The Budget Balance

AP® Exam Tip

The budget balance is the difference between the government’s tax revenue and its spending, both on goods and services and on government transfers, in a given year.

Headlines about the government’s budget tend to focus on just one point: whether the government is running a budget surplus or a budget deficit and, in either case, how big. People usually think of surpluses as good: when the federal government ran a record surplus in 2000, many people regarded it as a cause for celebration. Conversely, people usually think of deficits as bad: when the Congressional Budget Office projected a $675 billion federal deficit in 2014, many people regarded it as a cause for concern.

How do surpluses and deficits fit into the analysis of fiscal policy? Are deficits ever a good thing and surpluses ever a bad thing? To answer those questions, let’s look at the causes and consequences of surpluses and deficits.

The Budget Balance as a Measure of Fiscal Policy

What do we mean by surpluses and deficits? The budget balance, which we have previously defined, is the difference between the government’s tax revenue and its spending, both on goods and services and on government transfers, in a given year. That is, the budget balance—

(30-

where T is the value of tax revenues, G is government purchases of goods and services, and TR is the value of government transfers. A budget surplus is a positive budget balance, and a budget deficit is a negative budget balance.

AP® Exam Tip

The budget deficit almost always rises when the unemployment rate rises and falls when the unemployment rate falls.

Other things equal, expansionary fiscal policies—

You might think this means that changes in the budget balance can be used to measure fiscal policy. In fact, economists often do just that: they use changes in the budget balance as a “quick-

Two different changes in fiscal policy that have equal-

sized effects on the budget balance may have quite unequal effects on the economy. As we have already seen, changes in government purchases of goods and services have a larger effect on real GDP than equal- sized changes in taxes and government transfers. Often, changes in the budget balance are themselves the result, not the cause, of fluctuations in the economy.

To understand the second point, we need to examine the effects of the business cycle on the budget.

The Business Cycle and the Cyclically Adjusted Budget Balance

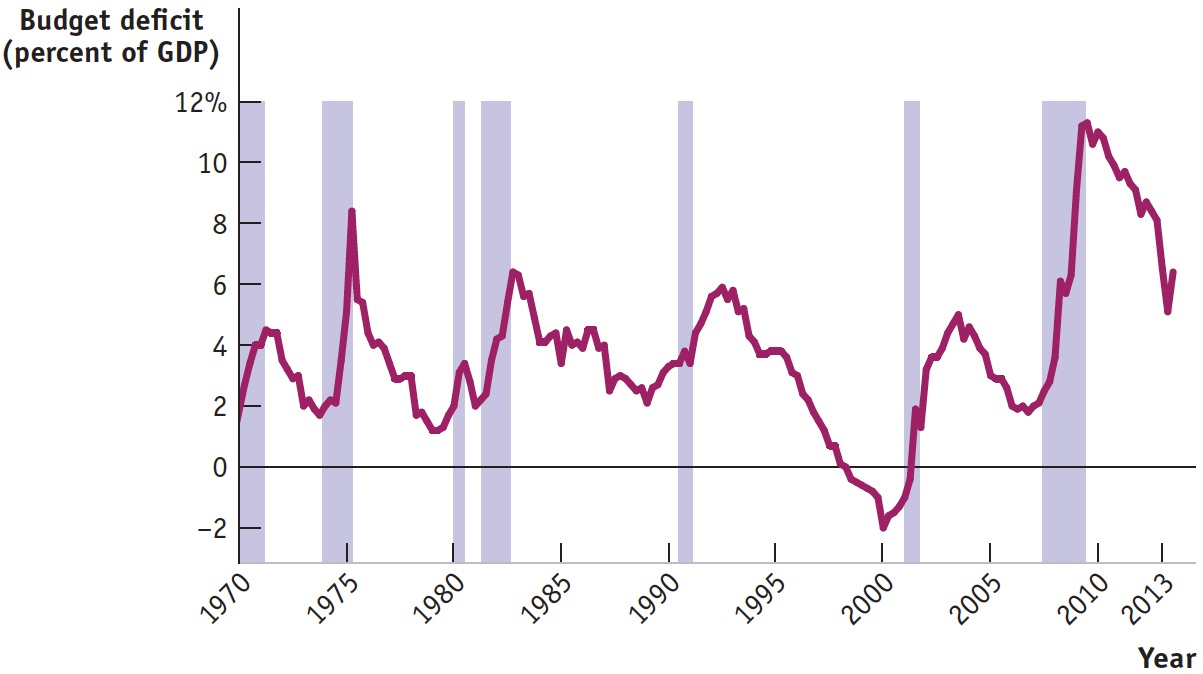

Historically, there has been a strong relationship between the federal government’s budget balance and the business cycle. The budget tends to move into deficit when the economy experiences a recession, but deficits tend to get smaller or even turn into surpluses when the economy is expanding. Figure 30.1 shows the federal budget deficit as a percentage of GDP from 1970 to 2013. Shaded areas indicate recessions; unshaded areas indicate expansions. As you can see, the federal budget deficit increased around the time of each recession and usually declined during expansions. In fact, in the late stages of the long expansion from 1991 to 2000, the deficit actually became negative—

| Figure 30.1 | The U.S. Federal Budget Deficit and the Business Cycle |

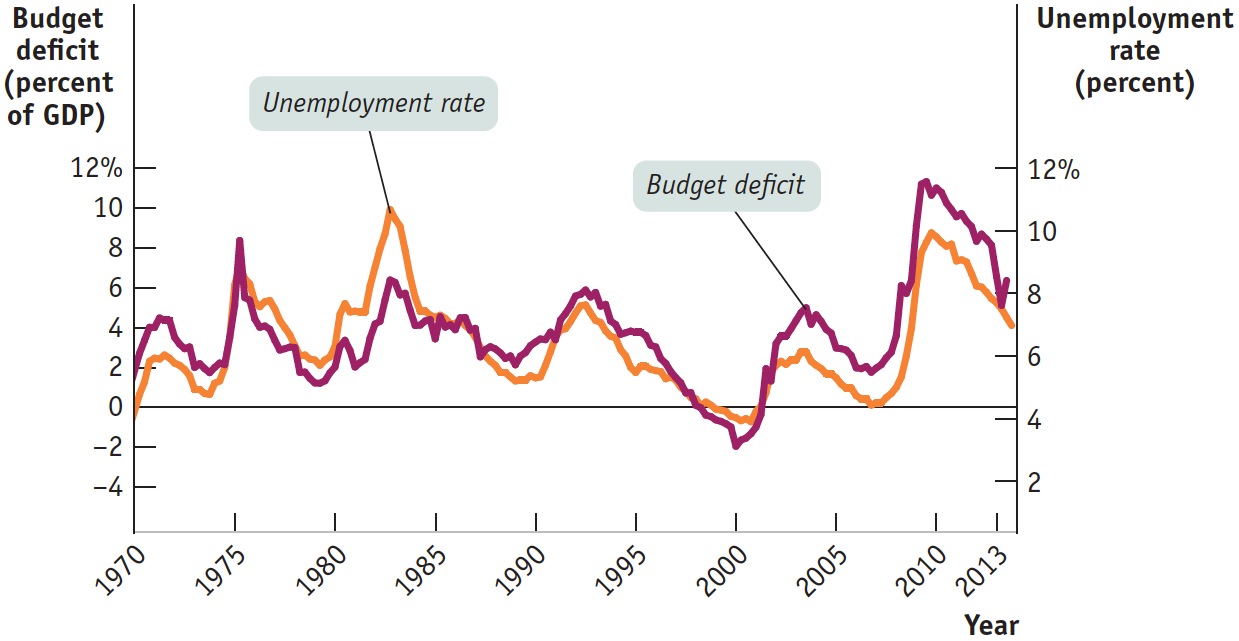

The relationship between the business cycle and the budget balance is even more clear if we compare the budget deficit as a percentage of GDP with the unemployment rate, as we do in Figure 30.2. The budget deficit almost always rises when the unemployment rate rises and falls when the unemployment rate falls.

| Figure 30.2 | The U.S. Federal Budget Deficit and the Unemployment Rate |

Is this relationship between the business cycle and the budget balance evidence that policy makers engage in discretionary fiscal policy? Not necessarily. It is largely automatic stabilizers that drive the relationship shown in Figure 30.2. As we learned in the discussion of automatic stabilizers in Module 21, government tax revenue tends to rise and some government transfers, like unemployment insurance payments, tend to fall when the economy expands. Conversely, government tax revenue tends to fall and some government transfers tend to rise when the economy contracts. So the budget tends to move toward surplus during expansions and toward deficit during recessions even without any deliberate action on the part of policy makers.

In assessing budget policy, it’s often useful to separate movements in the budget balance due to the business cycle from movements due to discretionary fiscal policy changes. The former are affected by automatic stabilizers and the latter by deliberate changes in government purchases, government transfers, or taxes. It’s important to realize that business-

The cyclically adjusted budget balance is an estimate of what the budget balance would be if real GDP were exactly equal to potential output.

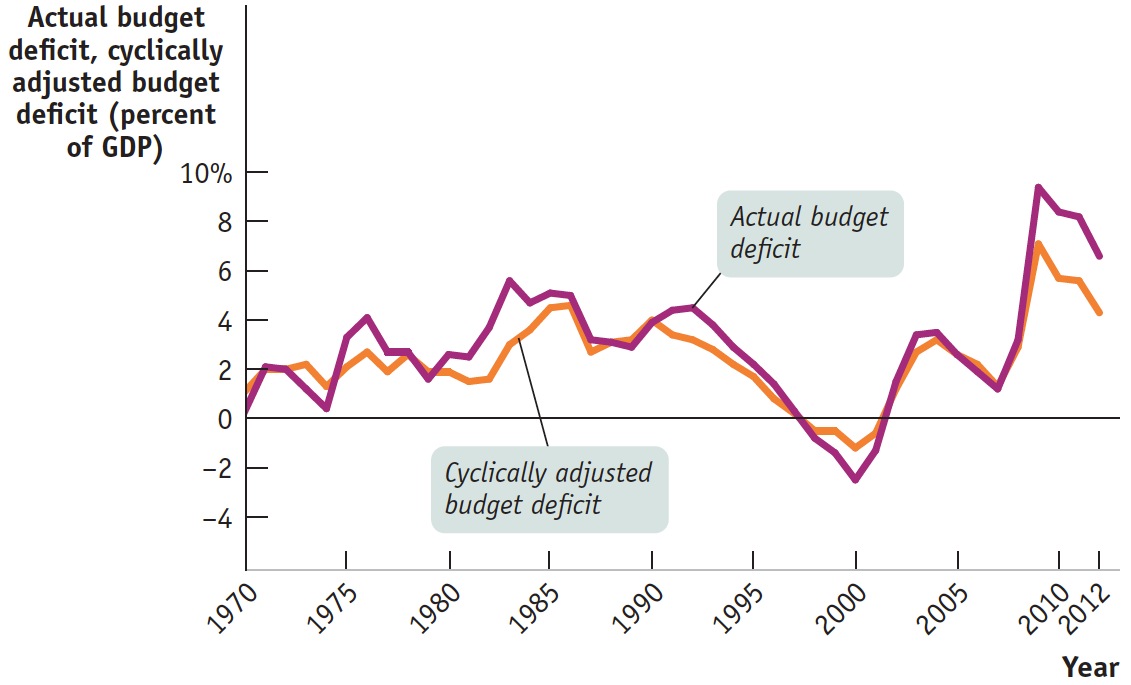

To separate the effect of the business cycle from the effects of other factors, many governments produce an estimate of what the budget balance would be if there were neither a recessionary nor an inflationary gap. The cyclically adjusted budget balance is an estimate of what the budget balance would be if real GDP were exactly equal to potential output. It takes into account the extra tax revenue the government would collect and the transfers it would save if a recessionary gap were eliminated—

Figure 30.3 shows the actual budget deficit and the Congressional Budget Office estimate of the cyclically adjusted budget deficit, both as a percentage of GDP, since 1970. As you can see, the cyclically adjusted budget deficit doesn’t fluctuate as much as the actual budget deficit. In particular, large actual deficits, such as those of 1975 and 1983, are usually caused in part by a depressed economy.

| Figure 30.3 | The Actual Budget Deficit Versus the Cyclically Adjusted Budget Deficit |

Should the Budget Be Balanced?

Persistent budget deficits can cause problems for both the government and the economy. Yet politicians are always tempted to run deficits because this allows them to cater to voters by cutting taxes without cutting spending or by increasing spending without increasing taxes. As a result, there are occasional attempts by policy makers to force fiscal discipline by introducing legislation—

Most economists don’t think so. They believe that the government should only balance its budget on average—

Nonetheless, policy makers concerned about excessive deficits sometimes feel that rigid rules prohibiting—