What are Race and Ethnicity?

What are Race and Ethnicity?

ethnicity See ethnic group.

race A classification system that is sometimes understood as arising from genetically significant differences among human populations, or visible differences in human physiognomy, or as a social construction that varies across time and space.

The word race is often used interchangeably with ethnicity, but the two have very different meanings, and one must be careful in choosing between the two terms. Race can be understood as a genetically significant difference among human populations. A few biologists today support the view that human populations do form racially distinct groupings, arguing that race explains phenomena such as the susceptibility to certain diseases. In contrast, many social scientists (and many biologists) have noted the fluidity of definitions of race across time and space, suggesting that race is a social construct rather than a biological fact (see Figures 5.4 and 5.5).

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why were such distinctions important when this painting was made? Why did Europeans find these matters so confusing at that time?

Thinking Geographically

Question

How is this idea of race as defined by visible differences different from race as it is commonly understood in the United States?

122

Because race is a social construction, it takes different forms in different places and times. In the United States of the early twentieth century, for example, the so-called one-drop rule meant that anyone with any African-American ancestry at all was considered black. This law was intended to prevent interracial marriage. It also meant that moving out of the category black was, and still is today, extremely difficult because one’s racial status is determined by ancestry. Yet the notion that “black blood” somehow makes a person completely black is challenged today by the growing numbers of young people with diverse racial backgrounds. The rise in interracial marriages in the United States and the fact that—for the first time in 2000—one could declare multiple races on the Census form mean that more and more people identify themselves as “racially mixed” or “biracial” instead of feeling they must choose only one facet of their ancestry as their sole identity. Thus, golfer Tiger Woods calls himself a “Cablinasian” to describe his mixed Caucasian, black, American Indian, and Asian background. Race and ethnicity arise from multiple sources: your own definition of yourself; the way others see you; and the way society treats you, particularly legally. All three of these are subject to change over time. Still, President Barack Obama, whose mixed-race ancestry has led him to identify with both his black and his white relatives, struggled during the 2008 presidential campaign with the claims that he was at once “too black” and “not black enough” to be a viable presidential candidate.

racism The belief that certain individuals are inferior because they are born into a particular ethnic, racial, or cultural group. Racism often leads to prejudice and discrimination, and it reinforces relationships of unequal power between groups.

Studies of genetic variation have demonstrated that there is far more variability within so-called racial groups than between them, which has led most scholars to believe that all human beings are, genetically speaking, members of only one race: Homo sapiens sapiens. In fact, many social scientists have dropped the term race altogether in favor of ethnicity. This is not to say, however, that racism, the belief that certain individuals are inferior because they are born into a particular ethnic, racial, or cultural group, does not exist. Indeed, it does exist, and often leads to attitudes of prejudice or acts of discrimination. It also reinforces relationships of unequal power between groups and/or individuals from differing ethno-cultural backgrounds. In this chapter, we use the verb racialize to refer to the processes whereby these socially constructed differences are understood—usually, but not always, by the powerful majority—to be impervious to assimilation. Across the world, hatreds based in racism are at the root of the most incendiary conflicts imaginable.

ethnic group A group of people who share a common ancestry and cultural tradition, often living as a minority group in a larger society.

What exactly is an ethnic group? The word ethnic is derived from the Greek word ethnos, meaning a people or nation, but that definition is too broad. For our purposes, an ethnic group consists of people of common ancestry and cultural tradition. A strong feeling of group identity characterizes ethnicity. Membership in an ethnic group is largely involuntary, in the sense that a person cannot simply decide to join; instead, he or she must be born into the group. In some cases, outsiders can join an ethnic group by marriage or adoption.

Reflecting on Geography

Question

Are ethnic groups always minorities, or do majority groups also have an ethnicity? What different sorts of traits might a majority group use to define its identity, as compared to a minority group? Is it possible for a racialized minority group to racialize other groups, or even itself?

Different ethnic groups may base their identities on different traits. For some, such as Jews, ethnicity primarily means religion; for the Amish, it is both folk culture and religion; for Swiss-Americans, it is national origin; for German-Americans, it is ancestral language; for African-Americans, it is a shared history stemming from slavery. Religion, language, folk culture, history, and place of origin can all help provide the basis of the sense of “we-ness” that underlies ethnicity.

As with race, ethnicity is a notion that is at once vexingly vague and hugely powerful. The boundaries of ethnicity are often fuzzy and shift over time. Moreover, ethnicity often serves to mark minority groups as different, yet majority groups also have an ethnicity, which may be based on a common heritage, language, religion, or culture. Indeed, an important aspect of being a member of the majority is the ability to decide how, when, and even if one’s ethnicity forms an overt aspect of one’s identity. Finally, some scholars question whether ethnicity even exists as intrinsic qualities of a group, suggesting instead that the perception of ethnic difference arises only through contact and interaction.

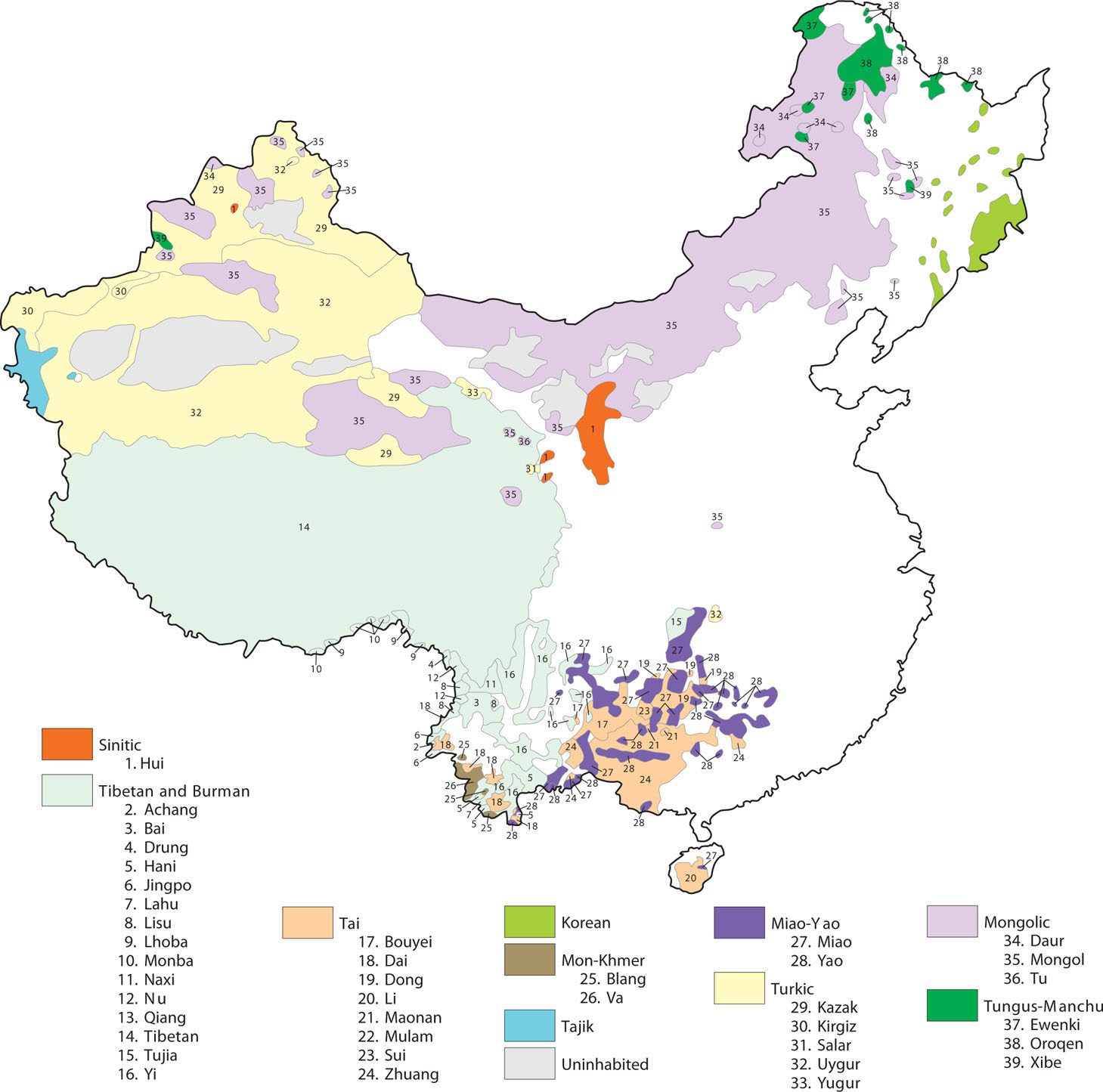

Apropos of this last point is the distinction between immigrant and indigenous (sometimes called aboriginal) groups. Many, if not most, ethnic groups around the world originated when they migrated from their native lands and settled in a new country. In their old home, they often belonged to the host culture and were not ethnic, but when they were transplanted by relocation diffusion to a foreign land, they simultaneously became a minority and ethnic. Han Chinese are not ethnic in China (Figure 5.6), but if they come to North America they are. Indigenous ethnic groups that continue to live in their ancient homes become ethnic when they are absorbed into larger political states. The Navajo, for example, reside on their traditional and ancient lands and became ethnic only when the United States annexed their territory. The same is true of Mexicans who, long resident in what is today the southwestern United States, found themselves labeled ethnic minorities when the border was moved after the 1848 U.S.–Mexican War. “We did not jump the border, the border jumped us!” is a common local comeback to this sudden shift in ethnic status.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Which of these ethnic regions are homelands and which are ethnic islands? Why are China’s ethnic groups concentrated in sparsely populated peripheries of the country?

123

acculturation The adoption by an ethnic group of enough of the ways of the host society to be able to function economically and socially.

assimilation The complete blending of an ethnic group into the host society, resulting in the loss of many or all distinctive ethnic traits.

This is not to say that ethnic minorities remain unchanged by their host culture. Acculturation often occurs, meaning that the ethnic group adopts enough of the ways of the host society to be able to function economically and socially. Stronger still is assimilation, which implies a complete blending with the host culture and may involve the loss of many or all distinctive ethnic traits. Intermarriage is perhaps the most effective way of encouraging assimilation. Many students of American culture have long assumed that all ethnic groups would eventually be assimilated into the American melting pot, but relatively few ethnic groups have been; instead they use acculturation as their way of survival. The past three decades, in fact, have witnessed a resurgence of ethnic identity across the globe.

ethnic geography The study of the spatial aspects of ethnicity.

Ethnic geography is the study of the spatial aspects of ethnicity. Ethnic groups are the keepers of distinctive cultural traditions and the focal points of various kinds of social interaction. They are the basis or source not only of group identity but also of friendships, marriage partners, recreational outlets, business success, and political power. These interactions can offer cultural security and reinforcement of tradition. Ethnic groups often practice unique adaptive strategies and usually occupy clearly defined areas, whether rural or urban. In other words, the study of ethnicity has built-in geographical dimensions. The geography of race is a related field of study that focuses on the spatial aspects of how race is socially constructed and negotiated. Cultural geographers who study race and ethnicity tend to always have an eye on the larger economic, political, environmental, and social power relations at work when race is involved. This chapter draws on insights and examples from both ethnic geography and the geography of race.

124