Monetary Policy in Practice

We have learned that policy makers try to fight recessions. They also try to ensure price stability: low (though usually not zero) inflation. Actual monetary policy reflects a combination of these goals.

AP® Exam Tip

On the AP® exam, if you are asked what policy the central bank could use to correct a particular problem in the economy, don’t just say “expansionary policy” or “contractionary policy.” Identify a specific policy tool (open-

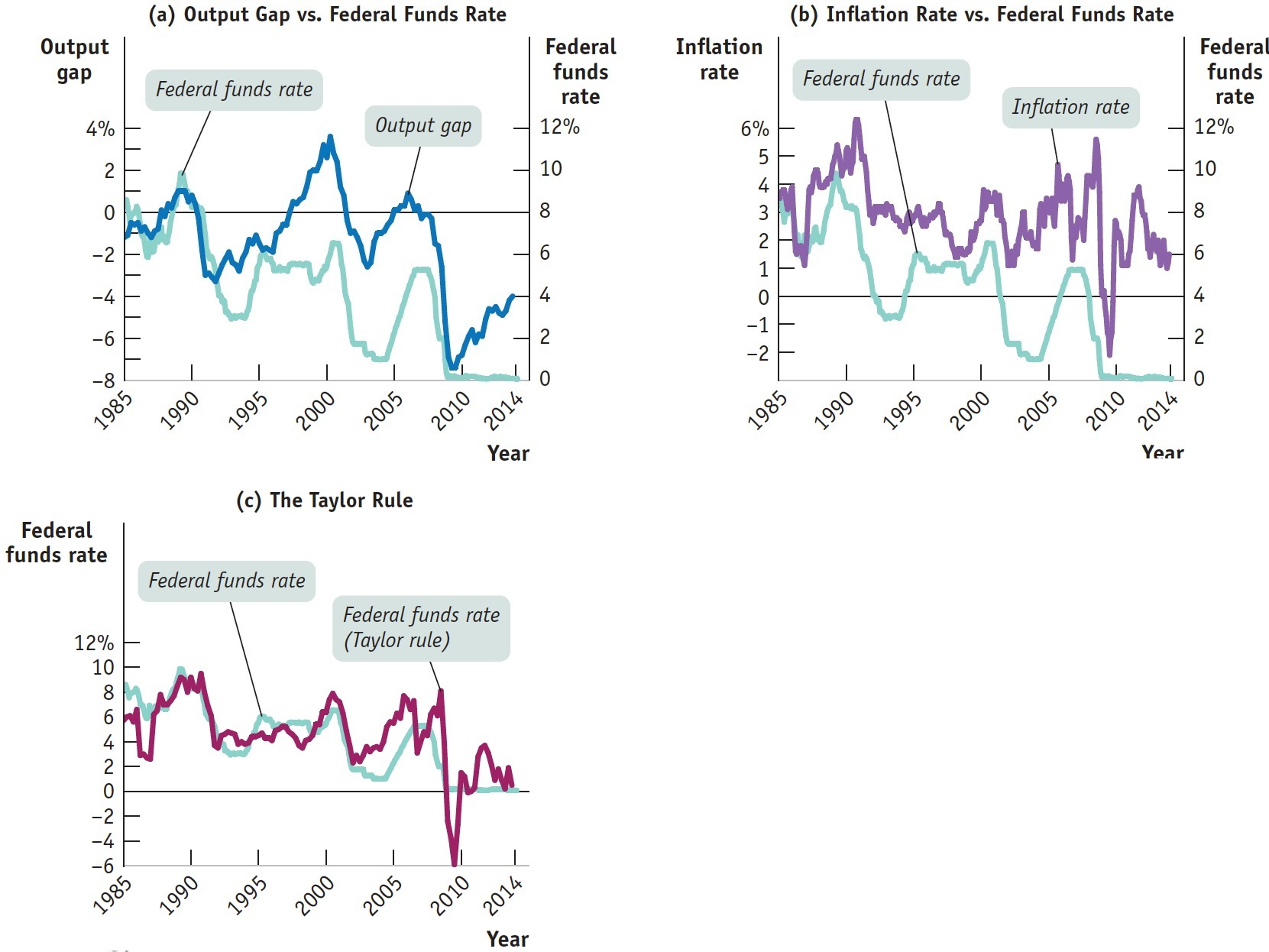

In general, the Federal Reserve and other central banks tend to engage in expansionary monetary policy when actual real GDP is below potential output. Panel (a) of Figure 31.4 shows the U.S. output gap, which we defined as the percentage difference between actual real GDP and potential output, versus the federal funds rate since 1985. (Recall that the output gap is positive when actual real GDP exceeds potential output.) As you can see, the Fed has tended to raise interest rates when the output gap is rising—

| Figure 31.4 | Tracking Monetary Policy Using the Output Gap, Inflation, and the Taylor Rule |

One reason the Fed was willing to keep interest rates low in the late 1990s was that inflation was low. Panel (b) of Figure 31.4 compares the inflation rate, measured as the rate of change in consumer prices excluding food and energy, with the federal funds rate. You can see how low inflation during the mid-

The Taylor rule for monetary policy is a rule for setting the federal funds rate that takes into account both the inflation rate and the output gap.

In 1993, Stanford economist John Taylor suggested that monetary policy should follow a simple rule that takes into account concerns about both the business cycle and inflation. The Taylor rule for monetary policy is a rule for setting the federal funds rate that takes into account both the inflation rate and the output gap. He also suggested that actual monetary policy often looks as if the Federal Reserve was, in fact, more or less following the proposed rule. The rule Taylor originally suggested was as follows:

Federal funds rate = 1 + (1.5 × inflation rate) + (0.5 × output gap)

Panel (c) of Figure 31.4 compares the federal funds rate specified by the Taylor rule with the actual federal funds rate from 1985 to 2010. With the exception of a period beginning in 2009, the Taylor rule does a pretty good job of predicting the Fed’s actual behavior—

Monetary policy, rather than fiscal policy, is the main tool of stabilization policy. Like fiscal policy, it is subject to lags: it takes time for the Fed to recognize economic problems and time for monetary policy to affect the economy. However, since the Fed moves much more quickly than Congress, monetary policy is typically the preferred tool.

Inflation Targeting

Inflation targeting occurs when the central bank sets an explicit target for the inflation rate and sets monetary policy in order to hit that target.

Until 2012, the Fed did not explicitly commit itself to achieving a particular inflation rate. However, in January 2012, Ben Bernanke, the chair of the Federal Reserve at the time, announced that the Fed would set its policy to maintain an approximately 2% inflation rate per year. With that statement, the Fed joined a number of other central banks that have explicit inflation targets. So rather than using the Taylor rule to set monetary policy, they instead announce the inflation rate that they want to achieve—

One major difference between inflation targeting and the Taylor rule is that inflation targeting is forward-

Advocates of inflation targeting argue that it has two key advantages, transparency and accountability. First, economic uncertainty is reduced because the public knows the objective of an inflation-

Critics of inflation targeting argue that it’s too restrictive because there are times when other concerns—

What the Fed Wants, the Fed Gets

What the Fed Wants, the Fed Gets

What’s the evidence that the Fed can actually cause an economic contraction or expansion? You might think that finding such evidence is just a matter of looking at what happens to the economy when interest rates go up or down. But it turns out that there’s a big problem with that approach: the Fed usually changes interest rates in an attempt to tame the business cycle, raising rates if the economy is expanding and reducing rates if the economy is slumping. So, in the actual data, it often looks as if low interest rates go along with a weak economy and high rates go along with a strong economy.

In a famous 1994 paper titled “Monetary Policy Matters,” the macroeconomists Christina Romer and David Romer solved this problem by focusing on episodes in which monetary policy wasn’t a reaction to the business cycle. Specifically, they used minutes from the Federal Open Market Committee and other sources to identify episodes “in which the Federal Reserve in effect decided to attempt to create a recession to reduce inflation.” Contractionary monetary policy is sometimes used to eliminate inflation that has become embedded in the economy, rather than just as a tool of macroeconomic stabilization. In this case, the Fed needs to create a recessionary gap—

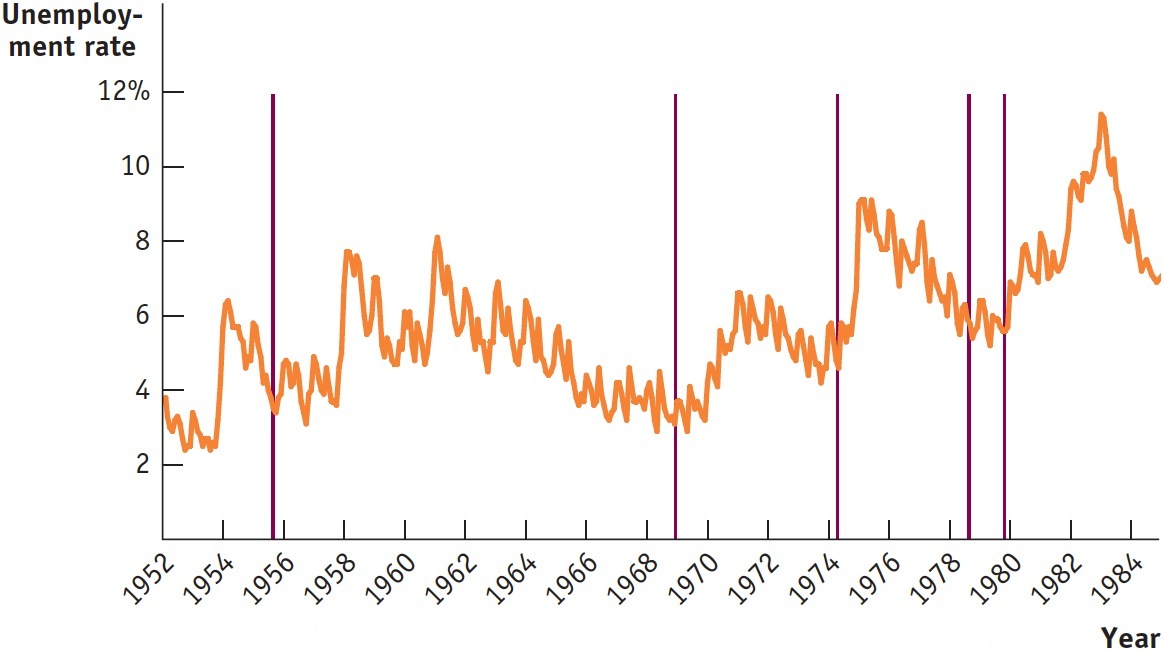

The figure shows the unemployment rate between 1952 and 1984 (orange) and identifies five dates on which, according to Romer and Romer, the Fed decided that it wanted a recession (vertical red lines). In four out of the five cases, the decision to contract the economy was followed, after a modest lag, by a rise in the unemployment rate. On average, Romer and Romer found, the unemployment rate rises by 2 percentage points after the Fed decides that unemployment needs to go up.

So yes, the Fed gets what it wants.