Positive Versus Normative Economics

Positive economics is the branch of economic analysis that describes the way the economy actually works.

Normative economics makes prescriptions about the way the economy should work.

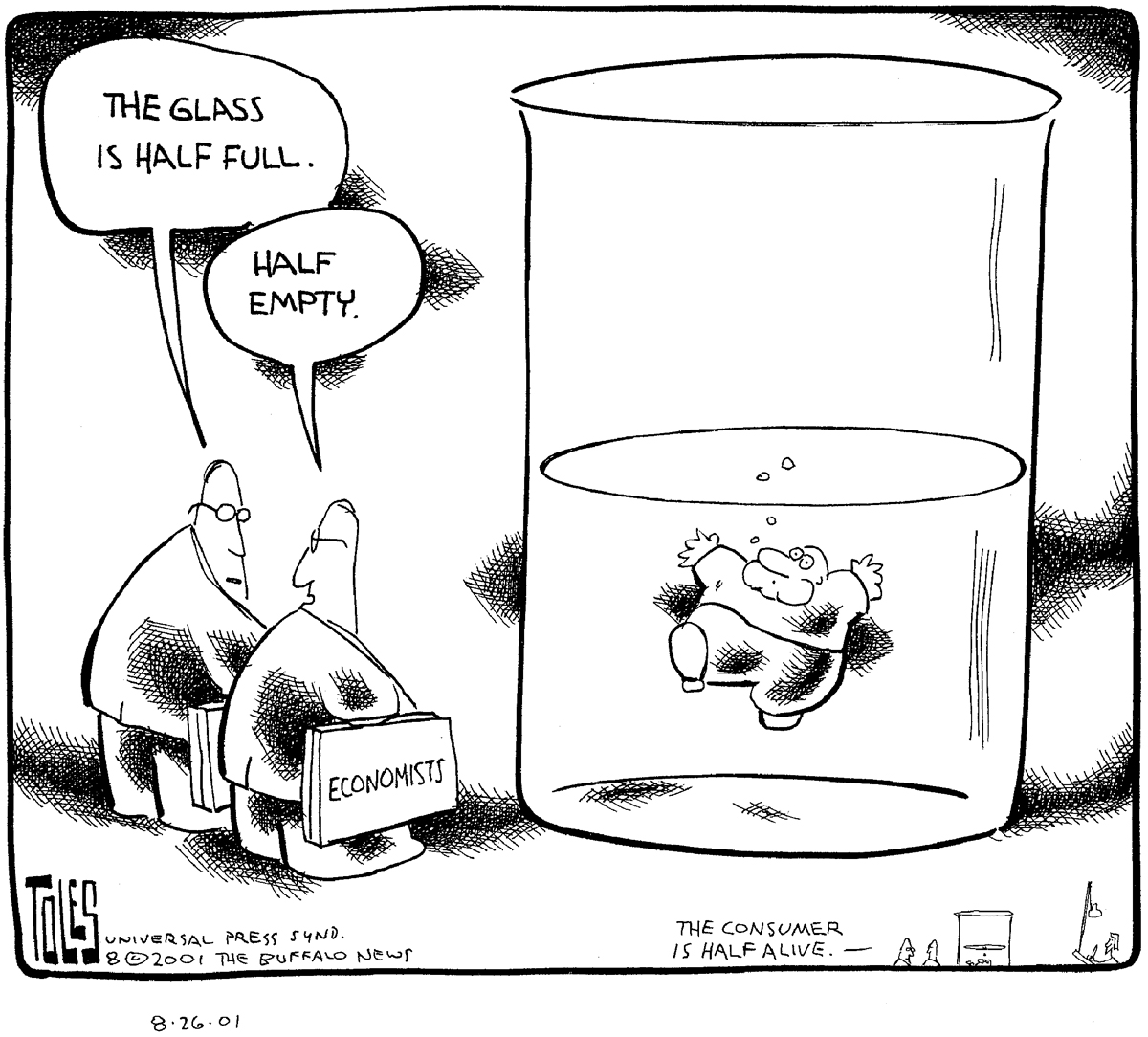

Economic analysis, as we will see throughout this book, draws on a set of basic economic principles. But how are these principles applied? That depends on the purpose of the analysis. Economic analysis that is used to answer questions about the way the economy works, questions that have definite right and wrong answers, is known as positive economics. In contrast, economic analysis that involves saying how the economy should work is known as normative economics.

Imagine that you are an economic adviser to the governor of your state and the governor is considering a change to the toll charged along the state turnpike. Below are three questions the governor might ask you.

How much revenue will the tolls yield next year?

How much would that revenue increase if the toll were raised from $1.00 to $1.50?

Should the toll be raised, bearing in mind that a toll increase would likely reduce traffic and air pollution near the road but impose some financial hardship on frequent commuters?

AP® Exam Tip

In economics, positive statements are about what is, while normative statements are about what should be.

There is a big difference between the first two questions and the third one. The first two are questions about facts. Your forecast of next year’s toll revenue without any increase will be proved right or wrong when the numbers actually come in. Your estimate of the impact of a change in the toll is a little harder to check—

But the question of whether or not tolls should be raised may not have a “right” answer—

This example highlights a key distinction between the two roles of economic analysis and presents another way to think about the distinction between positive and normative analysis: positive economics is about description, and normative economics is about prescription. Positive economics occupies most of the time and effort of economists.

Looking back at the three questions the governor might ask, it is worth noting a subtle but important difference between questions 1 and 2. Question 1 asks for a simple prediction about next year’s revenue—

The answers to such questions often serve as a guide to policy, but they are still predictions, not prescriptions. That is, they tell you what will happen if a policy is changed, but they don’t tell you whether or not that result is good. Suppose that your economic model tells you that the governor’s proposed increase in highway tolls will raise property values in communities near the road but will tax or inconvenience people who currently use the turnpike to get to work. Does that information make this proposed toll increase a good idea or a bad one? It depends on whom you ask. As we’ve just seen, someone who is very concerned with the communities near the road will support the increase, but someone who is very concerned with the welfare of drivers will feel differently. That’s a value judgment—

Still, economists often do engage in normative economics and give policy advice. How can they do this when there may be no “right” answer? One answer is that economists are also citizens, and we all have our opinions. But economic analysis can often be used to show that some policies are clearly better than others, regardless of individual opinions.

Suppose that policies A and B achieve the same goal, but policy A makes everyone better off than policy B—

For example, two different policies have been used to help low-

When policies can be clearly ranked in this way, then economists generally agree. But it is no secret that economists sometimes disagree.

When and Why Economists Disagree

Economists have a reputation for arguing with each other. Where does this reputation come from? One important answer is that media coverage tends to exaggerate the real differences in views among economists. If nearly all economists agree on an issue—

It is also worth remembering that economics, unavoidably, is often tied up in politics. On a number of issues, powerful interest groups know what opinions they want to hear. Therefore, they have an incentive to find and promote economists who profess those opinions, which gives these economists a prominence and visibility out of proportion to their support among their colleagues.

Although the appearance of disagreement among economists exceeds the reality, it remains true that economists often do disagree about important things. For example, some highly respected economists argue vehemently that the U.S. government should replace the income tax with a value-

One important source of differences is in values: as in any diverse group of individuals, reasonable people can differ. In comparison to an income tax, a value-

A second important source of differences arises from the way economists conduct economic analysis. Economists base their conclusions on models formed by making simplifying assumptions about reality. Two economists can legitimately disagree about which simplifications are appropriate—

When Economists Agree

When Economists Agree

“If all the economists in the world were laid end to end, they still couldn’t reach a conclusion.” So goes one popular economist joke. But do economists really disagree that much?

Not according to a classic survey of members of the American Economic Association, reported in the May 1992 issue of the American Economic Review. The authors asked respondents to agree or disagree with a number of statements about the economy; what they found was a high level of agreement among professional economists on many of the statements. At the top of the list, with more than 90% of the economists agreeing, were the statements “Tariffs and import quotas usually reduce general economic welfare” and “A ceiling on rents reduces the quantity and quality of housing available.” What’s striking about these two statements is that many noneconomists disagree: tariffs and import quotas to keep out foreign-

So is the stereotype of quarreling economists a myth? Not entirely. Economists do disagree quite a lot on some issues, especially in macroeconomics, but they also find a great deal of common ground.

Suppose that the U.S. government was considering a value-

Most such disputes are eventually resolved by the accumulation of evidence that shows which of the various simplifying assumptions made by economists does a better job of fitting the facts. However, in economics, as in any science, it can take a long time before research settles important disputes—