Political Culture Regions

Political Culture Regions

How is political geography revealed in culture regions? The theme of culture region is essential to the study of political geography because an array of both formal and functional political regions exist. Among these, the most important and influential is the state.

150

A World of States

A World of States

state An independent political unit with a centralized authority that makes claims to sole jurisdiction over a bounded territory, within which a central authority controls and enforces a single system of political and legal institutions; often used synonymously with “country.”

sovereignty The right of individual states to control political and economic affairs within their territorial boundaries without external interference.

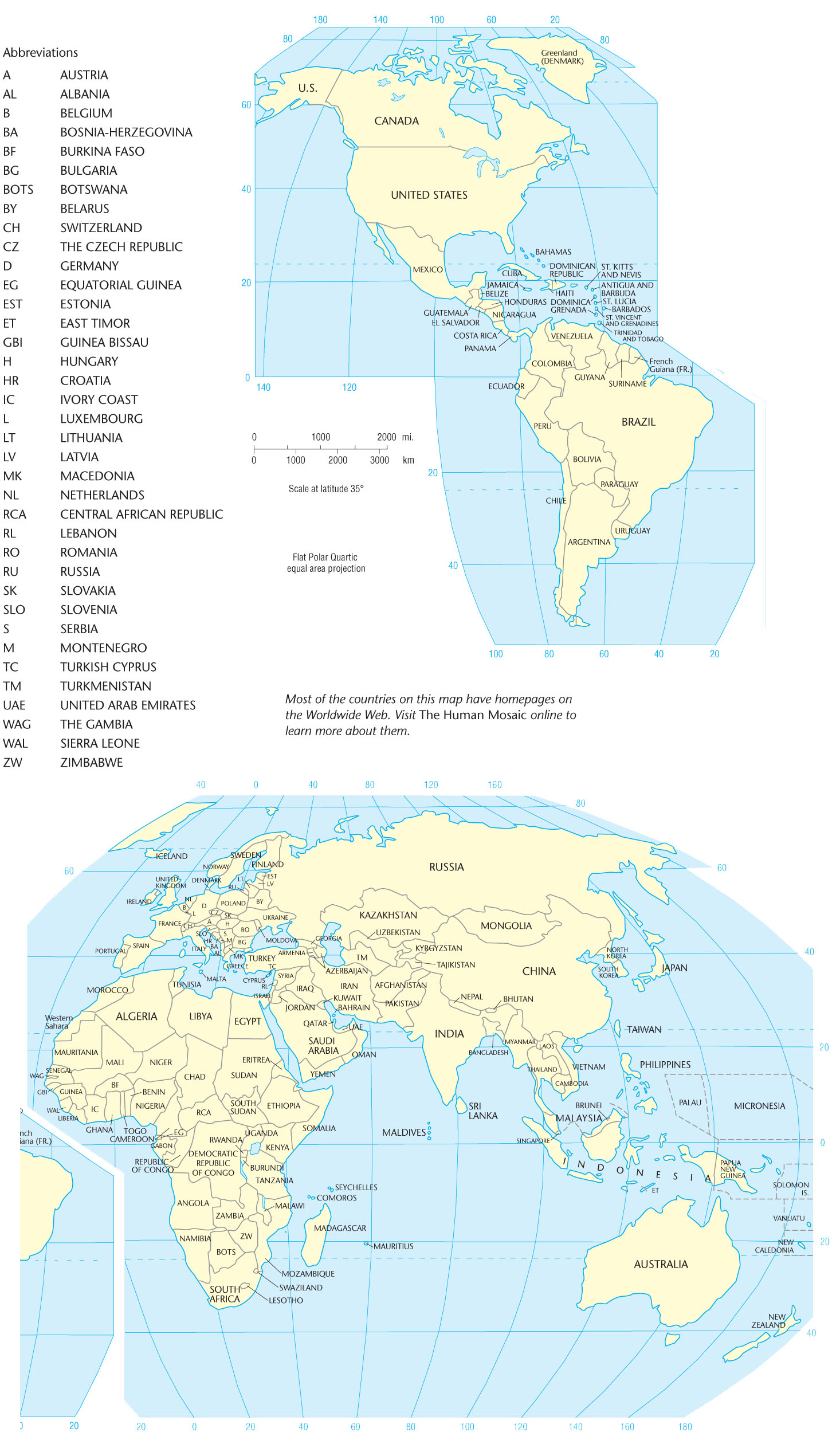

The fundamental political-geographical fact is that Earth is divided into nearly 200 independent countries or states, creating a diverse mosaic of functional regions (Figure 6.1). The state is a political institution that has taken a variety of forms over the centuries, ranging from Greek city-states to Chinese dynastic states to European feudal states. When we talk about states today, however, we mean something very specific and historically recent. States are independent political units with a centralized authority that makes claims to sole jurisdiction over a bounded territory. Within that territory, the central authority controls and enforces a single system of political and legal institutions. Importantly, in the modern international system, states recognize each other’s sovereignty. That is, virtually every state recognizes every other state’s right to exist and control its own affairs within its territorial boundaries.

Independent Countries

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.1

What changes might take place next?

151

Closer inspection of Figure 6.1 reveals that some parts of the world are fragmented into many states, whereas others exhibit much greater unity. The United States occupies about the same amount of territory as Europe, but the latter is divided into 45 independent countries. The continent of Australia is politically united, whereas South America has 12 independent entities and Africa has more than 50.

152

territoriality A learned cultural response, rooted in European history, that produced the external bounding and internal territorial organization characteristic of modern states.

colonialism The building and maintaining of colonies in one territory by people based elsewhere; the forceful appropriation of a territory by a distant state, often involving the displacement of indigenous populations to make way for colonial settlers.

The modern state is a tangible geographical expression of one of the most common human tendencies: the need to belong to a larger group that controls its own piece of Earth, its own territory. So universal is this trait that scholars coined the term territoriality to describe it. Most geographers view territoriality as a learned cultural response. Robert Sack, for example, regards territoriality as a cultural strategy that uses power to control an area and communicate that control, thereby subjugating the inhabitants and acquiring resources. He argues that the precise marking of borders is a practice unique to modern Western culture. The modern territorial state, he claims, emerged rather recently in sixteenth-century Europe and diffused around the globe through European colonialism. Colonialism is the building and maintaining of colonies in one territory by people based elsewhere; it is the forceful appropriation of a territory by a distant state, often involving the displacement of indigenous populations to make way for colonial settlers.

Political territoriality, then, is a thoroughly cultural-geographical phenomenon. The sense of collective identity that we call nationalism (see page 155) springs from a learned or acquired attachment to region and place. Geography and national identity cannot be separated.

Distribution of National Territory

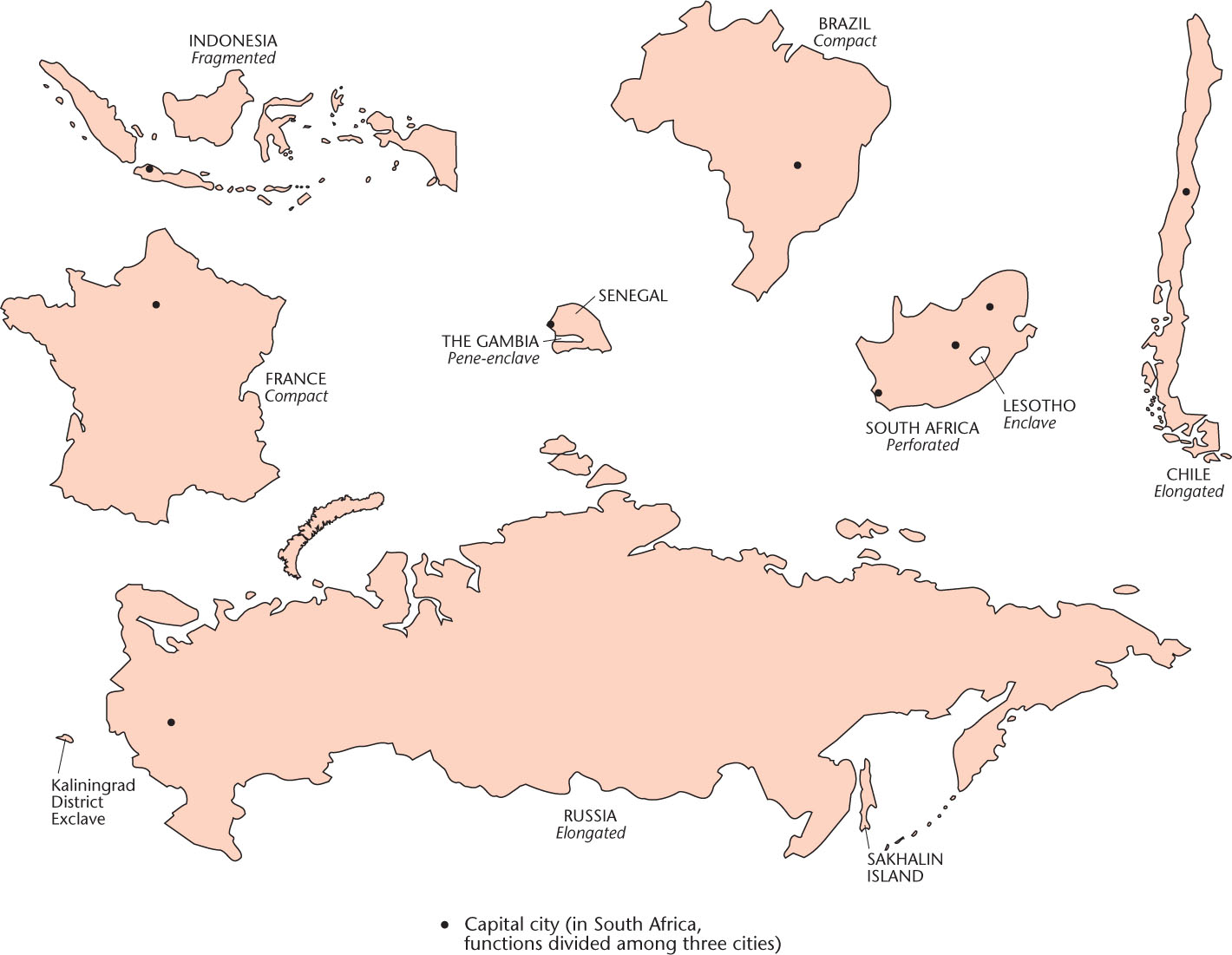

Distribution of National Territory An important geographical aspect of the modern state is the shape and configuration of the national territory. Theoretically, the more compact the territory, the easier is national governance. Circular or hexagonal forms maximize compactness, allow short communication lines, and minimize the amount of border to be defended. Of course, no country actually enjoys this ideal degree of compactness, although some—such as France and Brazil—come close (Figure 6.2).

enclave A piece of territory surrounded by, but not part of, a country.

exclave A piece of national territory separated from the main body of a country by the territory of another country.

An enclave is a piece of territory surrounded by, but not part of, a country. For example, Lesotho is an enclave that is completely surrounded by South Africa. Exclaves are parts of a national territory separated from the main body of the country to which they belong by the territory of another (e.g., the Kaliningrad District in Figure 6.2). Exclaves are particularly undesirable if a hostile power holds the intervening territory because defense of such an isolated area is difficult and makes substantial demands on national resources. Moreover, an exclave’s inhabitants, isolated from their compatriots, may develop separatist feelings, thereby causing additional problems.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.2

What problems can arise from elongation, enclaves, fragmentation, and exclaves?

Pakistan provides a good example of the national instability created by exclaves. Pakistan was created in 1947 as two main bodies of territory separated from each other by almost 1000 miles (1600 kilometers) of territory in northern India. West Pakistan had the capital and most of the territory, but East Pakistan was home to most of the people. West Pakistan hoarded the country’s wealth, exploiting East Pakistan’s resources but giving little in return. Ethnic differences between the peoples of the two sectors further complicated matters. In 1971, a quarter of a century after its founding, Pakistan broke apart. The distant exclave seceded and became the independent country of Bangladesh (see Figure 6.1).

Even when a national territory is geographically united, instability can develop if the shape of the state is awkward. Narrow, elongated countries, such as Chile, The Gambia, and Norway, can be difficult to administer, as can nations consisting of separate islands (see Figures 6.1 and 6.2). In these situations, transportation and communications are difficult, causing administrative problems. Several major secession movements threaten the multi-island country of Indonesia; one of these—in East Timor—recently succeeded. Similarly, the three-island country of Comoros, in the Indian Ocean, is troubled today by a separatist movement on Anjouan Island.

The shape and configuration of a country can make it harder or easier to administer, but it does not determine its stability. We can think of exceptions for all of the territorial forms in Figure 6.2 . For example, Alaska is an exclave of the United States, but it is unlikely to produce a secessionist movement similar to that of Bangladesh. Conversely, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria both have compact territories and both have suffered through secessionist wars. Geography is an important factor in national governance, but it is not the only factor.

Boundaries

buffer state An independent but small and weak country lying between two powerful countries.

satellite state A small, weak country dominated by one powerful neighbor to the extent that some or much of its independence is lost.

Boundaries Political territories have different types of boundaries. Until fairly recent times, many boundaries were not sharp, clearly defined lines but instead were referred to as zones called marchlands. Today, the nearest equivalent to the marchland is the buffer state, an independent but small and weak country lying between two powerful, potentially belligerent countries. Mongolia, for example, is a buffer state between Russia and China; Nepal occupies a similar position between India and China (see Figure 6.1). If one of the neighboring countries assumes control of the buffer state, it loses some or much of its independence and becomes a satellite state.

153

natural boundary A political border that follows some feature of the natural environment, such as a river or mountain ridge.

ethnographic boundary A political border that follows some cultural border, such as a linguistic or religious border.

geometric boundary A political border drawn in a regular, geometric manner, often a straight line, without regard for environmental or cultural patterns.

Most modern boundaries are lines rather than zones, and we can distinguish several types. Natural boundaries follow some feature of the natural landscape, such as a river or mountain ridge. Examples of natural boundaries are numerous; for example, the Pyrenees lie between Spain and France, and the Rio Grande serves as part of the border between Mexico and the United States. Ethnographic boundaries are drawn on the basis of some cultural trait, usually a particular language spoken or religion practiced. The border that divides India from predominantly Islamic Pakistan is one case. Geometric boundaries are regular, often perfectly straight lines drawn without regard for physical or cultural features of the area. The U.S.–Canada border west of the Lake of the Woods (about 93° west longitude) is a geometric boundary, as are most county, state, and province borders in the central and western United States and Canada. Not all boundaries are easily categorized; some boundaries are of mixed type, composites of two or more of the types listed.

154

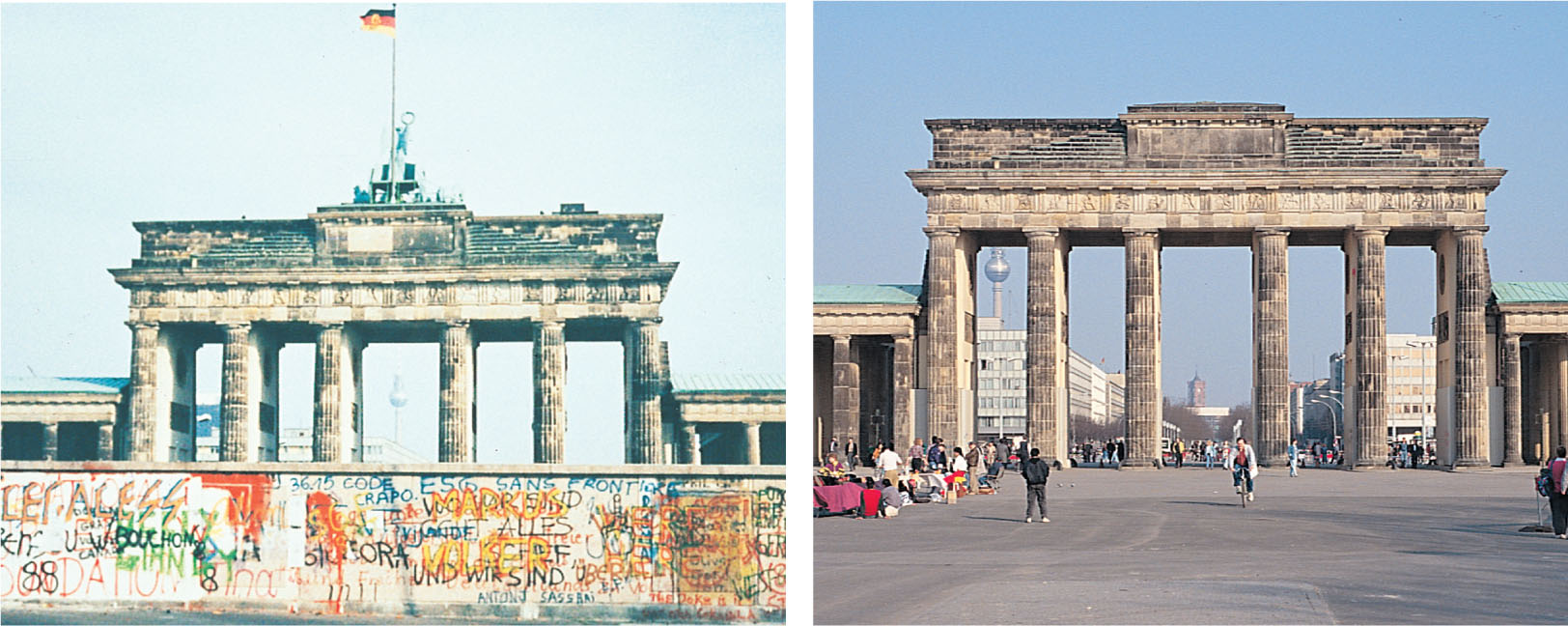

relic boundary A former political border that no longer functions as a boundary.

Finally, relic boundaries are those that no longer exist as international borders. Nevertheless, they often leave behind a trace in the local cultures. With the reunification of Germany in the autumn of 1990, the old Iron Curtain border between the former German Democratic Republic in the east and the Federal Republic of Germany in the west was quickly dismantled (Figure 6.3). In a remarkably short time span, measured in weeks, the Germans reopened severed transport lines and created new ones, knitting the enlarged country together. Even so, remnants and reminders of the old border remained, as it continued to function as a provincial boundary within Germany. Furthermore, it still separated two parts of the country with strikingly different levels of prosperity.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.3

Do you think the walls between Israel and the West Bank and between the United States and Mexico will someday be torn down? Why or why not?

Spatial Organization of Territory

unitary state An independent state that concentrates power in the central government and grants little authority to the provinces.

federal state An independent country that gives considerable powers and even autonomy to its constituent parts.

Spatial Organization of Territory States differ greatly in the way their territory is organized for purposes of administration. Political geographers recognize two basic types of spatial organization: unitary and federal. In unitary countries, power is concentrated centrally, with little or no provincial authority. All major decisions come from the central government, and policies are applied uniformly throughout the national territory. France and China are unitary in structure, even though one is democratic and the other totalitarian. A federal government, by contrast, is a more geographically expressive political system. That is, it acknowledges the existence of regional cultural differences and provides the mechanism by which the various regions can perpetuate their individual characters. Power is diffused, and the central government surrenders much authority to the individual provinces. The United States, Canada, Germany, Australia, and Switzerland, though exhibiting varying degrees of federalism, provide examples. The trend in the United States has been toward a more unitary, less federal government, with fewer states’ rights. By contrast, federalism remains vital in Canada, representing an effort to counteract French-Canadian demands for Québec’s independence. That is, by emphasizing federalism, the central government allows more latitude for provincial self-rule, thus reducing public support for the more radical option of secession.

Whether federal or unitary, a country functions through some system of political subdivisions. In federal systems, these subdivisions sometimes overlap in authority, with confusing results. For example, the Native American reservations in the United States occupy a unique and ambiguous place in the federal system of political subdivisions. These semiautonomous enclaves are legally sanctioned political territories that theoretically only indigenous Americans can possess. In reality, ownership is often fragmented by non-Native American land holdings within the reservations. Although not completely sovereign, Native Americans do have certain rights to self-government that differ from those of surrounding local authorities. For example, many reservations can (and do) build casinos on their land even though gambling may be illegal in surrounding political jurisdictions. Reservations do not fit neatly into the American political system of states, counties, townships, precincts, and incorporated municipalities.

155

Centrifugal and Centripetal Forces

Centrifugal and Centripetal Forces Although physical factors such as the spatial organization of territory, degree of compactness, and type of boundaries can influence an independent country’s stability, other forces are also at work. In particular, cultural factors often make or break a country. The most viable independent countries, those least troubled by internal discord, have a strong feeling of group solidarity among their population. Group identity is the key.

nationalism The sense of belonging to and self-identification with a national culture.

In the case of the modern state, the primary source of group identity is nationalism. Nationalism is the idea that the individual derives a significant part of his or her social identity from a sense of belonging to a nation. We can trace the origins of modern nationalism to the late eighteenth century and the emergence of the modern nation-state. Political geographer John Agnew cautions us, however, that the meaning and form of nationalism are unstable, making it difficult to generalize. One version is state nationalism, wherein the nation-state is exalted and individuals are called to sacrifice for the good of the greater whole. The twentieth-century history of state nationalism in Europe is marked by two horrific world wars in which millions of lives were sacrificed. Referring to World War I, Agnew points out that the “war itself was also the outcome of a mentality in which the individual person had to sacrifice for the good of the greater whole: the nation-state.” Another form is sub-state nationalism, in which ethnic or linguistic minority populations seek to secede from the state or to alter state territorial boundaries to promote cultural homogeneity and political autonomy.

centripetal force Any factor that supports the internal order of a country.

centrifugal force Any factor that disrupts the internal order of a country.

Geographers refer to factors that promote national unity and solidarity as centripetal forces. By contrast, anything that disrupts internal order and furthers the destruction of the country is called a centrifugal force. Many states encourage centripetal forces that help fuel nationalistic sentiment. Such things as an official national language, national history museums, national parks and monuments, and sometimes even a national religion are actively promoted and supported by the state. We consider an array of centripetal and centrifugal forces later, in the section on cultural ecology.

6.0.1 International Political Bodies

International Political Bodies

international organization A general term used to describe varying types of organizations that attempt to promote cooperation and coordination among their member states.

supranationalism Occurs when states willingly relinquish some degree of sovereignty in order to gain the benefits of belonging to a larger political-economic entity.

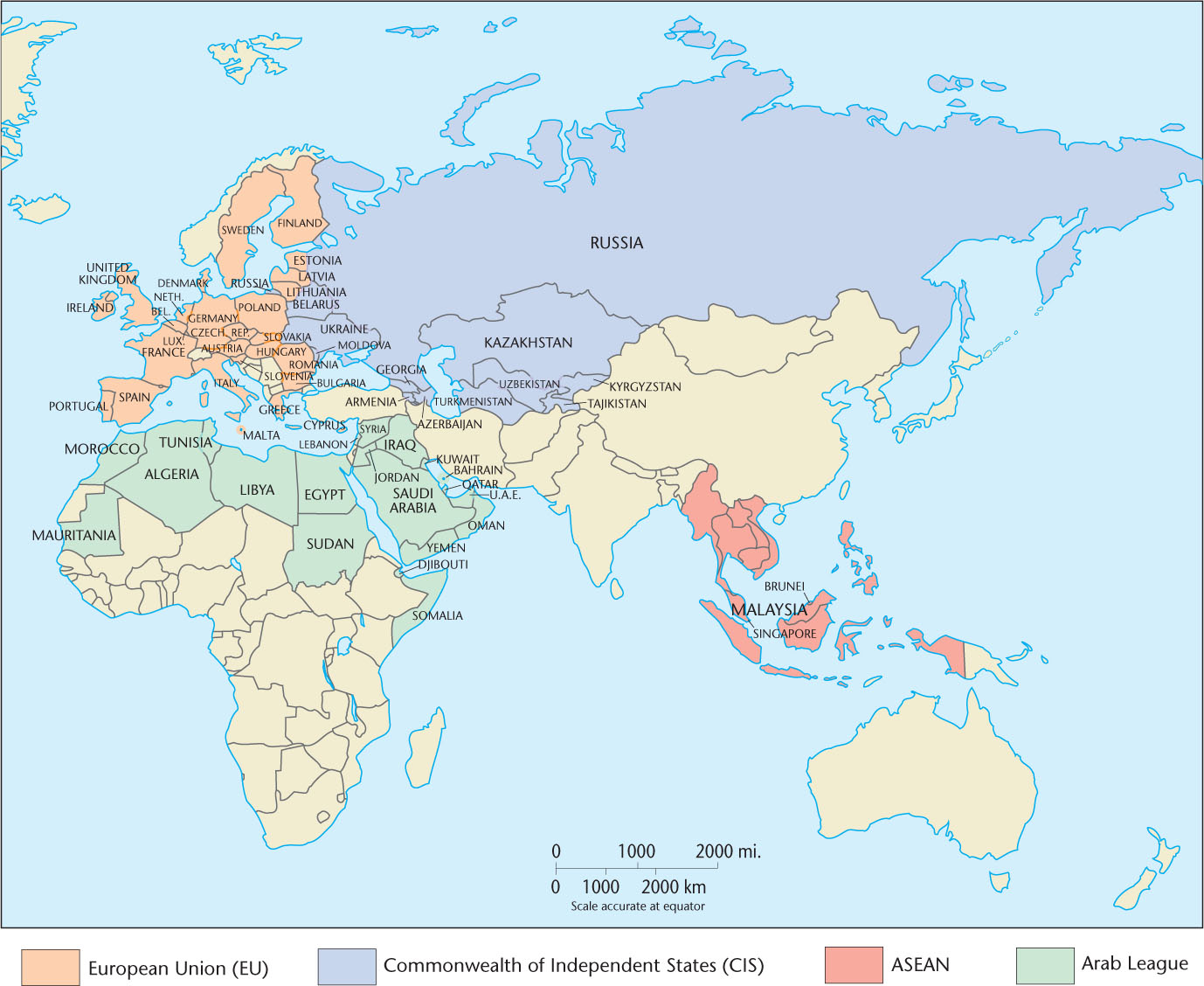

European Union (EU) A supranational organization composed of 27 European nations.

In addition to independent countries and their governmental subdivisions, the third major type of political functional region is the international organization. This term is often loosely used to describe varying types of organizations that attempt to promote cooperation and coordination amongst their member states. However, key functional differences can be used to more specifically classify international organizations as intergovernmental organizations or supranational organizations. Examples of both types of organizations are shown in Figure 6.4. Supranationalism exists when countries voluntarily give up some portion of their sovereignty to gain the advantages of a closer political, economic, and cultural association with their neighbors. The only organization that is currently recognized as truly supranational is the European Union (EU). The EU successfully grew from a core of six countries in the 1950s to its present membership of 27 states. Figure 6.5 illustrates this expansion over the course of seven stages of accession. Despite recent economic problems in the EU, including threats to withdraw from the union itself, the EU is likely to continue to grow in the future, as many nonmember European states express interest in joining the union.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.4

What might this map indicate about globalization?

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.5

What reasons can you suggest for the accession of several Eastern European states to the EU in 2004 and 2007?

At its inception, the EU was merely a customs union designed to lower or remove tariffs hindering trade, but it gradually took on political and cultural roles as well. An underlying motivation to form the EU was to weaken the power of member countries so that they could never again wage war against one another—a response to the devastation of Europe in two world wars. Today, EU law dictates that member states elect representatives to a European Parliament that supersedes their national governments in a broad range of policy making. However, some member states retain a degree of authority and autonomy in choosing whether or not to comply with EU measures. Most of the EU uses a single monetary currency, the euro, and most international borders within the EU are open, requiring no passport checks.

In addition to establishing measures that ease international trade and travel, the EU has attempted to standardize a range of social norms related to the tolerance of religious and ethnic difference, human rights, and gender relations. However, due to the ability of some member states to choose noncompliance with these (and other) EU measures, they have not, as yet, been adopted universally throughout the union.

156

intergovernmental organization An international organization that does not require member states to relinquish sovereignty in order to benefit from cooperation between states in the association.

regional trading bloc Entity formed by an agreement made among geographically proximate countries to reduce trade barriers and to better compete with other regional markets.

North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA) An intergovernmental organization composed of Canada, Mexico, and the United States, designed to serve as a trading bloc.

Resembling supranational organizations, but different from them in key ways, are intergovernmental organizations. These organizations do not require member states to relinquish sovereignty in order to benefit from cooperation between states within the association, and they exhibit a lesser degree of cohesion than supranational organizations. Examples of intergovernmental organizations include the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Central American Integration System (SICA) (Table 6.1, below). Some intergovernmental organizations, like the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), aspire to become true supranational organizations one day and thus increasingly take on integrated functions. However, most remain simply cooperative associations with certain shared goals, like the Arab League and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Some intergovernmental organizations serve primarily as regional trading blocs, which are designed to reduce trade barriers among its members and to better compete with other regional markets. One such organization is the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA). This organization comprises Canada, Mexico, and the United States, and it promotes the freer flow of goods and services across member state borders. There has been talk of NAFTA expanding its role to become a union of North American states, but only time will tell if supranational status will ultimately be established within this organization.

Reflecting on Geography

Question 6.6

What will motivate the existing and prospective member countries of the European Union to continue to sacrifice aspects of their independence to create a stronger union?

Table 6.1:

Selected Intergovernmental Organizations in the Western Hemisphere

| Organization | Year Established | Member States | Key Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caribbean Community (CARICOM) | 1972 | Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago (Associate Members: Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands) |

|

| Central American Integration System (SICA) | 1993 | Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama (Associate Member: Dominican Republic) |

|

| North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)* | 1994 | Canada, Mexico, United States |

|

| Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) | 2004 | Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela |

|

*NAFTA has discussed incorporating greater integration measures in the future but currently is not equivalent in function or scope to the other international organizations shown in Table 6.1.

6.0.2 Electoral Geographical Regions

Electoral Geographical Regions

electoral geography The study of the interactions among space, place, and region and the conduct and results of elections.

Voting in elections creates another set of political regions. A free vote of the people on some controversial issue provides one of the purest expressions of culture, revealing attitudes on religion, ethnicity, and ideology. Geographers can devise formal culture regions based on voting patterns, giving rise to the subspecialty known as electoral geography.

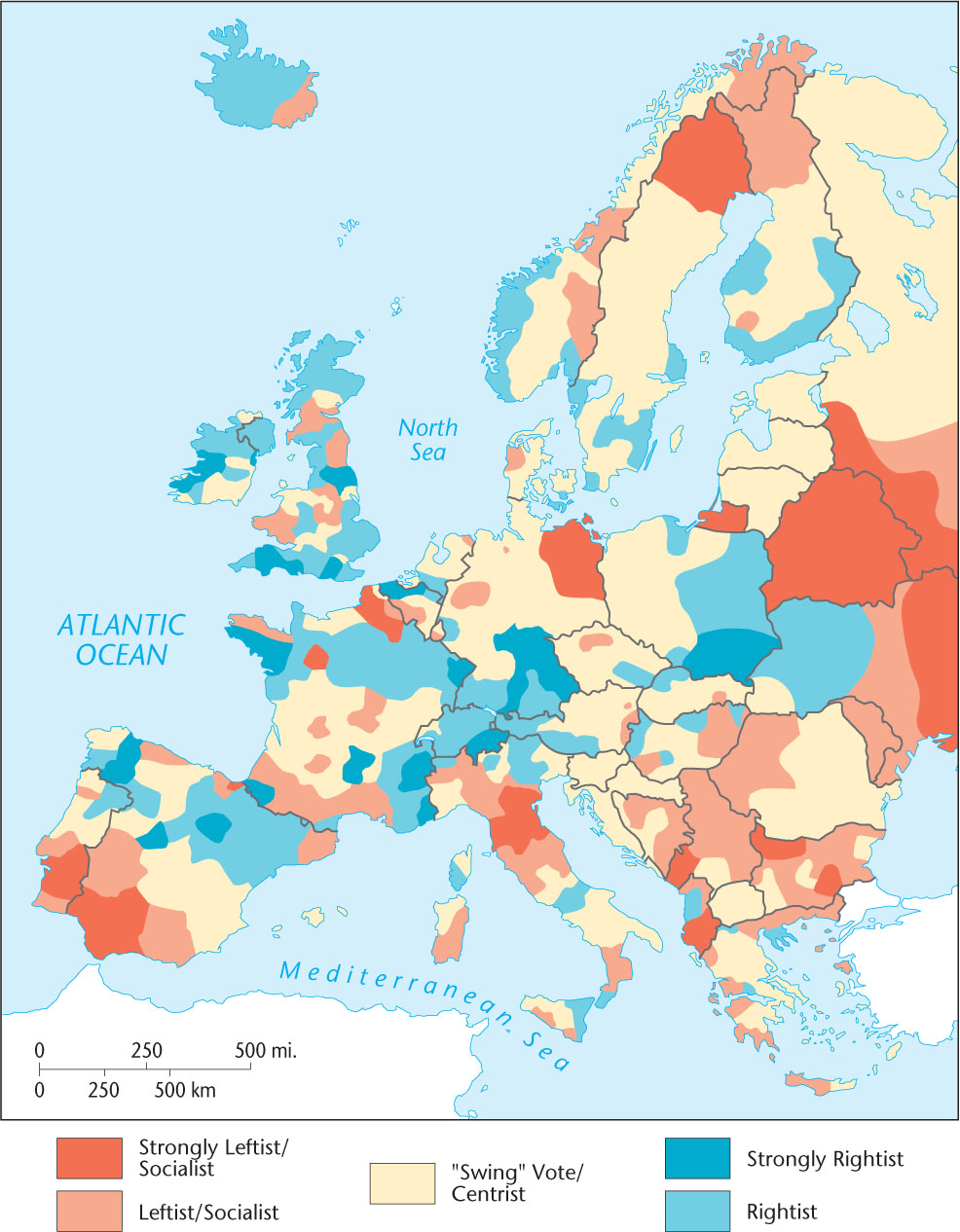

Mapping voting tendencies over many decades shows deep-rooted, formal electoral behavior regions. In Europe, for example, some districts and provinces have a long record of rightist sentiment, and many of these lie toward the center of Europe. Peripheral areas, especially in the east, are often leftist strongholds (Figure 6.6). Every country where free elections are permitted has a similarly varied electoral geography. In other words, cumulative voting patterns typically reveal sharp and pronounced regional contrasts. Electoral geographers refer to these borders as cleavages.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.7

How does the communist era continue to express itself?

Electoral geographers also concern themselves with functional regions, in this case the voting district or precinct. Their interests are both scholarly and practical. For example, following each census, political redistricting takes place in the United States. In redistricting, new boundaries are drawn for congressional districts to reflect the population changes since the previous census. The goal is to establish voting areas of more or less equal population and to increase or reduce the number of districts depending on the amount and direction of change in total population. These districts form the electoral basis for the U.S. House of Representatives. State legislatures are based on similar districts. Geographers often assist in the redistricting process.

gerrymandering The drawing of electoral district boundaries in an awkward pattern to enhance the voting impact of one constituency at the expense of another.

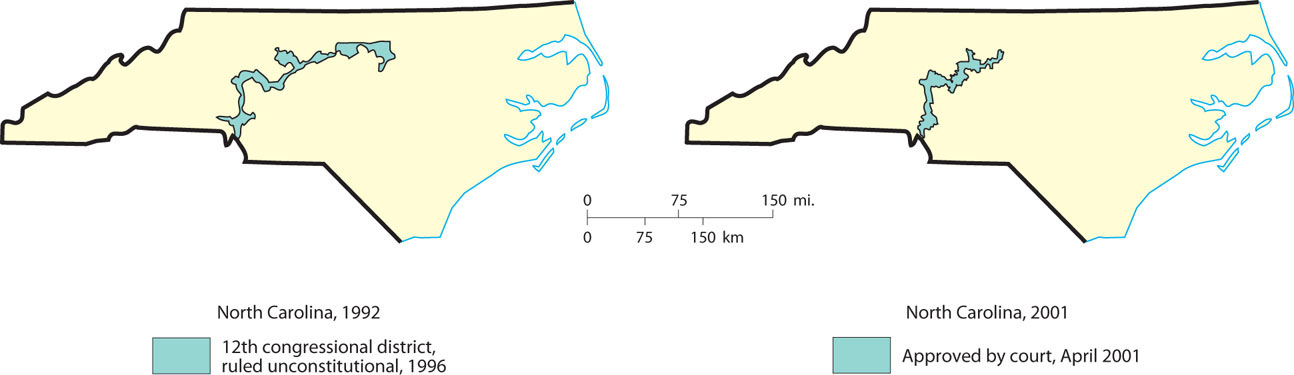

The pattern of voting precincts or districts can influence election results. If redistricting remains in the hands of legislators, then the majority political group or party will often try to arrange the voting districts geographically in such a way as to maximize and perpetuate its power. Cleavage lines will be crossed to create districts that have a majority of voters favoring the party in power or some politically important ethnic group. This practice is called gerrymandering (Figure 6.7), and the resultant voting districts often have awkward, elongated shapes. Gerrymandering can be accomplished by one of two methods. One is to draw district boundaries so as to concentrate all of the opposition party into one district, thereby creating an unnecessarily large majority while also ensuring that it cannot win elsewhere. A second is to draw the district boundaries so as to dilute the opposition’s vote so that it does not form a simple majority in any district.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.8

Besides ensuring a particular racial makeup of the winners, what other goals might be involved in gerrymandering?

159

6.0.3 Red States, Blue States, Purple States

Red States, Blue States, Purple States

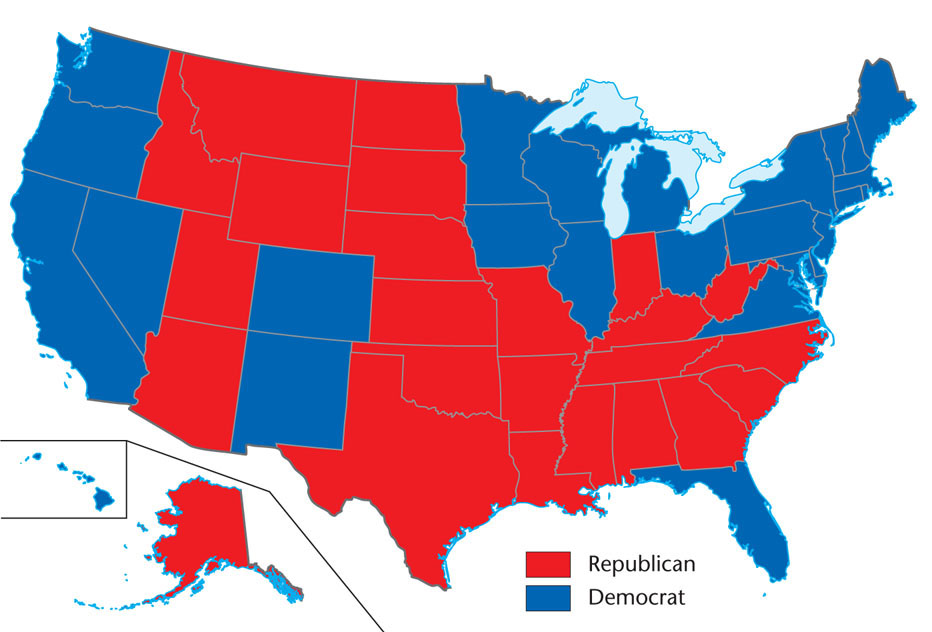

In recent years, various commentators in academia and the popular media have used maps of national election results to suggest that the United States is divided into distinct culture regions. We can trace this argument to the postelection analysis of the controversial 2000 presidential election, when for the first time news media adopted a universal color scheme for mapping voter preferences. States where the majority of voters favored the Democratic presidential candidate were assigned the color blue, whereas those favoring the Republican candidate were assigned red. When cartographers mapped the state-by-state results of the 2000 election, as well as subsequent presidential elections, the solid blocks of starkly contrasting colors gave the appearance of a deeply divided country. Figure 6.8 illustrates the “red state/blue state” pattern resulting from the 2012 presidential election.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.9

In 2012, which parts of the country were “red”? Which were “blue”?

160

The terms red state and blue state entered the popular lexicon in reference to the division of the United States into regions of “conservative” and “liberal” cultures that these maps implied. These maps, so common in the popular media, are overly simplistic and therefore misleading. For example, the solid red coloring of the states represented in Figure 6.8 implies that much of the United States is culturally and politically conservative. However, this map gives inordinate visual importance to states of larger areal extent, no matter their population, and exaggerates the appearance of sharp political and geographic divisions within the country. This exaggeration results from the U.S. electoral system, in which a state is designated as “red” or “blue” based on a simple majority in that state’s popular vote. In Figure 6.8 you can see that in the 2012 presidential election, Governor Mitt Romney took almost half the U.S. states (24 total) but received only 206 electoral votes. Incumbent President Barack Obama received 332 electoral votes and won the election.

161

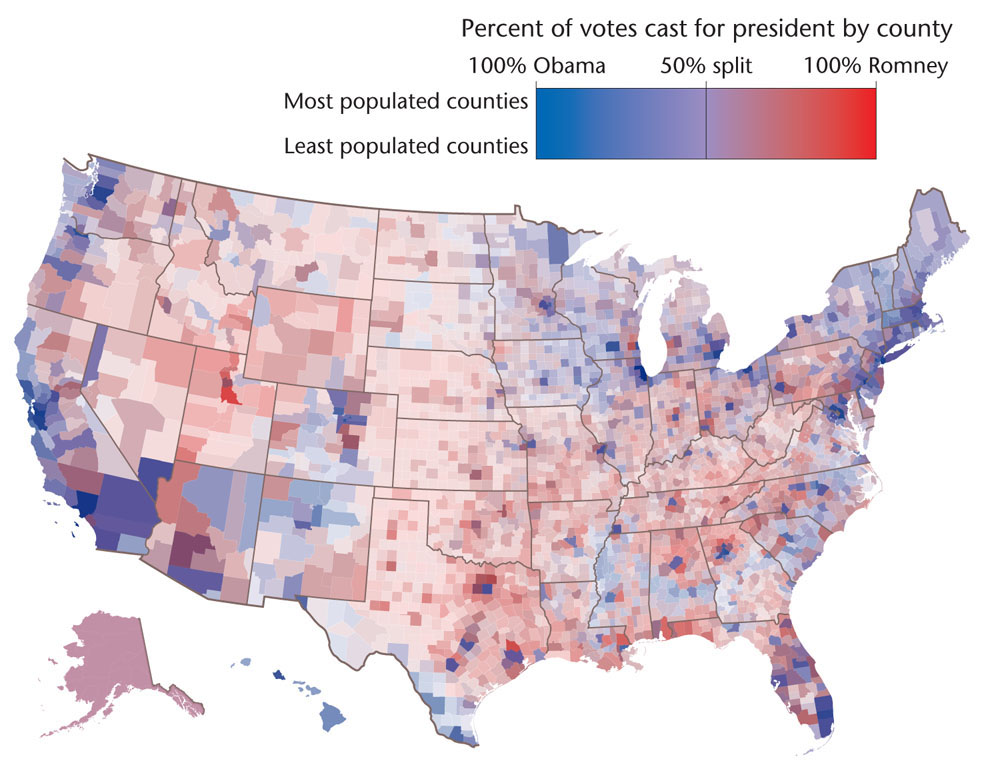

The limitations of the red state/blue state designation have led to the introduction of the term purple state to signify the mix of votes in a particular state. Virginia is one example of a purple state. Historically a Republican stronghold, Virginia has been carried (by a narrow margin) by the Democratic presidential candidate in the two most recent presidential elections. If we apply the purple state idea (that is, shadings of color rather than stark contrasts between just two colors) to county-level election results, we find that the simplistic division of the United States into liberal and conservative regions begins to break down. As Figure 6.9 shows, there is a great deal of county-by-county variation within states across the United States.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.10

How does the use of shading affect our understanding of a sharply divided American electorate that appears so prominent in Figure 6.8? What other kinds of geographic voting patterns emerge?