Ethnic Ecology

Ethnic Ecology

How do ethnic groups interact with their habitats? Is there a special bond between ethnic groups and the land they inhabit that helps to form their self-identity? Do ethnic groups find shelter in certain habitats? Are the areas inhabited by racialized groups targets of environmental racism? Ethnicity is very closely linked to cultural ecology. The possibilistic interplay between people and physical environment is often evident in the pattern of ethnic culture regions, in ethnic migration, and in ethnic persistence or survival. Ethnicity and race are sometimes also linked to the environment in harmful ways, particularly when the places they inhabit become the targets of pollution.

136

Cultural Preadaptation

Cultural Preadaptation

cultural preadaptation A set of adaptive traits and skills possessed in advance of migration by a group, giving it survival ability and competitive advantage in occupying the new environment.

For those ethnic groups created by migration or relocation diffusion, the concept of cultural preadaptation provides an interesting approach. Cultural preadaptation involves a set of adaptive traits possessed by a group in advance of migration that gives them the ability to survive and a competitive advantage in occupying the new environment. Most often, preadaptation occurs in groups migrating to a place environmentally similar to the one they left behind. The adaptive strategy they had pursued before migration works reasonably well in the new home.

The preadaptation may be accidental, but in some cases the immigrant ethnic group deliberately chooses a destination area that physically resembles their former home. In Africa, the Bantu expansion mentioned in Chapter 4 was probably initially driven by climate change and expansion of the Sahara (see Figure 4.4). The Bantu spread south and west in search of forested lands similar to those they had previously inhabited. Their progress southward was finally inhibited because their agricultural techniques and cattle were not adapted to the drier Mediterranean climate of southern Africa.

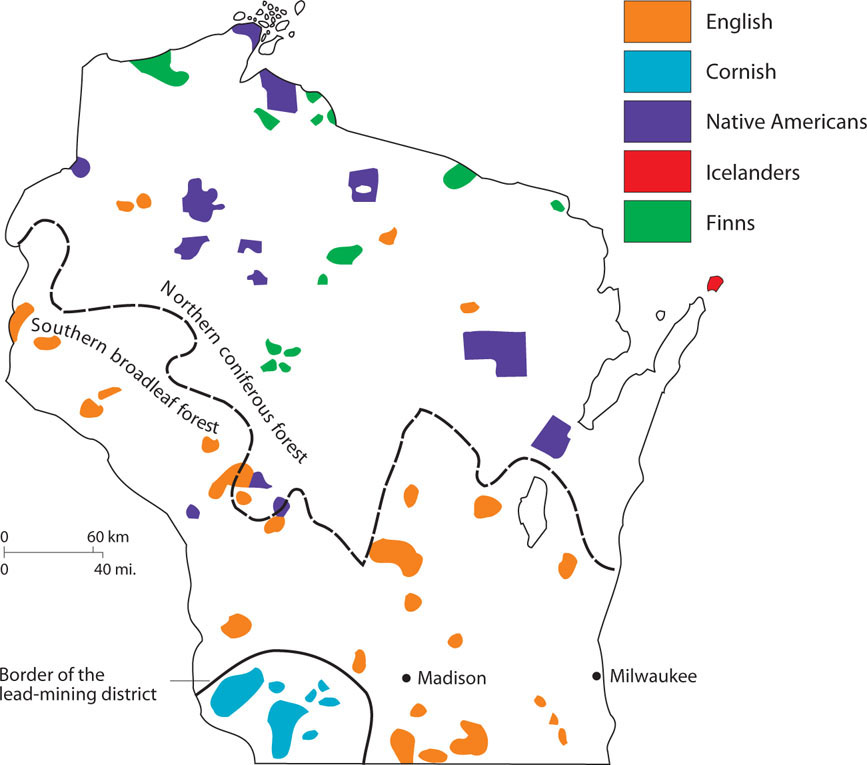

The state of Wisconsin, dotted with scores of ethnic islands, provides some fine examples of preadapted immigrant groups that sought environments resembling their homelands. Particularly revealing are the choices of settlement sites made by the Finns, Icelanders, English, and Cornish who came to Wisconsin (Figure 5.22). The Finns—coming from a cold, thin-soiled, glaciated, lake-studded, coniferous forest zone in Europe—settled the North Woods of Wisconsin, a land similar in almost every respect to the one from which they had migrated. Icelanders, from a bleak, remote island in the North Atlantic, located their only Wisconsin colony on Washington Island, an isolated outpost surrounded by the waters of Lake Michigan. The English, accustomed to good farmland, generally founded ethnic islands in the better agricultural districts of southern and southwestern Wisconsin. Cornish miners from the Celtic highlands of Cornwall in southwestern England sought out the lead-mining communities of southwestern Wisconsin, where they continued their traditional occupation.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why are the Finns concentrated in the northern coniferous forest region? The Native Americans?

Such ethnic niche-filling has continued to the present day. Cubans have clustered in southernmost Florida, the only part of the United States mainland to have a tropical savanna climate identical to that in Cuba, and many Vietnamese have settled as fishers on the Gulf of Mexico, especially in Texas and Louisiana, where they could continue their traditional livelihood. Yet historical and political patterns, as well as the factors driving chain migration discussed earlier, are also at work in these contemporary patterns of ethnic clustering. They act to temper the influence of the physical environment on ethnic residential selection, making it only one of many considerations.

cultural maladaptation Poor or inadequate adaptation that occurs when a group pursues an adaptive strategy that, in the short run, fails to provide the necessities of life or, in the long run, destroys the environment that nourishes it.

This deliberate site selection by ethnic immigrants represents a rather accurate environmental perception of the new land. As a rule, however, immigrants tend to perceive the ecosystem of their new home as more like that of their abandoned native land than is actually the case. Their perceptions of the new country emphasize the similarities and minimize the differences. Perhaps the search for similarity results from homesickness or an unwillingness to admit that migration has brought them to a largely alien land. Perhaps growing to adulthood in a particular kind of physical environment inhibits one’s ability to perceive a different ecosystem accurately. Whatever the reason, the distorted perception occasionally caused problems for ethnic farming groups. A period of trial and error was often necessary to come to terms with the New World environment. Sometimes crops that thrived in the old homeland proved poorly suited to the new setting. In such cases, cultural maladaptation is said to occur.

137

Habitat and the Preservation of Difference

Habitat and the Preservation of Difference

Certain habitats may act to shelter and protect ethnically or racially distinct populations. The high altitudes and rugged terrain of many mountainous regions make these areas relatively inaccessible and thus can provide refuge for minority populations while providing a barrier to outside influences. As we saw in Chapter 4 on language, mountain-dwellers sometimes speak archaic dialects or preserve their unique tongues thanks to the refuge provided by their habitat. In more general terms, the ways of life—including language—that are associated with ethnic distinctiveness are often preserved by a mountainous location.

The ethnic patchwork in the Caucasus region, for example, persists thanks in no small measure to the mountainous terrain found there. As Figure 5.23 shows, distinct groups occupy the rugged landscape of valleys, plateaus, peaks, foothills, steppes, and plains in this region. Religions and languages overlap in complex ways with ethnic identities and are made even more confounding by the geopolitical boundaries in this region, which do not necessarily follow the contours of the Caucasian ethnic mosaic. Thus, although this is one of the most ethnically diverse places on Earth, the Caucasus region has seen more than its fair share of conflict as well, much of it ethnically motivated.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why is this region one of almost perpetual conflict?

Islands, too, can provide a measure of isolation and protection for ethnically or racially distinct groups. The Gullah, or Geechee, people are descendants of African slaves brought to the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to work on plantations. Many of their nearly 10,000 descendants today inhabit coastal islands off South Carolina, Georgia, and north Florida. Their island location has allowed many of their original African cultural roots to be preserved, so much so that the Gullah are sometimes called the most African-American community in the United States. Today, as the tourist industry sets its sights on developing these coastal islands, and as Gullah youth migrate elsewhere in search of opportunity, the survival of this unique culture is in question.

138

Environmental Racism

Environmental Racism

Not only people but also the places where they dwell can be labeled by society as minority. It is a fact that, although belonging to a racial or ethnic minority group does not necessarily lead to poverty, the two often go hand-in-hand. In spatial terms, being poor frequently means having the last and worst choice of where to live. In cities, that means impoverished and racialized minorities often reside in run-down, ecologically precarious, or peripheral places that no one else wants to inhabit (Figure 5.24). In rural areas, racialized and indigenous minorities work the smallest and least-fertile lands, or—more commonly—they work the plots of others, having been dispossessed of their own lands.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What parallels to this neighborhood can you think of in your community or country?

environmental racism The targeting of areas where ethnic or racial minorities live with respect to environmental contamination or failure to enforce environmental regulations.

Environmental racism refers to the likelihood that a racialized minority population inhabits a polluted area. As Robert Bullard asserts, “Whether by conscious design or institutional neglect, communities of color in urban ghettos, in rural ‘poverty pockets,’ or on economically impoverished Native American reservations face some of the worst environmental devastation in the nation.” In the United States, Hispanics, Native Americans, and blacks are more likely than whites to reside in places where toxic wastes are dumped, polluting industries are located, or environmental legislation is not enforced. Inner-city populations, which in many U.S. cities are disproportionately made up of minorities, occupy older buildings contaminated with asbestos and toxic lead-based paints. Farm workers, who in the United States are disproportionately Hispanic, are exposed to high levels of pesticides, fertilizers, and other agricultural chemicals. Native American reservation lands are targeted as possible sites for disposing of nuclear waste.

139

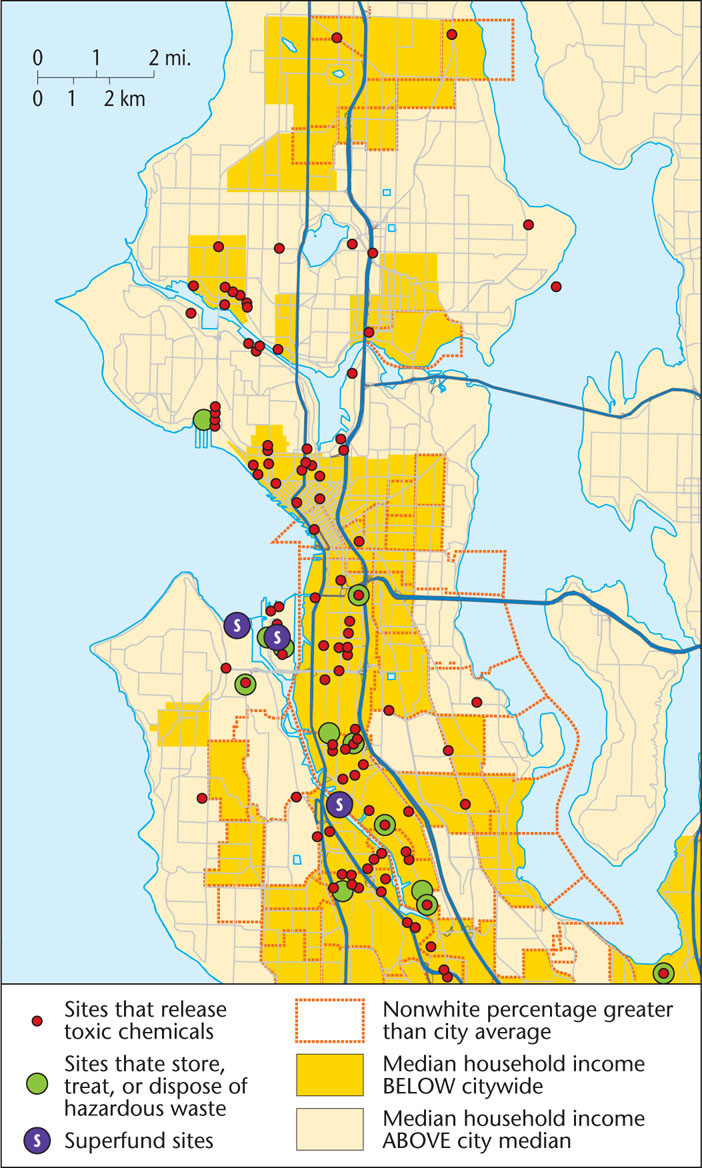

As Figure 5.25 depicts, in the Seattle area there is an overlap of nonwhite (and low-income) populations with hazardous waste storage, treatment, and disposal facilities, as well as facilities that release toxic chemicals into the surrounding environment. This association is difficult to explain away as simply a random coincidence. Rather, it appears that contaminating industries and activities purposely located in neighborhoods composed of largely nonwhite residents and residents with incomes below the median level.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What other kinds of facilities may be located near minority or poor populations?

Environmental racism extends to the global scale. Industrial countries often dispose of their garbage, industrial waste, and other contaminants in poor countries. Industries headquartered in wealthy nations often outsource the dangerous and polluting phases of production to countries that do not have—or do not enforce—strict environmental legislation. Whether areas inhabited by poor, ethnic, or racialized minorities are deliberately targeted for unhealthy conditions, or whether they are simply the unfortunate recipients of the effects of larger detrimental processes, the connections among race, ethnicity, and the environment pose central questions for cultural geographers.