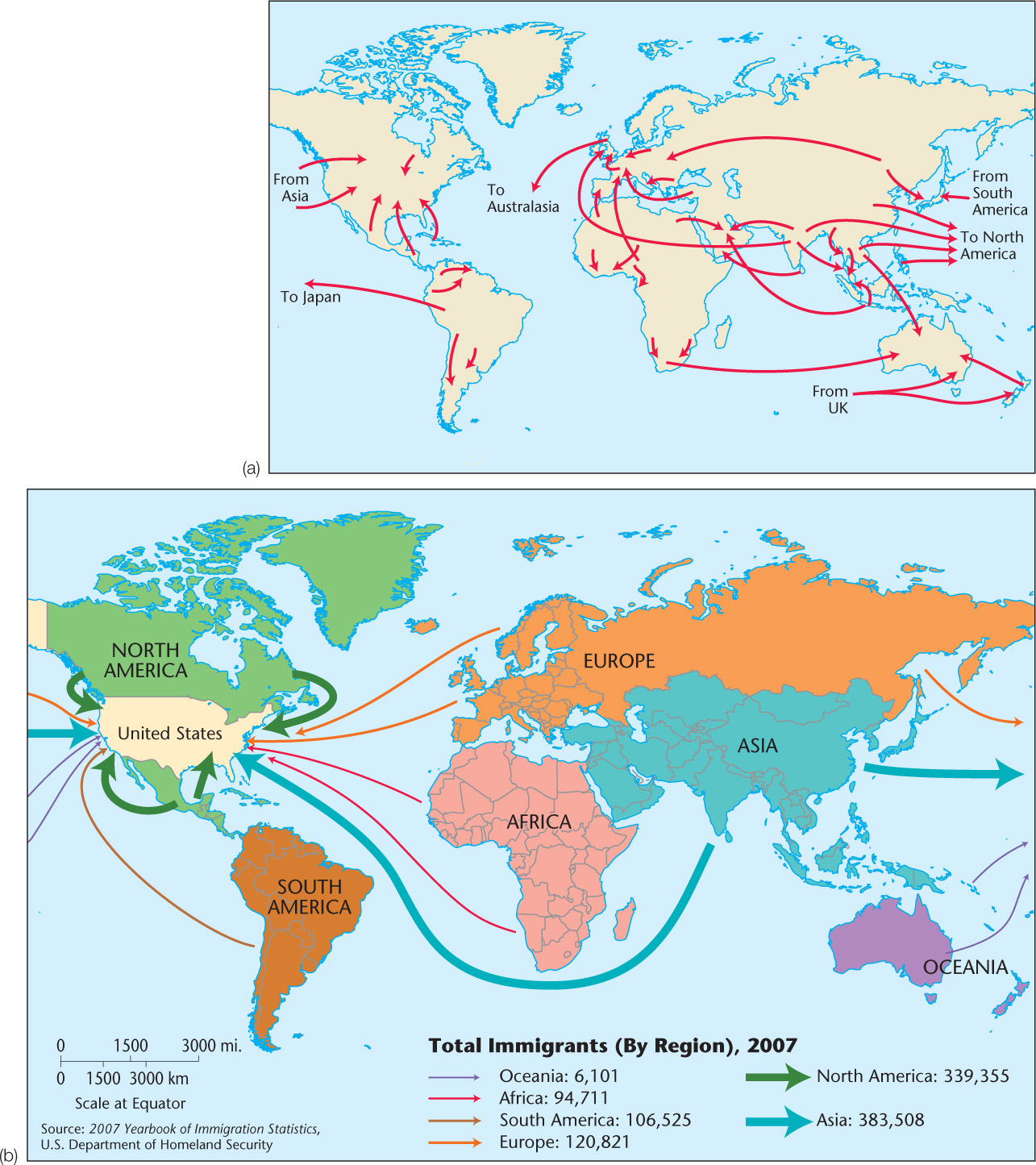

The Decision to Move Migration takes place when people decide that moving is preferable to staying and when the difficulties of moving seem to be more than offset by the expected rewards. In the nineteenth century, more than 50 million European emigrants left their homelands in search of better lives. Today, migration patterns are very different (Figure 3.15). Europe, for example, now predominantly receives immigrants rather than sending out emigrants. International migration stands at an all-time high, with about 240 million people (3.1 percent of the world’s population) living outside of the country of their birth. Much of this movement is due to labor migration associated with globalization. However, not all migrants are voluntary migrants. In fact, millions of individuals around the world today are forced migrants who have either been internally displaced within their own countries (27.5 million) or are refugees (15.4 million) fleeing political, ethnic or religious persecution, wars, famines, or other natural and environmental disasters. Interestingly, economic persecution does not fall under the definition of refugee. Forced migrations have occurred many times throughout history. The westward displacement of the Native American population of the United States; the dispersal of Jews from Palestine in Roman times and from Europe in the mid-twentieth century; the export of Africans to the Americas as slaves; and the Clearances, or forced removal of farmers from Scotland’s Highlands to make way for large-scale sheep raising, provide depressing examples.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why do you think that there are major migration flows from parts of Africa and Asia to Europe? What reasons can you give for the comparatively high number of migrants coming from Canada and Mexico to the United States?

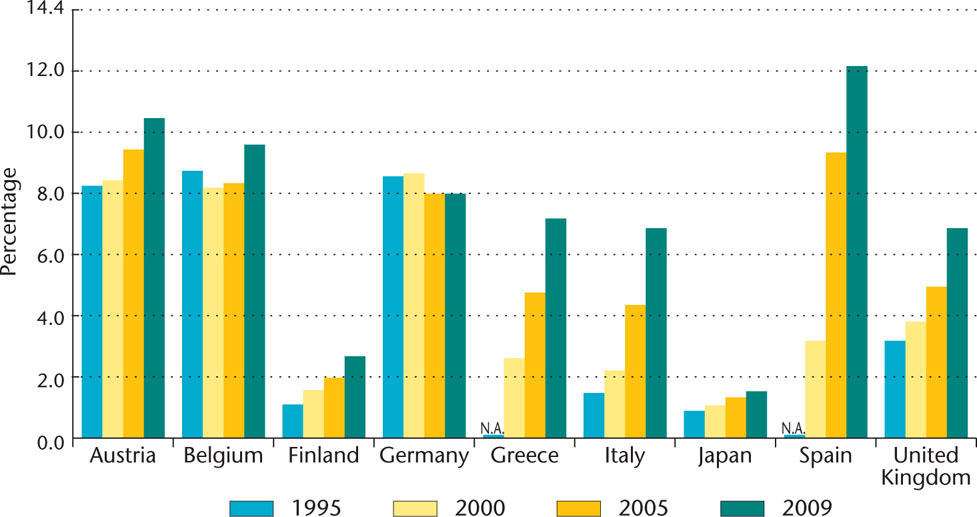

75

Though the total rate of migration around the world has remained fairly stable in the past decade, rates of migration from country to country vary greatly. For example, the population of the state of Qatar in western Asia is composed of approximately 76 percent migrants, while the population of Indonesia has only 0.07 percent migrants. Figure 3.16 provides further data regarding the percentage of selected national populations that is composed of foreign-born individuals. The U.S. population is approximately 13 percent foreign-born. Within countries, the rate of domestic, or internal, migration varies greatly as well. In traditional societies, people have often chosen to remain close to the location of their birth throughout their lives. However, this trend has been changing in recent decades due to increasing urbanization in many developing states, because most opportunities for education and employment tend to be found in cities. These internal migrations to burgeoning twenty-first-century cities may be rewarded with higher wages or greater access to education, but they also entail many risks, particularly for certain ethnic minorities. Language barriers, lack of access to adequate health care and other social services, discrimination, and abuse of many kinds often await workers desperate to better their economic situation. Indeed, the United States has a long history of internal movement for the purpose of securing better economic opportunity and other personal reasons. In fact, more than 10 million Americans moved to other counties within the United States during 2008 alone.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What factors do you think may influence migrants’ decisions to move to one country versus another country?

76

push-and-pull factors Unfavorable, repelling conditions and favorable, attractive conditions that interact to affect migration and other elements of diffusion.

Every migration, from the ancient dispersal of humankind out of Africa to the present-day movement toward urban areas, is governed by a host of push-and-pull factors that act to make the old home unattractive or unlivable and the new land attractive. Generally, push factors are the most important. After all, a basic dissatisfaction with the homeland is prerequisite to voluntary migration. The most important factor prompting migration throughout the thousands of years of human existence is economic. More often than not, migrating people seek greater prosperity through better access to resources, especially land. Both forced migrations and refugee movements, however, challenge the basic assumption of the push-and-pull model, which posits that human movement is the result of unforced choices.

Disease Diffusion and Medical Geography

Disease Diffusion and Medical Geography

medical geography The branch of geography that deals with health and disease-related topics.

The branch of geography that deals most closely with health and disease-related topics is medical geography. Medical geographers seek to understand the various factors that affect the health of populations and to discover and map spatial patterns of disease and health-care provision. The foundations of medical geography and an interest in relationships between place and disease can be traced back as far as the time of Hippocrates in the third century B.C. Hippocrates observed, even at that time, that certain diseases seemed to occur in some places but not in others. In other words, Hippocrates recognized that diseases both move in spatially specific ways and occasion responses that are spatial in nature.

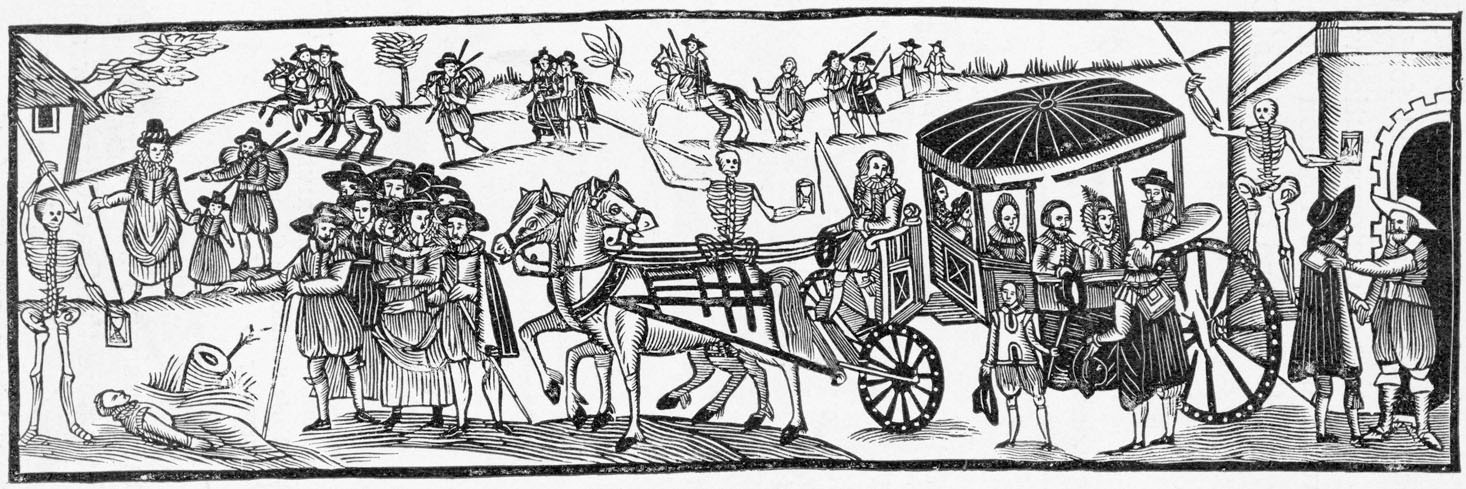

Throughout history, infectious disease has periodically decimated human populations. One has only to think of the vivid accounts of the Black Death episodes that together killed one-third of medieval Europe’s population to get a sense of how devastating disease can be (Figure 3.17).

Thinking Geographically

Question

How do modern outbreaks of disease influence travel?

The spread of disease provides classic illustrations of both expansion and relocation diffusion. Some diseases are noted for their tendency to expand outward from their point of origin. Commonly borne by air or water, the viral pathogens for contagious diseases such as influenza and cholera spread from person to person throughout an affected area. Some diseases spread in a hierarchical diffusion fashion, whereby only certain social strata are exposed. The poor, for example, have always been much more exposed to the unsanitary conditions—rats, fleas, excrement, and crowding—that have occasioned disease epidemics. Other illnesses, particularly airborne diseases, affect all social and economic classes without regard for human hierarchies: their diffusion pattern is literally contagious.

77

Indeed, disease and migration have long enjoyed a close relationship. Diseases have spread and relocated thanks to human movement. Likewise, widespread human migrations have occurred as the result of disease outbreaks.

When humans engage in long-distance mobility, their diseases move along with them. Thus, cholera—a waterborne disease that had for centuries been endemic to the Ganges River region of India—broke out in Calcutta in the early 1800s. Because Calcutta was an important node in Britain’s colonial empire, cholera quickly began to spread far beyond India’s borders. Soldiers, pilgrims, traders, and travelers spread cholera throughout Europe, then from port to port across the world through relocation diffusion, making cholera the first disease of global proportions.

Early responses to contagious diseases were often spatial. Isolation of infected people from the healthy population—known as quarantine—was practiced. Sometimes only the sick individuals were quarantined, whereas at other times households or entire villages were shut off from outside contact. Whole shiploads of eastern European immigrants to New York City were routinely quarantined in the late nineteenth century. Another early spatial response was to flee the area of infection. During the time of the plague in fourteenth-century Europe, some healthy individuals abandoned their ill neighbors, spouses, and even children. Some of them formed altogether separate communities, whereas others sought merely to escape the city walls for the countryside.

Targeted spatial strategies could be enacted once it became known that some diseases spread through specific means. The best-known example is John Snow’s 1854 mapping of cholera outbreaks in London, illustrated in Figure 3.18, which allowed him to trace the source of the infection to one water pump. Thanks to his detective work and the development of a broader medical understanding of the role of germs in the spread of disease, cholera was understood as a waterborne disease that could be controlled by increasing the sanitary conditions of water delivery.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What evidence could a geographer use to track the source of an airborne disease?

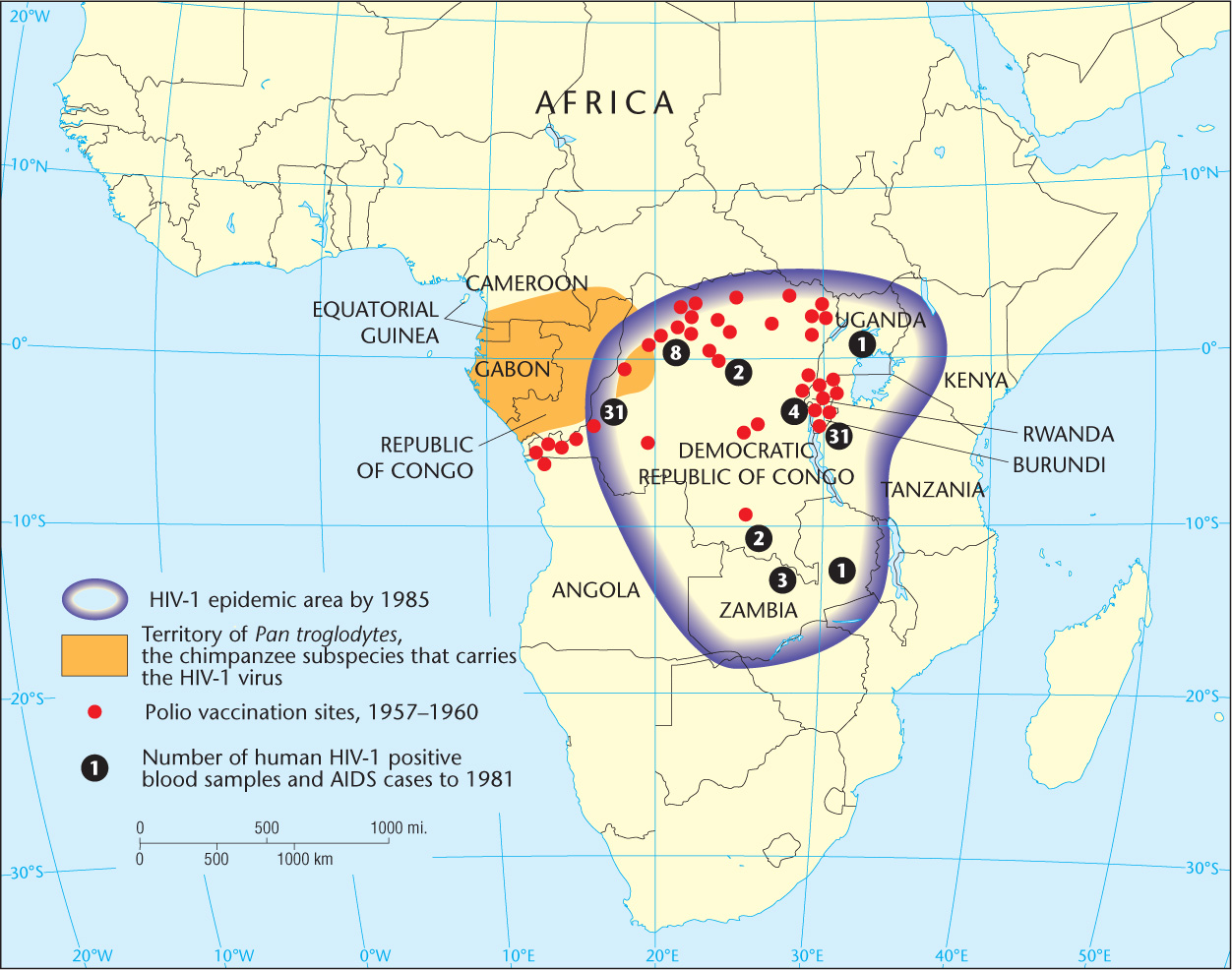

The threat of deadly disease is hardly a thing of the past. Today, medical geographers conduct important research used in the making of health-care policy, in the planning of health-care systems, and in the treatment of disease. This research can particularly benefit rural populations and those in developing regions that have relatively high rates of infant mortality, malnutrition, HIV/AIDS, and other indicators of poor health care. It is hoped that mapping the spread of these contemporary diseases, understanding the pathways traveled by their carriers, and developing appropriate spatial responses can help prevent mass epidemics and disease-related panics (Figure 3.19).

Thinking Geographically

Question

How is the effect of long-distance truck transportation evident in the locations of the first HIV-1 positive blood samples in 1981?

Though the work of medical geographers is critical to improving quality of life for the world’s citizens, unfortunately it is often impeded by an inability to collect accurate data in many regions. For example, due to linguistic and other cultural differences, geographers can seldom be sure that medical terminology, diagnostic techniques, and medical data collection techniques are standardized across regions and countries. In addition, the ability for an ill person to see a doctor varies greatly from region to region and country to country. This makes the incidence of disease and other health problems difficult to accurately measure and map. Despite these obstacles, medical geographers strive to produce maps and other forms of data that enable health-care professionals and governments assess and provide health-care needs.

78