Agricultural Diffusion

Agricultural Diffusion

How does the theme of cultural diffusion help us understand the spatial and cultural patterns of agricultural production and food consumption? Some of the variation among the agriculture regions we’ve discussed results from cultural diffusion. Agriculture and its many components are inventions; they arose as innovations in certain source areas and diffused to other parts of the world.

227

Origins and Diffusion of Plant Domestication

Origins and Diffusion of Plant Domestication

domesticated plant A plant deliberately planted, protected, cared for, and used by humans; it is genetically distinct from its wild ancestors as a result of selective breeding.

Agriculture probably began with the domestication of plants. A domesticated plant is one that is deliberately planted, protected, cared for, and used by humans. Such plants are genetically distinct from their wild ancestors because they result from selective breeding by agriculturists. Accordingly, they tend to be bigger than wild species, bearing larger and more abundant fruit or grain. For example, the original wild “Indian maize” grew on a cob only one-tenth the size of the cobs of domesticated maize.

Plant domestication and improvement constituted a process, not an event. It began as the gradual culmination of hundreds, or even thousands, of years of close association between humans and the natural vegetation. The first step in domestication was perceiving that a certain plant was useful, which led initially to its protection and eventually to deliberate planting.

Cultural geographer Carl Johannessen suggests that the domestication process can still be observed. He believes that by studying current techniques used by native subsistence farmers in places such as Central America, we can gain insight into the methods of the first farmers of prehistoric antiquity. Johannessen’s study of the present-day cultivation of the pejibaye palm tree in Costa Rica revealed that native cultivators actively engage in seed selection. All choose the seed of fresh fruit from superior trees, ones that bear particularly desirable fruit, as determined by size, flavor, texture, and color. Superior seed stocks are built up gradually over the years, with the result that elderly farmers generally have the best selections. Seeds are shared freely within family and clan groups, allowing rapid diffusion of desirable traits.

The widespread association of female deities with agriculture suggests that it was women who first worked the land. Recall the almost universal division of labor in hunting-gathering societies. Because women had day-to-day contact with wild plants and their mobility was constrained by childbearing, they probably played the larger role in early plant domestication.

Locating Centers of Domestication

Locating Centers of Domestication

When, where, and how did these processes of plant domestication develop? Most experts now believe that the process of domestication was independently invented at many different times and locations. Geographer Carl Sauer, who conducted pioneering research on the origins and dispersal of plant and animal domestication, was one of the first to propose this explanation.

Sauer believed that domestication did not develop in response to hunger. He maintained that necessity was not the mother of agricultural invention, because starving people must spend every waking hour searching for food and have no time to devote to the leisurely experimentation required to domesticate plants. Instead, he suggested this invention was accomplished by peoples who had enough food to remain settled in one place and devote considerable time to plant care. The first farmers were probably sedentary folk rather than migratory hunter-gatherers. He reasoned that domestication did not occur in grasslands or large river floodplains, because primitive cultures would have had difficulty coping with the thick sod and periodic floodwaters. Sauer also believed that the hearth areas of domestication must have been in regions of great biodiversity where many different kinds of wild plants grew, thus providing abundant vegetative raw material for experimentation and crossbreeding. Such areas typically occur in hilly districts, where climates change with differing sun exposure and elevation above sea level.

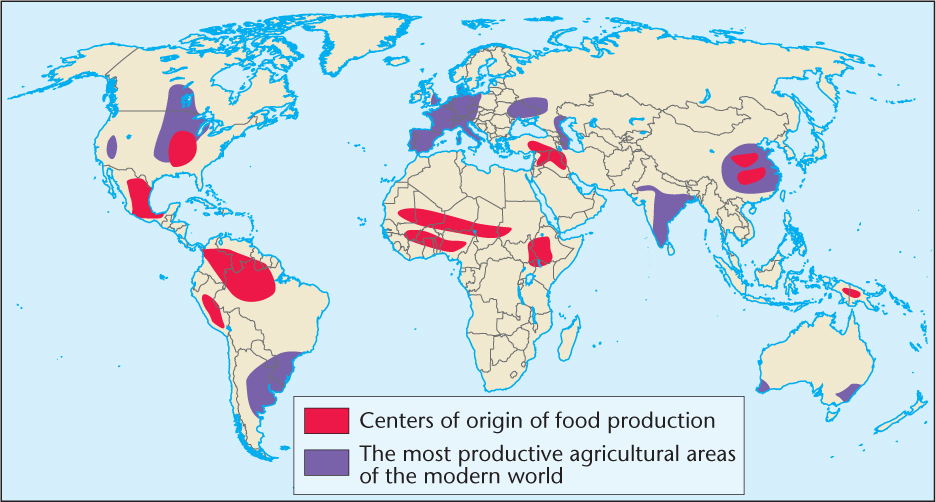

Geographers, archaeologists, and, increasingly, genetic scientists continue to investigate the geographic origins of domestication. Because the conditions conducive to domestication are relatively rare, most agree that agriculture arose independently in at most nine regions (Figure 8.16). All of these have made significant contributions to the modern global food system. For example, the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East is the origin of the great bread grains (wheat, barley, rye, and oats) that are so key to our modern diets. This region is also home to the first domesticated grapes, apples, and olives. China and New Guinea provided rice, bananas, and sugarcane, while the African centers gave us peanuts, yams, and coffee. Native Americans in Mesoamerica created another important center of domestication, from which came crops such as maize (corn), tomatoes, and beans. Farmers in the Andes domesticated the potato. While crop diffusions out of these nine regions have occurred over the millennia, the forces of globalization have now made even the rarest of local domesticates available around the world. Figure 8.17 shows the likely areas of domestication for several common crops.

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.18

Why is Southwest Asia, one of the first sites of agricultural domestication, no longer a leading agricultural area?

228

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.19

Why do you think that most ancient plant domestication took place in the mid-latitudes rather than in more extreme portions of the Northern or Southern hemispheres?

The dates of earliest domestication are continually being updated by new research findings. Until recently, archaeological evidence suggested that the oldest center is the Fertile Crescent, where crops were first domesticated roughly 10,000 years ago. However, domestication dates for other regions are constantly being pushed back by new discoveries. Most dramatically, in the Peruvian Andes archaeologists recently excavated domesticated seeds of squash and other crops that they dated to 9,240 years before the present. These seeds were associated with permanent dwellings, irrigation canals, and storage structures, suggesting that farming societies were established in the Americas 10,000 years ago, similar to the Fertile Crescent date.

Animal Domestication

Animal Domestication

domesticated animal An animal that depends on people for food and shelter and that differs from wild species in physical appearance and behavior as a result of controlled breeding and frequent contact with humans.

A domesticated animal is one that depends on people for food and shelter and that differs from wild species in physical appearance and behavior as a result of controlled breeding and frequent contact with humans. Animal domestication apparently occurred later in prehistory than did the first planting of crops—with the probable exception of the dog, whose companionship with humans appears to be much more ancient. Typically, people value domesticated animals and take care of them for some utilitarian purpose. Certain domesticated animals, such as the pig and the dog, probably attached themselves voluntarily to human settlements to feast on garbage. At first, perhaps, humans merely tolerated these animals, later adopting them as pets or as sources of meat.

The early farmers in the Fertile Crescent deserve credit for the first great animal domestications, most notably that of herd animals. The wild ancestors of major herd animals—such as cattle, pigs, horses, sheep, and goats—lived primarily in a belt running from Syria and southeastern Turkey eastward across Iraq and Iran to central Asia. Farmers in the Middle East were also the first to combine domesticated plants and animals in an integrated system, the antecedent of the peasant grain, root, and livestock farming described earlier. These people began using cattle to pull the plow, a revolutionary invention that greatly increased the acreage under cultivation. In other regions, such as southern Asia and the Americas, far fewer domestications took place, in part because suitable wild animals were less numerous. The llama, alpaca, guinea pig, Muscovy duck, and turkey were among the few American domesticates.

Exploration, Colonialism, and the Green Revolution

Exploration, Colonialism, and the Green Revolution

Over the past 500 years, European exploration and colonialism were instrumental in redistributing a wide variety of crops on a global scale: maize and potatoes from North America to Eurasia and Africa, wheat and grapes from the Fertile Crescent to the Americas, and West African rice to the Carolinas and Brazil.

229

The diffusion of specific crops continues, extending the process begun many millennia ago. The introduction of the lemon, orange, grape, and date palm by Spanish missionaries in eighteenth-century California, where no agriculture existed in the Native American era, is a recent example of relocation diffusion. This was part of a larger process of multidirectional diffusion. Eastern Hemisphere crops were introduced to the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa through the mass emigrations from Europe over the past 500 years. Crops from the Americas diffused in the opposite direction. For example, chili peppers and maize, carried by the Portuguese to their colonies in South Asia, became staples of diets all across that region (Figure 8.18).

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.20

How might the chili pepper have diffused so far and become so important in Asia?

In cultural geography, our understanding of agricultural diffusion focuses on more than just the crops; it also includes an analysis of the cultures and indigenous technical knowledge systems in which they are embedded. For example, geographer Judith Carney’s study of the diffusion of African rice (Oryza glaberrima), which was domesticated independently in the inland delta area of West Africa’s Niger River, shows the importance of indigenous knowledge. European planters and slave owners carried more than seeds across the Atlantic from Africa to cultivate in the Americas. The Africans taken into slavery, particularly women from the Gambia River region, had the knowledge and skill to cultivate rice. Slave owners actively sought slaves from specific ethnic groups and geographic locations in the West African rice-producing zone, suggesting that they knew about and needed Africans’ skills and knowledge.

green revolution The fairly recent introduction of high-yield hybrid crops and chemical fertilizers and pesticides into traditional agricultural systems, most notably paddy rice farming, with attendant increases in production and ecological damage.

Not all innovations involve expansion diffusion and spread wavelike across the land; less orderly patterns are more typical. The green revolution in Asia provides an example. The green revolution is a product of modern agricultural science that involves the development of high-yield hybrid varieties of crops, increasingly genetically engineered, coupled with extensive use of chemical fertilizers. The high-yield crops of the green revolution tend to be less resistant to insects and diseases, necessitating the widespread use of pesticides. The green revolution, then, promises larger harvests but ties the farmer to greatly increased expenditures for seed, fertilizer, and pesticides. It enmeshes the farmer in the global corporate economy. In some countries, most notably India, the green revolution diffused rapidly in the latter half of the twentieth century. By contrast, countries such as Myanmar (Burma) resisted the revolution, favoring traditional methods. An uneven pattern of acceptance still characterizes the paddy rice areas today.

230

The green revolution illustrates how cultural and economic factors influence patterns of diffusion. In India, for example, new hybrid rice and wheat seeds first appeared in 1966. These crops required chemical fertilizers and protection by pesticides, but with the new hybrids India’s 1970 grain production output was double its 1950 level. However, poorer farmers—the great majority of India’s agriculturists—could not afford the capital expenditures for chemical fertilizer and pesticides, and the gap between rich and poor farmers widened. Many of the poor became displaced from the land and flocked to the overcrowded cities of India, aggravating urban problems. To make matters worse, the use of chemicals and poisons on the land heightened environmental damage.

The widespread adoption of hybrid seeds has created another problem: the loss of plant diversity or genetic variety. Before hybrid seeds diffused around the world, each farm developed its own distinctive seed types through the annual harvest-time practice of saving seeds from the better plants for the next season’s sowing. Enormous genetic diversity vanished almost instantly when farmers began purchasing hybrids rather than saving seed from the last harvest. “Gene banks” have belatedly been set up to preserve what remains of domesticated plant variety, not just in the areas affected by the green revolution but also in the American Corn Belt and many other agricultural regions where hybrids are now dominant. In sum, the green revolution has been a mixed blessing.

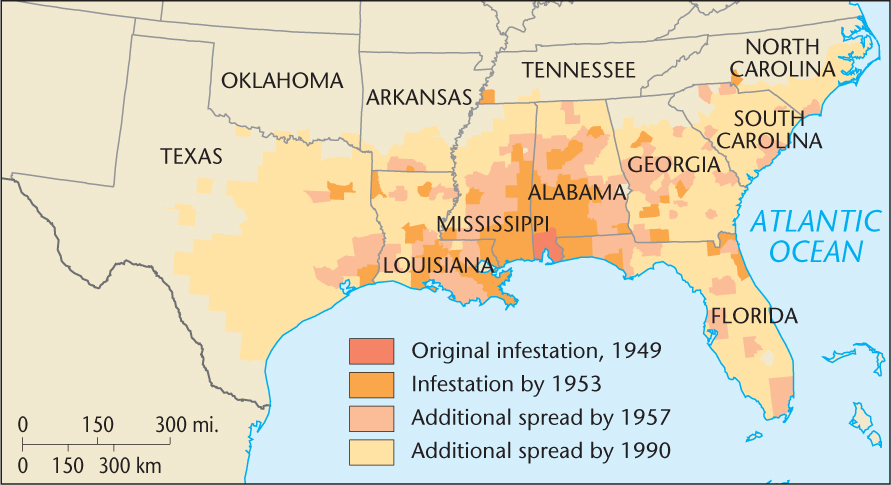

Not all diffusion related to agriculture has been intentional. In fact, accidental diffusion accomplished by humans probably occurs more commonly than the purposeful type. An example is the diffusion of the tropical American fire ant, so named because of its very painful sting (Figure 8.19). A shipload of plantation-grown bananas from tropical America accidentally brought the fire ant to Mobile, Alabama, in 1949, and a continuing relocation diffusion has since brought the fire ant across most of the American South. These vicious ants now endanger livestock and poultry raising, because swarms of them can attack and kill young animals.

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.21

How might this relocation diffusion have proceeded, and what barriers would the fire ant encounter? How did outliers develop? Why is this cultural diffusion?

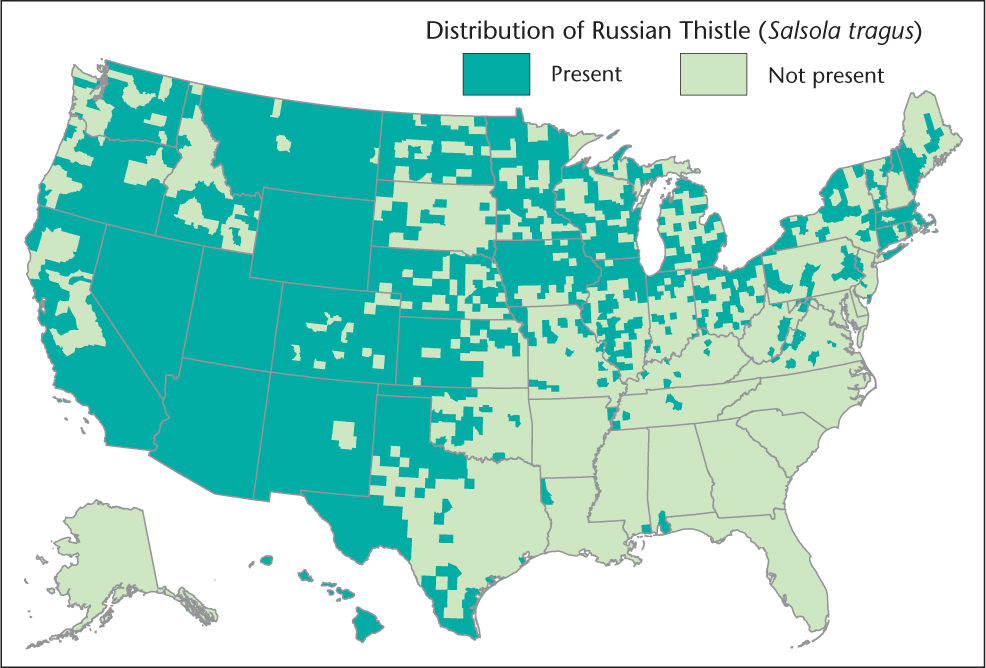

In addition to animal species, pest plant species have also diffused to regions where they now interfere with commercial agriculture. One such example is the unintentional spread of a plant commonly known as tumbleweed. Though perhaps seeming quite harmless, and maybe even picturesque when viewed rolling across rural landscapes of the American West, this Russian form of the thistle plant is actually an invasive plant species. It diffused to the United States from Asia over 100 years ago, but in recent decades it has become increasingly troublesome to farmers and livestock producers as it has spread throughout most of the western United States and continues to diffuse eastward (Figure 8.20). This spread has been possible because, in order to survive, the tumbleweed plant dries and detaches from the location where it grows and rolls across the landscape to disburse its seeds. In doing so, the tumbleweed often acts as a vehicle for other non-native pest plant and insect species that are picked up within it as it tumbles. As the rolling plants eventually come to rest and pile up along fences and buildings in agricultural areas, they cause extensive and expensive structural damage. Tumble-weeds have also been known to contribute to the spread of wildfires, further endangering valuable agricultural lands. The plant can be a hazard to the general public as well, as it is credited with causing numerous road accidents.

Thinking Geographically

Question 8.22

What physical environmental factors do you think may have slowed the spread of the tumbleweed into the southeastern United States?

Reflecting on Geography

Question 8.23

Agricultural diffusion continues today. You participate in it when you decide whether to eat a food you have not previously known. What goes through your mind in, say, an ethnic restaurant when you decide to try, or not to try, a new food?