The Monetary Role of Banks

More than half of M1, the narrowest definition of the money supply, consists of currency in circulation—

What Banks Do

A bank is a financial intermediary that uses bank deposits, which you will recall are liquid assets, to finance borrowers’ investments in illiquid assets such as businesses and homes. Banks can lend depositors’ money to investors and thereby create liquidity because it isn’t necessary for a bank to keep all of its deposits on hand. Except in the case of a bank run—which we’ll discuss shortly—

Bank reserves are the currency that banks hold in their vaults plus their deposits at the Federal Reserve.

However, banks can’t lend out all the funds placed in their hands by depositors because they have to satisfy any depositor who wants to withdraw his or her funds. In order to meet these demands, a bank must keep substantial quantities of liquid assets on hand. In the modern U.S. banking system, these assets take the form of either currency in the bank’s vault or deposits held in the bank’s own account at the Federal Reserve. As we’ll see shortly, the latter can be converted into currency more or less instantly. Currency in bank vaults and bank deposits held at the Federal Reserve are called bank reserves. Because bank reserves are in bank vaults and at the Federal Reserve, not held by the public, they are not part of currency in circulation.

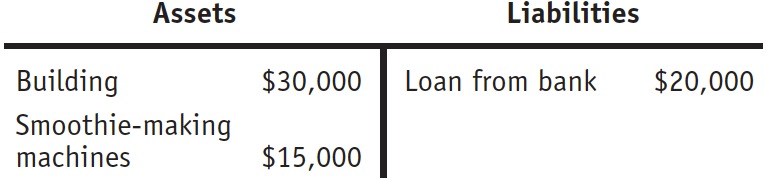

A T-

To understand the role of banks in determining the money supply, we start by introducing a simple tool for analyzing a bank’s financial position: a T-

| Figure 25.1 | A T- |

AP® Exam Tip

Make sure you understand T-

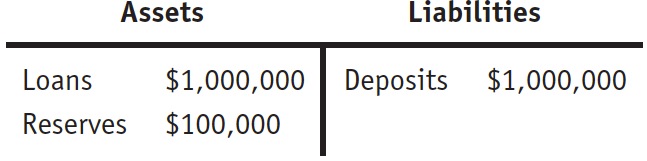

Samantha’s Smoothies is an ordinary, nonbank business. Now let’s look at the T-

Figure 25.2 shows First Street’s financial position. The loans First Street has made are on the left side because they’re assets: they represent funds that those who have borrowed from the bank are expected to repay. The bank’s only other assets, in this simplified example, are its reserves, which, as we’ve learned, can take the form of either cash in the bank’s vault or deposits at the Federal Reserve. On the right side we show the bank’s liabilities, which in this example consist entirely of deposits made by customers at First Street. These are liabilities because they represent funds that must ultimately be repaid to depositors. Notice, by the way, that in this example First Street’s assets are larger than its liabilities. That’s the way it’s supposed to be! In fact, as we’ll see shortly, banks are required by law to maintain assets larger than their liabilities by a specific percentage.

| Figure 25.2 | Assets and Liabilities of First Street Bank |

The reserve ratio is the fraction of bank deposits that a bank holds as reserves.

In this example, First Street Bank holds reserves equal to 10% of its customers’ bank deposits. The fraction of bank deposits that a bank holds as reserves is its reserve ratio.

The required reserve ratio is the smallest fraction of deposits that the Federal Reserve allows banks to hold.

In the modern American system, the Federal Reserve—

The Problem of Bank Runs

A bank can lend out most of the funds deposited in its care because in normal times only a small fraction of its depositors want to withdraw their funds on any given day. But what would happen if, for some reason, all or at least a large fraction of its depositors did try to withdraw their funds during a short period of time, such as a couple of days?

The answer is that the bank wouldn’t be able to raise enough cash to meet those demands. The reason is that banks convert most of their depositors’ funds into loans made to borrowers; that’s how banks earn revenue—

The upshot is that, if a significant number of First Street’s depositors suddenly decided to withdraw their funds, the bank’s efforts to raise the necessary cash quickly would force it to sell off its assets very cheaply. Inevitably, this would lead to a bank failure: the bank would be unable to pay off its depositors in full.

What might start this whole process? That is, what might lead First Street’s depositors to rush to pull their money out? A plausible answer is a spreading rumor that the bank is in financial trouble. Even if depositors aren’t sure the rumor is true, they are likely to play it safe and get their money out while they still can. And it gets worse: a depositor who simply thinks that other depositors are going to panic and try to get their money out will realize that this could “break the bank.” So he or she joins the rush. In other words, fear about a bank’s financial condition can be a self-

It’s a Wonderful Banking System

It’s a Wonderful Banking System

Next Christmastime, it’s a sure thing that at least one TV channel will show the 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life, featuring Jimmy Stewart as George Bailey, a small-

When the movie was made, such scenes were still fresh in Americans’ memories. There was a wave of bank runs in late 1930, a second wave in the spring of 1931, and a third wave in early 1933. By the end, more than a third of the nation’s banks had failed. To bring the panic to an end, on March 6, 1933, the newly inaugurated president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, closed all banks for a week to give bank regulators time to shut down unhealthy banks and certify healthy ones.

Since then, regulation has protected the United States and other wealthy countries against most bank runs. In fact, the scene in It’s a Wonderful Life was already out of date when the movie was made. But the last decade has seen several waves of bank runs in developing countries. For example, bank runs played a role in an economic crisis that swept Southeast Asia in 1997–

Notice that we said “most bank runs.” There are some limits on deposit insurance; in particular, currently only the first $250,000 of any bank account is insured. As a result, there can still be a rush to pull money out of a bank perceived as troubled. In fact, that’s exactly what happened to IndyMac, a Pasadena-

A bank run is a phenomenon in which many of a bank’s depositors try to withdraw their funds due to fears of a bank failure.

A bank run is a phenomenon in which many of a bank’s depositors try to withdraw their funds due to fears of a bank failure. Moreover, bank runs aren’t bad only for the bank in question and its depositors. Historically, they have often proved contagious, with a run on one bank leading to a loss of faith in other banks, causing additional bank runs. The FYI “It’s a Wonderful Banking System” describes an actual case of just such a contagion, the wave of bank runs that swept across the United States in the early 1930s. In response to that experience and similar experiences in other countries, the United States and most other modern governments have established a system of bank regulations that protects depositors and prevents most bank runs.

Bank Regulation

Should you worry about losing money in the United States due to a bank run? No. After the banking crises of the 1930s, the United States and most other countries put into place a system designed to protect depositors and the economy as a whole against bank runs. This system has three main features: deposit insurance, capital requirements, and reserve requirements. In addition, banks have access to the discount window, a source of loans from the Federal Reserve when they’re needed.

Deposit insurance guarantees that a bank’s depositors will be paid even if the bank can’t come up with the funds, up to a maximum amount per account.

Deposit Insurance Almost all banks in the United States advertise themselves as a “member of the FDIC”—the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The FDIC provides deposit insurance, a guarantee that depositors will be paid even if the bank can’t come up with the funds, up to a maximum amount per account. As this book was going to press, the FDIC guaranteed the first $250,000 of each account.

It’s important to realize that deposit insurance doesn’t just protect depositors if a bank actually fails. The insurance also eliminates the main reason for bank runs: since depositors know their funds are safe even if a bank fails, they have no incentive to rush to pull them out because of a rumor that the bank is in trouble.

Capital Requirements Deposit insurance, although it protects the banking system against bank runs, creates a well-

To reduce the incentive for excessive risk-

Reserve requirements are rules set by the Federal Reserve that determine the required reserve ratio for banks.

Reserve Requirements Another regulation used to reduce the risk of bank runs is reserve requirements, rules set by the Federal Reserve that establish the required reserve ratio for banks. For example, in the United States, the required reserve ratio for checkable bank deposits is currently between zero and 10%, depending on the amount deposited at the bank.

The discount window is the channel through which the Federal Reserve lends money to banks.

The Discount Window One final protection against bank runs is the fact that the Federal Reserve stands ready to lend money to banks through a channel known as the discount window. The ability to borrow money means a bank can avoid being forced to sell its assets at fire-