Macroeconomic Policy

Stabilization policy is the use of government policy to reduce the severity of recessions and rein in excessively strong expansions.

We’ve just seen that the economy is self-

This belief is the background to one of the most famous quotations in economics: John Maynard Keynes’s declaration, “In the long run we are all dead.” Economists usually interpret Keynes as having recommended that governments not wait for the economy to correct itself. Instead, it is argued by many economists, but not all, that the government should use fiscal policy to get the economy back to potential output in the aftermath of a shift of the aggregate demand curve. This is the rationale for active stabilization policy, which is the use of government policy to reduce the severity of recessions and rein in excessively strong expansions.

Can stabilization policy improve the economy’s performance? As we saw in Figure 18.4, the answer certainly appears to be yes. Under active stabilization policy, the U.S. economy returned to potential output in 1996 after an approximately five-

Policy in the Face of Demand Shocks

Imagine that the economy experiences a negative demand shock, like the one shown by the shift from AD1 to AD2 in Figure 19.5. Monetary and fiscal policy shift the aggregate demand curve. If policy makers react quickly to the fall in aggregate demand, they can use monetary or fiscal policy to shift the aggregate demand curve back to the right. And if policy were able to perfectly anticipate shifts of the aggregate demand curve and counteract them, it could short-

Why might a policy that short-

Does this mean that policy makers should always act to offset declines in aggregate demand? Not necessarily. As we’ll see, some policy measures to increase aggregate demand, especially those that increase budget deficits, may have long-

Should policy makers also try to offset positive shocks to aggregate demand? It may not seem obvious that they should. After all, even though inflation may be a bad thing, isn’t more output and lower unemployment a good thing? Again, not necessarily. Most economists now believe that any short-

Responding to Supply Shocks

In panel (a) of Figure 19.3, we showed the effects of a negative supply shock: in the short run such a shock leads to lower aggregate output but a higher aggregate price level. As we’ve noted, policy makers can respond to a negative demand shock by using monetary and fiscal policy to return aggregate demand to its original level. But what can or should they do about a negative supply shock?

In contrast to the case of a demand shock, there are no easy remedies for a supply shock. That is, there are no government policies that can easily counteract the changes in production costs that shift the short-

In addition, if you consider using monetary or fiscal policy to shift the aggregate demand curve in response to a supply shock, the right response isn’t obvious. Two bad things are happening simultaneously: a fall in aggregate output, leading to a rise in unemployment, and a rise in the aggregate price level. Any policy that shifts the aggregate demand curve alleviates one problem only by making the other problem worse. If the government acts to increase aggregate demand and limit the rise in unemployment, it reduces the decline in output but causes even more inflation. If it acts to reduce aggregate demand, it curbs inflation but causes a further rise in unemployment.

Is Stabilization Policy Stabilizing?

Is Stabilization Policy Stabilizing?

We’ve described the theoretical rationale for stabilization policy as a way of responding to demand shocks. But does stabilization policy actually stabilize the economy? One way we might try to answer this question is to look at the long-

So here’s the question: has the economy actually become more stable since the government began trying to stabilize it? The answer is a qualified yes. It’s qualified because data from the pre–

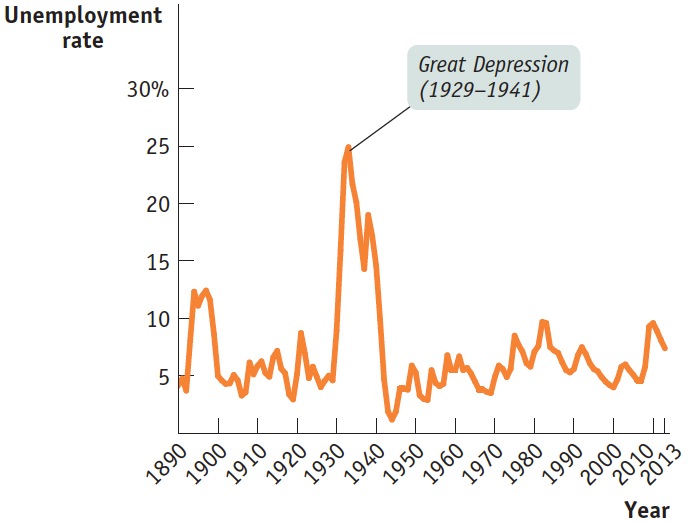

The figure on the right shows the number of unemployed as a percentage of the nonfarm labor force since 1890. (We focus on nonfarm workers because farmers, though they often suffer economic hardship, are rarely reported as unemployed.) Even ignoring the huge spike in unemployment during the Great Depression, unemployment seems to have varied a lot more before World War II than after. It’s also worth noticing that the peaks in postwar unemployment in 1975 and 1982 corresponded to major supply shocks—

It’s possible that the greater stability of the economy reflects good luck rather than policy. But on the face of it, the evidence suggests that stabilization policy is indeed stabilizing.

Source: C. Romer, “Spurious Volatility in Historical Unemployment Data,” Journal of Political Economy 94, no. 1 (1986): 1–

It’s a trade-