Cultural Interaction and Population Patterns

Cultural Interaction and Population Patterns

Can we gain additional understanding of demographic patterns by using the theme of cultural interaction? Are culture and demography intertwined? Yes, in diverse and causal ways. Culture influences population density, migration, and population growth. Inheritance laws, food preferences, politics, differing attitudes toward migration, and many other cultural features can influence demography.

Cultural Factors

Cultural Factors

Many of the forces that influence the distribution of people are basic characteristics of a group’s culture. For example, we must understand the preference for rice of people living in Southeast Asia before we can try to interpret the dense concentrations of people in rural areas there. The population in the humid lands of tropical and subtropical Asia expanded as this highly prolific grain was domesticated and widely adopted. Environmentally similar rural zones elsewhere in the world, where rice is not a staple of the inhabitants’ diet, never developed such great population densities. Similarly, the introduction of the potato into Ireland in the 1700s allowed a great increase in rural population, because it yielded much more food per acre than did traditional Irish crops. Failure of the potato harvests in the 1840s greatly reduced the Irish population, through both starvation and emigration.

Geographers have found major cultural contrasts in attitudes toward population growth. Sustained fertility decline first took place in France in the nineteenth century, but neighboring countries such as Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom did not experience the same decline. France, the most populous of these four countries in the 1800s, became the least populous shortly after 1930. During this same period, millions of Germans, British people, and Italians emigrated overseas, whereas relatively few French left their homeland. Clearly, some factor in the culture of France worked to produce the demographic decline. What might the reason be?

Cultural groups also differ in their tendency to migrate. Religious ties bind some groups to their traditional homelands, while other religious cultures place no stigma on migration. In fact, some groups, such as the Irish until recently, consider migration a way of life.

personal space The amount of space that individuals feel “belongs” to them as they go about their daily business.

Culture can also condition a people to accept or reject crowding. Personal space—the amount of space that individuals feel “belongs” to them as they go about their everyday business—varies from one cultural group to another. When Americans talk to one another, they typically stand farther apart than, say, Italians do. The large personal space demanded by Americans may well come from a heritage of sparse settlement. Early pioneers felt uncomfortable when they first saw smoke from the chimneys of neighboring cabins. As a result, American cities sprawl across large areas, with huge suburbs dominated by separate houses surrounded by private yards. Most European cities are compact, and their residential areas consist largely of row houses or apartments.

82

Political and Economic Factors

Political and Economic Factors

The political mosaic is linked to population geography in many ways. Governmental policies, such as China’s one-child policy, often influence the fertility rate, and forced migration is usually the result of political forces.

Governments can also restrict voluntary migration. Two independent countries, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, share the tropical Caribbean island of Hispaniola. Haiti is far more densely settled than the Dominican Republic. Government restrictions make migration from Haiti to the Dominican Republic difficult and help maintain the different population densities. If Hispaniola were one country, its population would be more evenly distributed over the island.

Governments also set in motion most involuntary migrations. These have become common in the past century or so, usually to achieve ethnic cleansing—the removal of unwanted minorities from nation-states. A twenty-first-century example of ethnic cleansing occurred in the Darfur region of Sudan, where decades of conflict between various rebel groups and the Muslim Sudanese government resulted in the deaths of over 1.5 million people and the displacement of over 2.5 million people from their homes. After more than eight years of armed disputes and widespread raids on villages in the region, a 2005 referendum decided that the southern region of the country (populated by a number of distinct ethnic groups) would split from the Arab north to form the new nation-state of South Sudan. This split officially occurred on July 9, 2011. The infant nation-state of South Sudan faces many challenges, as it is oil-rich but is also one of the more poorly developed nations on Earth. Most children in South Sudan below age 13 are not in school, and more than 80 percent of the nation’s females are illiterate. Further, there are issues to be resolved between Sudan and its new southern neighbor involving citizenship rights, oil pipeline ownership rights, and many other political issues.

In addition to involuntary migrations of populations precipitated by governments, economic conditions often influence population density in profound ways. The industrialization of the past 200 years has caused the greatest voluntary relocation of people in world history. Within industrial nations, people have moved from rural areas to cluster in manufacturing regions. Agricultural changes can also influence population density. For example, the complete mechanization of cotton and wheat cultivation in twentieth-century America allowed those crops to be raised by a much smaller labor force. As a result, profound depopulation occurred, to the extent that many small towns serving these rural inhabitants ceased to exist.

Population Control Programs

Population Control Programs Though the debates may occur at a global scale, most population control programs are devised and implemented at the national level. When faced with perceived national security threats, some governments respond by supporting pronatalist programs that are designed to increase the population. Labor shortages in Nordic countries have led to incentives for couples to have larger families. Most population programs, however, are antinatalist: they seek to reduce fertility. Needless to say, this is an easier task for a nonelected government to carry out because limiting fertility challenges traditional gender roles and norms about family size.

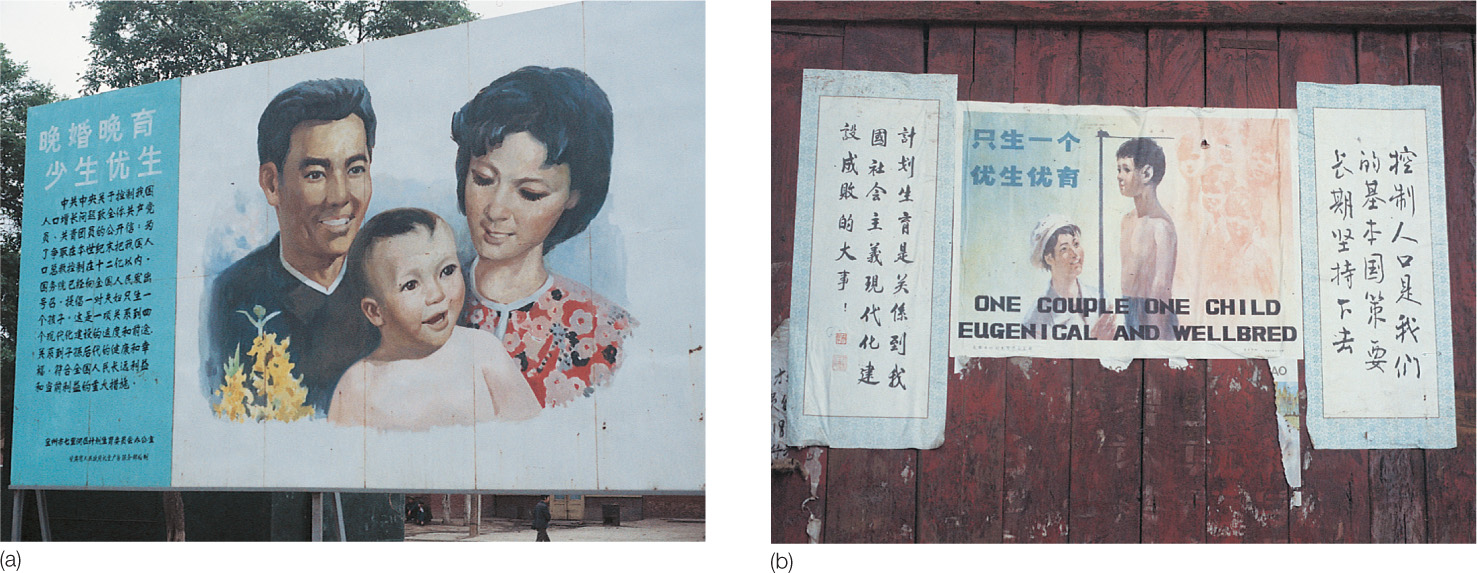

Although China is not the only country that has sought to limit its population growth, its so-called “one-child policy” provides the best-known modern example. Mao Zedong, the leader of the People’s Republic of China from 1949 to 1976, did not initially discourage large families because he believed that “every mouth comes with two hands.” In other words, he believed that a large population would strengthen the country in the face of external political pressures. He reversed his position in the 1970s, when it became clear that China faced resource shortages as a result of its burgeoning population. In 1979, the one-child-per-couple policy was adopted. With it, Chinese authorities sought not merely to halt population growth but ultimately to decrease the national population. Some families were exempt from this policy, including ethnic minority households and farming families whose first child was female. These exceptions were granted to prevent ethnic minority populations from dying out over time and to allow farming families to produce a male child to help with agricultural work and eventually to take over the family farm. Outside of these exceptions, during the three decades that the one-child policy has been in force, billboards and posters admonishing citizens that “one couple, one child” is the ideal family have been commonplace on the Chinese cultural landscape (Figure 3.21). Violators of the policy have faced huge monetary fines and ineligibility for new housing. They have also lost government benefits to the elderly, access to higher education for their children, and even their jobs. In addition to enforcing these penalties, the Chinese government has sought to slow population growth by encouraging late marriages (thus delaying the start of families). In response, between 1970 and 1980, the TFR in China plummeted from 5.9 births per woman to only 2.7, then to 2.2 by 1990, 2.0 by 1994, 1.7 in 2007, and 1.5 in 2011.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How effective would such billboards be in influencing people’s decisions? Why is one of the signs in English?

83

As a result of these policies, China achieved one of the greatest short-term reductions of birthrates ever recorded, thus proving that cultural changes can be imposed from above, rather than simply by waiting for them to diffuse organically. In recent years, the Chinese population control program has been less rigidly enforced, as periods of economic growth eroded the government’s control over the people. This relaxation allowed more couples to have two children instead of one; however, the rise of economic opportunity and migration to cities have led some couples to have smaller families voluntarily. Recently, the Chinese government has acknowledged that the country’s socioeconomic trends, along with its rigid 30-year policy, have created significant demographic imbalances. For example, the gender ratio went from 108.5 boys to 100 girls in the early 1980s to 111 boys in 1990 to 116 in 2000, and it is now at nearly 120 boys for every 100 girls. This imbalance is largely due to millions of families over the past 30 years resorting to abortion (aided by widespread but illegal prenatal ultrasound scans) and female infanticide in order to ensure that their one child was a boy. (Throughout Chinese history, male children have represented continuity of the family lineage and protection and support for the parents in their old age. These ideas are still very much alive in China.)

As a result of worry over the implications of growing gender imbalances, the Chinese government has begun to consider whether to move to a two-child policy within the next five years. However, some opponents of the changes have argued that the result will be a sudden surge in the number of births, creating new social problems. Nevertheless, proposals are being discussed that may allow families whose first child is a girl to have a second child as early as 2015. Relaxing policies in this way could help ease the future burden of the Chinese working population to support an ever-growing elderly population, which will account for one-third of the country’s people in the next three decades. It is also hoped that loosening the one-child policy will decrease the rising incidence of human trafficking in China as more and more men resort to “purchasing” their wives from “bachelors’ villages” that have begun to spring up in remote areas of the country.

Reflecting on Geography

Question

Would a global population control policy be desirable—or even feasible?