Economic Growth

20th Century Advertising/Alamy

Economic growth is an increase in the maximum amount of goods and services an economy can produce.

In 1955 Americans were delighted with the nation’s prosperity. The economy was expanding, consumer goods that had been rationed during World War II were available for everyone to buy, and most Americans believed, rightly, that they were better off than citizens of any other nation, past or present. Yet by today’s standards Americans were quite poor in 1955. For example, in 1955 only 33% of American homes contained washing machines, and hardly anyone had air conditioning. If we turn the clock back to 1905, we find that life for most Americans was startlingly primitive by today’s standards.

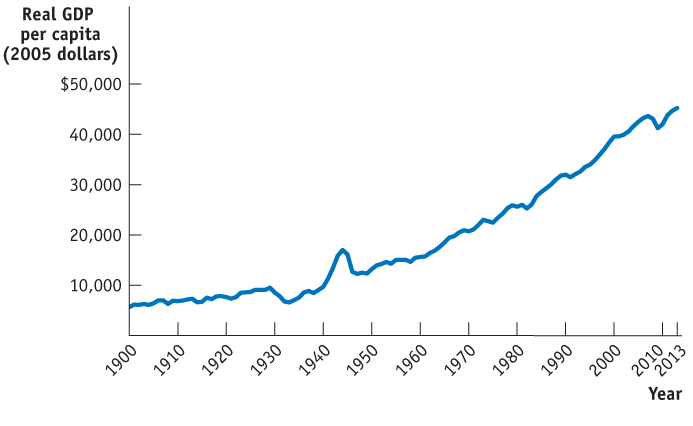

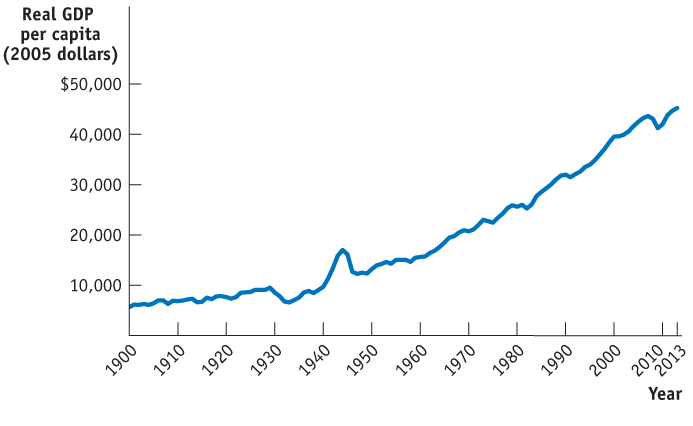

Why are the vast majority of Americans today able to afford conveniences that many lacked in 1955? The answer is economic growth, an increase in the maximum possible output of an economy. Unlike the short-term increases in aggregate output that occur as an economy recovers from a downturn in the business cycle, economic growth is an increase in productive capacity that permits a sustained rise in aggregate output over time. Figure 2.2 shows annual figures for U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita—the value of final goods and services produced in the U.S. per person—from 1900 to 2013. As a result of this economic growth, the U.S. economy’s aggregate output per person was more than eight times as large in 2013 as it was in 1900.

| Figure 2.2 | Growth, the Long View |

Figure 2.2: Growth, the Long ViewOver the long run, growth in real GDP per capita has dwarfed the ups and downs of the business cycle. Except for the recession that began the Great Depression, recessions are almost invisible.

Sources: Angus Maddison, “Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP,

1–2006 AD,” http://www.ggdc.net/maddison; Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden, “The First Update of the Maddison Project; Re-estimating Growth Before 1820;” Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Economic growth is fundamental to a nation’s prosperity. A sustained rise in output per person allows for higher wages and a rising standard of living. The need for economic growth is urgent in poorer, less developed countries, where a lack of basic necessities makes growth a central concern of economic policy.

AP® Exam Tip

Economic growth is an increase in the economy’s potential output. Changes in real GDP (output) do not necessarily indicate economic growth. Temporary fluctuations in economic conditions often alter real GDP when there has been no change in the economy’s potential output.

As you will see when studying macroeconomics, the goal of economic growth can be in conflict with the goal of hastening recovery from an economic downturn. What is good for economic growth can be bad for short-run stabilization of the business cycle, and vice versa.

We have seen that macroeconomics is concerned with the long-run trends in aggregate output as well as the short-run ups and downs of the business cycle. Now that we have a general understanding of the important topics studied in macroeconomics, we are almost ready to apply economic principles to real economic issues. To do this requires one more step—an understanding of how economists use models.

Page 14

The Use of Models in Economics

In 1901, one year after their first glider flights at Kitty Hawk, the Wright brothers built something else that would change the world—a wind tunnel. This was an apparatus that let them experiment with many different designs for wings and control surfaces. These experiments gave them knowledge that would make heavier-than-air flight possible. Needless to say, testing an airplane design in a wind tunnel is cheaper and safer than building a full-scale version and hoping it will fly. More generally, models play a crucial role in almost all scientific research—economics included.

A model is a simplified representation used to better understand a real-life situation.

A model is any simplified version of reality that is used to better understand a real-life situation. But how do we create a simplified representation of an economic situation? One possibility—an economist’s equivalent of a wind tunnel—is to find or create a real but simplified economy. For example, economists interested in the economic role of money have studied the system of exchange that developed in World War II prison camps, in which cigarettes became a universally accepted form of payment, even among prisoners who didn’t smoke.

Another possibility is to simulate the workings of the economy on a computer. For example, when changes in tax law are proposed, government officials use tax models—large mathematical computer programs—to assess how the proposed changes would affect different groups of people. Models can also be depicted by graphs and equations. Starting in the next module you will see how graphical models illustrate the relationships between variables and reveal the effects of changes in the economy.

The other things equal assumption means that all other relevant factors remain unchanged. This is also known as the ceteris paribus assumption.

Models are important because their simplicity allows economists to focus on the influence of only one change at a time. That is, they allow us to hold everything else constant and to study how one change affects the overall economic outcome. So when building economic models, an important assumption is the other things equal assumption, which means that all other relevant factors remain unchanged. Sometimes the Latin phrase ceteris paribus, which means “other things equal,” is used.

But it isn’t always possible to find or create a small-scale version of the whole economy, and a computer program is only as good as the data it uses. (Programmers have a saying: garbage in, garbage out.) For many purposes, the most effective form of economic modeling is the construction of “thought experiments”: simplified, hypothetical versions of real-life situations. And as you will see throughout this book, economists’ models are very often in the form of a graph. In the next module, we will look at the production possibilities curve, a model that helps economists think about the choices every economy faces.