Ethnic Landscapes

Ethnic Landscapes

ethnic flag A readily visible marker of ethnicity on the landscape.

What traces do ethnicity and race leave on the landscape? Ethnic and racialized landscapes often differ from mainstream landscapes in the styles of traditional architecture, in the patterns of surveying the land, in the distribution of houses and other buildings, and in the degree to which they “humanize” the land. Often the imprint is subtle, discernible only to those who pause and look closely. Sometimes it is quite striking, flaunted as an ethnic flag: a readily visible marker of ethnicity on the landscape that strikes even the untrained eye (Figure 5.29). Sometimes the distinctive markers of race and ethnicity are not visible at all but rather are audible, tactile, olfactory, or—as we explore here with culinary landscapes—tasty.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why would a facility for storage of corn remain an indicator of indigenous ethnicity?

Urban Ethnic Landscapes

Urban Ethnic Landscapes

Ethnic cultural landscapes often appear in urban settings, in both neighborhoods and ghettos. A fine example is the brightly colored exterior mural typically found in Mexican-American ethnic neighborhoods in the southwestern United States (Figure 5.30). These began to appear in the 1960s in Southern California, and they exhibit influences rooted in both the Spanish and the indigenous cultures of Mexico, according to geographer Daniel Arreola. A wide variety of wall surfaces, from apartment house and store exteriors to bridge abutments, provide the space for this ethnic expression. The subjects portrayed are also wide ranging, from religious motifs to political ideology, from statements about historical wrongs to ones about urban zoning disputes. Often they are specific to the site, incorporating well-known elements of the local landscape and thus heightening the sense of place and ethnic turf. Inscriptions can be in either Spanish or English, but many Mexican murals do not contain a written message, relying instead on the sharpness of image and vividness of color to make an impression.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What Mexican and Mexican-American symbols can you pick out in the mural?

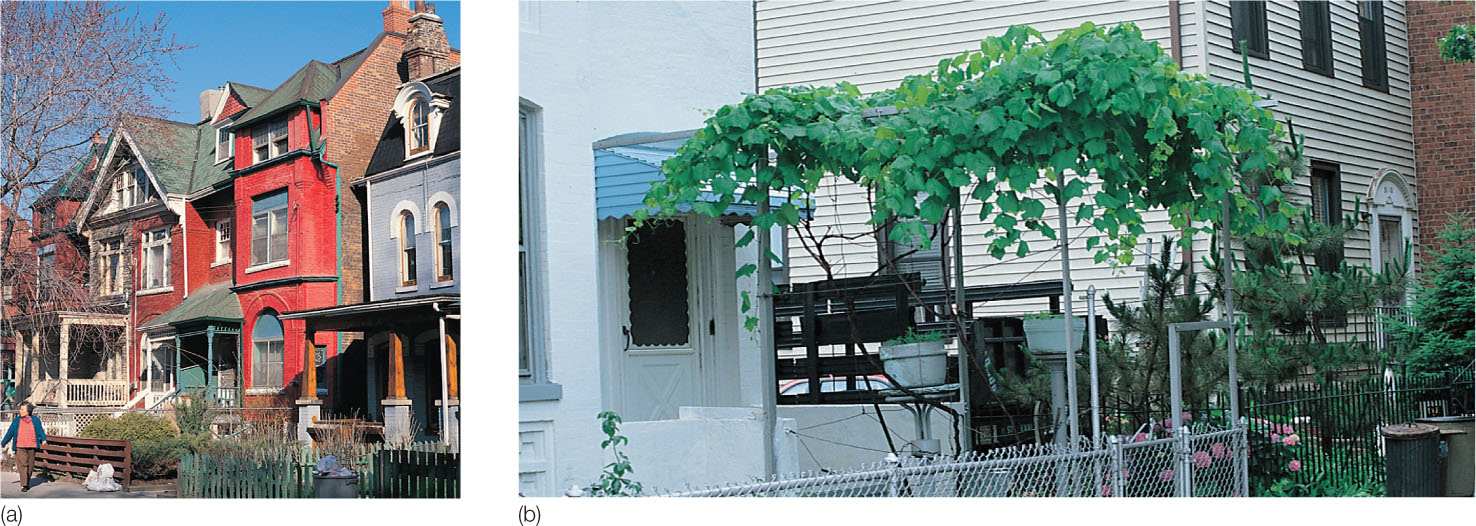

Usually, the visual ethnic expression is more subtle. Color alone can connote and reveal ethnicity to the trained eye. Red, for example, is a venerated and auspicious color to the Chinese, and when they established Chinatowns in Canadian and American cities, red surfaces proliferated (Figure 5.31). Light blue is a Greek ethnic color, derived from the flag of their ancestral country. Not only that, but Greeks also avoid red, which is perceived as the color of their ancient enemy, the Turks. Green, an Irish Catholic color, also finds favor in Muslim ethnic neighborhoods in countries as far-flung as France and China because it is the sacred color of Islam (see chapter 7).

Thinking Geographically

Question

Would such ethnic expression be permitted in a new residential development with a neighborhood or homeowners’ association set up by the developer? Why?

143

Indeed, urban ethnic and racial landscapes are visible in cities around the world. This is true even when urban planners try their best to prevent the emergence of such landscapes. When Brazil’s capital was moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília in 1960, for example, very few pedestrian-friendly public spaces were incorporated into the urban plan of architects Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer. Rather, residences were concentrated in high-rise apartments called superquadra; streets were designed for high-speed motor traffic only; and no smaller plazas, cafés, or sidewalks were included—all of which discouraged informal socialization (Figure 5.32). As historian James C. Scott notes in his discussion of Brasília, the lack of human-scale public gathering places was intentional. “Brasília was to be an exemplary city, a center that would transform the lives of the Brazilians who lived there—from their personal habits and household organization to their social lives, leisure, and work. The goal of making over Brazil and Brazilians necessarily implied a disdain for what Brazil had been.” But because the housing needs of those building the city and serving the government workers had not been planned, Brasília soon developed surrounding slums that did not follow an orderly layout. And because the desires of wealthier residents were not met by the uniform superquadra apartments, unplanned but luxurious residences and private clubs were also built. By 1980, 75 percent of Brasília’s population lived in unanticipated settlements.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What message were the plan and architecture meant to convey?

144

The Re-creation of Ethnic Cultural Landscapes

The Re-creation of Ethnic Cultural Landscapes

As mentioned previously in this chapter, migration is the principal way that groups that were not ethnic in their homelands become ethnic or racialized, through relocation to a new place. As we have seen, ethnic groups may choose to relocate to places that remind them of their old homelands. Once there, they set about re-creating some—although, because of cultural simplification, not all—particular landscapes in their new homes.

Cuban-American immigrants, for example, have reconstructed aspects of their prerevolutionary Cuban homeland in Miami. In the early 1960s, the first wave of Cuban refugees came to the United States on the heels of Castro’s communist revolution on the island. Some went north, to places such as Union City, New Jersey, where today there is a sizable Cuban-American population. Others, however, came (or eventually relocated) to Miami. Once a predominantly Jewish neighborhood called Riverside, what is today called the Little Havana neighborhood became the heart of early Cuban immigration. Shops along the main thoroughfare, Calle Ocho (or Southwest Eighth Street), reflect the Cuban origins of the residents: grocers such as Sedanos and La Roca cater to the Spanish-inspired culinary traditions of Cuba; cafés selling small cups of strong, sweet café Cubano exist on every block; and famed restaurants such as Versailles are social gathering points for Cuban-Americans.

Because ethnicity and its expression on the landscape are fluid and ever-changing, the landscape of Calle Ocho reflects the current demographic changes under way in Little Havana. Although the neighborhood is still a Latino enclave, with a Hispanic population in excess of 95 percent, not even half of its population self-identified as Cuban in the 2010 Census. More than one-quarter of Little Havana’s residents are recent arrivals from Central American countries, particularly Nicaragua and Honduras, whereas more and more Argentineans and Colombians are arriving—like the Cubans before them—on the heels of political and economic chaos in their home countries. Today, you are just as likely to see a Nicaraguan fritanga restaurant as a Cuban coffee shop along Calle Ocho. This has prompted some to suggest that the neighborhood’s name be changed from Little Havana to The Latin Quarter.

Another example of a re-created ethnic landscape can be found in Washington, D.C. Beginning in the 1970s, large numbers of Ethiopian emigrants, fleeing a repressive government and impoverished conditions, relocated from their homeland to the United States. With changes in American immigration restrictions and the introduction of new refugee programs during the 1980s and 1990s, flows of Ethiopian migrants to the United States continued. Disproportionate numbers of these Ethiopian migrants (when compared to other American cities) settled in the greater Washington, D.C., area. Once there, they began to re-create many aspects of the cultural landscape of their homeland in their newly adopted country. For example, Figure 5.33 depicts a Washington, D.C., neighborhood where a concentration of Ethiopian businesses and restaurants sprang up and grew in the area of Ninth and U streets. At the request of Ethiopian residents in this neighborhood, it has even been signposted “Little Ethiopia” by District officials. Culinary tours to Washington, D.C., now often include stops in this area so that visitors may partake of the many specialty foods on offer and shop in the neighborhood’s vibrant food markets, clothing stores, and music shops.

Thinking Geographically

Question

In what other ways might the influx of Ethiopian immigrants be seen or sensed on the cultural landscape of Washington, D.C.?

145

It is not merely the presence of Ethiopian flags, fashions, and signage in native languages on brightly painted storefronts that signify the presence of a re-created cultural landscape in Little Ethiopia, however. Geographer Elizabeth Chacko has studied the making of ethnic places in Washington, D.C., and found that Ethiopian migrants have also re-created aspects of their native culture by participating in entrepreneurial endeavors in their new home. An entrepreneurial spirit is much admired among Ethiopians, and they have impressed this aspect of their culture on the landscape of their new home. The entrepreneurial spirit is particularly evidenced by one city block of Little Ethiopia, which is now home to more than 25 businesses started and run by Ethiopian migrants. In fact, many Ethiopian families own more than one business in the neighborhood and have also expanded their entrepreneurship outward into other areas of Washington, D.C. A telephone directory of Ethiopian-owned businesses in the District now includes over 900 listings. In the twenty-first century, the Ethiopian entrepreneurial spirit continues to diffuse with such contagion that a second (unofficial) Little Ethiopia has now sprung up across the Potomac River in Alexandria, Virginia.

Ethnic Culinary Landscapes

Ethnic Culinary Landscapes

foodway Customary behavior associated with food preparation and consumption.

“Tell me what you eat, and I’ll tell you who you are.” This oft-quoted phrase arises from the connections between identity and foodways, or the customary behaviors associated with food preparation and consumption that vary from place to place and from ethnic group to ethnic group. As geographers Barbara and James Shortridge point out, “Food is a sensitive indicator of identity and change.” Immigration, intermarriage, technological innovation, and the availability of certain ingredients mean that modifications and simplifications of traditional foods are inevitable over time. An examination of culinary cultural landscapes reveals that, although landscapes are typically understood to be visual entities, they can be constructed from the other four senses as well: touch, smell, sound, and—in this case—taste.

Constituting part of the rich Southern culinary landscape in the United States is a regionalized foodway tradition known as Cajun cooking. The practices associated with Cajun cooking began as far back as the 1700s. At that time, American Indians, Arcadians (an exiled group from Canada), and other immigrant populations coming to the South (including Germans, French, English, Creoles, Africans, and Mexicans) began to blend their cooking practices and traditional ingredients to develop new Cajun foodways. These immigrant groups were often poor and had to make do with inexpensive and easily accessible ingredients. As a result, they began the practice of adding spices to these otherwise bland or simple foods to produce the characteristic Cajun kick that has become so popular throughout the South and many other parts of the United States today. Figure 5.34 depicts one popular Cajun dish, crawfish pie, which blends locally caught crawfish and crabs with rice, beans, and spicy Cajun sausage.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What other American foodways can you think of that blend food practices and traditional ingredients from two or more cultures?

Another example of a regional foodway that has become a fixture in the contemporary American cultural landscape is traceable to traditional Mexican cooking practices. In many regions of Mexico, corn was traditionally ground daily to make fresh tortillas, which were used as the staple “bread” component in most meals. However, the grinding of corn is strenuous and time-consuming. Therefore, over time, corn tortillas began to be replaced with wheat tortillas, which are easier to make. As Mexican immigrants began to spread through the southwestern United States and other areas, they took these modified foodways with them. As a result of this diffusion, we now find wheat tortillas embedded in many U.S. fast foods (such as wraps) and home-cooked dishes.

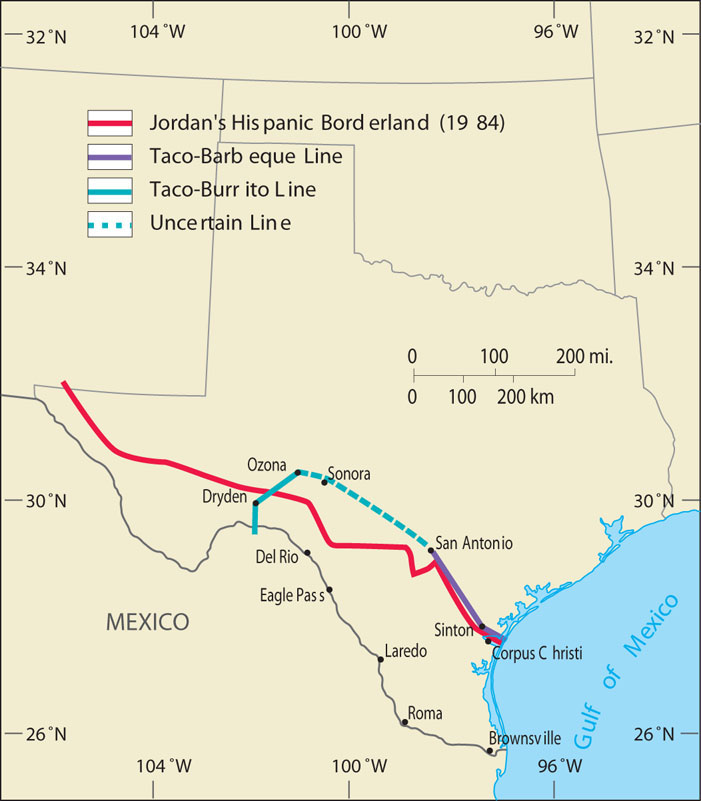

Geographer Daniel Arreola has plotted the Taco-Burrito and the Taco-Barbeque isoglosses in southwestern Texas in Figure 5.35. These lines show the transition between different Mexican culinary influences (tacos versus burritos) and between Mexican and European foodways (tacos versus barbeque), with the barbeque sandwich preferred by the German, Czech, Scandinavian, Anglo, and black Texan populations to the north and east of the line.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Thinking of restaurants in your area serving Mexican food, what kinds of tacos or burritos are most common? Is there a distance-decay force at work?

146