The Meaning of Money

AP® Exam Tip

You’ll need to know the functions and characteristics of money for the AP® exam.

In everyday conversation, people often use the word money to mean “wealth.” If you ask, “How much money does Bill Gates have?” the answer will be something like, “Oh, $50 billion or so, but who’s counting?” That is, the number will include the value of the stocks, bonds, real estate, and other assets he owns.

But the economist’s definition of money doesn’t include all forms of wealth. The dollar bills in your wallet are money; other forms of wealth—

What Is Money?

Money is any asset that can easily be used to purchase goods and services.

Money is defined in terms of what it does: money is any asset that can easily be used to purchase goods and services. For ease of use, money must be widely accepted by sellers. It is also desirable for money to be durable, portable, uniform, in limited supply, and divisible into smaller units, as with dollars and cents. In Module 22 we defined an asset as liquid if it can easily be converted into cash. Money consists of cash itself, which is liquid by definition, as well as other assets that are highly liquid.

You can see the distinction between money and other assets by asking yourself how you pay for groceries. The person at the cash register will accept dollar bills in return for milk and frozen pizza—

Currency in circulation is cash held by the public.

Checkable bank deposits are bank accounts on which people can write checks.

The money supply is the total value of financial assets in the economy that are considered money.

Of course, many stores allow you to write a check on your bank account in payment for goods (or to pay with a debit card that is linked to your bank account). Does that make your bank account money, even if you haven’t converted it into cash? Yes. Currency in circulation—actual cash in the hands of the public—

Are currency and checkable bank deposits the only assets that are considered money? It depends. As we’ll see later, there are two widely used definitions of the money supply, the total value of financial assets in the economy that are considered money. The narrower definition considers only the most liquid assets to be money: currency in circulation, traveler’s checks, and checkable bank deposits. The broader definition includes these three categories plus other assets that are “almost” checkable, such as savings account deposits that can be transferred into a checking account online with a few mouse clicks. Both definitions of the money supply, however, make a distinction between those assets that can easily be used to purchase goods and services, and those that can’t.

Money plays a crucial role in generating gains from trade because it makes indirect exchange possible. Think of what happens when a cardiac surgeon buys a new refrigerator. The surgeon has valuable services to offer—

Because the ability to make transactions with money rather than relying on bartering makes it easier to achieve gains from trade, the existence of money increases welfare, even though money does not directly produce anything. As Adam Smith put it, money “may very properly be compared to a highway, which, while it circulates and carries to market all the grass and corn of the country, produces itself not a single pile of either.”

Let’s take a closer look at the roles money plays in the economy.

Roles of Money

Money plays three main roles in any modern economy: it is a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account.

A medium of exchange is an asset that individuals acquire for the purpose of trading for goods and services rather than for their own consumption.

Medium of Exchange Our cardiac surgeon/appliance store owner example illustrates the role of money as a medium of exchange—an asset that individuals use to trade for goods and services rather than for consumption. People can’t eat dollar bills; rather, they use dollar bills to trade for food among other goods and services.

In normal times, the official money of a given country—

A store of value is a means of holding purchasing power over time.

Store of Value In order to act as a medium of exchange, money must also be a store of value—a means of holding purchasing power over time. To see why this is necessary, imagine trying to operate an economy in which ice cream cones were the medium of exchange. Such an economy would quickly suffer from, well, monetary meltdown: your medium of exchange would often turn into a sticky puddle before you could use it to buy something else. Of course, money is by no means the only store of value. Any asset that holds its purchasing power over time is a store of value. Examples include farmland and classic cars. So the store-

A unit of account is a measure used to set prices and make economic calculations.

Unit of Account Finally, money normally serves as the unit of account—the commonly accepted measure individuals use to set prices and make economic calculations. To understand the importance of this role, consider a historical fact: during the Middle Ages, peasants typically were required to provide landowners with goods and labor rather than money in exchange for a place to live. For example, a peasant might be required to work on the landowner’s land one day a week and also hand over one-

Types of Money

Commodity money is a good used as a medium of exchange that has intrinsic value in other uses.

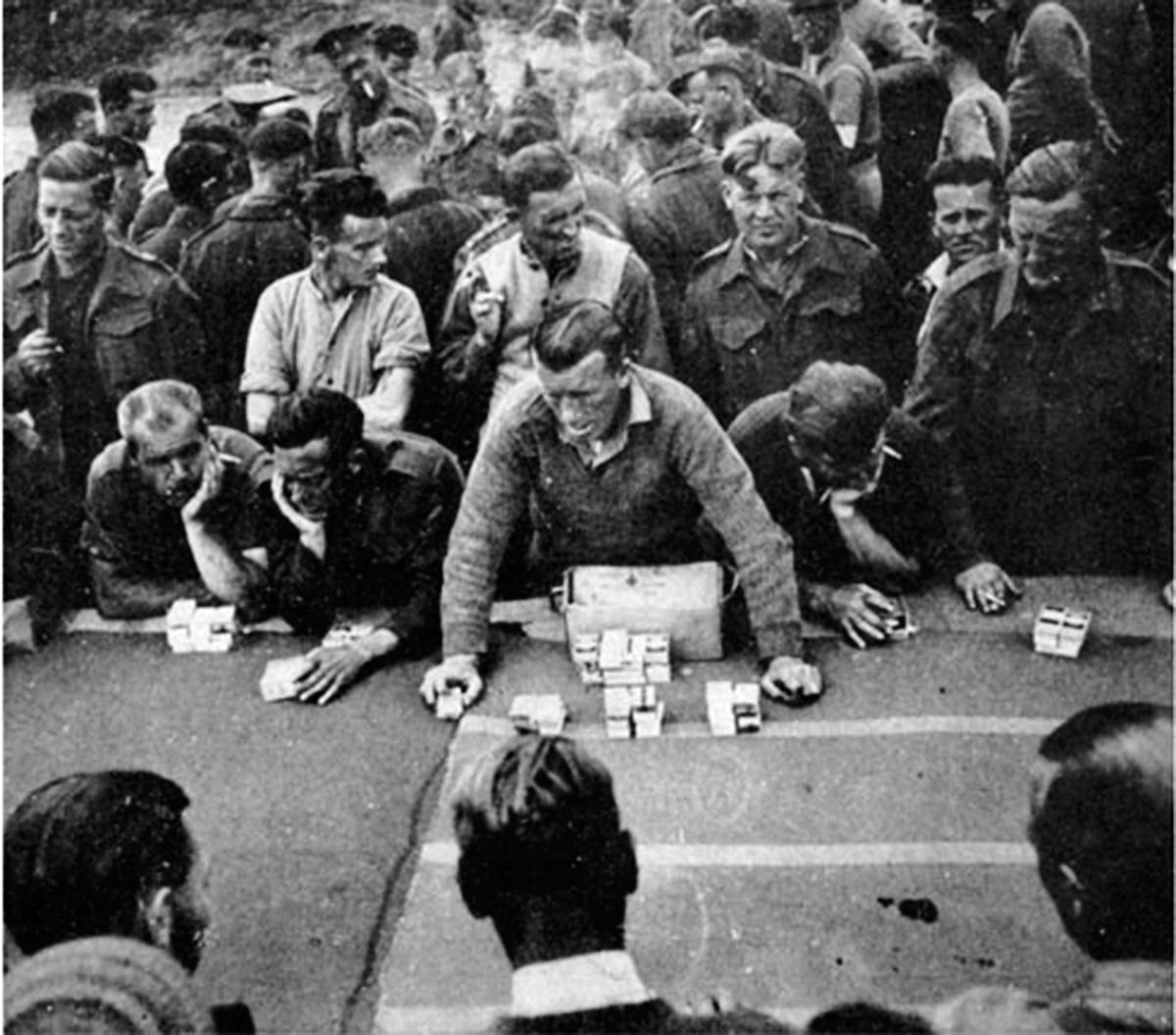

In some form or another, money has been in use for thousands of years. For most of that period, people used commodity money: the medium of exchange was a good, normally gold or silver, that had intrinsic value in other uses. These alternative uses gave commodity money value independent of its role as a medium of exchange. For example, the cigarettes that served as money in World War II POW camps were valuable because many prisoners smoked. Gold was valuable because it was used for jewelry and ornamentation, aside from the fact that it was minted into coins.

Commodity-

By 1776, the year in which the United States declared its independence and Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, there was widespread use of paper money in addition to gold and silver coins. Unlike modern dollar bills, however, this paper money consisted of notes issued by private banks, which promised to exchange their notes for gold or silver coins on demand. So the paper currency that initially replaced commodity money was commodity-

The big advantage of commodity-

In a famous passage in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith described paper money as a “waggon-

The History of the Dollar

The History of the Dollar

U.S. dollar bills are pure fiat money: they have no intrinsic value, and they are not backed by anything that does. But American money wasn’t always like that. In the early days of European settlement, the colonies that would become the United States used commodity money, partly consisting of gold and silver coins minted in Europe. But such coins were scarce on this side of the Atlantic, so the colonists relied on a variety of other forms of commodity money. For example, settlers in Virginia used tobacco as money and settlers in the Northeast used “wampum,” a type of clamshell.

Later in American history, commodity-

A curious legacy of that time was notes issued by the Citizens’ Bank of Louisiana, based in New Orleans. They became among the most widely used bank notes in the southern states. These notes were printed in English on one side and French on the other. (At the time, many people in New Orleans, originally a colony of France, spoke French.) Thus, the $10 bill read Ten on one side and Dix, the French word for “ten,” on the other. These $10 bills became known as “dixies,” probably the source of the nickname of the U.S. South.

The U.S. government began issuing official paper money, called “greenbacks,” during the Civil War, as a way to help pay for the war. At first greenbacks had no fixed value in terms of commodities. After 1873, however, the U.S. government guaranteed the value of a dollar in terms of gold, effectively turning dollars into commodity-

In 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt broke the link between dollars and gold, his own federal budget director—

Fiat money is a medium of exchange whose value derives entirely from its official status as a means of payment.

At this point you may ask, why make any use at all of gold and silver in the monetary system, even to back paper money? In fact, today’s monetary system goes even further than the system Smith admired, having eliminated any role for gold and silver. A U.S. dollar bill isn’t commodity money, and it isn’t even commodity-

Fiat money has two major advantages over commodity-

On the other hand, fiat money poses some risks. One such risk is counterfeiting. Counterfeiters usurp a privilege of the U.S. government, which has the sole legal right to print dollar bills. And the benefit that counterfeiters get by exchanging fake bills for real goods and services comes at the expense of the U.S. federal government, which covers a small but nontrivial part of its own expenses by issuing new currency to meet a growing demand for money.

The larger risk is that government officials who have the authority to print money will be tempted to abuse the privilege by printing so much money that they create inflation.

Measuring the Money Supply

AP® Exam Tip

When you see “money supply” on the AP® exam, that usually refers to the M1 measure of the money supply.

A monetary aggregate is an overall measure of the money supply.

Near-

The Federal Reserve (an institution we’ll talk more about shortly) calculates the size of two monetary aggregates, overall measures of the money supply, which differ in how strictly money is defined. The two aggregates are known, rather cryptically, as M1 and M2. (There used to be a third aggregate named—

In January 2014, M1 was valued at $2,698.2 billion, with approximately 43% accounted for by currency in circulation, approximately 57% accounted for by checkable bank deposits, and a tiny slice accounted for by traveler’s checks. In turn, M1 made up 24% of M2, valued at $11,039.1 billion.

What’s with All the Currency?

What’s with All the Currency?

Alert readers may be a bit startled at one of the numbers in the money supply: $1,159 billion of currency in circulation in January 2014. That’s $3,652 in cash for every man, woman, and child in the United States. How many people do you know who carry $3,652 in their wallets? Not many. So where is all that cash?

Part of the answer is that it isn’t in individuals’ wallets: it’s in cash registers. Businesses as well as individuals need to hold cash.

Economists also believe that cash plays an important role in transactions that people want to keep hidden. Small businesses and the self-