Industrial-Economic Landscapes

Industrial-Economic Landscapes

In what ways have economic activities altered the cultural landscape? It is difficult to look at any particular landscape and not see some evidence of the production, circulation, and consumption of goods and services. Factory buildings of course provide an obvious example, but perhaps less obvious are the spaces where goods and services circulate (highways, trains, airports, for example) and where they are consumed (for example, malls, shops, offices). Economic landscapes, then, are prominent visible features of our surroundings and form part of daily life.

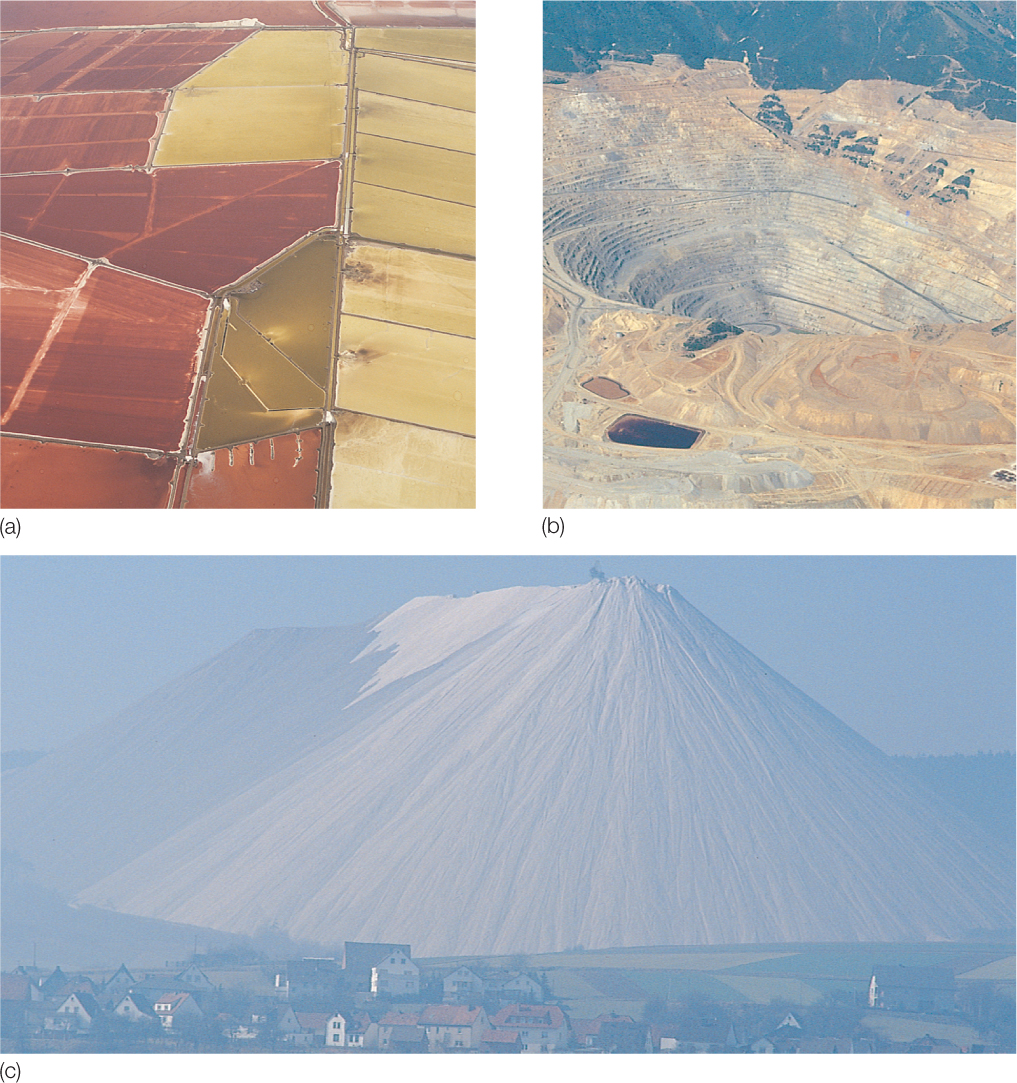

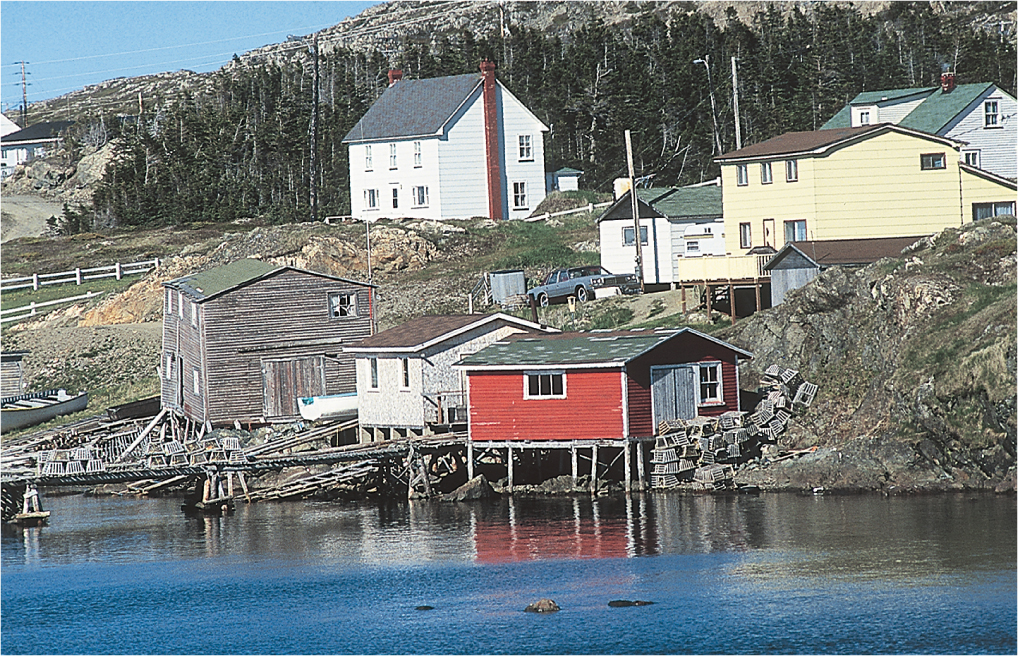

Each level of industrial activity produces its own distinctive landscape. Primary industries exert perhaps the most drastic impact on the land. The resulting landscapes contain slag heaps, clear-cut commercial forests, strip-mining scars, open-pit mines, and oil derricks (Figure 9.20). The destruction of nature is less apparent in other types of primary industrial landscapes. The fishing villages of Portugal or Newfoundland even attract tourists (Figure 9.21). In still other cases, efforts are made to restore the preindustrial landscape. Examples include the establishment of artificial grasslands in old strip-mining areas of the American Midwest and the creation of recreational ponds in old mine pits along interstate highways.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.22

What are the environmental implications of these landscapes?

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.23

What problems might such a landscape also suggest?

272

Among the most obvious features of the landscapes of secondary industry, or manufacturing, are factory buildings. Early- to mid-nineteenth-century industrial landscapes are easy to identify, because the technologies that ran these factories were reliant on water power. Hence, the mill buildings that housed the machinery were designed in linear form to take full advantage of the turbines that were connected to waterwheels. What’s more, given this locational requirement, these mill complexes were most often built in rural areas. Entire communities, most often with housing for the workers, were thus constructed along with the mills. These mill towns dotted the landscape of England, Scotland, and New England, the site of the first industrial developments in the United States (Figure 9.22). Later—as water power was supplanted by steam, coal, and then electric power—factories were located near urban areas, taking advantage of the housing supply already there and the proximity to a large consumer base. These industrial landscapes were often located at the edge of downtowns, lining the railroad routes into the city, and were surrounded by working-class housing. In the second half of the twentieth century—with the development of the interstate highway system and the trucking industry, as well as the switch to high-tech industries such as electronics—industrial landscapes took on a different form. Factories began to move to industrial parks at interstate exchanges, and their architecture began to resemble other types of mass-produced architecture, such as big-box stores (Figure 9.23).

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.24

What accounts for the footloose nature of the textile industry?

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.25

Are there any visual clues here that this structure is a factory rather than a big-box store?

Given the degree of deindustrialization in certain parts of the old core industrial regions, it is not surprising that many of these factory complexes, particularly those that date from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, are derelict or are being retrofitted for housing or commercial uses. Others now house historical museums depicting past industrial technologies and ways of life. Lowell, Massachusetts, an early (mid-nineteenth-century) planned industrial town that produced textiles, is now the site of a national park. A good percentage of its factories, canals, and housing complexes have been preserved and can be toured by visitors. In Great Britain, many sites of industrial history are now preserved as museums. New Lanark, located outside Glasgow in Scotland, is now a World Heritage Site and provides a particularly interesting example of an industrial landscape, given that it was originally established by Robert Owen as a utopian community. He included in his planning good schools, housing, and even a cooperative food store in order to create a benevolent community of workers (Figure 9.24).

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.26

Compare these buildings to the workers’ dormitory in Figure 9.25, and consider the changes that have occurred (or haven’t occurred) in the provision of housing for industrial workers.

273

In other parts of the world industrial landscapes are far from derelict; they are, in fact, being built anew. In Southeast Asia, China, and Mexico, large industrial landscapes are under construction. Some, like the maquiladoras, are similar to the early mill towns in that they too are being constructed in nonurban sites without housing or other infrastructure. In the maquiladoras, as well as in many industrial regions of China, housing comes either in the form of dormitories or in informal squatter settlements (Figure 9.25).

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.27

Compare this image to Figure 9.24.

274

Service industries, too, produce a cultural landscape. Its visual content includes elements as diverse as high-rise bank buildings, hamburger stands, silicon landscapes, gasoline stations, and the concrete and steel webs of highways and railroads. Some highway interchanges can best be described as a modern art form, but perhaps the aesthetic high point of the industrial landscape is found in bridges, which are often graceful and beautiful structures. The massive investment in these transportation systems has even changed the way we view the landscape. As geographer Yi-Fu Tuan commented, “In the early decades of the twentieth century vehicles began to displace walking as the prevalent form of locomotion, and street scenes were perceived increasingly from the interior of automobiles moving staccato-fashion through regularly spaced traffic lights.” Los Angeles provides perhaps the best example of the new viewpoints provided by the industrial age. Its freeway system allows individual motorists to observe their surroundings at nonstop speeds. It also allows the driver to look down on the world. The view from the street, on the other hand, is not encouraged. In some areas of Los Angeles, streets actually have no sidewalks at all, so the pedestrian viewpoint is functionally impractical. In addition, the shopping street is no longer scaled to the pedestrian—Los Angeles’s Ventura Boulevard extends for 15 miles (24 kilometers).

Producer services related to financial activities, such as legal services, trade, insurance, and banking, traditionally were located in high-rise buildings in urban centers, but with suburbanization they have taken on a nonurban form. Many are now located in five- or six-story buildings along the interstates surrounding cities in what we’ve called high-tech corridors (Figure 9.26). Other producer service industries choose to maintain their downtown location for symbolic reasons. Some consumer services, particularly retailing, have created distinctive and, within the American context at least, socially important landscapes. Shopping malls are now dominant features of the North American suburb and often serve as catalysts to suburban land development, in effect creating entirely new landscapes, all geared toward consumption. Chapter 11 provides more details about these new and emerging landscape elements.

Thinking Geographically

Question 9.28

Why are these buildings set back off the road?