Chapter Introduction

CHAPTER 4

WHY WAS THE GREAT NEWSPAPER HEIST SO EASY?

Diminishing Marginal Utility and the Price Elasticity of Demand

In the 1980s, members of a fraternity at Michigan State University allegedly tied a pledge to a flagpole and slung mud on him. When the school newspaper published an unflattering photograph of the incident, thousands of copies of the newspaper went missing from distribution sites across campus. Someone had stolen the papers in an effort to keep the photo from being seen. Why had this theft been so easy? Sodas and candy bars cost as much as newspapers, but candy vending machines have elaborate mechanisms to prevent the removal of more than 1 item at a time. In contrast, newspaper vending machines allow the entire stack of papers to be taken after only 1 has been purchased, and school newspapers are often set out for free with little fear that someone will take the whole pile. This chapter explains how differing demands for various goods shape public policy and pricing decisions, as well as the design of vending machines. (By the way, even when theft is easy, crime doesn’t pay: The great newspaper heist caught the attention of newspapers across the country, and the photo of the dirty deed was republished from coast to coast for millions to see.)

THE MEANING OF LIFE

Economics has been called the dismal science,1 but it is really about the meaning of life. The Dalai Lama, exiled Tibetan leader and winner of the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize, writes in The Meaning of Life (2000, p. 29) that “it is a fact that everybody wants happiness.” The demand curve is simply a reflection of what makes us happy. The happier something makes us, the more we would be willing to exchange for it and the higher is our demand for it. Other things being equal, relatively high demand boosts prices and spurs suppliers to provide more of what pleases us. This chapter explains the demand curve’s foundation in measures of happiness and some of the reasons for the demand curve’s importance.

There is no obvious measure of happiness. The benefits that consumers receive from goods and services could be measured, for example, in terms of giggles, goose bumps, satisfaction points, or smiles. Economists measure happiness in terms of utility, which they measure in units called utils. In agreement with the Dalai Lama, economists assume that human nature guides individuals to seek happiness. In economic terminology, the quest to be as happy as possible means that it is better to have more utils than fewer and that we make decisions with the goal of maximizing our utility.

The sources of utility are subjective and result from personal tastes and preferences. Some people like sushi; others like their fish cooked. Some people like to shoot wild animals with cameras; others prefer to use rifles. These differences and the arbitrary nature of utility measurement make interpersonal utility comparisons impossible because there is no concrete gauge for such comparisons. You might report a gain of 100 utils from a day at the Five Flags theme park, whereas I reported a gain of 1,000 utils, but who is to say that I really gained more happiness than you did? Fortunately, the simple fact that more utils are better is sufficient in many important areas of economic analysis, some of which this chapter explores.

The additional utility gained from 1 more unit of a good is called the marginal utility of that good. According to the “law” of diminishing marginal utility, each additional unit of a good or service consumed provides less happiness—

EXAMPLES OF MARGINAL UTILITY AND DEMAND

Variations in the marginal utility of goods yield a varied crop of demand curves. A dollar will get you a soda or a can of soup, but the average American purchases 19 cans of soda and only 1 can of soup per week.2 For a typical consumer of refrigerators, the marginal utility (and, therefore, demand) starts relatively high and plummets after a quantity of 1. Thus, owners of a good refrigerator are unlikely to respond to even the deepest discounts in refrigerator prices. For candy bars, marginal utility and demand typically begin low and fall gradually as more bars are consumed, depending on the sweet tooth of the consumer. The characteristic demand for these goods explains why you’ll see “buy one, get one free” sales on Rolo’s chocolates and RC Colas but not on refrigerators: The marginal utility of the second fridge doesn’t warrant the promotion.

2 See www.bottledwater.org/

The marginal utility of newspapers is similar to that of refrigerators but lower. Your first copy of the daily newspaper provides the latest information on current events, entertainment, sports, and any storms that are brewing. All this gives the first newspaper considerable marginal utility. Consequently, millions of people buy subscriptions to newspapers. For example, about 1.8 million people pay $200 a year to subscribe to the Wall Street Journal. Here’s the twist: The average U.S. citizen consumes 49.2 gallons of soft drinks, 67 pounds of poultry, and 12,406 kilowatt-

Suppose the value of your marginal utility from today’s newspaper drops from $3 for the first newspaper to 0 for the second. This precipitous drop in marginal utility means that the quantity of papers demanded is unlikely to change when the price changes. A change from one price above $3 to another price above $3 would not trigger a purchase because both prices exceed a newspaper’s value to you. A change from one price below $3 to another price below $3 would not cause you to buy another newspaper because you don’t want a second paper at any price. Only if the price changed from above $3 to below $3 would any change take place: You would then make your first purchase. Once you’ve shelled out the cash to open the box and gain access to the newspapers, you have no interest in a second copy.

When the value of multiple copies increases as the result of, say, a desire to protest or cover up a story, newspapers are especially vulnerable to large-

PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND

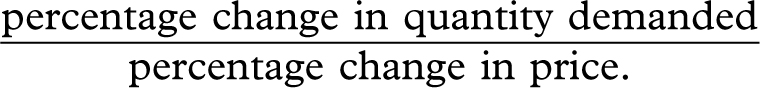

The rate at which marginal utility falls as the quantity of a good rises determines other information critical to economists and businesses: consumers’ sensitivity to price changes. The level of this sensitivity helps determine whether a price hike will cause many customers to leave or profits to leap. Economists call the sensitivity of quantity demanded to price changes the price elasticity of demand. If you buy a lot more movie DVDs when the price goes down a little, and a lot fewer when the price goes up, your demand for DVDs is relatively elastic. If you persist in purchasing only 1 cell phone when the price goes up or down, your demand for cell phones is inelastic. To be precise, the value of the price elasticity of demand is

Consider a few real-

3 Because the price change is negative and the quantity change is positive, the price elasticity is actually a negative number. However, for simplicity, most economists discuss elasticities in absolute value terms, meaning that the negative signs are removed.

Don’t make the common mistake of confusing elasticity with the slope of the demand curve. At a given quantity and price, a steep demand curve is less elastic than a relatively flat demand curve, but there’s more to elasticity than slope. The slope of the demand curve is found by dividing the change in price by the change in quantity; elasticity is found by dividing the percentage change in quantity by the percentage change in price. A straight demand curve with a constant slope has a different elasticity at every point because, even though price and quantity are changing at a constant rate, the percentage changes in price and quantity are not constant. For example, an increase in quantity from 100 to 101 represents a 1 percent increase in quantity, whereas an equivalent increase in quantity by 1 from 10 to 11 represents a 10 percent increase in quantity. Thus, moving rightward along a straight demand curve, the slope stays the same but elasticity decreases as the percentage change in quantity falls and the percentage change in price rises.

In general, the quantity demanded is more responsive to price changes, and, therefore, more elastic, for goods and services that

have many substitutes

are not essential to daily life

require a large share of our wealth

can be purchased at a later time

The opposite is also true: Goods and services have a relatively inelastic demand when they have few substitutes, are necessities, require a small share of our wealth, or must be purchased without delay.

Consider the price elasticity of demand for taxi rides in New York City and for the New York Times. Substitutes for taxis include buses, subways, bikes, and feet. Many New Yorkers don’t own cars, getting around just fine with alternative forms of transportation and considering it a luxury to hire a taxi. A taxi ride from one borough of New York to another can easily cost $20 or more. It’s common for visitors to take taxis from the airport to their hotels but then to take mass transit or walk to places such as Central Park, Ground Zero, and Wall Street. It’s not that the marginal utility of another taxi ride is 0, but the fare exceeds their willingness to pay for a second ride. When demand is elastic, consumers are on a thin margin between buying more and not buying more. Minor temperature fluctuations or a bit of rain can make the critical difference in the marginal utility of a taxi ride, and available taxis become a rarity in extreme weather. When New York City taxi fares increased by 25 percent in 2004, riders spoke of switching to public transportation for borderline situations, such as nonemergency doctor visits and dinners with married ex-

In contrast, the New York Times faces a relatively inelastic demand. The steep drop-

THE DEMAND FOR HEART SURGERY AND SIN

Talk-

The demand for lifesaving surgery is inelastic because it is a necessity. Addiction can create a perceived necessity for drugs. Without discounting the deadly repercussions of illegal drug use, economists, including Nobel laureate Milton Friedman, have used the concepts of supply and demand to argue for drug control via legalization. The legalization of drugs would increase the supply and cause the price to fall, but if the demand curve for drugs were vertical at the quantity users needed for their fixes, the quantity consumed would not change as prices changed. Lower prices would reduce profits for drug sellers and cut back on sellers’ incentives to get people hooked on their products with free samples and other aggressive marketing techniques. This could result in fewer people becoming addicted while allowing taxation and more effective regulation. Similar arguments have been made for the legalization of prostitution, as has occurred in Germany, Sweden, and most of Nevada. Opponents argue that legalization can increase the demand by attracting consumers who don’t currently use drugs or prostitutes out of respect for the law. Whichever side is right, the demand curve is at the crux of the issue.

The debates about legalizing drugs and prostitution are among many policy controversies that revolve around demand. Suppose we want to reduce drinking or smoking by imposing so-

The price elasticity of demand is critical to the pricing decisions of firms. If demand is inelastic, more revenue is gained by raising prices because the quantity demanded decreases proportionately less than the price increase. Suppose a baker selling 100 loaves of bread per day for $1 per loaf could double her prices and lose only one-

If demand is elastic, a higher price will result in lower revenues because demand decreases proportionately more than the price increase. In this case profits might increase or decrease, depending on whether the reduction in costs (thanks to decreased production) is larger or smaller than the reduction in revenues. For example, an increase in the price of pizza that decreased revenues by $1,000 but, because fewer pizzas were made, decreased costs by $1,200 would provide a net increase in profits of $200. In Part 7 (Chapter 13 and Chapter 14), we’ll see how the relatively inelastic demand that monopolies face allows them to charge higher prices and results in lower quantities than would be produced in competitive markets.

CONCLUSION

Your study of the underpinnings of demand will help you determine what shifts and shapes demand curves. Given the imminent relevance of this knowledge to you as a future policymaker, businessperson, or economics test taker, let’s review it. Diminishing marginal utility is the reason for the negative slope of the demand curve. As you get more of something, you generally receive less utility from the last unit received, and you are, therefore, willing to pay less for additional units, as indicated by the decreasing height of your individual demand curve. Because the market demand curve is the sum of all the individual demand curves, its shape, too, is dictated by diminishing marginal utility.

The price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to price. Formally, price elasticity is the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price. The sharp drop-

DISCUSSION STARTERS

How would you characterize the demand for illegal drugs among your friends? Is that demand (or lack thereof) determined by the fact that the drugs are illegal? What implications does this have for the government’s drug enforcement policy?

What are some other examples of goods with relatively high and relatively low price elasticity of demand?

Summarize in your own words the links among diminishing marginal utility, demand, and elasticity.

Explain whether you would expect the demand for the following goods to be elastic or inelastic and why: software programs, cameras, notebook paper, peaches, textbooks, Thanksgiving turkeys, all carbonated beverages, A & W root beer.