Linguistic Diffusion

Linguistic Diffusion

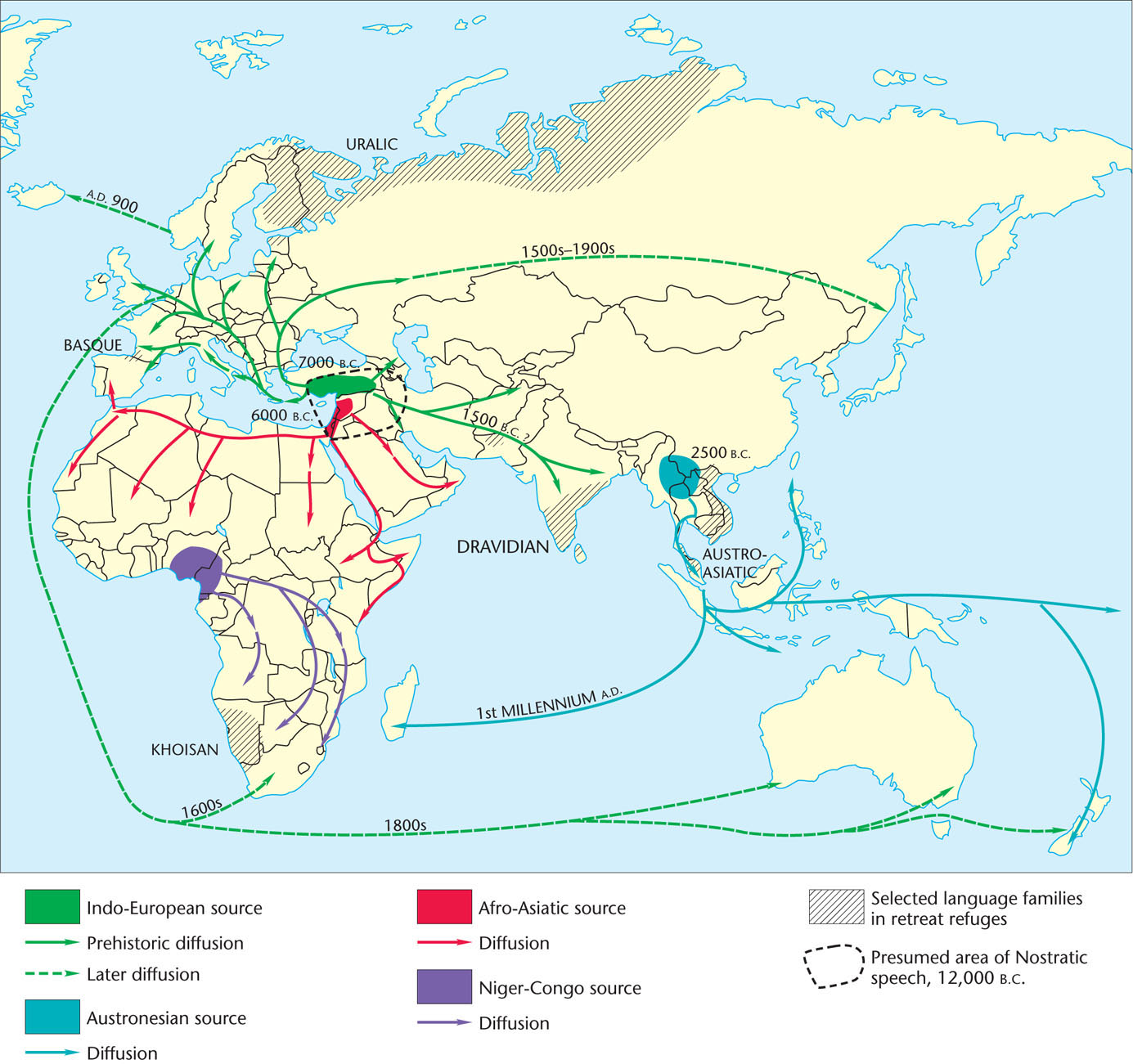

How did the mosaic of languages and dialects come to exist? How is the spatial patterning of language changing today? Different types of cultural diffusion have helped shape the linguistic map. Relocation diffusion has been extremely important because languages spread when groups, in whole or in part, migrate from one area to another. Some individual tongues or entire language families are no longer spoken in the regions where they originated, and in certain other cases the linguistic hearth is peripheral to the present distribution (compare Figure 4.1 and Figure 4.7). Today, languages continue to evolve and change based on the shifting locations of peoples and on their needs, as well as on outside forces.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why would language diffuse along with agriculture?

Indo-European Diffusion

Indo-European Diffusion

Anatolian hypothesis A theory of language diffusion holding that the movement of Indo-European languages from the area in contemporary Turkey known as Anatolia followed the spread of plant domestication technologies.

According to a widely accepted new theory, the earliest speakers of the Indo-European languages lived in southern and southeastern Turkey, a region known as Anatolia, about 9000 years ago. According to the so-called Anatolian hypothesis, the initial diffusion of these Indo-European speakers was facilitated by the innovation of plant domestication. As sedentary farming was adopted throughout Europe, a gradual and peaceful expansion and diffusion of Indo-European languages occurred. As these people dispersed and lost contact with one another, different Indo-European groups gradually developed variant forms of the language, causing fragmentation of the language family.

Kurgan hypothesis A theory of language diffusion holding that the spread of Indo-European languages originated with animal domestication; originated in the Central Asian steppes; and was later, more violent, and swifter than proponents of the Anatolian hypothesis maintain.

The Anatolian hypothesis has been criticized by scholars who note that specific terms related to animals, particularly horses, as opposed to agriculture, link Indo-European languages to a common origin. The so-called Kurgan hypothesis places the rise of Indo-European languages in the central Asian steppes only 6000 years ago, positing that the spread of Indo-European languages was both swifter and less peaceful than believed by those who subscribe to the Anatolian hypothesis. No one theory has been definitively proven to be correct.

What is more certain is that in later millennia, the diffusion of certain Indo-European languages—in particular Latin, English, and Russian—occurred in conjunction with the territori al spread of great political empires. In such cases of imperial conquest, relocation diffusion and expansion diffusion were not mutually exclusive. Relocation diffusion occurred as a small number of conquering elite came to rule an area. The language of the conqueror, implanted by relocation diffusion, often gained wider acceptance through expansion diffusion. Typically, the conqueror’s language spread hierarchically—adopted first by the more important and influential persons and by city dwellers. The diffusion of Latin with Roman conquests, and Spanish with the conquest of Latin America, occurred in this manner.

Austronesian Diffusion

Austronesian Diffusion

One of the most impressive examples of linguistic diffusion is that of the Austronesian languages, 5000 years ago, from a presumed hearth in the interior of Southeast Asia that was completely outside the present Austronesian culture region. From here, it is theorized, speakers of this language family first spread southward into the Malay Peninsula (see Figure 4.7). Then, in a process lasting perhaps several thousand years and requiring remarkable navigational skills, they migrated through the islands of Indonesia and sailed in tiny boats across vast, uncharted expanses of ocean to New Zealand, Easter Island, Hawaii, and Madagascar. If agriculture was the technology permitting Indo-European diffusion, sailing and navigation provided the key to the spread of the Austronesians.

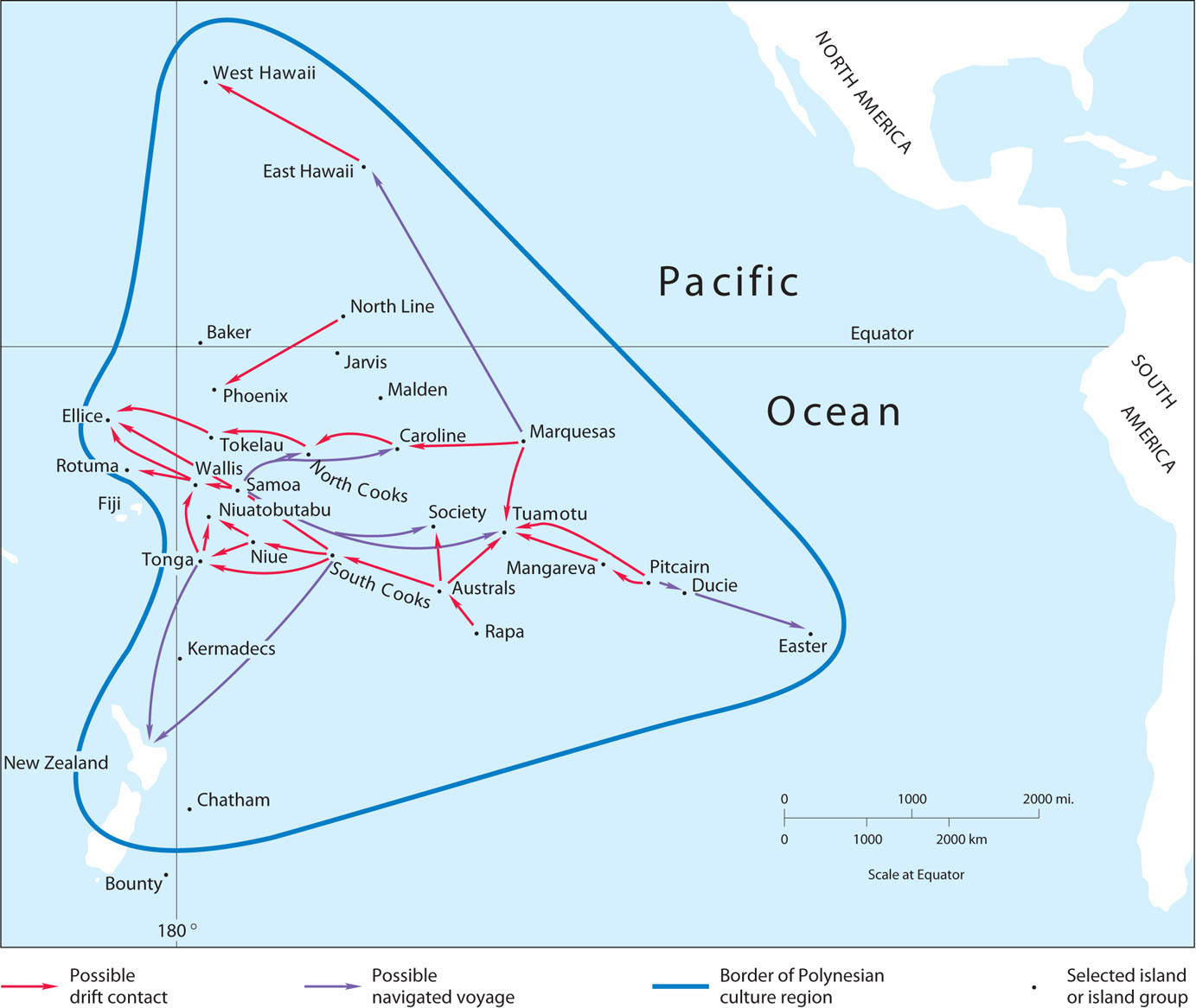

Most remarkable of all was the diffusionary achievement of the Polynesian people, who form the eastern part of the Austronesian culture region. Polynesians occupy a triangular realm consisting of hundreds of Pacific islands, with New Zealand, Easter Island, and Hawaii at the three corners (Figure 4.8, below). The Polynesians’ watery leap of 2500 miles (4000 kilometers) from the South Pacific to Hawaii, a migration in outrigger canoes against prevailing winds into a new hemisphere with different navigational stars, must rank as one of the greatest achievements in seafaring. No humans had previously found the isolated Hawaiian Islands, and the Polynesian sailors had no way of knowing ahead of time that land existed in that quarter of the Pacific.

Thinking Geographically

Question

The Maori, indigenous Polynesian people in New Zealand, link their identity to specific “canoes,” or groups of ancestors, as they arrived in New Zealand. How does this system of identity support the idea that voyages to New Zealand were navigated rather than drift?

102

The relocation diffusion that produced the remarkable present distribution of the Polynesian languages has long been the subject of controversy. How, and by what means, could a traditional people have achieved the diffusion? Geolinguists Michael Levison, Gerard Ward, and John Webb answered these questions by developing a computer model incorporating data on winds, ocean currents, vessel traits and capabilities, island visibility, and duration of voyage. Both drift voyages, in which the boat simply floats with the winds and currents, and navigated voyages were considered.

After performing more than 100,000 voyage simulations, they concluded that the Polynesian triangle had probably been entered from the west, from the direction of the ancient Austronesian hearth area, in a process of islandhopping—that is, migrating from one island to another one visible in the distance. The core of eastern Polynesia was probably reached in navigated voyages, but once this was attained, drift voyages easily explain much of the internal diffusion. According to Levison and his colleagues, a peripheral region, the “outer arc from Hawaii through Easter Island to New Zealand,” could be reached only by means of intentionally navigated voyages: truly astonishing and daring feats (see Figure 4.8).

103

In carrying out their investigation, Levison and his colleagues employed the themes of region (present distribution of Polynesians) and cultural ecology (currents, winds, visibility of islands) to help describe and explain the workings of a third theme, cultural diffusion.

Language Proliferation: One or Many?

Language Proliferation: One or Many?

Using techniques that remain controversial, certain linguists are probing the origin and diffusion of languages, seeking elusive prehistoric tongues. Some scholars believe that an ancestral speech called Nostratic, spoken in the Middle East 12,000 to 20,000 years ago, was central to six modern language families: Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic, Afro-Asiatic, Caucasic, and Dravidian (see Figures 4.2 and 4.7). These linguists seek nothing less than the original linguistic hearth area, almost certainly in Africa, where complex speech first arose and from which it diffused. Skeptics counter that similarities among languages arose from coincidence or from speakers of one language borrowing words from others through trade and other cultural interactions.

104

Are the forces of modernization working to produce, through cultural diffusion, a single world language? If so, what will that language be? English? Worldwide about 328 million people speak English as their mother tongue and perhaps another 350 million speak it well as a second, learned language. Adding other reasonably competent speakers who can get by in English, the world total reaches about 1.5 billion, more than for any other language. What’s more, the Internet is one of the most potent agents of diffusion, and its language, overwhelmingly, is English.

English earlier diffused widely with the British Empire and U.S. imperialism, and today it has become the de facto language of globalization. Consider the case of India, where the English language imposed by British rulers was retained (after independence) as the country’s language of business, government, and education. It provided some linguistic unity for India, which had 800 indigenous languages and dialects. This is why today many of India’s nearly 1 billion people speak English well enough to provide customer support services over the telephone for clients in the United States. Even so, many people resent its use and wish India to be rid of this hated linguistic colonial legacy once and for all (see Figure 4.21). Although English is not likely to be driven out of India any time soon, it is true that the spoken English of India has drifted away from Standard British English. The same is true for the English of Singapore, which is now a separate language called Singlish. Many other region al English-based languages have developed, languages that could not be understood readily in London or Chicago.

But is the diffusion of English to the entire world population likely? Will globalization and cultural diffusion produce one world language? Probably not. More likely, the world will be divided largely among 5 to 10 major languages.

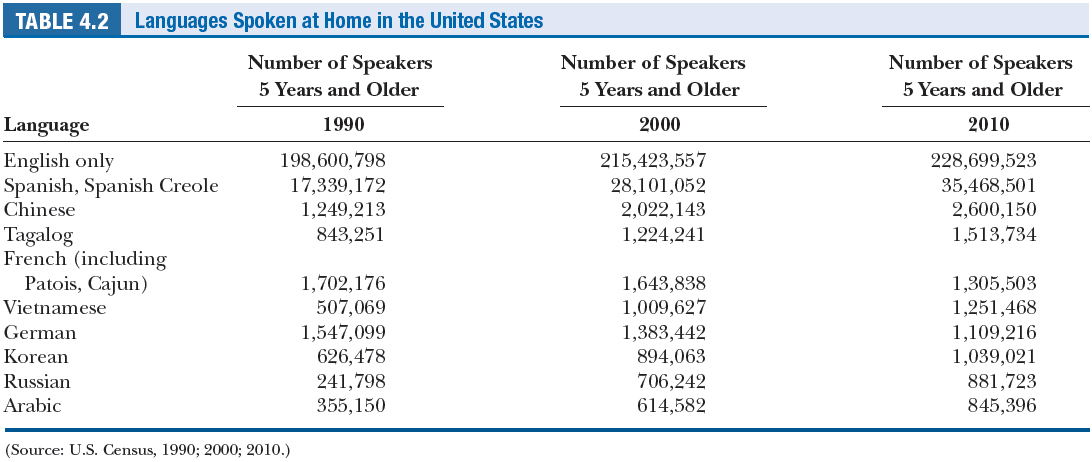

Despite the dominance of English in the United States and throughout much of the world in the twenty-first century, many other languages are spoken in American homes every day (Table 4.2). Examining the prominence of these various languages within the United States provides valuable insight into the presence of its different immigrant populations. Given that international migration trends fluctuate over time, it is not surprising that languages (other than English) spoken in American homes fluctuate from decade to decade. For example, by examining Table 4.2, we can see that the number of speakers of French and German in the United States has steadily declined since 1990. This trend will likely continue in future decades, as most families in the United States today that are of French or German descent can be traced to immigrants who came to the country during the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. Twenty-first century generations of these families have typically acquired English and begun using it as their first language. In contrast, Table 4.2 shows that speakers of Chinese and Arabic are on the increase in the United States since 1990. These trends reflect contemporary migration flows from Asia and the Middle East, as immigrants from these regions have more recently been drawn to the United States in search of economic and educational opportunities.

105