Diffusion of Industry and Services

Diffusion of Industry and Services

How can we understand the changing locations of industrial activities? The theme of cultural diffusion permits us to begin answering the question. Perhaps the most basic issue is the diffusion of the industrial revolution itself.

Origins of the Industrial Revolution

Origins of the Industrial Revolution

Until the industrial revolution, society and culture remained overwhelmingly rural and agricultural. Cities certainly existed, as centers of political power, education, and innovation, but the majority of people lived in the countryside working to procure food through agriculture. To be sure, secondary industry already existed in this setting. For as long as Homo sapiens has existed, we have fashioned tools, weapons, utensils, clothing, and other objects, but traditionally these items were made by hand, laboriously and slowly. Before about 1700, most such manufacturing was carried out in two rather distinct systems: cottage industry and guild industry.

cottage industry A traditional type of manufacturing before the industrial revolution, practiced on a small scale in individual rural households as a part-time occupation and designed to produce handmade goods for local consumption.

guild industry A traditional type of manufacturing before the industrial revolution, involving handmade goods of high quality manufactured by highly skilled artisans who resided in towns and cities.

industrial revolution A series of inventions and innovations, arising in England in the 1700s, that led to the use of machines and inanimate power in the manufacturing process.

Cottage industry, by far the more common system, was practiced in farm homes and rural villages, usually as a sideline to agriculture. Objects for family use were made in each household, usually by women. Additionally, most villages had a cobbler, miller, weaver, and smith, all of whom worked part-time at these trades in their homes. Skills passed from parents to children with little formality.

By contrast, the guild industry consisted of professional organizations of highly skilled, specialized artisans engaged full-time in their trades and based in towns and cities. Membership in a guild came after a long apprenticeship, during which the apprentice learned the skills of the profession from a master. Although the cottage and guild systems differed in many respects, both depended on hand labor and human power.

The industrial revolution began in England in the early 1700s. First, machines replaced human hands in the fashioning of finished products, rendering the word manufacturing (meaning “made by hand”) technically obsolete. No longer would the weaver sit at a hand loom and painstakingly produce each piece of cloth. Instead, large mechanical looms were invented to do the job faster and cheaper. Second, human power gave way to various other forms of power: water power, the burning of fossil fuels, and later electricity and the energy of the atom fueled the machines. Men and women, once the producers of handmade goods, became tenders of machines.

The initial breakthrough came in the secondary, or manufacturing, sector. More specifically, it occurred in the British cotton textile cottage industry, centered at that time in the district of Lancashire in northwestern England. At first the changes were on a small scale. Mechanical spinners and looms were invented, and flowing water was harnessed to drive the looms. During this stage, manufacturing industries were still largely rural and dispersed, because they were tethered to their individual power sources. Sites where rushing streams could be found, especially those with waterfalls and rapids, were ideal locations. Later in the eighteenth century, the invention of the steam engine provided a better source of power, and a shift away from water-powered machines occurred. The steam engine also allowed textile producers and other manufacturers to move away from their power source—water—and to relocate instead in cities that better suited their labor and transportation needs. Manufacturing enterprises generally began to cluster together in or near established cities.

Traditionally, metal industries had been small-scale, rural enterprises, carried out in small forges situated near ore deposits. Forests provided charcoal for the smelting process. The chemical changes that occurred in the making of steel remained mysterious even to the craftspeople whose job it was, and much ritual, superstition, and ceremony were associated with steel making. Techniques had changed little since the beginning of the Iron Age, 2500 years earlier. The industrial revolution radically altered all of this. In the eighteenth century, a series of inventions by iron makers living in Coalbrookdale, in the English Midlands, allowed the old traditions, techniques, and rituals of steel making to be swept away and replaced by a scientific, large-scale industry. Coke, nearly pure carbon derived from high-grade coal, was substituted for charcoal in the smelting process. Large blast furnaces replaced the forge, and efficient rolling mills took the place of hammer and anvil. Mass production of steel resulted, and that steel was used to make the machines that in turn created more industry.

257

Primary industries also were revolutionized. Coal mining was the first to feel the effects of the new technology. The adoption of the steam engine required huge amounts of coal to fire the boilers, and the conversion to coke in the smelting process further increased the demand for coal. New mining techniques and tools were invented, and coal mining became a large-scale, mechanized industry. However, coal, which is heavy and bulky, was difficult to transport. As a result, manufacturing industries that relied heavily on coal began flocking to the coalfields to be near the supply. Similar modernization occurred in the mining of iron ore, copper, and other metals needed by rapidly growing industries.

The industrial revolution also affected the service industries, most notably in the development of new forms of transportation. Traditional wooden sailing ships gave way to steel vessels driven by steam engines, and later railroads became more prevalent. The need to move raw materials and finished products from one place to another both cheaply and quickly was the main stimulus that led to these transportation breakthroughs. Without them, the impact of the industrial revolution would have been minimized.

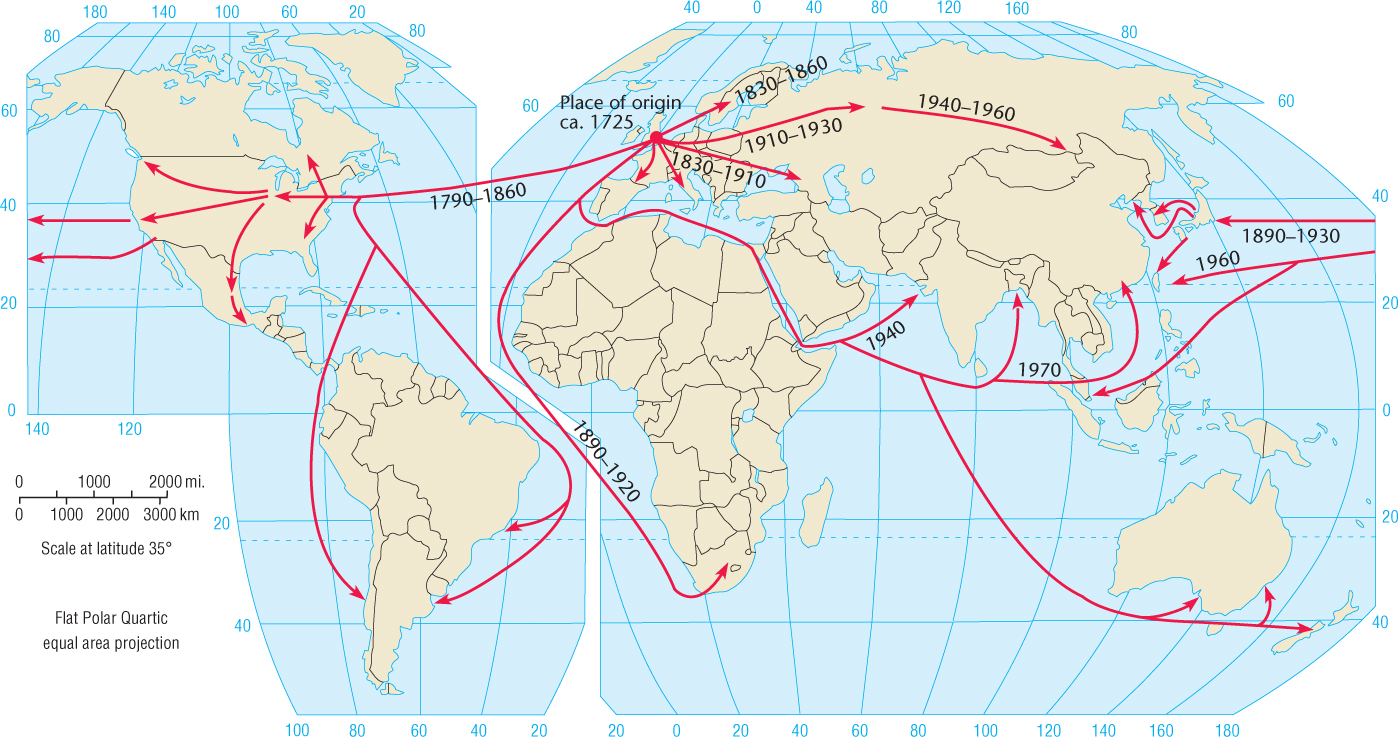

Once in place, the railroads and other innovative modes of transport associated with the industrial revolution fostered additional cultural diffusion (Figure 9.7). Ideas spread more rapidly and easily because of this efficient transportation network. In fact, the industrial revolution itself was diffused through these new transportation technologies.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.7

Can you find evidence of both contagious and hierarchical diffusion?

Diffusion of the Industrial Revolution

Diffusion of the Industrial Revolution

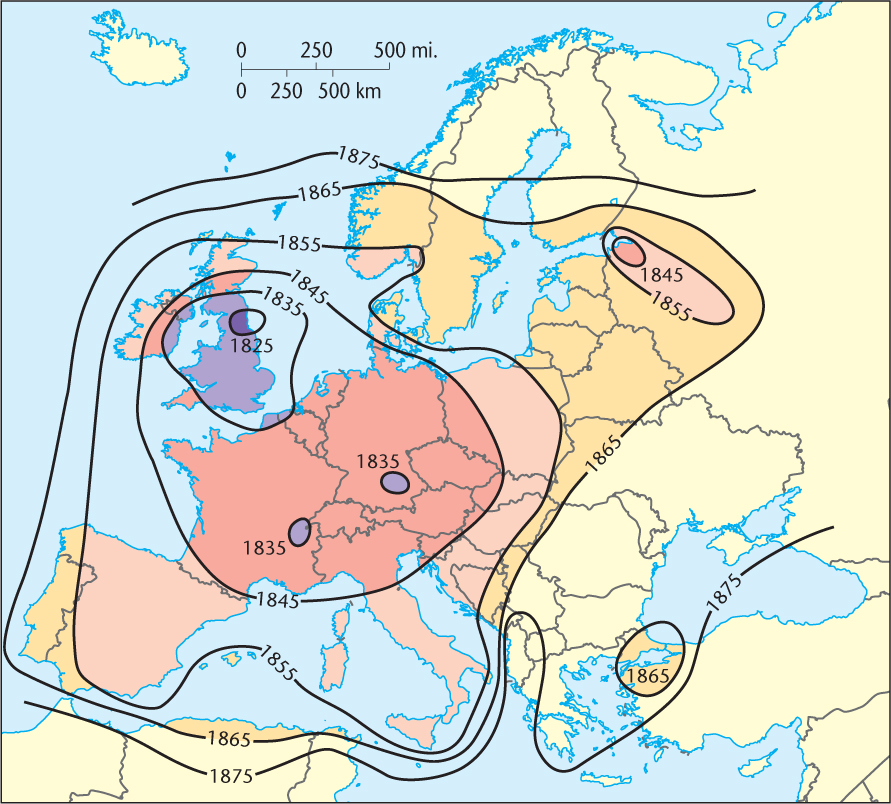

Great Britain maintained a virtual monopoly on the industrial revolution well into the 1800s. Indeed, the British government actively tried to prevent the diffusion of the various inventions and innovations that made up the industrial revolution. After all, they gave Britain an enormous economic advantage and contributed greatly to the growth and strength of the British Empire. Nevertheless, this technology finally diffused beyond the bounds of the British Isles (Figure 9.8), with continental Europe feeling the impact first. In the last half of the nineteenth century, the industrial revolution took firm root in the coalfields of Belgium, Germany, and other nations of northwestern and central Europe. The diffusion of railroads in Europe provides a good index of the spread of the industrial revolution there. The United States began rapid adoption of this new technology in about 1850, followed half a century later by Japan, the first major nonwestern nation to undergo full industrialization. In the first third of the twentieth century, the diffusion of industry and modern transport spilled over into Russia and Ukraine.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.8

Why might the industrial revolution have originated in so small a country?

Until fairly recently, most of the world’s manufacturing plants were clustered together in pockets within several regions, particularly Anglo-America, Europe, Russia, and Japan. In the United States, secondary industries once clustered mainly in the northeastern part of the country, a region referred to as the American Manufacturing Belt (see Figure 9.4). Across the Atlantic, manufacturing occupied the central core of Europe, which was surrounded by a less industrialized periphery throughout the mid-twentieth century. Japan’s industrial complex was located along the shore of the Inland Sea and throughout the southern part of the country.

258

The Locational Shifts of Secondary Industry and Deindustrialization

The Locational Shifts of Secondary Industry and Deindustrialization

transnational corporation A company that has international production, marketing, and management facilities.

The diffusion of industrialization around the globe continues today, but not in the same manner in which the industrial revolution spread from England to Europe, the United States, and Japan. During the diffusion of industry in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there were very few global transportation or communication networks. Therefore, for the most part, industries were predominantly national in scale. All of their activities were located within national boundaries, from their headquarters to their supply of raw materials to the labor for their plants. However, by the mid to late twentieth century, with the advent of new communication and transportation technologies such as telephones, jet planes, and computers, it became possible to develop industries that could locate different parts of their operation (labor, power, materials, markets, and so on) in places beyond national borders. This has allowed manufacturing companies, for example, to seek out the best locations for their plants without regard to national boundaries, in effect spreading industrialization around the world. Today, transnational corporations that are headquartered in London, for example, might have their manufacturing facilities in Vietnam and Mexico, while their materials might be supplied by Indonesia.

technopole A center of high-tech manufacturing and information-based industry.

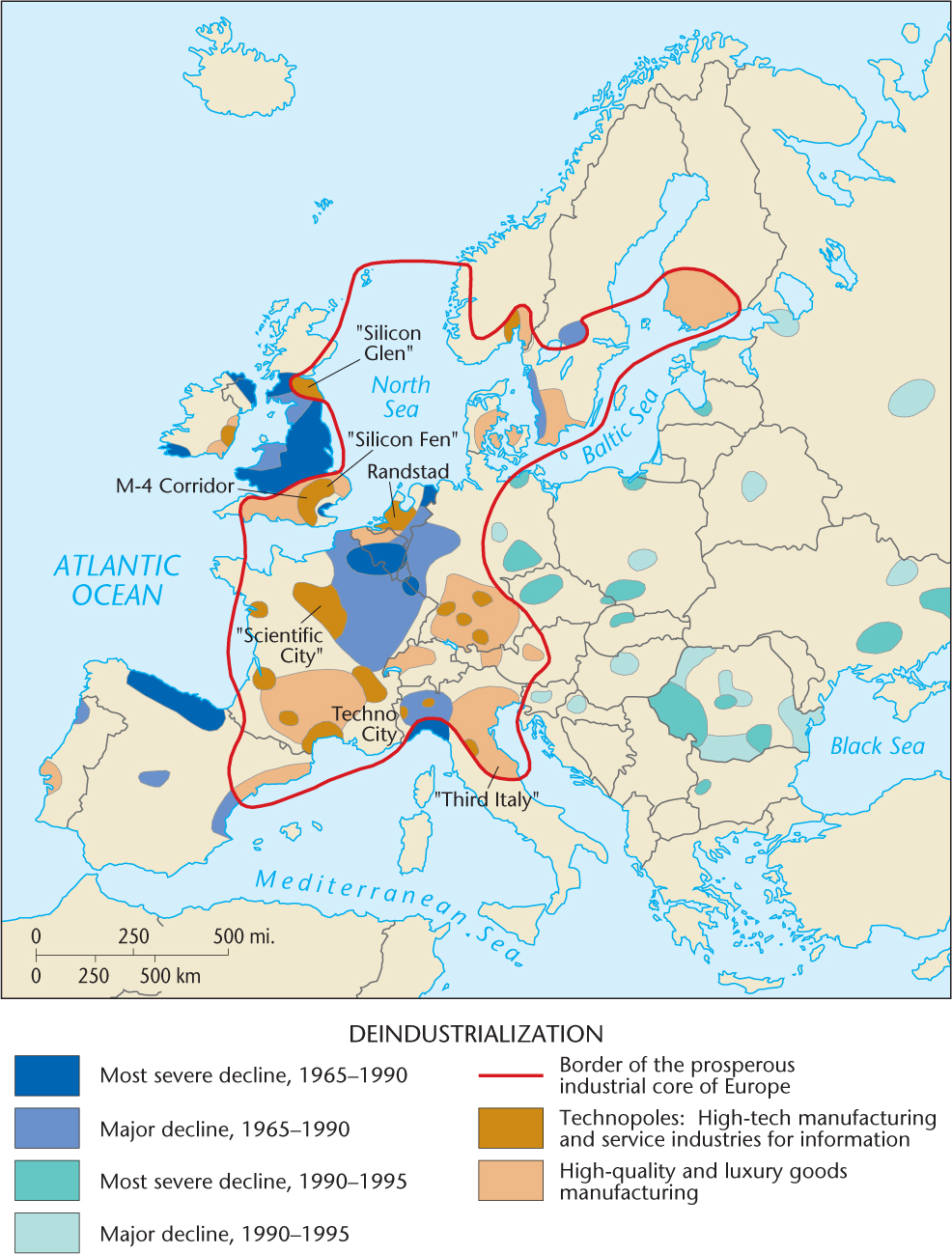

Although the manufacturing dominance of the developed countries persists, a major global geographical shift is under way. In virtually every one of these countries, much of the secondary sector is in marked decline, especially traditional mass-production industries, such as steel making, that require a minimally skilled blue-collar workforce. In such districts, factories are closing and blue-collar unemployment rates are at the highest level since the Great Depression of the 1930s. In the United States, for example, where manufacturing employment began a relative decline around 1950, nine out of every 10 new jobs in recent years have been lowpaying service positions. The manufacturing industries surviving and now booming in the core countries are mainly those requiring a highly skilled or artisanal workforce, such as high-tech firms and companies producing high-quality consumer goods. Because it is often difficult for the blue-collar workforce to acquire the new skills needed in such industries, many old manufacturing districts lapse into deep economic depression. Moreover, high-tech manufacturers employ far fewer workers than heavy industries and tend to be geographically concentrated in very small districts, sometimes called technopoles (see Figure 9.4).

deindustrialization The decline of primary and secondary industry, accompanied by a rise in the service sectors of the industrial economy.

The word deindustrialization refers to the decline of primary and secondary industry, usually accompanied by a rise in the service sectors. Deindustrialization is responsible for the decline and fall of once-prosperous factory and mining areas, such as the east and west Midlands of England (Figure 9.9). Manufacturing industries lost by the core countries relocate to newly industrializing lands that were once the periphery. South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Brazil, Mexico, coastal China, the Philippines, and parts of India, among others, have experienced a major expansion of manufacturing. Geographers and others often refer to these countries as newly industrializing countries (NICs). Companies move to these areas for many different reasons, including cheaper labor costs, lower environmental standards, and the relative proximity of these plants to their expanding markets outside the traditional core. Yet even with this massive diffusion of industry, the geographic pattern of the world’s manufacturing sites remains quite uneven. Table 9.1 reflects this unevenness, as long-dominant manufacturing regions in North America, Europe, and East Asia are still represented among countries leading in gross value added (GVA), the value created by production processes. Meanwhile, many parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia lag well behind. It should be noted that GVA can be calculated in different ways, and it can include varying production activities from country to country. This lack of uniformity makes international comparisons of GVA potentially misleading. Nevertheless, over time, the data can be useful in analyzing the maturity of a country’s manufacturing sector. By analyzing GVA along with other economic measures, we can see that the United States, China, and Japan account for a large segment of the world’s manufacturing output.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.9

Why might the industrial districts in decline not have shared the new prosperity? Why did eastern Europe fall so far behind?

259

260

Reflecting on Geography

Question 9.10

Identify and discuss some of the reasons that the “old” manufacturing core still retains its dominance in the global manufacturing system.

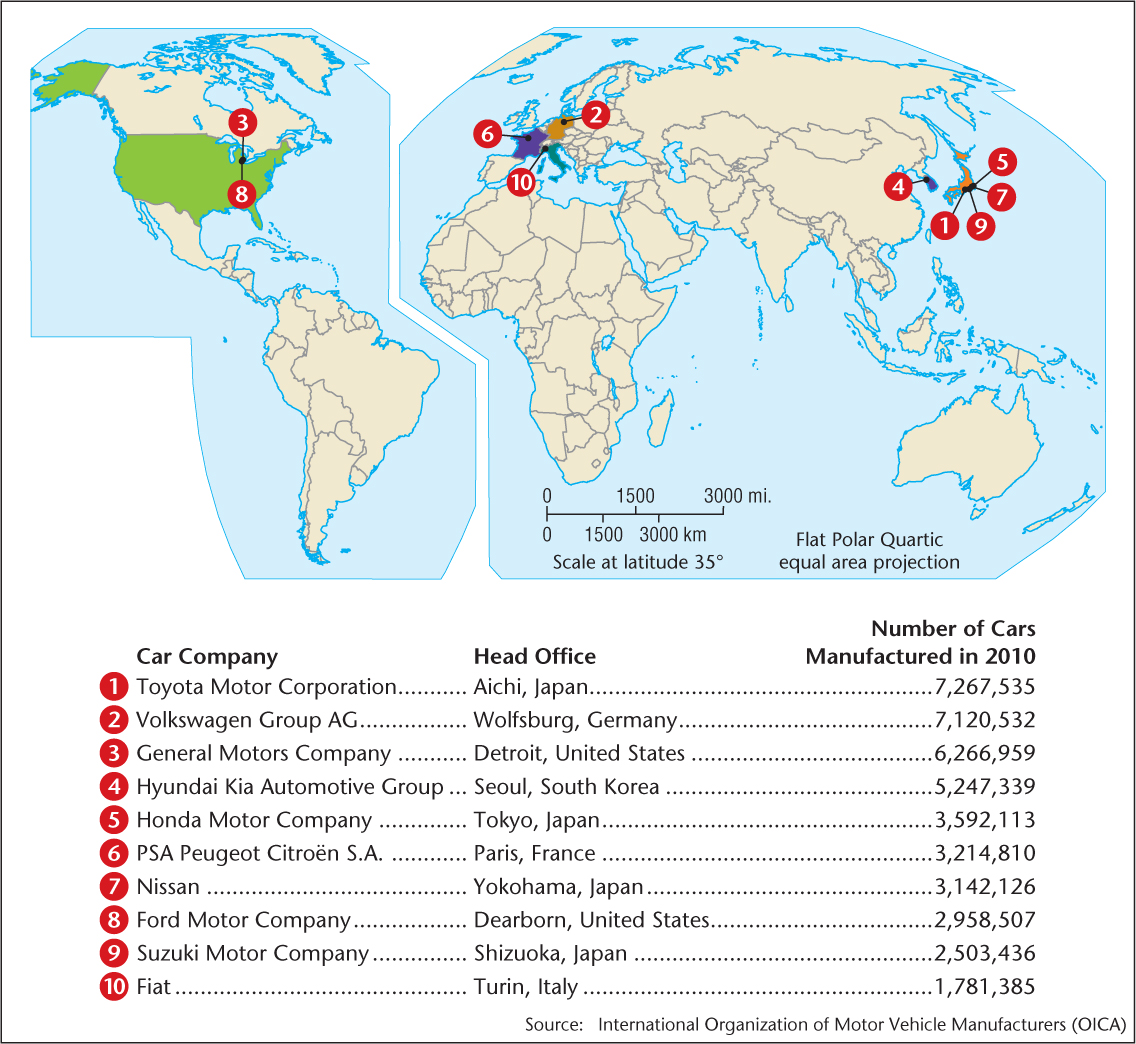

A good example of a transnational industry is the automobile industry. In contrast to earlier decades of automobile manufacturing, millions of cars are now produced outside of the United States every year. In fact, in 2010, the top two automobile producers in the world were located in Asia and Europe, respectively (Figure 9.10). Only two of the current top 10 auto manufacturers are headquartered in the United States. In comparison to the automobile industry, the major manufacturing plants of which are scattered over several world regions, the manufacturing facilities of the textile and garment industries are disproportionately located in China, which has a large pool of relatively low-wage workers and a government eager to offer incentives. However, not all types of textile production are located in China. While the bulk of mass-produced items are made in China, much high-end designer clothing tends to be produced in different places and under different conditions. This is all part of the process of globalization.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.11

Why do you think that automobile manufacturing has not become established to any large degree in South America, Africa, or much of Asia?

Table 9.1:

Gross Value Added by Country, 2010 (in U.S. Trillions)

| Rank | Country | 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 13.45 |

| 2 | China | 5.93 |

| 3 | Japan | 5.44 |

| 4 | Germany | 2.93 |

| 5 | France | 2.30 |

| 6 | United Kingdom | 2.01 |

| 7 | Italy | 1.84 |

| 8 | India* | 1.28 |

| 9 | Russian Federation | 1.27 |

| 10 | Spain | 1.27 |

| 11 | Mexico | 1.00 |

| 12 | Australia* | 0.93 |

| 13 | Korea | 0.91 |

| 14 | Indonesia | 0.70 |

| 15 | Netherlands | 0.69 |

| 16 | Turkey | 0.65 |

| 17 | Switzerland | 0.49 |

| 18 | Belgium | 0.41 |

| 19 | Poland | 0.41 |

| 20 | Sweden | 0.40 |

| *2009 Data | ||

| Note: “Gross value added” is defined as the additional value created by a production process. Based on data from OECD (2012), OECD.Stat, (database). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00285-en. | ||

261

postindustrial phase A society characterized by the dominance of the service sectors of economic activity.

The decline of primary and secondary industries in the older developed core, or deindustrialization, has ushered in an era in these regions widely referred to as the postindustrial phase, a phrase used to describe a society characterized by the dominance of the service sectors. Both the United States and Canada are in the postindustrial phase, as are most of Europe and Japan.