Inflation and Deflation

In 1980 Americans were dismayed about the state of the economy for two reasons: the unemployment rate was high, and so was inflation. In fact, the high rate of inflation, not the high rate of unemployment, was the principal concern of policy makers at the time—

Why is inflation something to worry about? Why do policy makers even now get anxious when they see the inflation rate moving upward? The answer is that inflation can impose costs on the economy—

The Level of Prices Doesn’t Matter . .

The most common complaint about inflation, an increase in the price level, is that it makes everyone poorer—

An example of this kind of currency conversion happened in 2002, when France, like a number of other European countries, replaced its national currency, the franc, with the new Pan-

You could imagine doing the same thing here, replacing the dollar with a “new dollar” at a rate of exchange of, say, 7 to 1. If you owed $140,000 on your home, that would become a debt of 20,000 new dollars. If you had a wage rate of $14 an hour, it would become 2 new dollars an hour, and so on. This would bring the overall U.S. price level back to about what it was when John F. Kennedy was president.

The real wage is the wage rate divided by the price level to adjust for the effects of inflation or deflation.

Real income is income divided by the price level to adjust for the effects of inflation or deflation.

So would everyone be richer as a result because prices would be only one-

AP® Exam Tip

Inflation is an increase in the general price level that causes the real value of money to decrease. That means your dollar will buy less today than it could buy in previous years.

The moral of this story is that the level of prices doesn’t matter: the United States would be no richer than it is now if the overall level of prices was still as low as it was in 1961; conversely, the rise in prices over the past 45 years hasn’t made us poorer.

. . . But the Rate of Change of Prices Does

The conclusion that the level of prices doesn’t matter might seem to imply that the inflation rate doesn’t matter either. But that’s not true.

The inflation rate is the percentage increase in the overall level of prices per year.

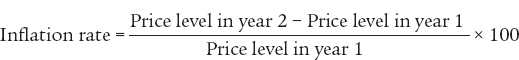

To see why, it’s crucial to distinguish between the level of prices and the inflation rate. In the next module, we will discuss precisely how the level of prices in the economy is measured using price indexes such as the consumer price index. For now, let’s look at the inflation rate, the percentage increase in the overall level of prices per year. The inflation rate is calculated as follows:

Figure 14.1 highlights the difference between the price level and the inflation rate in the United States since 1969, with the price level measured along the left vertical axis and the inflation rate measured along the right vertical axis. In the 2000s, the overall level of prices in the United States was much higher than it was in 1969—

| Figure 14.1 | The Price Level Versus the Inflation Rate, 1969– |

Economists believe that high rates of inflation impose significant economic costs. The most important of these costs are shoe-

Shoe-

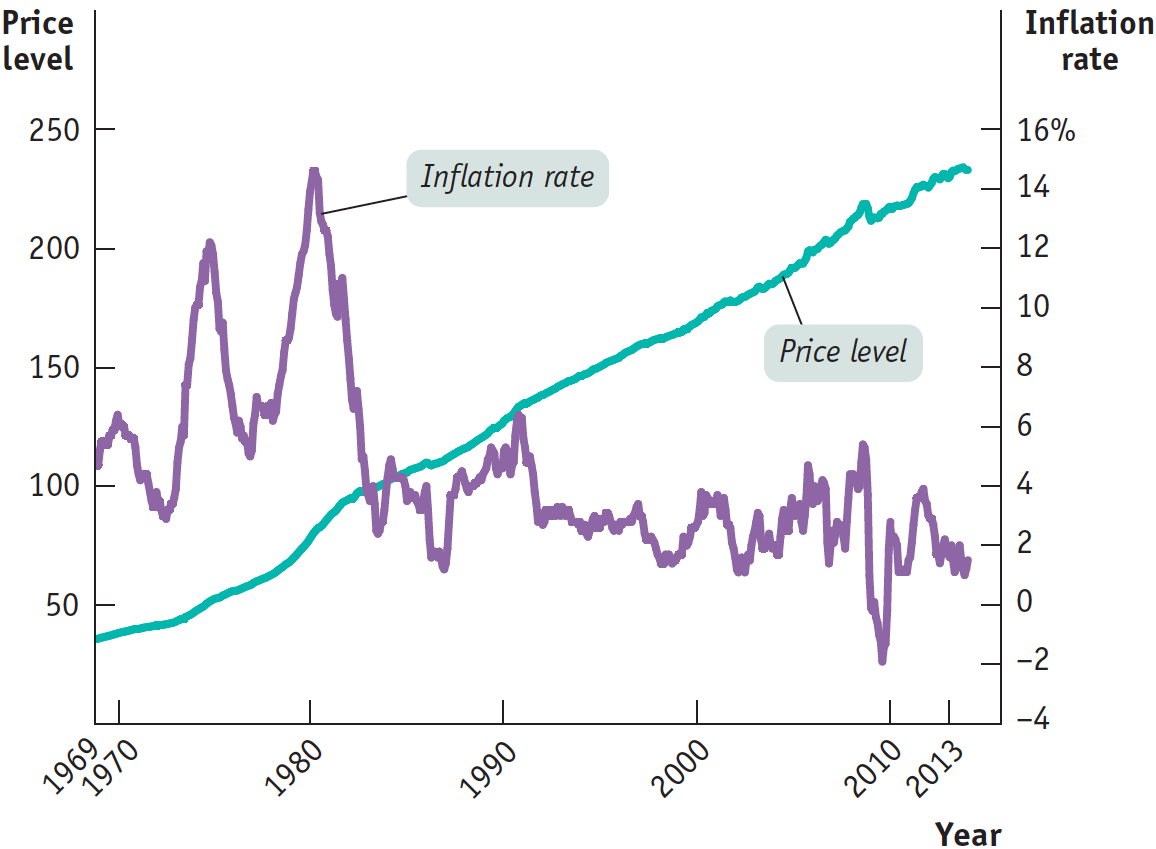

During the most famous of all inflations, the German hyperinflation of 1921–

Shoe-

Menu costs are the real costs of changing listed prices.

Increased costs of transactions caused by inflation are known as shoe-

Menu Costs In a modern economy, most of the things we buy have a listed price. There’s a price listed under each item on a supermarket shelf, a price printed on the front page of your newspaper, a price listed for each dish on a restaurant’s menu. Changing a listed price has a real cost, called a menu cost. For example, to change a price in a supermarket may require a clerk to change the price listed under the item on the shelf and an office worker to change the price associated with the item’s UPC code in the store’s computer. In the face of inflation, of course, firms are forced to change prices more often than they would if the price level was more or less stable. This means higher costs for the economy as a whole.

In times of very high inflation rates, menu costs can be substantial. During the Brazilian inflation of the early 1990s, for instance, supermarket workers reportedly spent half of their time replacing old price stickers with new ones. When the inflation rate is high, merchants may decide to stop listing prices in terms of the local currency and use either an artificial unit—

Israel’s Experience with Inflation

Israel’s Experience with Inflation

It’s hard to see the costs of inflation clearly because serious inflation is often associated with other problems that disrupt the economy and life in general, notably war or political instability (or both). In the mid-

As it happens, one of the authors spent a month visiting Tel Aviv University at the height of the inflation, so we can give a first-

First, the shoe-

Second, although menu costs weren’t that visible to a visitor, what you could see were the efforts businesses made to minimize them. For example, restaurant menus often didn’t list prices. Instead, they listed numbers that you had to multiply by another number, written on a chalkboard and changed every day, to figure out the price of a dish.

Finally, it was hard to make decisions because prices changed so much and so often. It was a common experience to walk out of a store because prices were 25% higher than at one’s usual shopping destination, only to discover that prices had just been increased 25% there, too.

Menu costs are also present in low-

Unit-

Unit-

This role of the dollar as a basis for contracts and calculation is called the unit-

Unit-

During the 1970s, when the United States had a relatively high inflation rate, the distorting effects of inflation on the tax system were a serious problem. Some businesses were discouraged from productive investment spending because they found themselves paying taxes on phantom gains. Meanwhile, some unproductive investments became attractive because they led to phantom losses that reduced tax bills. When the inflation rate fell in the 1980s—

Winners and Losers from Inflation

AP® Exam Tip

In general, borrowers are helped by inflation because it decreases the real value of what they must repay. Lenders, savers, and people with fixed incomes are hurt by inflation because it decreases the real value of the money available to them in the future.

As we’ve just learned, a high inflation rate imposes overall costs on the economy. In addition, inflation can produce winners and losers within the economy. The main reason inflation sometimes helps some people while hurting others is that economic transactions, such as loans, often involve contracts that extend over a period of time and these contracts are normally specified in nominal—

The nominal interest rate is the interest rate actually paid for a loan.

The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the rate of inflation.

The interest rate on a loan is the percentage of the loan amount that the borrower must pay to the lender, typically on an annual basis, in addition to the repayment of the loan amount itself. Economists summarize the effect of inflation on borrowers and lenders by distinguishing between nominal interest rates and real interest rates. The nominal interest rate is the interest rate that is actually paid for a loan, unadjusted for the effects of inflation. For example, the interest rates advertised on student loans and every interest rate you see listed by a bank is a nominal rate. The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate adjusted for inflation. This adjustment is achieved by simply subtracting the inflation rate from the nominal interest rate. For example, if a loan carries a nominal interest rate of 8%, but the inflation rate is 5%, the real interest rate is 8% − 5% = 3%.

When a borrower and a lender enter into a loan contract, the contract normally specifies a nominal interest rate. But each party has an expectation about the future rate of inflation and therefore an expectation about the real interest rate on the loan. If the actual inflation rate is higher than expected, borrowers gain at the expense of lenders: borrowers will repay their loans with funds that have a lower real value than had been expected—

Historically, the fact that inflation creates winners and losers has sometimes been a major source of political controversy. In 1896 William Jennings Bryan electrified the Democratic presidential convention with a speech in which he declared, “You shall not crucify mankind on a cross of gold.” What he was actually demanding was an inflationary policy. At the time, the U.S. dollar had a fixed value in terms of gold. Bryan wanted the U.S. government to abandon the gold standard and print more money, which would have raised the level of prices and, he believed, helped the nation’s farmers who were deeply in debt.

In modern America, home mortgages (loans for the purchase of homes) are the most important source of gains and losses from inflation. Americans who took out mortgages in the early 1970s quickly found their real payments reduced by higher-

Because gains for some and losses for others result from inflation that is either higher or lower than expected, yet another problem arises: uncertainty about the future inflation rate discourages people from entering into any form of long-

One last point: unexpected deflation—

Inflation Is Easy; Disinflation Is Hard

Disinflation is the process of bringing the inflation rate down.

There is not much evidence that a rise in the inflation rate from, say, 2% to 5% would do a great deal of harm to the economy. Still, policy makers generally move forcefully to bring inflation back down when it creeps above 2% or 3%. Why? Because experience shows that bringing the inflation rate down—

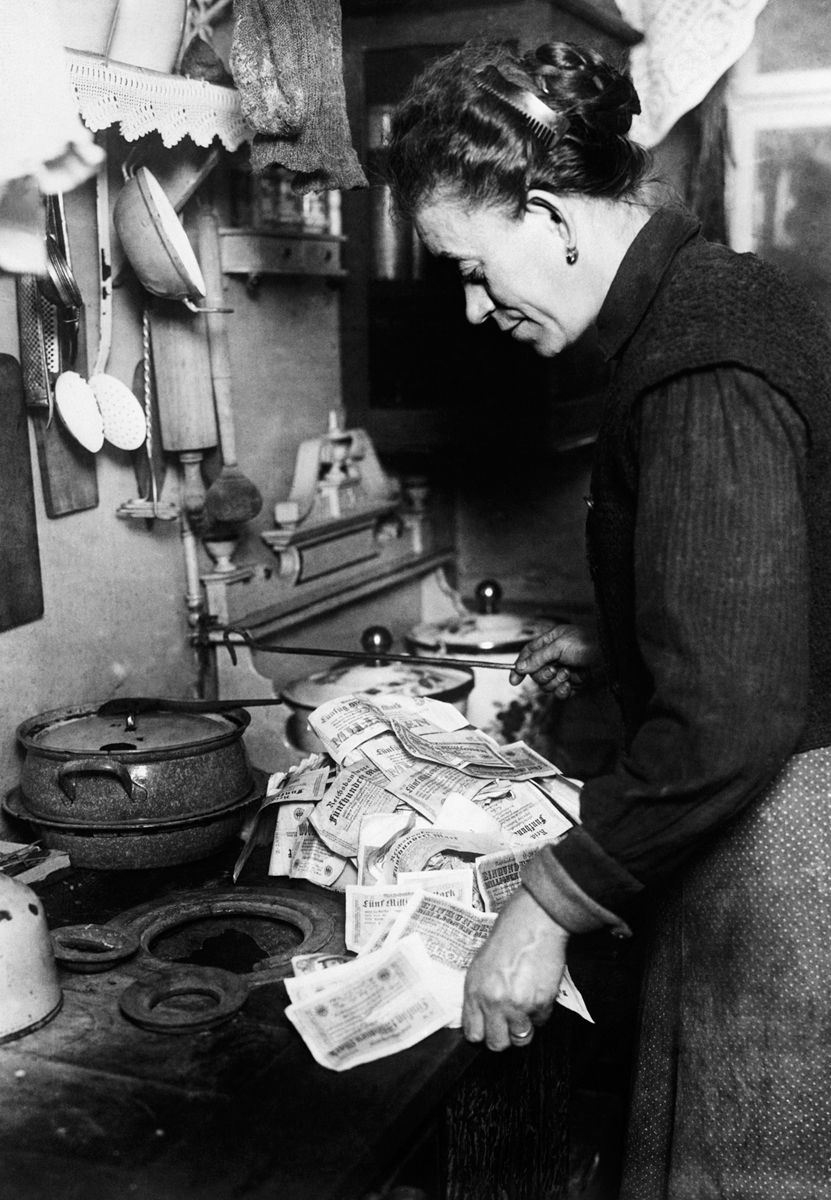

Figure 14.2 shows the inflation rate and the unemployment rate in the United States over a crucial decade, from 1978 to 1988. The decade began with an alarming rise in the inflation rate, but by the end of the period inflation averaged only about 4%. This was considered a major economic achievement—

| Figure 14.2 | The Cost of Disinflation |

Many economists believe that this period of high unemployment was necessary, because they believe that the only way to reduce inflation that has become deeply embedded in the economy is through policies that temporarily depress the economy. The best way to avoid having to put the economy through a wringer to reduce inflation, however, is to avoid having a serious inflation problem in the first place. So, policy makers respond forcefully to signs that inflation may be accelerating as a form of preventive medicine for the economy.