Cultural Interaction in Religion

Cultural Interaction in Religion

How does religion influence other aspects of culture? Can nonreligious elements within a culture help shape a faith? Just as the interaction between religious belief and the environment can shape both religions and the land, religious faith is similarly intertwined with other aspects of culture.

Religion and Economy

Religion and Economy

In the economic sphere, religion can guide commerce, determine which crops and livestock are raised by farmers and what foods and beverages people consume, and even help decide a person’s type of employment and the neighborhood in which he or she resides. Every known religion expresses itself in food choices to one degree or another. In some faiths, certain plants and livestock, as well as the products derived from them, are in great demand because of their roles in religious ceremonies and traditions. When this is the case, the plants or animals tend to spread or relocate with the faith.

For example, in some Christian denominations in Europe and the United States, celebrants drink from a cup of wine that they believe is the blood of Christ during the sacrament of Holy Communion. The demand for wine created by this ritual aided the diffusion of grape growing from the sunny lands of the Mediterranean to newly Christianized districts beyond the Alps in late Roman and early medieval times. The vineyards of the German Rhine were the creation of monks who arrived from the south between the sixth and ninth centuries. For the same reason, Catholic missionaries introduced the cultivated grape to California in an example of relocation diffusion. In fact, wine was associated with religious worship even before Christianity arose. Vineyard keeping and winemaking spread westward across the Mediterranean lands in ancient times in association with worship of the god Dionysus.

Religion can often explain the absence of individual crops or domestic animals in an area and can also explain regional variations in agricultural practices. For example, taboos associated with the consumption of pork in religions such as Islam, Judaism, and Seventh-Day Adventism correspond closely to certain regions’ lack of pork production. Another example of the influence of religious beliefs on agricultural practices can be found when comparing India, a predominantly Hindu state, with other regions that are not as heavily influenced by Hinduism.

179

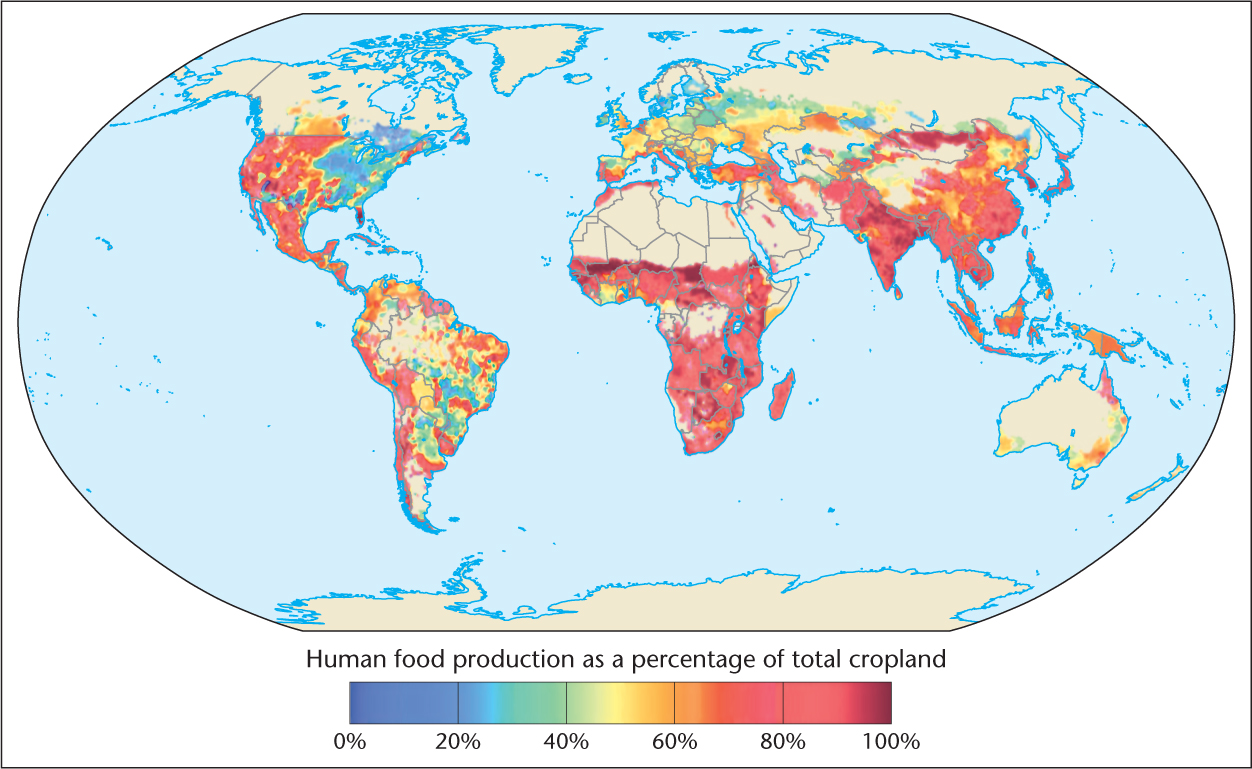

The Hindu practice of avoiding beef consumption produces a recognizable pattern on the economic landscape. Figure 7.19 illustrates that large swaths of North America, South America, and Europe produce grain crops primarily for the feeding of livestock such as cows and pigs. Though inefficient from an energy standpoint, this use of grain supports the production of highly desired meat for human consumption in these regions. In India, however, a strikingly different agricultural practice is evident on the landscape. Due in large part to the Hindu prohibition against the consumption of beef, most grain crops produced within the country go directly toward feeding the massive human population, rather than feeding a cattle population destined for human consumption. In many other developing regions of the world with rapidly increasing populations, crops are similarly directed toward human consumption.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.20

How might the pattern shown on the map change in a developing region that becomes more economically stable and affluent over time?

The case of India’s sacred cows provides an intriguing example of how religious beliefs shape the role of animals in society, in this instance avoiding the use of cows as food while emphasizing the animal’s sacred as well as its practical functions. Although only one in three of India’s Hindus practices vegetarianism, almost none of India’s Hindu population will eat beef, and many will not use leather. Why, in a populous country such as India, where many people are poor and where food shortages have plagued regions of the country in previous decades, do people refuse to consume beef? There are several quite legitimate reasons. First, the dairy products provided by cow’s milk and its by-products, such as yogurt and ghee (clarified butter), are central to many regional Indian cuisines. If the cow is slaughtered, it will no longer be able to provide milk. Second, in areas of the world that rely heavily on local agriculture for food production, such as India, cows provide valuable agricultural labor in tilling fields. Cows also provide fertilizer in the form of dung. Finally, the value of the cow has been incorporated into Indian Hindu beliefs and practices over many centuries and has become a part of culture. Krishna, an incarnation of the major Hindu deity Vishnu, is said to be both the herder and the protector of cows. Nandi, who is the deity Shiva’s attendant, is represented as a bull.

179

Religious Pilgrimage

Religious Pilgrimage

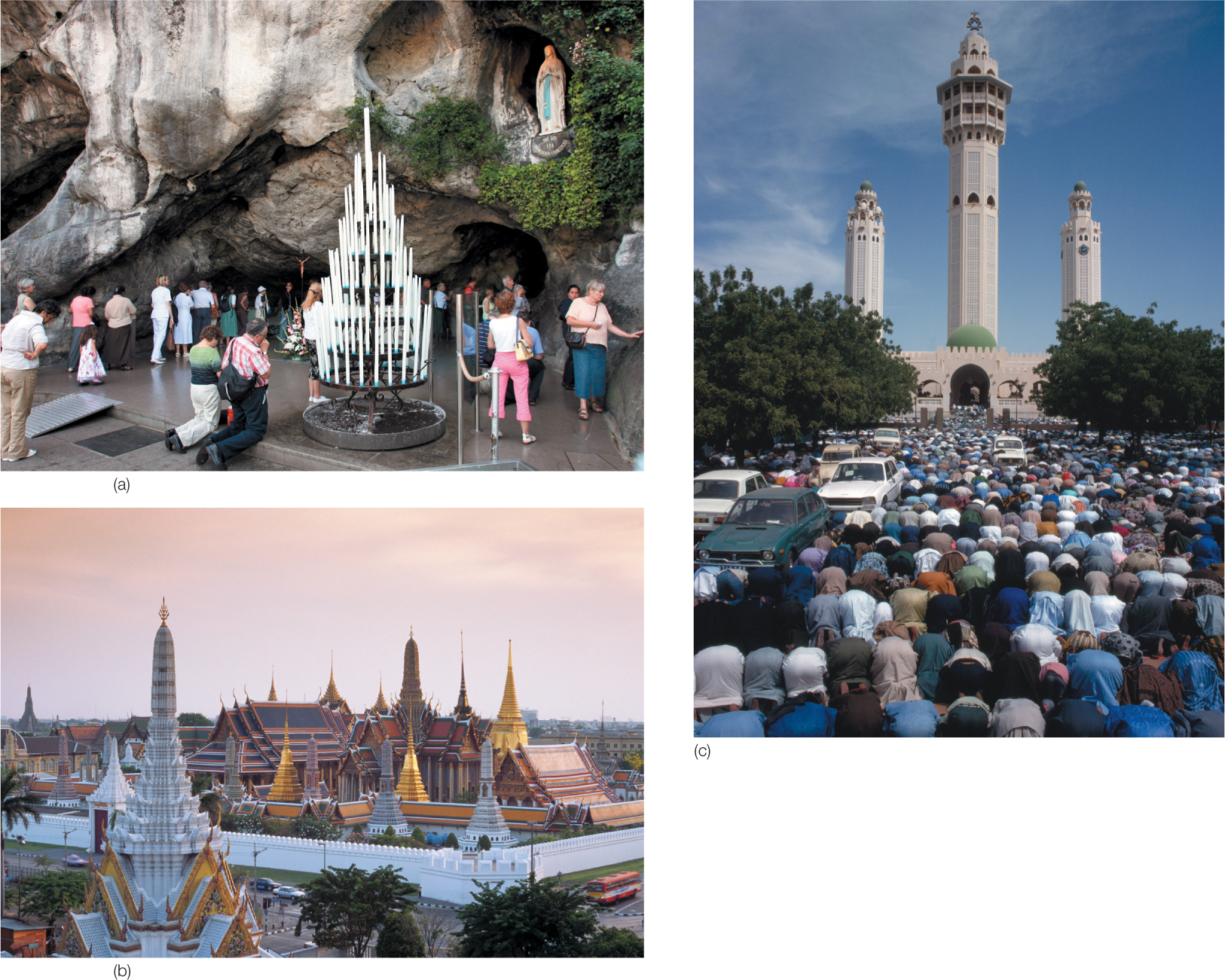

pilgrimage A journey to a place of religious importance.

For many religious groups, journeys to sacred places, or pilgrimages, are an important aspect of their faith (Figure 7.20). Pilgrimages are typical of both ethnic and proselytic religions. They are particularly significant for followers of Islam, Hinduism, Shinto, and Roman Catholicism. Along with missionaries, pilgrims constitute one of the largest groups of people voluntarily on the move for religious reasons. Pilgrims do not aim to convert people to their faith through their journeys. Rather, they enact in their travels a connection with the sacred spaces of their faith. Indeed, some religions mandate pilgrimage.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.21

What other kinds of places could be considered pilgrimage destinations?

The sacred places visited by pilgrims vary in character. Some have been the setting for miracles; a few are the regions where religions originated or areas where the founders of the faith lived and worked; others contain sacred physical features such as rivers, caves, springs, and mountain peaks; and still others are believed to house gods or are religious administrative centers where leaders of the religion reside. Examples include the Arabian cities of Mecca and Medina in Islam, which are cities where Muhammad was born and resided and thus form Islam’s culture hearth; Rome, the home of the Roman Catholic Pope; the French town of Lourdes, where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to a girl in 1858; the Indian city of temples on the holy Ganges River, Varanasi, which is a destination for Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain pilgrims; and Ise, a shrine complex located in the culture hearth of Shinto in Japan. Places of pilgrimage might be regarded as places of spatial convergence, or nodes, of functional culture regions.

179

In some localities, the pilgrim trade provides the only significant source of revenue for the community. Lourdes, a town of about 16,000, attracts 4 million to 5 million pilgrims each year, many seeking miraculous cures at the famous grotto where the Virgin Mary reportedly appeared. Not surprisingly, among French cities, Lourdes ranks second only to Paris in number of hotels, although most of these are small. Mecca, a small city, annually attracts millions of Muslim pilgrims from every corner of the Islamic culture region as they perform the hajj, or fifth pillar of Islam, which every able-bodied Muslim who can afford to do so should do at least once in his or her lifetime. By land, by sea, and (mainly) by air, the faithful come to this hearth of Islam, a city closed to all non-Muslims (Figure 7.21). Such mass pilgrimages obviously have a major impact on the development of transportation routes and carriers, as well as other provisions such as inns, food, water, and sanitation facilities.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.22

What other examples can you cite of places that are restricted to members of a particular religion?

Religion and Political Geography

Religion and Political Geography

sharia A legal framework, derived from the religious interpretation of Islamic texts, that governs almost all aspects of public life and some aspects of private life for Muslims living under this system of jurisprudence.

Cultural, economic, social, and political arenas often work together in societies around the world. An example of this interaction can be found in the Muslim practice of sharia. Sharia means “the way” or “the path to the water source” in Arabic, and it constitutes a religion-based method of lawmaking that guides many aspects of Muslim life, including marriage and divorce, family obligation, religious obligation, financial agreements, and criminal justice. Sharia developed from precedents and analogies found in the Qur’an and in teachings of the Prophet Mohammed, though sharia rulings are sometimes grounded in Muslim community consensus.

Due to different schools of thought within Islam, sharia practices vary widely from state to state throughout the Muslim world. Some contemporary Muslim states, including Saudi Arabia and Iran, follow a very traditional form of sharia and therefore do not have democratic constitutions or legislatures. In these states, secular rulers have limited authority to make or change laws because they are based on sharia as interpreted by religious scholars. In contrast to these traditional states, many majority-Muslim countries (including Tanzania, Indonesia, and Lebanon) have a dual system wherein the government is secular, but Muslim citizens can opt to bring family and financial disputes to special sharia courts. Other Muslim-majority states, including Azerbaijan, Chad, and Senegal, have declared their governments to be purely secular. However, in these countries, sharia may still influence some local customs. The Arab Spring of 2011 (see chapter 6, page 164) in Libya, Tunisia, and Egypt led to the ousting of “pro-Western” autocratic governments in favor of governments led by Islamic political parties. As a result, support for certain traditional sharia practices has been renewed in these states.

Another example demonstrating how contemporary religion and politics work together can be found in Latin America and the Caribbean. In this region, Roman Catholicism has dominated the religious landscape since the time of the Iberian conquerors in the late 1400s. More Catholics live in this region than in any other on Earth, with three out of every five Catholics residing here. Brazil is the largest Catholic country in the world in terms of population. However, the Catholic Church has been on the decline in Brazil and throughout the region in recent decades. Fewer than 80 percent of Brazilians are Catholics today, whereas 50 years ago that figure was more than 95 percent. What has happened to the region’s Catholics?

Briefly, more and more Latin Americans seem to believe that the Catholic Church has failed to keep in touch with the needs and concerns of contemporary urban societies. Birth control, divorce, and persistent poverty are issues that have not been addressed by Roman Catholicism to the satisfaction of many Latin Americans. As a result, more and more are turning toward evangelical Protestant faiths, such as the Seventh-Day Adventist and Pentecostal churches (Figure 7.22). The focus of these churches on thrift, sobriety, and resolving problems directly rather than through the mediation of priests is appealing to many. Others find their needs are best addressed by an array of African-based spiritist religions, which include Umbanda, Candomblé, and Santería.

179

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.23

What kind of diffusion seems to be operating here?

Religion on the Internet

Religion on the Internet

In the mid-fifteenth century, Gutenberg’s printing press made the Bible available to a mass audience. The Internet, proponents argue, represents a similar technological revolution, one that will inevitably attract new adherents to religious faiths. Gathering together regularly in a holy place—a mosque, temple, church, or shrine—is at the heart of most organized religions. Traditionally, people have come together to receive sacraments, sing, pray, and celebrate major life events in houses of worship. With the tens of thousands of religious web sites now in existence, it is no longer necessary to physically go to a place of worship. Rather, you can sit in front of a computer, at any time of the day or night, and read a holy book, submit and read online prayers, engage in theological debate, or watch broadcasts of religious services.

For cultural geographers, the most interesting dimension of online worship concerns what it does to the role of place in a global society. Clearly, the Internet has made it possible to practice religion in a way that is not linked to a specific place of worship, but is this a good thing? Supporters of practicing religion online contend that it is a good thing, because people can become members of virtual communities that would not otherwise have been available to them in times of spiritual need. Now illness, invalidism, or the pressures of a busy life need not present a barrier to worship. Detractors argue that solitary worship online erodes the place-based communities that are at the heart of many religions. As people pick and choose elements from the different faiths available online, will religions converge into a watered-down, homogeneous “McFaith”?

Reflecting on Geography

Question 7.24

Are virtual religious communities created through the Internet an acceptable substitute for traditional place-based religious communities?

Religion’s Relevance in a Global World

Religion’s Relevance in a Global World

In the United States, geographer Roger Stump points to a twentieth-century trend toward fragmentation and dominance of particular religions in regions of the United States. Baptists in the South, Lutherans in the upper Midwest, Catholics in the Northeast and Southwest, and Mormons in the West each dominate their respective regions more thoroughly today than at the turn of the twentieth century. Each of the four traditions is socially conservative and has a strong, long-standing infrastructure. Other experts, however, believe that American culture is becoming more religiously mixed, with weakening regional borders around religious core areas.

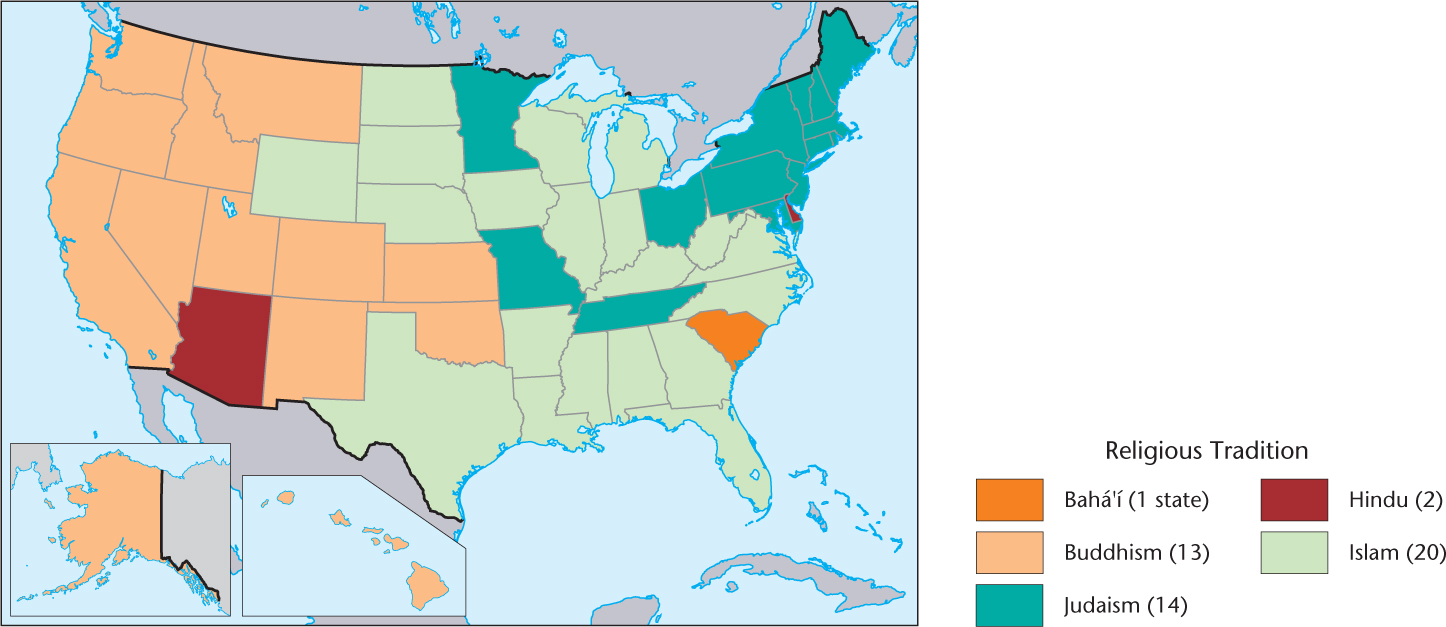

Newer religious influences, too, are making an entrance onto the American religious stage. More recently arrived religions to the United States tend to be regionally clustered as a result of their strong association with particular migrant groups (Figure 7.23). In other words, as various migrant populations arrived and settled in particular regions of the country during recent decades, they carried their religious traditions with them. Along with Christianity, these growing religions exert influence on many aspects of American culture. For example, if you have ever practiced yoga or meditation, you are engaging in Hindu and Buddhist practices. Many Americans do yoga or meditate as a means of physical or spiritual growth, for stress relief, or even to keep up with the latest trends, rather than as part of a religious practice. Yet they are among the growing number of Americans who have found a blend of Eastern and Western religious practices to be compatible with their beliefs and lifestyles.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.25

How might you explain the predominance of Buddhism in the western United States?

secular Characterized by little or no religious belief or practice.

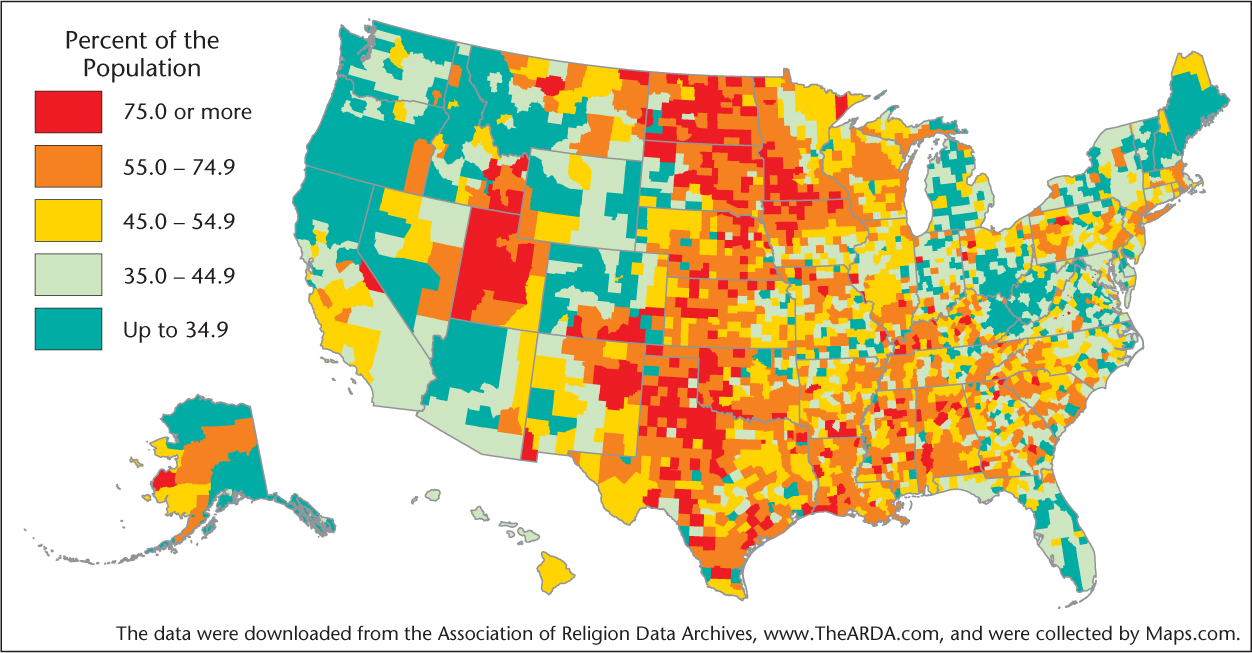

Despite the influence of an increasing number of religions and blends of religions on the U.S. cultural landscape, overall, religious adherence has been on the decline in the United States in recent decades. The American Religious Identification Survey, compiled in 2008, found 46 million nonreligious adults in the United States, or about 20.2 percent of the population. In the state of Vermont, for example, approximately 40 percent of adults are not affiliated with a church. As a result of these shifts in American religious adherence, areas of religious vitality now often lie alongside secular areas (that is, areas with little or no religious belief or practice) in a disorderly jumble. Figure 7.24 illustrates this increasingly diverse cultural pattern on the American landscape.

179

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.26

What reason can you give for the higher rate of religious adherence in the highly urbanized areas of southern and central California as compared to much of the rest of the American West?

179

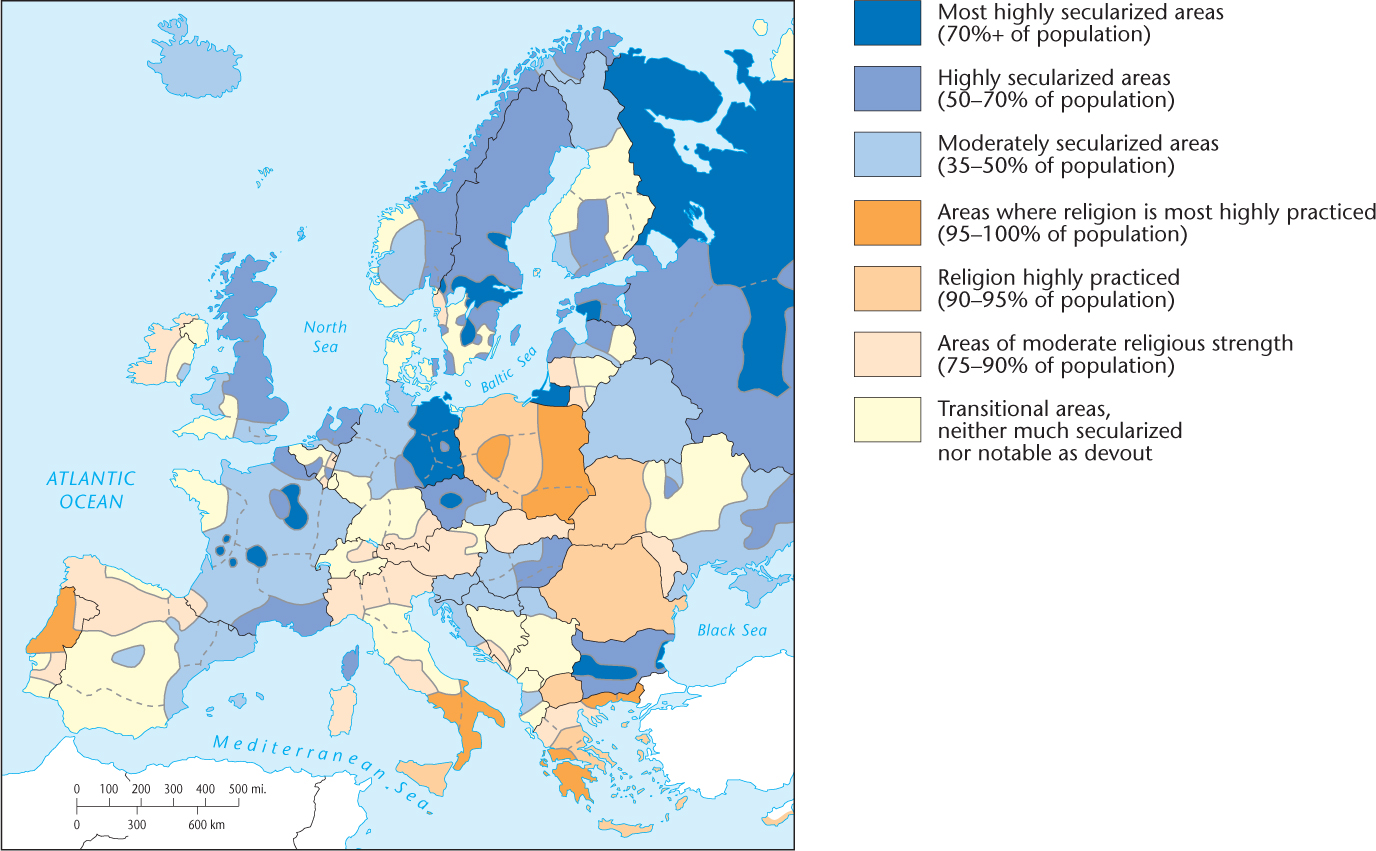

Outside of the United States, other regions have also experienced a trend toward secularization, particularly much of Europe (Figure 7.25). Globally, however, there has been a notable overall trend toward increasing religious adherence. This shift is largely attributable to population increases in the Middle East and parts of Africa, where most people strongly adhere to religious traditions such as Islam and Christianity. As a result of this global trend toward increasing religious adherence, the number of secular persons in the world decreased from 913 million in 2000 to approximately 640 million in 2010. However, there have been some national and regional instances of retreat from organized religion resulting from governments’ active hostility toward a particular faith or toward religion in general. For example, the French government has long discouraged public displays of religious faith. France’s long-standing secularism is evident in Figure 7.25. This secularization extends not only to France’s traditional Roman Catholicism, but to Jews and the rising Muslim population as well. In 2004, French law banned the wearing of skullcaps, headscarves, or large crosses in public schools. Such patterns once again reveal the inherent spatial variety of humankind and invite analysis by the cultural geographer.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.27

What causal forces might be at work here?