Political Landscapes

Political Landscapes

How does politics influence landscape? How are landscapes politicized? The world over, national politics is literally written on the landscape. State-driven initiatives for frontier settlement, economic development, and territorial control have profound effects on the landscape. Conversely, political writers and politicians look to landscape as a source of imagery to support or discredit political ideologies.

6.0.15 Imprint of the Legal Code

Imprint of the Legal Code

Many laws affect the cultural landscape. Among the most noticeable are those that regulate the land-survey system because they often require that land be divided into specific geometric patterns. As a result, political boundaries can become highly visible (Figure 6.20). In Canada, the laws of the French-speaking province of Québec encourage land survey in long, narrow parcels, but most English-speaking provinces, such as Ontario, use a rectangular system. Thus, the political border between Québec and Ontario can be spotted easily from the air.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.23

Why does the cultural landscape so vividly reveal the political border?

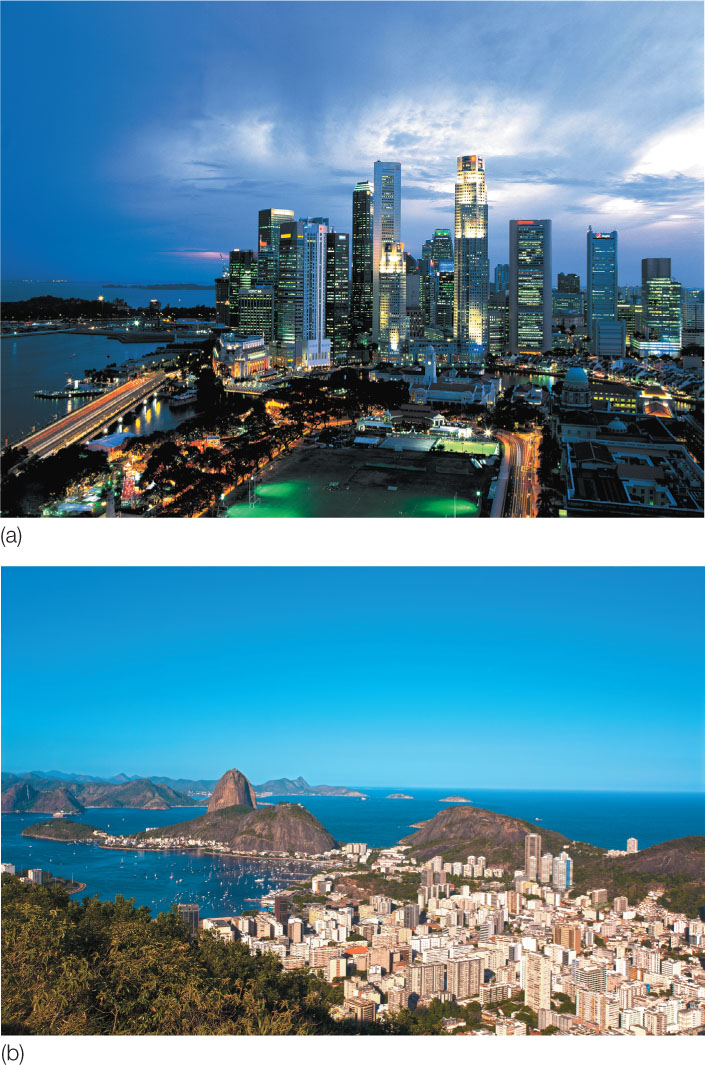

Legal imprints can also be seen in the cultural landscape of urban areas. In Rio de Janeiro, height restrictions on buildings have been enforced for a long time. The result is a waterfront lined with buildings of uniform height (Figure 6.21). By contrast, most American cities have no height restrictions, allowing skyscrapers to dominate the central city. The consequence is a jagged skyline for cities such as San Francisco or New York City. Many other cities around the world lack height restrictions, such as Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur, which has the world’s tallest skyscrapers.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.24

Does your city have restrictions on building heights or architectural details? Explain.

173

Perhaps the best example of how political philosophy and the legal code are written on the landscape is the so-called township and range system of the United States. The system is the brainchild of Thomas Jefferson—an early U.S. president and one of the authors of the U.S. Constitution—who chaired a national committee on land surveying that resulted in the U.S. Land Ordinance of 1785. Jefferson’s ideas for surveying, distributing, and settling the western frontier lands as they were cleared of Native Americans were based on a political philosophy of agrarian democracy. Jefferson believed that political democracy had to be founded on economic democracy, which in turn required a national pattern of equitable land ownership by small-scale independent farmers. In order to achieve this agrarian democracy, the western lands would have to be surveyed into parcels that could then be sold at prices within reach of family farmers of modest means.

Jefferson’s solution was the township and range system, which established a grid of square townships with 6-mile (9.6-kilometer) sides across the Midwest and West. Each of these was then divided into 36 sections of 1 square mile (2.6 square kilometers), which were in turn divided into quarter-sections, and so on. Sections were to be the basic landholding unit for a class of independent farmers. Townships were to provide the structure for self-governing communities responsible for public schools, policing, and tax collection. With the exception of the 13 original colonies and a few other states or portions of states, a gridlike landscape was imposed on the entire country as a result of Jefferson’s political philosophy and accompanying land-survey system (Figure 6.22).

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.25

Why did the United States government deem it necessary to impose a regular grid pattern on the land?

6.0.16 Physical Properties of Boundaries

Physical Properties of Boundaries

Demarcated political boundaries can also be strikingly visible, forming border landscapes. Political borders are usually most visible where restrictions limit the movement of people between neighboring countries. Sometimes such boundaries are even lined with cleared strips, barriers, pillboxes, tank traps, and other obvious defensive installations. At the opposite end of the spectrum are international borders, such as that between Tanzania and Kenya in East Africa, that are unfortified, thinly policed, and in many places very nearly invisible. Even so, undefended borders of this type are usually marked by regularly spaced boundary pillars or cairns, customhouses, and guardhouses at crossing points (Figure 6.23).

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.26

Why would Sweden and Norway do this?

174

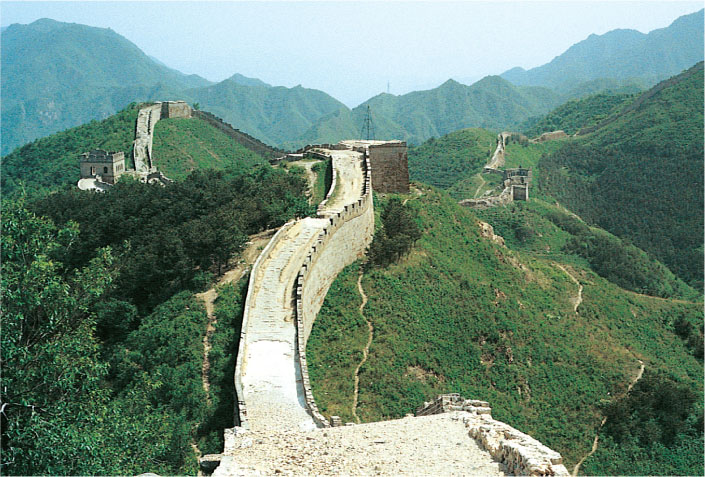

The visible aspect of international borders is surprisingly durable, sometimes persisting centuries or even millennia after the boundary becomes obsolete. Ruins of boundary defenses, some dating from ancient times, are common in certain areas. The Great Wall of China is probably the best-known reminder of past boundaries (Figure 6.24). Hadrian’s Wall in England, which marks the northern border during one stage of Roman occupation and parallels the modern border between England and Scotland, is a similar reminder.

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.27

Can you think of comparable modern structures?

6.0.17 The Impress of Central Authority

The Impress of Central Authority

Attempts to impose centralized government appear in many facets of the landscape. Railroad and highway patterns focused on the national core area, and radiating outward like the spokes of a wheel to reach the hinterlands of the country, provide good indicators of central authority. In Germany, the rail network developed largely before unification of the country in 1871. As a result, no focal point stands out. However, the superhighway system of auto-bahns, encouraged by Hitler as a symbol of national unity and power, tied the various parts of the Reich to such focal points as Berlin or the Ruhr industrial district.

The visibility of provincial borders within a country also reflects the central government’s strength and stability. Stable, secure countries, such as the United States, often permit considerable display of provincial borders. Displays aside, such borders are easily crossed. Most state boundaries within the United States are marked with signboards or other features announcing the crossing. By contrast, unstable countries, where separatism threatens national unity, often suppress such visible signs of provincial borders. Also in contrast, such “invisible” borders may be exceedingly difficult to cross when a separatist effort involves armed conflict.

Reflecting on Geography

Question 6.28

What visible imprints of the Washington, D.C.–based central government can be seen in the political landscape of the United States?

6.0.18 National Iconography on the Landscape

National Iconography on the Landscape

The cultural landscape is rich in symbolism and visual metaphor, and political messages are often conveyed through such means. Statues of national heroes or heroines and of symbolic figures such as the goddess Liberty or Mother Russia form important parts of the political landscape, as do assorted monuments. The elaborate use of national colors can be visually powerful as well. Figure 6.25 illustrates this form of national iconography in the Netherlands during a Queen’s Day celebration, on which many citizens dress in orange, the Dutch national color. Landscape symbols such as the Rising Sun flag of Japan, the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor, and the Latvian independence pillar in Riga (which stood untouched throughout half a century of Russian-Soviet rule) evoke deep patriotic emotions. The sites of heroic (if often futile) resistance against invaders, as at Masada in Israel, prompt similar feelings of nationalism. A memorial to the victims of the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, China, provides another example of this type of iconographic imprint of the cultural landscape (Figure 6.26).

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.29

Why do you think that citizens of many countries choose to partake in nationalistic celebrations that make a visible imprint on the cultural landscape?

Thinking Geographically

Question 6.30

Can you think of some examples of iconographic memorials on the U.S. landscape that mark national tragedies?

175

Some geographers theorize that the political iconography of landscape derives from an elite, dominant group in a country’s population and that its purpose is to legitimize or justify its power and control over an area. The dominant group seeks both to rally emotional support and to arouse fear in potential or real enemies. As a result, the iconographic political landscape is often controversial or contested, representing only one side of an issue. Consider Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota, which features the carved heads of four U.S. presidents. The Black Hills are sacred to the Native Americans who controlled the land before whites seized it. How might these Native Americans, the Lakota Sioux, perceive this monument? Are any other political biases contained in it? Cultural landscapes are always complicated and subject to differing interpretations and meanings, and political landscapes are no exception.