The Reserve Requirement

The federal funds market allows banks that fall short of the reserve requirement to borrow funds from banks with excess reserves.

The federal funds rate is the interest rate that banks charge other banks for loans, as determined in the federal funds market.

In our discussion of bank runs, we noted that the Fed sets a minimum required reserve ratio, currently between zero and 10% for checkable bank deposits. Banks that fail to maintain at least the required reserve ratio on average over a two-week period face penalties.

A trader works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange as the Federal Reserve announces that it will be keeping its key interest rate near zero.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

What does a bank do if it has insufficient reserves to meet the Fed’s reserve requirement? Normally, it borrows additional reserves from other banks via the federal funds market, a financial market that allows banks that fall short of the reserve requirement to borrow reserves (usually just overnight) from banks that are holding excess reserves. The interest rate in this market is determined by supply and demand, but the supply and demand for bank reserves are both strongly affected by Federal Reserve actions. Later we will see how the federal funds rate, the interest rate at which funds are borrowed and lent among banks in the federal funds market, plays a key role in modern monetary policy.

In order to alter the money supply, the Fed can change reserve requirements. If the Fed reduces the required reserve ratio, banks will lend a larger percentage of their deposits, leading to more loans and an increase in the money supply via the money multiplier. Alternatively, if the Fed increases the required reserve ratio, banks are forced to reduce their lending, leading to a fall in the money supply via the money multiplier. Under current practice, however, the Fed doesn’t use changes in reserve requirements to actively manage the money supply. The last significant change in reserve requirements was in 1992.

The Discount Rate

The discount rate is the interest rate the Fed charges on loans to banks.

Banks in need of reserves can also borrow from the Fed itself via the discount window. The discount rate is the interest rate the Fed charges on those loans. Normally, the discount rate is set 1 percentage point above the federal funds rate in order to discourage banks from turning to the Fed when they are in need of reserves.

In order to alter the money supply, the Fed can change the discount rate. Beginning in the fall of 2007, the Fed reduced the spread between the federal funds rate and the discount rate as part of its response to the ongoing financial crisis. As a result, by the spring of 2008 the discount rate was only 0.25 percentage points above the federal funds rate.

Page 263

If the Fed reduces the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate, the cost to banks of being short of reserves falls. Banks respond by increasing their lending, and the money supply increases via the money multiplier. If the Fed increases the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate, bank lending falls—and so will the money supply via the money multiplier.

The Fed normally doesn’t use the discount rate to actively manage the money supply. As we mentioned earlier, however, there was a temporary surge in lending through the discount window in 2007 in response to the financial crisis. Today, normal monetary policy is conducted almost exclusively using the Fed’s third policy tool: open-market operations.

Open-Market Operations

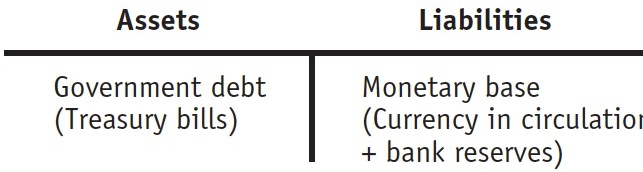

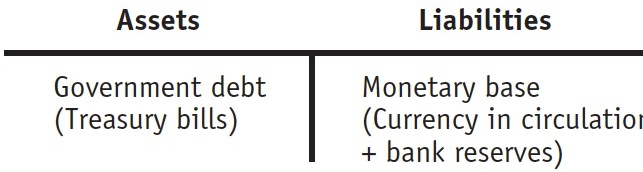

Like the banks it oversees, the Federal Reserve has assets and liabilities. The Fed’s assets consist of its holdings of debt issued by the U.S. government, mainly short-term U.S. government bonds with a maturity of less than one year, known as U.S. Treasury bills. Remember, the Fed and the U.S. government are not one entity; U.S. Treasury bills held by the Fed are a liability of the government but an asset of the Fed. The Fed’s liabilities consist of currency in circulation and bank reserves. Figure 27.1 summarizes the normal assets and liabilities of the Fed in the form of a T-account.

| Figure 27.1 | The Federal Reserve’s Assets and Liabilities |

Figure 27.1: The Federal Reserve’s Assets and LiabilitiesThe Federal Reserve holds its assets mostly in short-term government bonds called U.S. Treasury bills. Its liabilities are the monetary base—currency in circulation plus bank reserves.

An open-market operation is a purchase or sale of government debt by the Fed.

In an open-market operation, the Federal Reserve buys or sells U.S. Treasury bills, normally through a transaction with commercial banks—banks that mainly make business loans, as opposed to home loans. The Fed never buys U.S. Treasury bills directly from the federal government. There’s a good reason for this: when a central bank buys government debt directly from the government, it is lending directly to the government—in effect, the central bank is issuing “printing money” to finance the government’s budget deficit. As we’ll see later in the book, this has historically been a formula for disastrous levels of inflation.

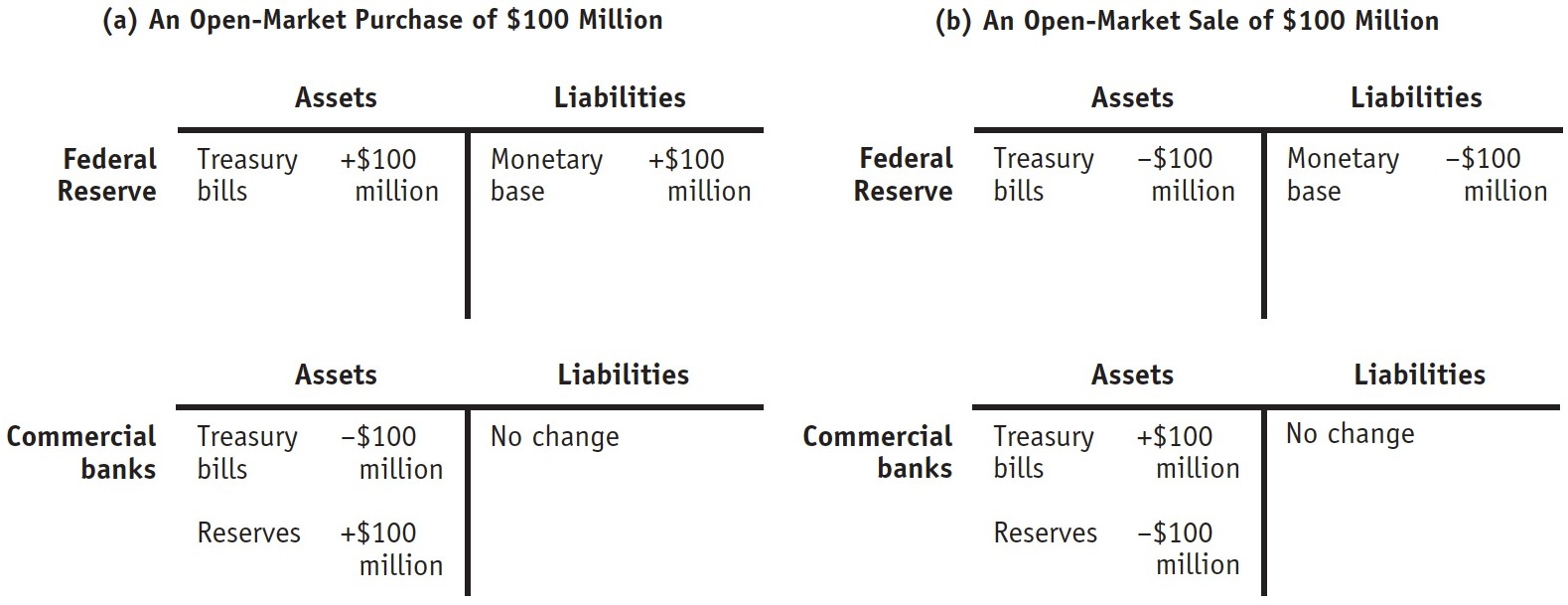

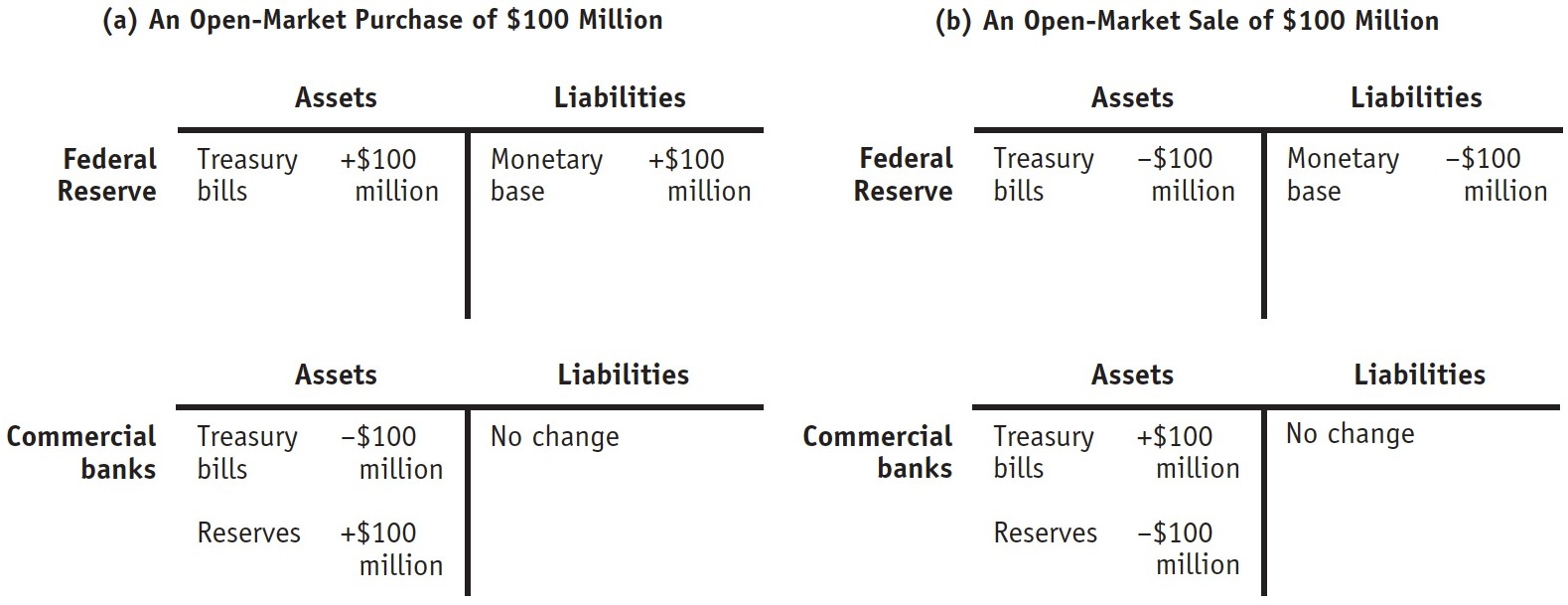

The two panels of Figure 27.2 show the changes in the financial position of both the Fed and commercial banks that result from open-market operations. When the Fed buys U.S. Treasury bills from a commercial bank, it pays by crediting the bank’s reserve account by an amount equal to the value of the Treasury bills. This is illustrated in panel (a): the Fed buys $100 million of U.S. Treasury bills from commercial banks, which increases the monetary base by $100 million because it increases bank reserves by $100 million. When the Fed sells U.S. Treasury bills to commercial banks, it debits the banks’ accounts, reducing their reserves. This is shown in panel (b), where the Fed sells $100 million of U.S. Treasury bills. Here, bank reserves and the monetary base decrease.

| Figure 27.2 | Open-Market Operations by the Federal Reserve |

Figure 27.2: Open-Market Operations by the Federal ReserveIn panel (a), the Federal Reserve increases the monetary base by purchasing U.S. Treasury bills from private commercial banks in an open-market operation. Here, a $100 million purchase of U.S. Treasury bills by the Federal Reserve is paid for by a $100 million increase in the monetary base. This will ultimately lead to an increase in the money supply via the money multiplier as banks lend out some of these new reserves. In panel (b), the Federal Reserve reduces the monetary base by selling U.S. Treasury bills to private commercial banks in an open-market operation. Here, a $100 million sale of U.S. Treasury bills leads to a $100 million reduction in commercial bank reserves, resulting in a $100 million decrease in the monetary base. This will ultimately lead to a fall in the money supply via the money multiplier as banks reduce their loans in response to a fall in their reserves.

You might wonder where the Fed gets the funds to purchase U.S. Treasury bills from banks. The answer is that it simply creates them with a stroke of the pen—or, these days, a click of the mouse—that credits the banks’ accounts with extra reserves. The Fed issues currency to pay for Treasury bills only when banks want the additional reserves in the form of currency. Remember, the modern dollar is fiat money, which isn’t backed by anything. So the Fed can add to the monetary base at its own discretion.

Page 264

The change in bank reserves caused by an open-market operation doesn’t directly affect the money supply. Instead, it starts the money multiplier in motion. After the $100 million increase in reserves shown in panel (a), commercial banks would lend out their additional reserves, immediately increasing the money supply by $100 million. Some of those loans would be deposited back into the banking system, increasing reserves again and permitting a further round of loans, and so on, leading to a rise in the money supply. An open-market sale has the reverse effect: bank reserves fall, requiring banks to reduce their loans, leading to a fall in the money supply.

Economists often say, loosely, that the Fed controls the money supply—checkable deposits plus currency in circulation. In fact, it controls only the monetary base—bank reserves plus currency in circulation. But by increasing or decreasing the monetary base, the Fed can exert a powerful influence on both the money supply and interest rates. This influence is the basis of monetary policy, discussed in detail in Modules 28 and 29.