The Natural Rate of Unemployment

Fast economic growth tends to reduce the unemployment rate. So how low can the unemployment rate go? You might be tempted to say zero, but that isn’t feasible. Over the past half century, the national unemployment rate has never dropped below 2.9%.

Can there be unemployment even when many businesses are having a hard time finding workers? To answer this question, we need to examine the nature of labor markets and why they normally lead to substantial measured unemployment even when jobs are plentiful. Our starting point is the observation that, even in the best of times, jobs are constantly being created and destroyed.

Job Creation and Job Destruction

In early 2010 the unemployment rate hovered close to 10%. Even during good times, most Americans know someone who has lost his or her job. The U.S. unemployment rate in July 2007 was only 4.7%, relatively low by historical standards, yet in that month there were 4.5 million “job separations”—terminations of employment that occurred because a worker was either fired or quit voluntarily.

AP® Exam Tip

Be prepared to identify the type of unemployment given a specific scenario in both the multiple-

There are many reasons for such job loss. One is structural change in the economy: industries rise and fall as new technologies emerge and consumers’ tastes change. For example, employment in high-

This constant churning of the workforce is an inevitable feature of the modern economy. And this churning, in turn, is one source of frictional unemployment—one main reason that there is a considerable amount of unemployment even when jobs are abundant.

Frictional Unemployment

Workers who lose a job involuntarily due to job destruction often choose not to take the first new job offered. For example, suppose a skilled programmer, laid off because her software company’s product line was unsuccessful, sees a help-

Workers who spend time looking for employment are engaged in job search.

Frictional unemployment is unemployment due to the time workers spend in job search.

Economists say that workers who spend time looking for employment are engaged in job search. If all workers and all jobs were alike, job search wouldn’t be necessary; if information about jobs and workers were perfect, job search would be very quick. In practice, however, it’s normal for a worker who loses a job, or a young worker seeking a first job, to spend at least a few weeks searching.

Frictional unemployment is unemployment due to the time workers spend in job search. A certain amount of frictional unemployment is inevitable, for two reasons. One is the constant process of job creation and job destruction. The other is the fact that new workers are always entering the labor market. For example, in January 2014, out of 10.2 million workers counted as unemployed, 1.2 million were new entrants to the workforce and another 2.9 million were “re-

AP® Exam Tip

Frictional unemployment always exists in an economy. There are always people looking for better jobs or even their first job.

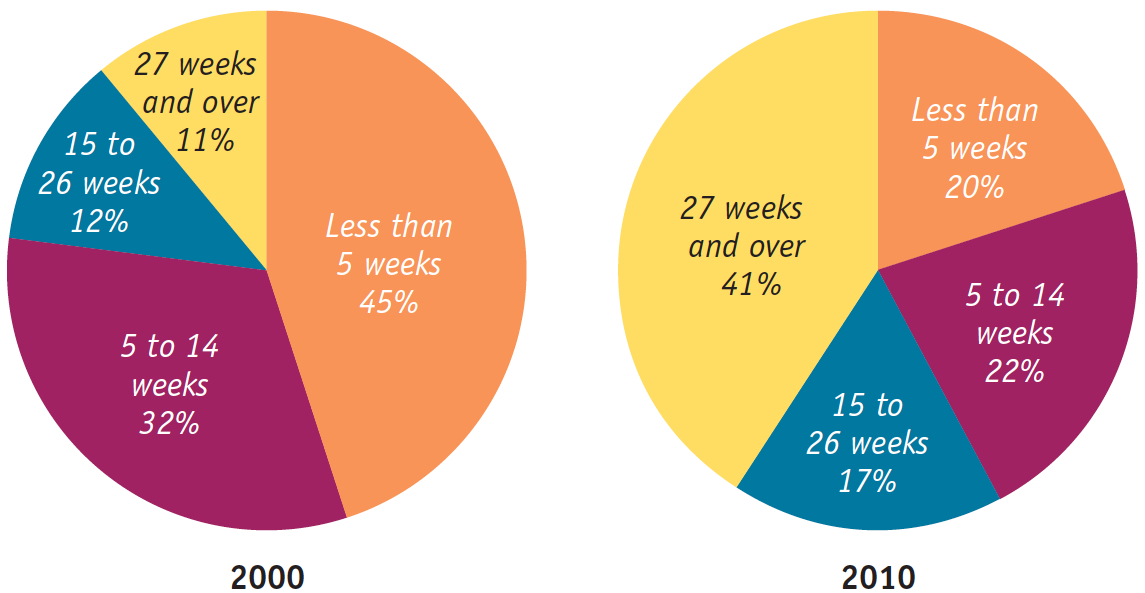

A limited amount of frictional unemployment is relatively harmless and may even be a good thing. The economy is more productive if workers take the time to find jobs that are well matched to their skills, and workers who are unemployed for a brief period while searching for the right job don’t experience great hardship. In fact, when there is a low unemployment rate, periods of unemployment tend to be quite short, suggesting that much of the unemployment is frictional. Figure 13.1 shows the composition of unemployment in 2000, when the unemployment rate was only 4%. Forty-

| Figure 13.1 | Distribution of the Unemployed by Duration of Unemployment, 2000 and 2010 |

In periods of higher unemployment, workers tend to be jobless for longer periods of time, suggesting that a smaller share of unemployment is frictional. By early 2010, when unemployment had been high for several months, for instance, the fraction of unemployed workers considered “long-

Public policy designed to help workers who lose their jobs can lead to frictional unemployment as an unintended side effect. Most economically advanced countries provide benefits to laid-

Structural Unemployment

Structural unemployment is unemployment that results when workers lack the skills required for the available jobs, or there are more people seeking jobs in a labor market than there are jobs available at the current wage rate.

Frictional unemployment exists even when the number of people seeking jobs is equal to the number of jobs being offered—

AP® Exam Tip

Structural unemployment is common in an economy. Its causes include lack of skills, automation, geographic migration, minimum wages, and insufficient product demand.

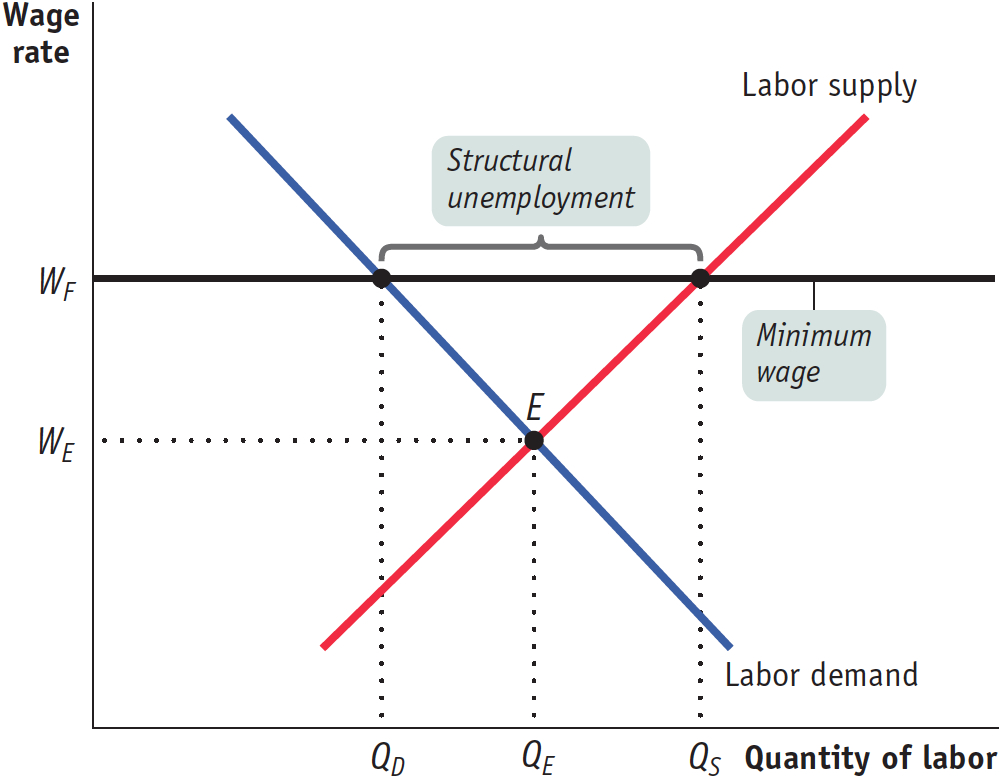

The supply and demand model tells us that the price of a good, service, or factor of production tends to move toward an equilibrium level that matches the quantity supplied with the quantity demanded. This is equally true, in general, of labor markets. Figure 13.2 shows a typical market for labor. The labor demand curve indicates that when the price of labor—

| Figure 13.2 | The Effect of a Minimum Wage on the Labor Market |

Even at the equilibrium wage rate, WE, there will still be some frictional unemployment. That’s because there will always be some workers engaged in job search even when the number of jobs available is equal to the number of workers seeking jobs. But there wouldn’t be any structural unemployment caused by a surplus of labor, as there is when the wage rate, for some reason, is persistently above WE. Several factors can lead to a wage rate in excess of WE, the most important being minimum wages, labor unions, efficiency wages, and the side effects of government policies.

Minimum Wages As explained in Module 8, a minimum wage is a government-

Figure 13.2 shows the effect of a binding minimum wage. In this market, there is a legal floor on wages, WF, which is above the equilibrium wage rate, WE. This leads to a persistent surplus in the labor market: the quantity of labor supplied, QS, is larger than the quantity demanded, QD. In other words, more people want to work than can find jobs at the minimum wage, leading to structural unemployment.

Given that minimum wages—

Although economists broadly agree that a high minimum wage has the employment-

Labor Unions The actions of labor unions can have effects similar to those of minimum wages, leading to structural unemployment. By bargaining collectively for all of a firm’s workers, unions can often win higher wages from employers than workers would have obtained by bargaining individually. This process, known as collective bargaining, is intended to tip the scales of bargaining power more toward workers and away from employers. Labor unions exercise bargaining power by threatening firms with a labor strike, a collective refusal to work. The threat of a strike can have very serious consequences for firms that have difficulty replacing striking workers. In such cases, workers acting collectively can exercise more power than they could if they acted individually.

When workers have greater bargaining power, they tend to demand and receive higher wages. Unions also bargain over benefits, such as health care and pensions, which we can think of as additional wages. Indeed, economists who study the effects of unions on wages find that unionized workers earn higher wages and more generous benefits than non-

Efficiency wages are wages that employers set above the equilibrium wage rate as an incentive for better employee performance.

Efficiency Wages Actions by firms may also contribute to structural unemployment. Firms may choose to pay efficiency wages—wages that employers set above the equilibrium wage rate as an incentive for their workers to deliver better performance.

Employers may feel the need for such incentives for several reasons. For example, employers often have difficulty directly observing how hard an employee works. They can, however, elicit more work effort by paying above-

When many firms pay efficiency wages, the result is a pool of workers who want jobs but can’t find them. So the use of efficiency wages by firms leads to structural unemployment.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment

AP® Exam Tip

The natural rate of unemployment is never zero because frictional employment always exists in an economy.

The natural rate of unemployment is the unemployment rate that arises from the effects of frictional plus structural unemployment.

Cyclical unemployment is the deviation of the actual rate of unemployment from the natural rate.

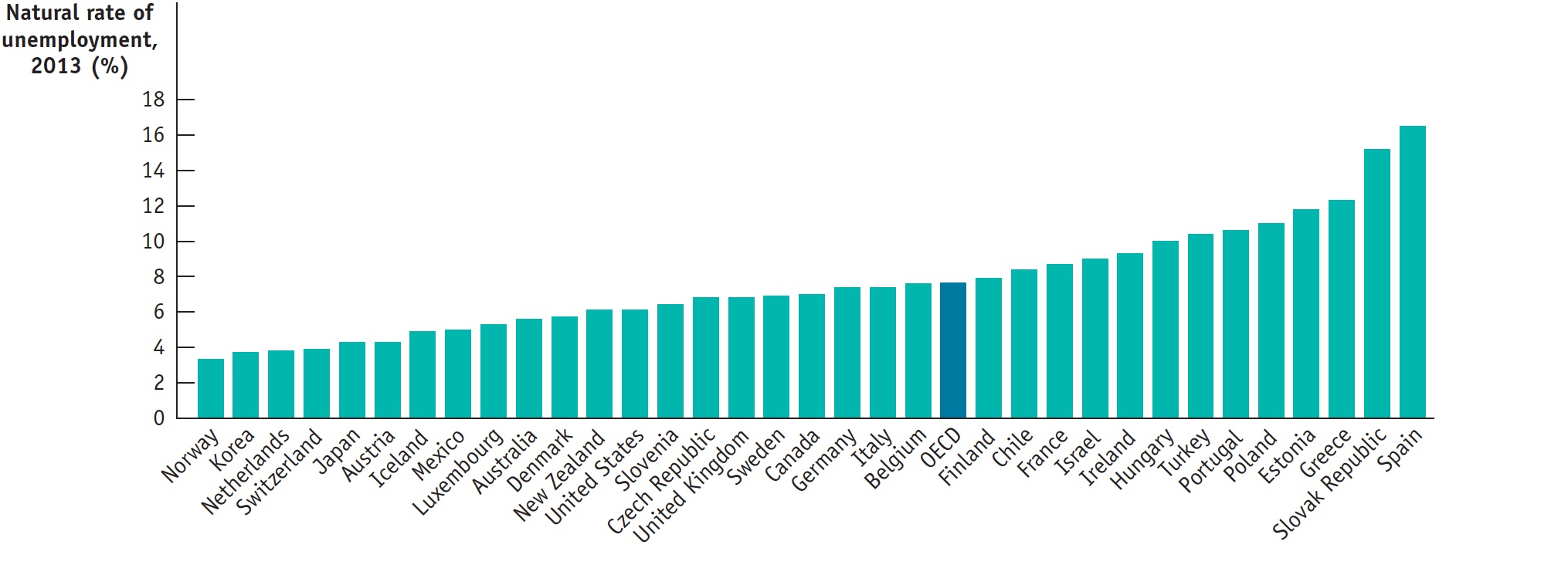

Because some frictional unemployment is inevitable and because many economies also suffer from structural unemployment, a certain amount of unemployment is normal, or “natural.” Actual unemployment fluctuates around this normal level. The natural rate of unemployment is the rate of unemployment that arises from the effects of frictional plus structural unemployment. It is the normal unemployment rate around which the actual unemployment rate fluctuates. Figure 13.3 provides estimates of the natural rates of unemployment in the 34 relatively wealthy countries that belong to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Cyclical unemployment is the deviation of the actual rate of unemployment from the natural rate; that is, it is the difference between the actual and natural rates of unemployment. As the name suggests, cyclical unemployment is the share of unemployment that arises from the business cycle. We’ll see later that public policy cannot keep the unemployment rate persistently below the natural rate without leading to accelerating inflation.

| Figure 13.3 | Natural Unemployment in OECD Countries |

We can summarize the relationships between the various types of unemployment as follows:

(13-

Frictional unemployment + Structural unemployment

(13-

Natural unemployment + Cyclical unemployment

Perhaps because of its name, people often imagine that the natural rate of unemployment is a constant that doesn’t change over time and can’t be affected by policy. Neither proposition is true. Let’s take a moment to stress two facts: the natural rate of unemployment changes over time, and it can be affected by economic policies.

Changes in the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Private-

What causes the natural rate of unemployment to change? The most important factors are changes in the characteristics of the labor force, changes in labor market institutions, and changes in government policies. Let’s look briefly at each factor.

Changes in Labor Force Characteristics In January 2014 the overall rate of unemployment in the United States was 6.6%. Young workers, however, had much higher unemployment rates: 20.7% for teenagers and 12.9% for workers aged 20 to 24. Workers aged 25 to 54 had an unemployment rate of only 6.1%.

In general, unemployment rates tend to be lower for experienced than for inexperienced workers. Because experienced workers tend to stay in a given job longer than do inexperienced ones, they have lower frictional unemployment. Also, because older workers are more likely than young workers to be family breadwinners, they have a stronger incentive to find and keep jobs.

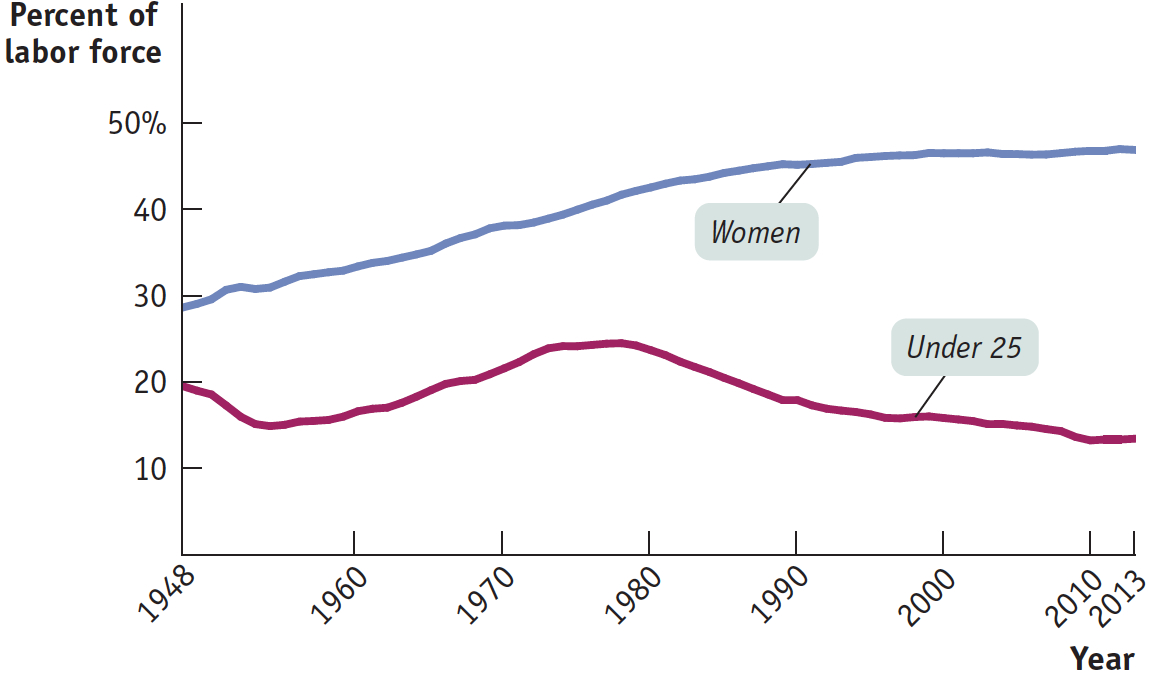

One reason the natural rate of unemployment rose during the 1970s was a large rise in the number of new workers—

| Figure 13.4 | The Changing Makeup of the U.S. Labor Force, 1948– |

Changes in Labor Market Institutions As we pointed out earlier, unions that negotiate wages above the equilibrium level can be a source of structural unemployment. Some economists believe that strong labor unions are one of the reasons for the high natural rate of unemployment in Europe. In the United States, a sharp fall in union membership after 1980 may have been one reason the natural rate of unemployment fell between the 1970s and the 1990s.

Other institutional changes may also have been at work. For example, some labor economists believe that temporary employment agencies, which have proliferated in recent years, have reduced frictional unemployment by matching workers to jobs. Furthermore, Internet websites such as monster.com may have reduced frictional unemployment by making information about job openings and job-

Technological change, coupled with labor market institutions, can also affect the natural rate of unemployment. Technological change probably leads to an increase in the demand for skilled workers who are familiar with the relevant technology and a reduction in the demand for unskilled workers. Economic theory predicts that wages should increase for skilled workers and decrease for unskilled workers. But if wages for unskilled workers cannot go down—

Changes in Government Policies A high minimum wage can cause structural unemployment. Generous unemployment benefits can increase frictional unemployment. So government policies intended to help workers can have the undesirable side effect of raising the natural rate of unemployment.

Some government policies, however, may reduce the natural rate. Two examples are job training and employment subsidies. Job-

Structural Unemployment in Eastern Germany

Structural Unemployment in Eastern Germany

In one of the most dramatic events in world history, a spontaneous popular uprising in 1989 overthrew the communist dictatorship in East Germany. Citizens quickly tore down the wall that had divided Berlin, and in short order East and West Germany became a united, democratic nation.

Then the trouble started.

After reunification, employment in East Germany plunged and the unemployment rate soared. This high unemployment rate has persisted: despite receiving massive aid from the federal German government, the economy of the former East Germany has remained persistently depressed, with an unemployment rate of 10.1% in December 2013, compared to West Germany’s unemployment rate of 6%. Other parts of formerly communist Eastern Europe have done much better. For example, the Czech Republic, which was often cited along with East Germany as a relatively successful communist economy, had a comparatively lower unemployment rate of only 7.7% in December 2013. What went wrong in East Germany?

The answer is that, through nobody’s fault, East Germany found itself suffering from severe structural unemployment. When Germany was reunified, it became clear that workers in East Germany were much less productive than their cousins in the west. Yet unions initially demanded wage rates equal to those in West Germany, and these wage rates have been slow to come down because East German workers don’t want to be treated as inferior to their West German counterparts. Meanwhile, productivity in the former East Germany has remained well below West German levels, in part because of decades of misguided investment. The result has been a persistently large mismatch between the number of workers demanded and the number of those seeking jobs.