Religious Landscapes

Religious Landscapes

In what forms does religion appear in the cultural landscape? How does the visibility of religion differ from one faith or denomination to another? Religion is a vital aspect of culture; its visible presence can be striking, reflecting the role religious motives play in the human transformation of the landscape. In some regions, the religious aspect is the dominant visible evidence of culture, producing sacred landscapes. At the opposite extreme are areas almost purely secular in appearance. Religions differ greatly in visibility, but even those least apparent to the eye usually leave some subtle mark on the countryside.

Religious Structures

Religious Structures

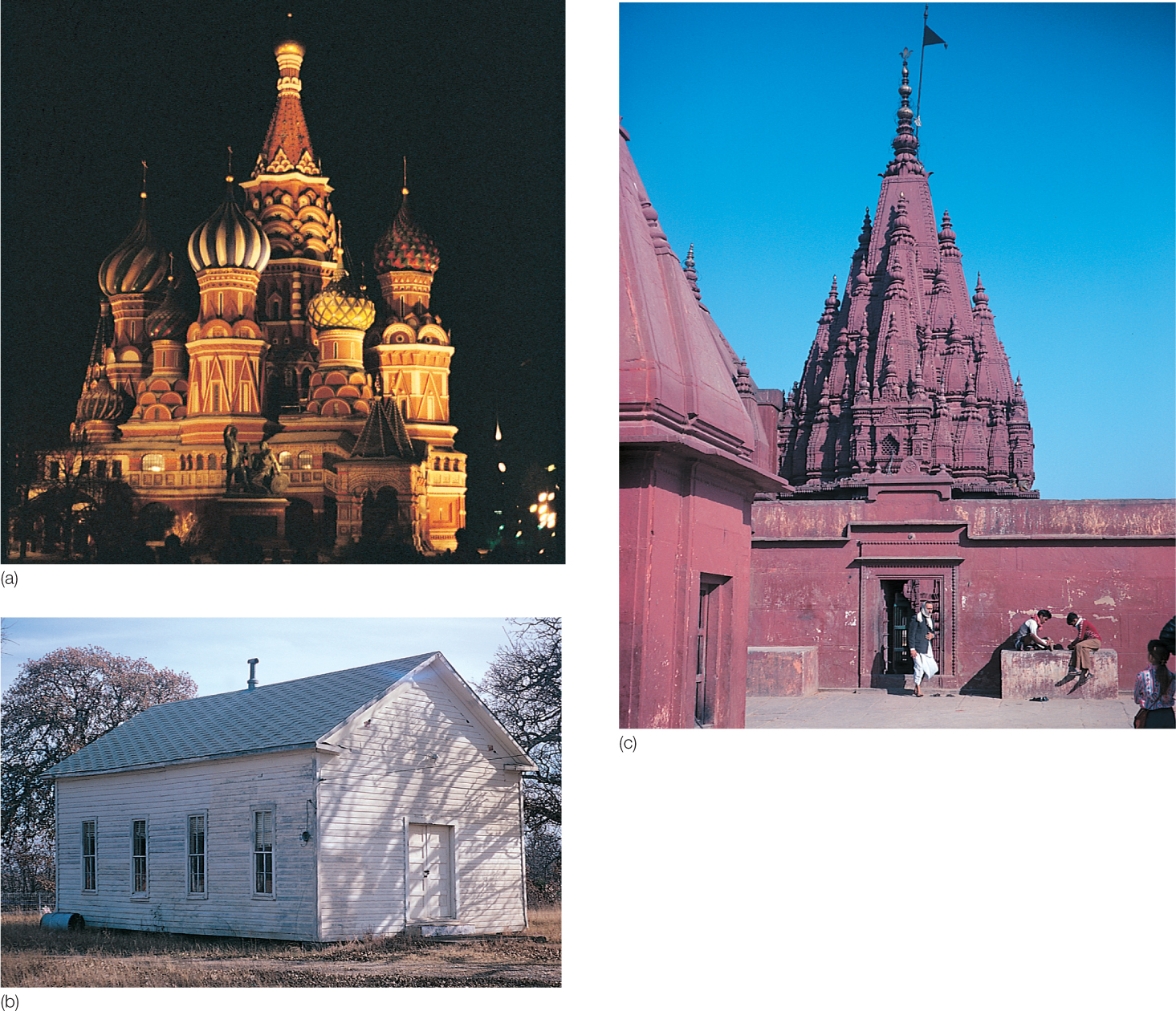

The most obvious religious contributions to the landscape are the buildings erected to house divinities or to shelter worshippers. These structures vary greatly in size, function, architectural style, construction material, and degree of ornateness (Figure 7.26). To Roman Catholics, for example, the church building is literally the house of God, and the altar is the focus of key rituals. Partly for these reasons, Catholic churches are typically large, elaborately decorated, and visually imposing. In many towns and villages, the Catholic house of worship is the focal point of the settlement, exceeding all other structures in size and grandeur. In medieval European towns, Christian cathedrals were the tallest buildings, representing the supremacy of religion over all other aspects of life.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.28

What beliefs are these icons expressing?

179

For many Protestants—particularly the traditional Calvinistic chapel-goers of British background, including Presbyterians and Baptists—the church building is, by contrast, simply a place to assemble for worship. The result is an unsanctified, small, simple structure that appeals less to the senses and more to personal faith. For this reason, traditional Protestant houses of worship typically are not designed for comfort, beauty, or high visibility but instead appear deliberately humble (see Figure Figure 7.26b). Similarly, the religious landscape of the Amish and Mennonites in rural North America, the “plain folk,” is very subdued because they reject ostentation in any form. Some of their adherents meet in houses or barns, and the churches that do exist are very modest in appearance, much like those of the southern Calvinists.

Islamic mosques are usually the most imposing items in the landscape, whereas the visibility of Jewish synagogues varies greatly. Hinduism has produced large numbers of visually striking temples for its multiplicity of gods, but much worship is practiced in private households with their own personal shrines (Figure 7.27).

179

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.29

What parallels to these shrines can be found in your community?

Nature religions such as animism generally place only a subtle mark on the landscape. Nature itself is sacred, and imposing features already present in the landscape—mountains, waterfalls, and grottos, for example—mean that few human-made shrines are needed. There are, not surprisingly, exceptions. In Korea, for example, where animism merged with Buddhism and the Chinese composite religion, animistic shrines survive in the landscape (Figure 7.28).

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.30

What do you speculate these stones might mean? What do they remind you of?

Houses of worship can also reveal subtler content and messages. In Polynesian Maori communities of New Zealand, for example, the marae, a structure linked to the pagan gods of the past, generally stands alongside the Christian chapel, which reflects the Maoris’ conversion (Figure 7.29). The landscape thus reflects the blending of two faiths.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.31

What does this juxtaposition tell us about the faith of the modern Maori?

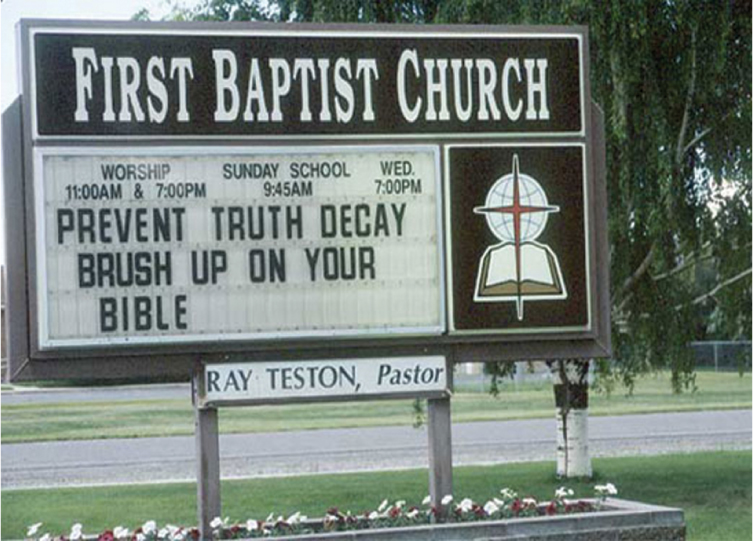

Paralleling this contrast in church styles are attitudes toward roadside shrines and similar manifestations of faith. Catholic culture regions typically abound with shrines, crucifixes, and other visual reminders of religion, as do some Eastern Orthodox Christian areas. Protestant areas, by contrast, are bare of such symbolism. Their landscapes, instead, display such features as signboards advising the traveler to “Get Right with God,” a common sight in the southern United States (Figure 7.30).

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.32

Why do American churches see the need to market themselves?

179

Faithful Details

Faithful Details

Not only buildings but also other architectural choices, such as color and landscaping elements, can convey spiritual meaning through the landscape. Consider the color green. The image of a Muslim mosque in northern Nigeria in Figure 7.31 depicts how green—sacred in Islam—appears often on mosque domes and minarets, the tall circular towers from which Muslims are called to prayer. The prophet Muhammad declared his favorite color to be green, and his cloak and turban were green. In Christianity, green also has positive connotations, symbolizing fertility, freedom, hope, and renewal. It is used in decorations, such as banners, and for clergy vestments, especially those associated with the Trinity and Epiphany seasons.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.33

Besides being Muhammad’s favorite color, why might green be a sacred color to Muslims?

Water, often used as a decorative element in fountains, baths, and pools, has religious meaning. In fact, all three of the great desert monotheisms—Islam, Christianity, and Judaism—consider water to have a special status in religious rituals. In general, followers of all three religions believe water has the ability to purify and cleanse the body as well as to purify and cleanse the soul of sins. Muslims use water in ablutions, or washing, of the hands, face, or ears before daily prayers and other rituals. Footbaths, or ablution fountains, are important features located outside mosques, and decorating with water, particularly pools and fountains, is a common practice in Islamic architecture. Central to Christianity is baptism, during which the new-born infant or adult convert is sprinkled with or fully immersed in holy water, symbolizing the cleansing of original sin for infants and repentance or cleansing from sin for adults. Jews may engage in a ritual bath, known as a mikveh, before important events, such as weddings (for women), or on Fridays, the evening of the Jewish Sabbath (for men). The story of the Great Flood, found in the Book of Genesis in the Old Testament (common to both Jews and Christians), depicts the washing away of the sins of the world so that it could be born anew.

179

Landscapes of the Dead

Landscapes of the Dead

Religions differ greatly in the type of tribute each awards to its dead. These variations appear in the cultural landscape. The few remaining Zoroastrians, called Parsees, who preserve a once-widespread Middle Eastern faith now confined to parts of India, have traditionally left their dead exposed to be devoured by vultures. Thus, the Parsee dead leave no permanent mark on the landscape. Hindus cremate their dead. Having no cemeteries, their dead, as with the Parsees, leave no obvious mark on the land. Yet on the island of Bali in Indonesia, Hinduism has blended with animism in such a way that temples to family ancestors occupy prominent places outside the houses of the Balinese, a landscape feature that does not exist in India itself (see Figure 7.27).

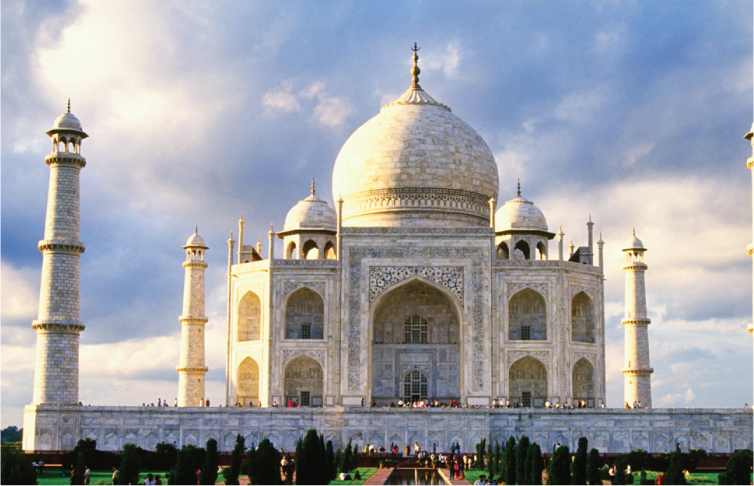

In Egypt, spectacular pyramids and other tombs were built to house dead leaders. These monuments, as well as the modern graves and tombs of the rural Islamic folk of Egypt, lie on desert land not suitable for farming (Figure 7.32). Muslim cemeteries are usually modest in appearance, but spectacular tombs are sometimes erected for aristocratic persons, giving us such sacred structures as the Taj Mahal in India (Figure 7.33), one of the architectural wonders of the world.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.34

Why is this a good place to build a cemetery?

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.35

Compare this structure with the mosque in Figure 7.31. How is it similar? How is it different?

Taoic Chinese typically bury their dead, setting aside land for that purpose and erecting monuments to their deceased kin. In parts of pre-Communist China, cemeteries and ancestral shrines take up as much as 10 percent of the land in some districts, greatly reducing the acreage available for agriculture.

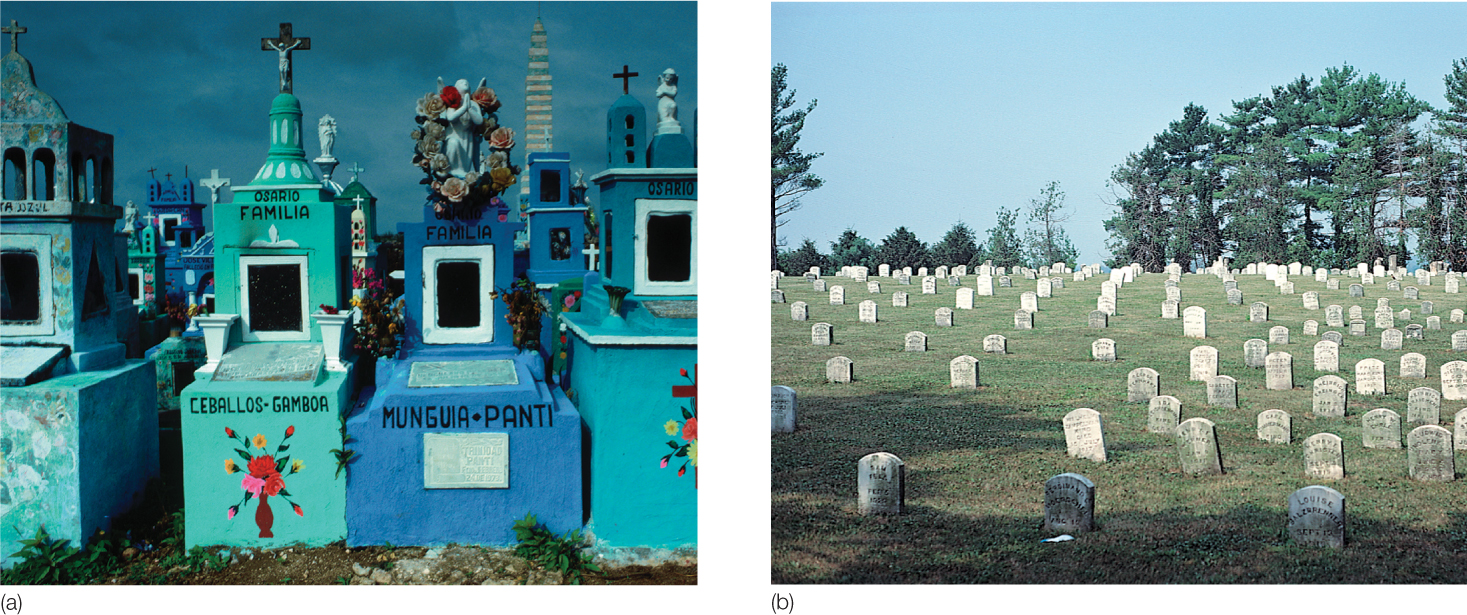

Christians also typically bury their dead in sacred places set aside for that purpose. These sacred places vary significantly from one Christian denomination to another. Some graveyards, particularly those of Mennonites and southern Protestants, are very modest in appearance, reflecting the reluctance of these groups to use any symbolism that might be construed as idolatrous. Among certain other Christian groups, such as Roman Catholics and the Orthodox Churches, cemeteries are places of color and elaborate decoration (Figure 7.34).

179

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.36

What do cemeteries in your community look like?

Cemeteries often preserve truly ancient cultural traits, because people as a rule are reluctant to change their practices relating to the dead. The traditional rural cemetery of the southern United States provides a case in point. Freshwater mussel shells are placed atop many of the elongated grave mounds, and rose bushes and cedars are planted throughout the cemetery. Research suggests that the use of roses may derive from the worship of an ancient pre-Christian mother goddess of the Mediterranean lands. The rose was a symbol of this great goddess, who could restore life to the dead. Similarly, the cedar evergreen is an age-old pagan symbol of death and eternal life, and the use of shell decoration derives from an animistic custom in West Africa, the geographic origin of slaves in the American South. Although the present Christian population of the South is unaware of the origins of their cemetery symbolism, it seems likely that their landscape of the dead contains animistic elements thousands of years old, revealing truly ancient beliefs and cultural diffusions.

Reflecting on Geography

Question 7.37

What is the most visible element of the religious landscape where you live?

Sacred Space

Sacred Space

sacred space An area recognized by one or more religious groups as worthy of devotion, loyalty, esteem, or fear to the extent that they become sought out, avoided, inaccessible to the nonbeliever, and/or removed from economic use.

Sacred spaces consist of natural and/or human-made sites that possess special religious meaning that is recognized as worthy of devotion, loyalty, fear, or esteem. By virtue of their sacredness, these special places might be avoided by the faithful, sought out by pilgrims, barred to members of other religions, or removed from economic use (see Figure 7.21). Often, sacred space includes the site of supposed supernatural events or is viewed as the abode of gods. Cemeteries are generally regarded as a type of sacred space. So is Mount Sinai, described by geographer Joseph Hobbs as endowed “with special grace,” where God instructed the Hebrews to “mark out the limits of the mountain and declare it sacred.” Conflict can result if two religions venerate the same space. In Jerusalem, for example, the Muslim Dome of the Rock, on the site where Muhammad is believed to have ascended to heaven, stands above the Western Wall, the remnant of the ancient Jewish temple (Figure 7.35). These two religions literally claim the same space as their holy site, which has led to conflict.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.38

Why is the location of the Dome of the Rock so likely to lead to a heightened degree of friction?

Sacred space is receiving increased attention in the world. In the mid-1990s, the internationally funded Sacred Land Project began to identify and protect such sites, 5000 of which have been cataloged in the United Kingdom alone. Included are such places as ancient stone circles, pilgrim routes, holy springs, and sites that convey mystery or great natural beauty. This last type falls into the category of mystical places: locations unconnected with established religion where, for whatever reason, some people believe that “extraordinary, supernatural things can happen.” Sometimes the sacred space of vanished ancient religions never loses—or later regains—the functional status of mystical place, which is what has happened at Stonehenge in England.

179

In his 1957 book The Sacred and the Profane, the renowned religious historian Mircea Eliade suggested that all societies, past and present, have sacred spaces. According to Eliade, sacred spaces are so important because they establish a geographic center on which society can be anchored. Through what he termed hierophany, a sacred space emerges from the profane, ordinary spaces surrounding it.

Religious Names on the Land

Religious Names on the Land

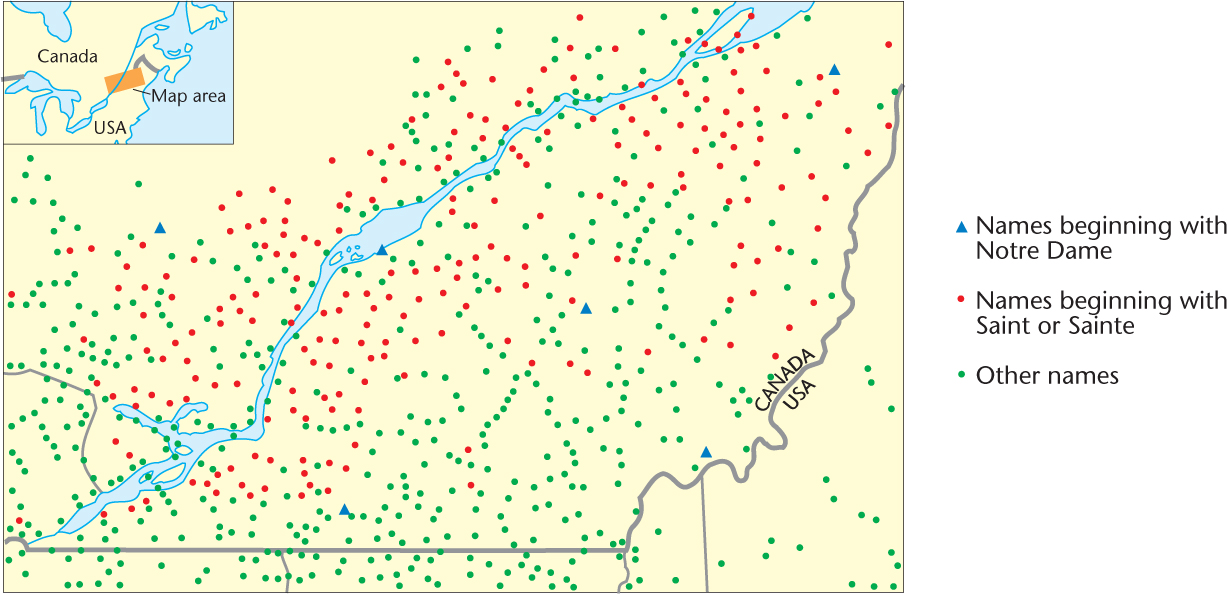

“St.-Jean,” “St.-Aubert,” “St.-Pamphile,” “St.-Adalbert”—so read the placards of town names as one drives from the St. Lawrence River south in Québec, paralleling the Maine border. All the saintliness is merely part of the French-Canadian religious landscape, as Figure 7.36 shows. The point is that religion often inspires the names that people place on the land. Within Christianity, the use of saints’ names for settlements is very common, especially in Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox areas, such as Latin America and French Canada. In areas of the Old World that were settled long before the advent of Christianity, saints’ names were often grafted onto pre-Christian names, as in Alcazar de San Juan in Spain, which combines Arabic and Christian elements.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.39

On this basis, where exactly would you draw the French Catholic–English Protestant border at the time of initial settlement? Is that border still in the same location today?

179

Toponyms in Protestant religions display less religious influence, but some imprint can usually be found. In the southern United States, for example, the word chapel as a prefix or suffix, as in Chapel Hill or Ward’s Chapel, is very common in the names of rural hamlets. Such names accurately convey the image of the humble, rural Protestant churches that are so common in the South.