Why Growth Rates Differ

In 1820, according to estimates by the economic historian Angus Maddison, Mexico had somewhat higher real GDP per capita than Japan. Today, Japan has higher real GDP per capita than most European nations and Mexico is a poor country, though by no means among the poorest. The difference? Over the long run, real GDP per capita grew at 1.9% per year in Japan but at only 1.2% per year in Mexico.

As this example illustrates, even small differences in growth rates have large consequences over the long run. So why do growth rates differ across countries and across periods of time?

Explaining Differences in Growth Rates

As one might expect, economies with rapid growth tend to be economies that add physical capital, increase their human capital, or experience rapid technological progress. Striking economic success stories, like Japan in the 1950s and 1960s or China today, tend to be countries that do all three: rapidly add to their physical capital, upgrade their educational level, and make fast technological progress.

Adding to Physical Capital One reason for differences in growth rates among countries is that some countries are increasing their stock of physical capital much more rapidly than others, through high rates of investment spending. In the 1960s, Japan was the fastest-

AP® Exam Tip

Growth rates between nations differ due to differing levels of physical capital, human capital, and technology. Past AP® exams have tested economic growth concepts but not actual growth rates.

Where does the money for high investment spending come from? We have already analyzed how financial markets channel savings into investment spending. The key point is that investment spending must be paid for either out of savings from domestic households or by an inflow of foreign capital—

Adding to Human Capital Just as countries differ substantially in the rate at which they add to their physical capital, there have been large differences in the rate at which countries add to their human capital through education.

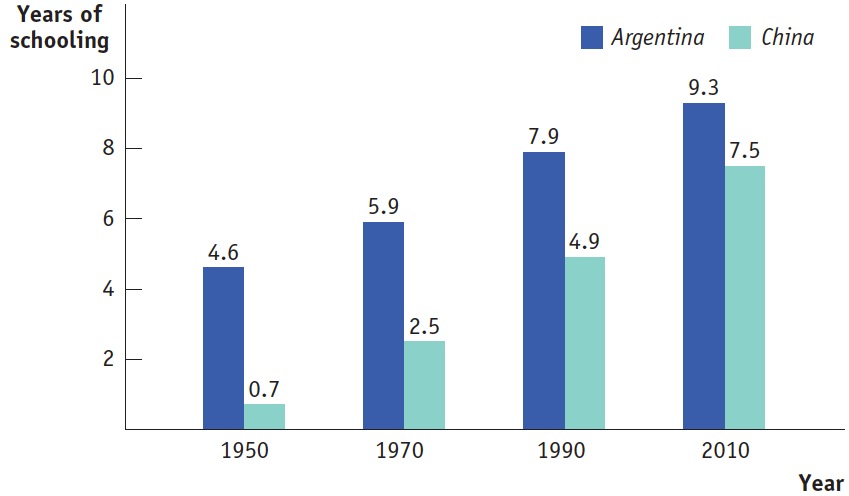

A case in point is the comparison between Argentina and China. In both countries, the average educational level has risen steadily over time, but it has risen much faster in China. Figure 39.1 shows the average years of education of adults in China, which we have highlighted as a spectacular example of long-

| Figure 39.1 | China’s Students Are Catching Up |

Research and development, or R&D, is spending to create and implement new technologies.

Technological Progress The advance of technology is a key force behind economic growth. What drives technology?

Scientific advances make new technologies possible. To take the most spectacular example in today’s world, the semiconductor chip—

But science alone is not enough: scientific knowledge must be translated into useful products and processes. And that often requires devoting a lot of resources to research and development, or R&D, spending to create new technologies and prepare them for practical use.

Inventing R&D

Inventing R&D

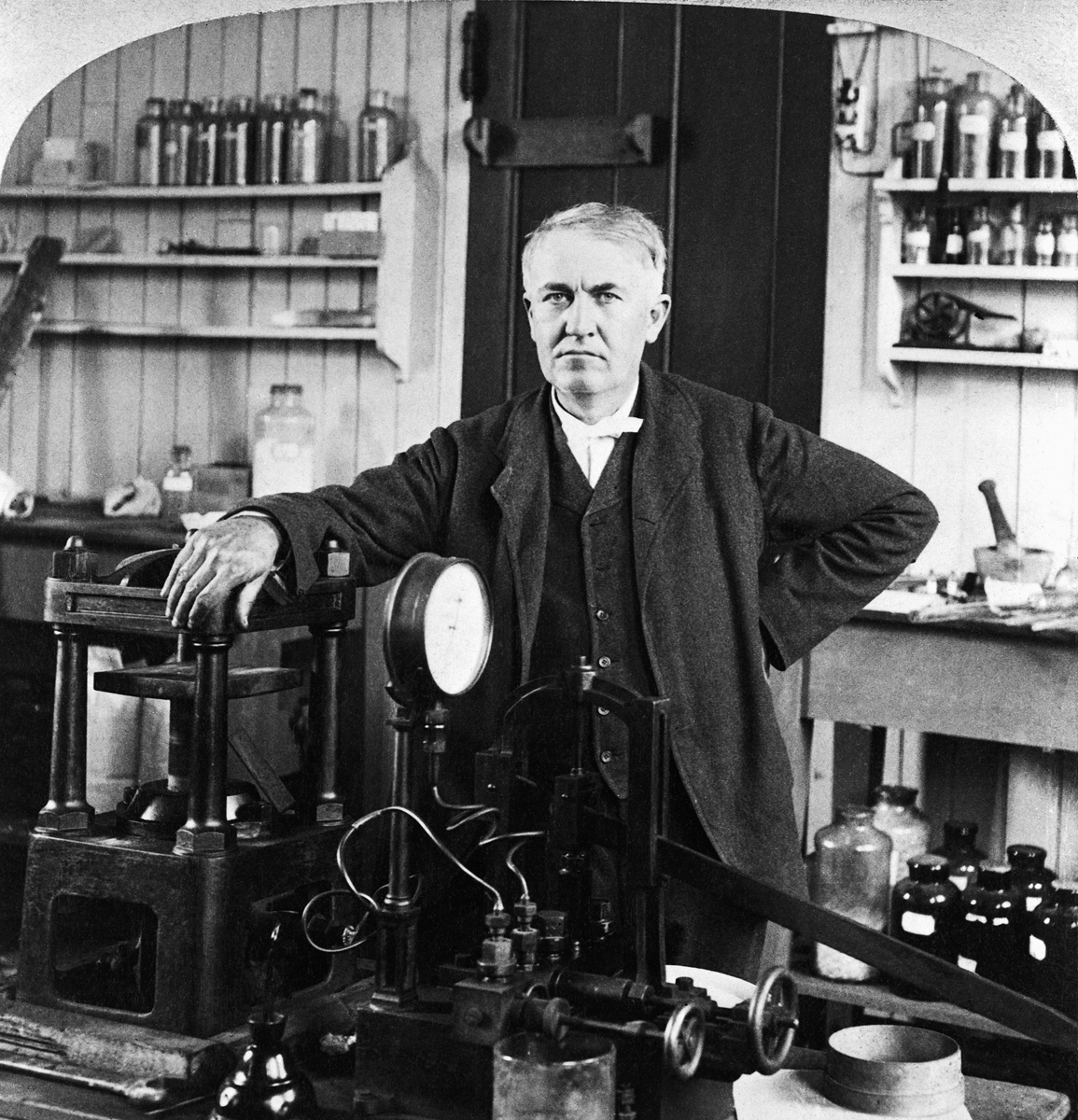

Thomas Edison is best known as the inventor of the lightbulb and the phonograph. But his biggest invention may surprise you: he invented research and development.

Before Edison’s time, of course, there had been many inventors. Some of them worked in teams. But in 1875 Edison created something new: his Menlo Park, New Jersey, laboratory. It employed 25 men full-

Edison’s Menlo Park lab is now a museum. “To name a few of the products that were developed in Menlo Park,” says the museum’s website, “we can list the following: the carbon button mouthpiece for the telephone, the phonograph, the incandescent lightbulb and the electrical distribution system, the electric train, ore separation, the Edison effect bulb, early experiments in wireless, the grasshopper telegraph, and improvements in telegraphic transmission.”

You could say that before Edison’s lab, technology just sort of happened: people came up with ideas, but businesses didn’t plan to make continuous technological progress. Now R&D operations, often much bigger than Edison’s original team, are standard practice throughout the business world.

Although some research and development is conducted by governments, much R&D is paid for by the private sector, as discussed in the FYI box. The United States became the world’s leading economy in large part because American businesses were among the first to make systematic research and development a part of their operations.

Developing new technology is one thing; applying it is another. There have often been notable differences in the pace at which different countries take advantage of new technologies. America’s surge in productivity growth after 1995, as firms learned to make use of information technology, was at least initially not matched in Europe.

The Role of Government in Promoting Economic Growth

AP® Exam Tip

Don’t automatically assume that government spending will have an impact on economic growth. Some government spending is on things that are not sources of economic growth.

Governments can play an important role in promoting—

Roads, power lines, ports, information networks, and other underpinnings for economic activity are known as infrastructure.

Governments and Physical Capital Governments play an important direct role in building infrastructure: roads, power lines, ports, information networks, and other parts of an economy’s physical capital that provide an underpinning, or foundation, for economic activity. Although some infrastructure is provided by private companies, much of it is either provided by the government or requires a great deal of government regulation and support. Ireland, whose economy really took off in the 1990s, is often cited as an example of the importance of government-

Poor infrastructure—

Perhaps the most crucial infrastructure is something we rarely think about: basic public health measures in the form of a clean water supply and disease control. As we’ll see in the next section, poor health infrastructure is a major obstacle to economic growth in poor countries, especially those in Africa.

Governments also play an important indirect role in making high rates of private investment spending possible. Both the amount of savings and the ability of an economy to direct savings into productive investment spending depend on the economy’s institutions, notably its financial system. In particular, a well-

Governments and Human Capital An economy’s physical capital is created mainly through investment spending by individuals and private companies. Much of an economy’s human capital, by contrast, is the result of government spending on education. Governments pay for the great bulk of primary and secondary education, although individuals pay a significant share of the costs of higher education.

As a result, differences in the rate at which countries add to their human capital largely reflect government policy. For example, East Asia now has a more educated population than Latin America. This isn’t because East Asia is richer than Latin America and so can afford to spend more on education. Until very recently, East Asia, on average, was poorer than Latin America. Instead, it reflects the fact that Asian governments made broad education of the population a higher priority.

Governments and Technology Technological progress is largely the result of private initiative. But much important R&D is done by government agencies. For example, Brazil’s agricultural boom was made possible by government researchers who discovered that adding crucial nutrients to the soil would allow crops to be grown on previously unusable land. They also developed new varieties of soybeans and breeds of cattle that flourish in Brazil’s tropical climate.

Political Stability, Property Rights, and Excessive Government Intervention There’s not much point in investing in a business if rioting mobs are likely to destroy it. And why save your money if someone with political connections can steal it? Political stability and protection of property rights are crucial ingredients in long-

Long-

Americans take these preconditions for granted, but they are by no means guaranteed. Aside from the disruption caused by war or revolution, many countries find that their economic growth suffers due to corruption among the government officials who should be enforcing the law. For example, until 1991 the Indian government imposed many bureaucratic restrictions on businesses, which often had to bribe government officials to get approval for even routine activities—

The Brazilian Breadbasket

The Brazilian Breadbasket

A wry Brazilian joke says that “Brazil is the country of the future—

In recent years, however, Brazil’s economy has made a better showing, especially in agriculture. This success depends on exploiting a natural resource, the tropical savanna land known as the cerrado. Until a quarter century ago, the land was considered unsuitable for farming. A combination of three factors changed that: technological progress due to research and development, improved economic policies, and greater physical capital.

The Brazilian Enterprise for Agricultural and Livestock Research, a government-

What still limits Brazil’s growth? Infrastructure. According to a report in the New York Times, Brazilian farmers are “concerned about the lack of reliable highways, railways and barge routes, which adds to the cost of doing business.” Recognizing this, the Brazilian government is investing in infrastructure, and Brazilian agriculture is continuing to expand. The country has already overtaken the United States as the world’s largest beef exporter and may not be far behind in soybeans.

Even when governments aren’t corrupt, excessive government intervention can be a brake on economic growth. If large parts of the economy are supported by government subsidies, protected from imports, or otherwise insulated from competition, productivity tends to suffer because of a lack of incentives. As we saw in Module 38, excessive government intervention is one often-