The Great Depression and the Keynesian Revolution

The Great Depression demonstrated, once and for all, that economists cannot safely ignore the short run. Not only was the economic pain severe, it threatened to destabilize societies and political systems. In particular, the economic plunge helped Adolf Hitler rise to power in Germany.

The whole world wanted to know how this economic disaster could be happening and what should be done about it. But because there was no widely accepted theory of the business cycle, economists gave conflicting and, we now believe, often harmful advice. Some believed that only a huge change in the economic system—

Some economists, however, argued that the slump both could have and should have been cured—

Nice metaphor. But what was the nature of the trouble?

Keynes’s Theory

In 1936, Keynes presented his analysis of the Great Depression—

Keynesian economics focuses on the ability of shifts in aggregate demand to influence aggregate output in the short run.

As Samuelson’s description suggests, Keynes’s book is a vast stew of ideas. Keynesian economics mainly reflected two innovations. First, Keynes emphasized the short-

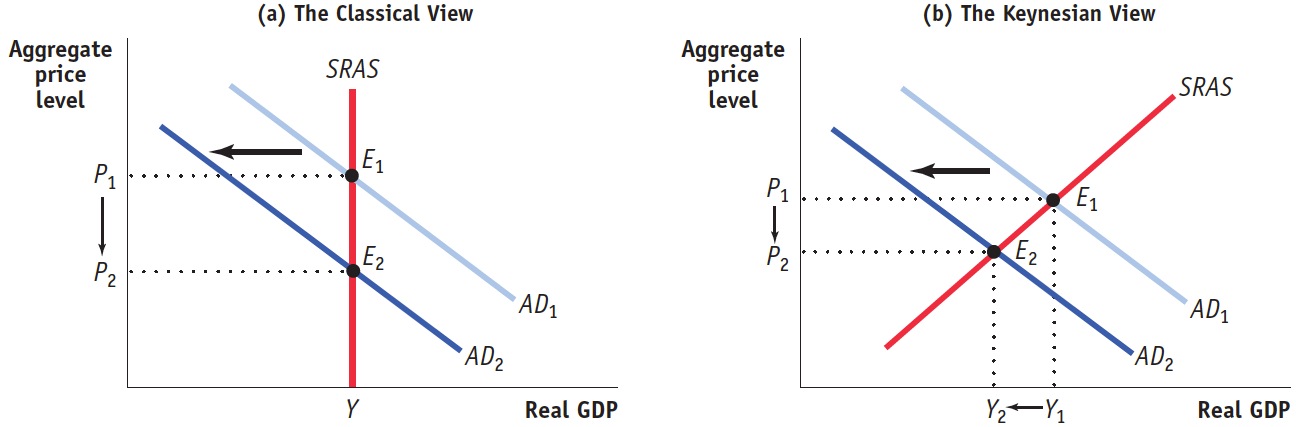

Figure 35.1 illustrates the difference between Keynesian and classical macroeconomics. Both panels of the figure show the short-

| Figure 35.1 | Classical Versus Keynesian Macroeconomics |

Panel (a) shows the classical view: the short-

Second, classical economists emphasized the role of changes in the money supply in shifting the aggregate demand curve, paying little attention to other factors. Keynes, however, argued that other factors, especially changes in “animal spirits”—these days usually referred to with the bland term business confidence—are mainly responsible for business cycles. Before Keynes, economists often argued that a decline in business confidence would have no effect on either the aggregate price level or aggregate output, as long as the money supply stayed constant. Keynes offered a very different picture.

Keynes’s ideas have penetrated deeply into the public consciousness, to the extent that many people who have never heard of Keynes, or have heard of him but think they disagree with his theory, use Keynesian ideas all the time. For example, suppose that a business commentator says something like this: “Because of a decline in business confidence, investment spending slumped, causing a recession.” Whether the commentator knows it or not, that statement is pure Keynesian economics.

Keynes himself more or less predicted that his ideas would become part of what “everyone knows.” In another famous passage, this from the end of The General Theory, he wrote: “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

Policy to Fight Recessions

Macroeconomic policy activism is the use of monetary and fiscal policy to smooth out the business cycle.

The main practical consequence of Keynes’s work was that it legitimized macroeconomic policy activism—the use of monetary and fiscal policy to smooth out the business cycle.

Macroeconomic policy activism wasn’t something completely new. Before Keynes, many economists had argued for using monetary expansion to fight economic downturns—

But these efforts were half-

The End of the Great Depression

The End of the Great Depression

It would make a good story if Keynes’s ideas had led to a change in economic policy that brought the Great Depression to an end. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. Still, the way the Depression ended did a lot to convince economists that Keynes was right.

The basic message many of the young economists who adopted Keynes’s ideas in the 1930s took from his work was that economic recovery requires aggressive fiscal expansion—

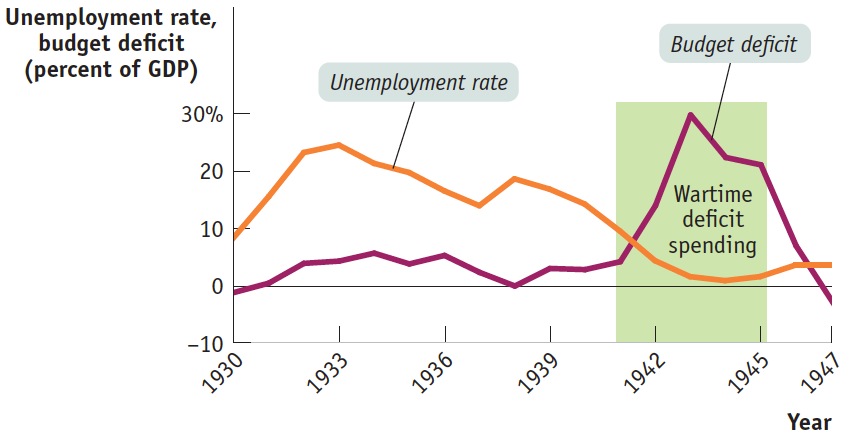

The figure here shows the U.S. unemployment rate and the federal budget deficit as a share of GDP from 1930 to 1947. As you can see, deficit spending during the 1930s was on a modest scale. In 1940, as the risk of war grew larger, the United States began a large military buildup, and the budget moved deep into deficit. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the country began deficit spending on an enormous scale: in fiscal 1943, which began in July 1942, the deficit was 30% of GDP. Today that would be a deficit of $4.3 trillion.

And the economy recovered. World War II wasn’t intended as a Keynesian fiscal policy, but it demonstrated that expansionary fiscal policy can, in fact, create jobs in the short run.

Today, by contrast, there is broad consensus about the useful role monetary and fiscal policy can play in fighting recessions. The 2004 Economic Report of the President was issued by a conservative Republican administration that was generally opposed to government intervention in the economy. Yet its view on economic policy in the face of recession was far more like that of Keynes than like that of most economists before 1936.

It would be wrong, however, to suggest that Keynes’s ideas have been fully accepted by modern macroeconomists. In the decades that followed the publication of The General Theory, Keynesian economics faced a series of challenges, some of which succeeded in modifying the macroeconomic consensus in important ways.