Consumer Spending

Should you splurge on a restaurant meal or save money by eating at home? Should you buy a new car and, if so, how expensive a model? Should you redo that bathroom or live with it for another year? In the real world, households are constantly confronted with such choices—

Current Disposable Income and Consumer Spending

The most important factor affecting a family’s consumer spending is its current disposable income—

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) collects annual data on family income and spending. Families are grouped by levels of before-

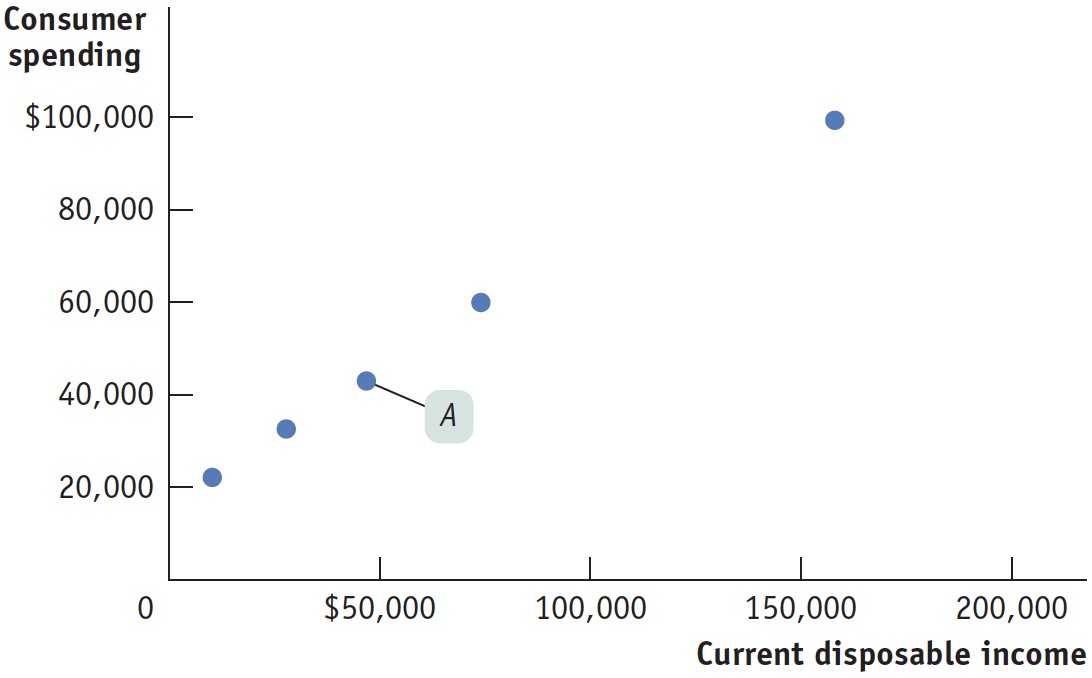

Figure 16.1 is a scatter diagram that illustrates the relationship between household current disposable income and household consumer spending for U.S. households by income group in 2012. For example, point A shows that in 2012 the middle fifth of the population had an average current disposable income of $46,777 and average spending of $43,004. The pattern of the dots slopes upward from left to right, making it clear that households with higher current disposable income had higher consumer spending.

| Figure 16.1 | Current Disposable Income and Consumer Spending for U.S. Households in 2012 |

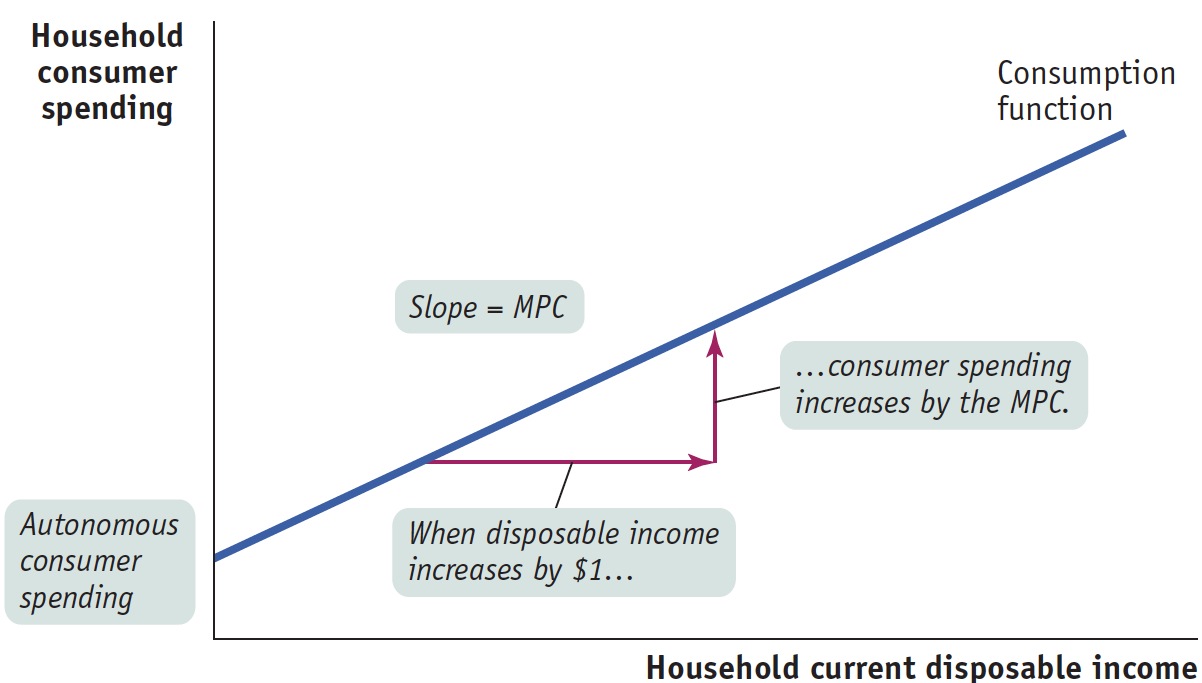

A consumption function shows how a household’s consumer spending varies with the household’s current disposable income.

A consumption function uses an equation or a graph to show how a household’s consumer spending varies with the household’s current disposable income.

Autonomous consumer spending is the amount of money a household would spend if it had no disposable income.

Figure 16.2 provides the graph of a consumption function. The vertical intercept is the household’s autonomous consumer spending: the amount the household would spend if its current disposable income were zero. Autonomous consumer spending is greater than zero because a household with no disposable income can buy some things by borrowing or using its savings.

| Figure 16.2 | The Consumption Function |

Recall that the marginal propensity to consume, or MPC, is the amount the household spends out of each additional $1 of current disposable income. The slope of any line is “rise over run”; for the consumption function, the rise is the increase in consumer spending and the run is the increase in current disposable income. For each $1 “run” in income, the “rise” is the MPC, so the slope of the consumption function is MPC/1 = MPC.

According to the data on U.S. households in Figure 16.1, the best estimate of autonomous consumption for that population in 2012 was $18,478 and the best estimate of MPC was $0.52. This implies that the marginal propensity to save (MPS)—the amount of an additional $1 of disposable income that is saved—

The aggregate consumption function is the relationship for the economy as a whole between aggregate current disposable income and aggregate consumer spending.

An individual household’s consumption function shows a microeconomic relationship between the household’s current disposable income and its spending on goods and services. Macroeconomists study the aggregate consumption function, which shows the relationship between current disposable income and consumer spending for the economy as a whole. We can represent this relationship with the following equation:

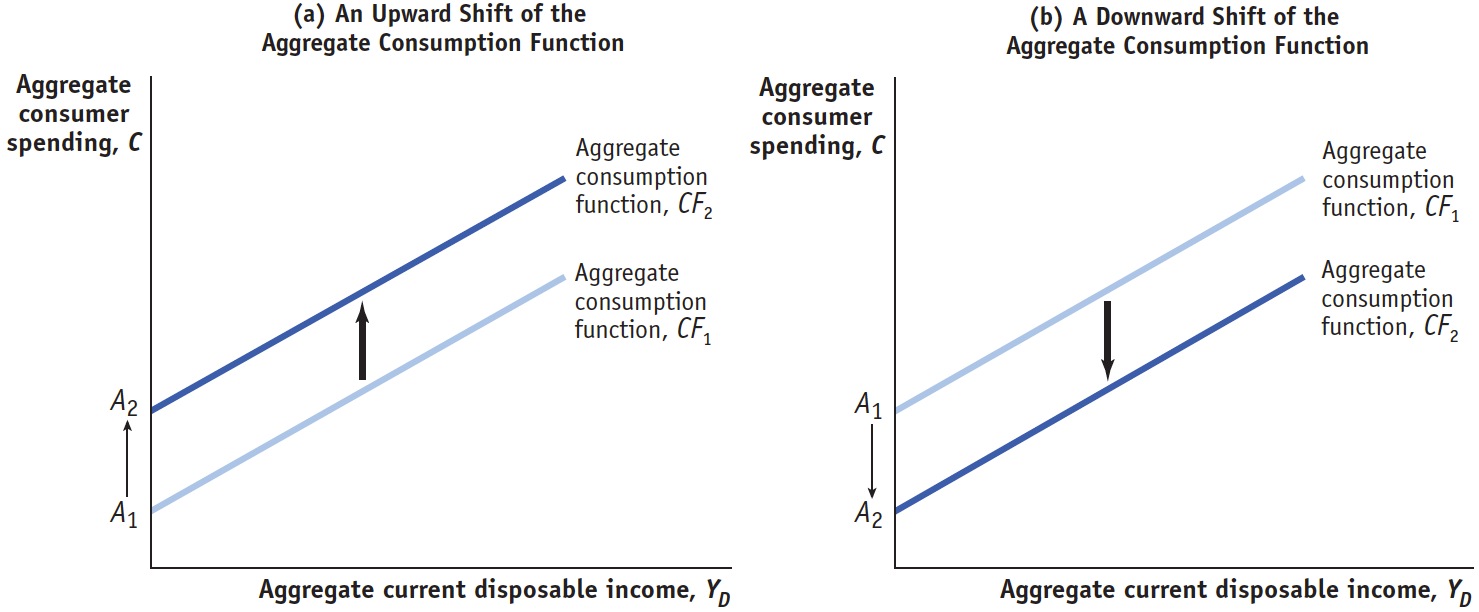

Here, C is aggregate consumer spending, YD is aggregate current disposable income, and A is aggregate autonomous consumer spending, the amount of consumer spending when disposable income is zero. Figure 16.3 shows two aggregate consumption functions as graphs, analogous to the graph of the household consumption function in Figure 16.2.

| Figure 16.3 | Shifts of the Aggregate Consumption Function |

Shifts of the Aggregate Consumption Function

The aggregate consumption function shows the relationship between current disposable income and consumer spending for the economy as a whole, other things equal. When things other than current disposable income change, the aggregate consumption function shifts. There are two principal causes of shifts of the aggregate consumption function: changes in expected future disposable income and changes in aggregate wealth.

Changes in Expected Future Disposable Income Milton Friedman argued that consumer spending ultimately depends primarily on the income people expect to have over the long term rather than on their current income. This argument is known as the permanent income hypothesis. Suppose you land a really good, well-

Conversely, suppose you have a good job but learn that the company is planning to downsize your division, raising the possibility that you may lose your job and have to take a lower-

Both of these examples show how expectations about future disposable income can affect consumer spending. The two panels of Figure 16.3, which plot aggregate current disposable income against aggregate consumer spending, show how changes in expected future disposable income affect the aggregate consumption function. In both panels, CF1 is the initial aggregate consumption function. Panel (a) shows the effect of good news: information that leads consumers to expect higher disposable income in the future than they had expected before. Consumers will now spend more at any given level of aggregate current disposable income YD, corresponding to an increase in A, aggregate autonomous consumer spending, from A1 to A2. The effect is to shift the aggregate consumption function up, from CF1 to CF2. Panel (b) shows the effect of bad news: information that leads consumers to expect lower disposable income in the future than they had expected before. Consumers will now spend less at any given level of aggregate current disposable income, YD, corresponding to a fall in A from A1 to A2. The effect is to shift the aggregate consumption function down, from CF1 to CF2.

Changes in Aggregate Wealth Imagine two individuals, Maria and Mark, both of whom expect to earn $30,000 this year. Suppose, however, that they have different histories. Maria has been working steadily for the past 10 years, owns her own home, and has $200,000 in the bank. Mark is the same age as Maria, but he has been in and out of work, hasn’t managed to buy a house, and has very little in savings. In this case, Maria has something that Mark doesn’t have: wealth. Even though they have the same disposable income, other things equal, you’d expect Maria to spend more on consumption than Mark. That is, wealth has an effect on consumer spending.

The effect of wealth on spending is emphasized by an influential economic model of how consumers make choices about spending versus saving called the life-

Because wealth affects household consumer spending, changes in wealth across the economy can shift the aggregate consumption function. A rise in aggregate wealth—