Measuring Responses to Other Changes

We stated earlier that economists use the concept of elasticity to measure the responsiveness of one variable to changes in another. However, up to this point we have focused on the price elasticity of demand. Now that we have used elasticity to measure the responsiveness of quantity demanded to changes in price, we can go on to look at how elasticity is used to understand the relationship between other important variables in economics.

The quantity of a good demanded depends not only on the price of that good but also on other variables. In particular, demand curves shift because of changes in the prices of related goods and changes in consumers’ incomes. It is often important to have a measure of these other effects, and the best measures are—you guessed it—elasticities. Specifically, we can best measure how the demand for a good is affected by prices of other goods using a measure called the cross-price elasticity of demand, and we can best measure how demand is affected by changes in income using the income elasticity of demand.

Finally, we can also use elasticity to measure supply responses. The price elasticity of supply measures the responsiveness of the quantity supplied to changes in price.

The Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand

AP® Exam Tip

A negative cross-price elasticity identifies a complement (one you buy less of when the price of the other goes up). A positive cross-price elasticity identifies a substitute (one you buy more of when the price of the other goes up).

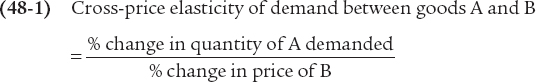

The cross-price elasticity of demand between two goods measures the effect of the change in one good’s price on the quantity demanded of the other good. It is equal to the percent change in the quantity demanded of one good divided by the percent change in the other good’s price.

The demand for a good is often affected by the prices of other, related goods—goods that are substitutes or complements. A change in the price of a related good shifts the demand curve of the original good, reflecting a change in the quantity demanded at any given price. The strength of such a “cross” effect on demand can be measured by the cross-price elasticity of demand, defined as the ratio of the percent change in the quantity demanded of one good to the percent change in the price of another.

Page 478

When two goods are substitutes, like hot dogs and hamburgers, the cross-price elasticity of demand is positive: a rise in the price of hot dogs increases the demand for hamburgers—that is, it causes a rightward shift of the demand curve for hamburgers. If the goods are close substitutes, the cross-price elasticity will be positive and large; if they are not close substitutes, the cross-price elasticity will be positive and small. So when the cross-price elasticity of demand is positive, its size is a measure of how closely substitutable the two goods are.

When two goods are complements, like hot dogs and hot dog buns, the cross-price elasticity is negative: a rise in the price of hot dogs decreases the demand for hot dog buns—that is, it causes a leftward shift of the demand curve for hot dog buns. As with substitutes, the size of the cross-price elasticity of demand between two complements tells us how strongly complementary they are: if the cross-price elasticity is only slightly below zero, they are weak complements; if it is very negative, they are strong complements.

Note that in the case of the cross-price elasticity of demand, the sign (plus or minus) is very important: it tells us whether the two goods are complements or substitutes. So we cannot drop the minus sign as we did for the price elasticity of demand.

Our discussion of the cross-price elasticity of demand is a useful place to return to a point we made earlier: elasticity is a unit-free measure—that is, it doesn’t depend on the units in which goods are measured.

To see the potential problem, suppose someone told you that “if the price of hot dog buns rises by $0.30, Americans will buy 10 million fewer hot dogs this year.” If you’ve ever bought hot dog buns, you’ll immediately wonder: is that a $0.30 increase in the price per bun, or is it a $0.30 increase in the price per package of buns? It makes a big difference what units we are talking about! However, if someone says that the cross-price elasticity of demand between buns and hot dogs is–0.3, you’ll know that a 1% increase in the price of buns causes a 0.3% decrease in the quantity of hot dogs demanded, regardless of whether buns are sold individually or by the package. So elasticity is defined as a ratio of percent changes, which avoids confusion over units.

The Income Elasticity of Demand

AP® Exam Tip

A negative income elasticity identifies an inferior good (one you buy less of when your income goes up). A positive income elasticity identifies a normal good (one you buy more of when your income goes up).

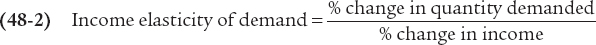

The income elasticity of demand is the percent change in the quantity of a good demanded when a consumer’s income changes divided by the percent change in the consumer’s income.

The income elasticity of demand measures how changes in income affect the demand for a good. It indicates whether a good is normal or inferior and specifies how responsive demand for the good is to changes in income. Having learned the price and cross-price elasticity formulas, the income elasticity formula will look familiar:

Just as the cross-price elasticity of demand between two goods can be either positive or negative, depending on whether the goods are substitutes or complements, the income elasticity of demand for a good can also be either positive or negative. Recall that goods can be either normal goods, for which demand increases when income rises, or inferior goods, for which demand decreases when income rises. These definitions relate directly to the sign of the income elasticity of demand:

When the income elasticity of demand is positive, the good is a normal good.

When the income elasticity of demand is negative, the good is an inferior good.

Page 479

Where Have All the Farmers Gone?

Where Have All the Farmers Gone?

What percentage of Americans live on farms? Sad to say, the U.S. government no longer publishes that number. In 1991, the official percentage was 1.9, but in that year the government decided it was no longer a meaningful indicator of the size of the agricultural sector because a large proportion of those who live on farms actually make their living doing something else. In the days of the Founding Fathers, the great majority of Americans lived on farms. As recently as the 1940s, one American in six—or approximately 17%—still did.

Why do so few people now live and work on farms in the United States? There are two main reasons, both involving elasticities.

First, the income elasticity of demand for food is much less than 1—food demand is income-inelastic. As consumers grow richer, other things equal, spending on food rises less than in proportion to income. As a result, as the U.S. economy has grown, the share of income spent on food—and therefore the share of total U.S. income earned by farmers—has fallen.

Second, agriculture has been a technologically progressive sector for approximately 150 years in the United States, with steadily increasing yields over time. You might think that technological progress would be good for farmers. But competition among farmers means that technological progress leads to lower food prices. Meanwhile, the demand for food is price-inelastic, so falling prices of agricultural goods, other things equal, reduce the total revenue of farmers. That’s right: progress in farming is good for consumers but bad for farmers.

Photodisc

The combination of these effects explains the relative decline of farming. Even if farming weren’t such a technologically progressive sector, the low income elasticity of demand for food would ensure that the income of farmers grows more slowly than the economy as a whole. The combination of rapid technological progress in farming with price-inelastic demand for farm products reinforces this effect, further reducing the growth of farm income. In short, the U.S. farm sector has been a victim of success—the U.S. economy’s success as a whole (which reduces the importance of spending on food) and its own success in increasing yields.

Economists often use estimates of the income elasticity of demand to predict which industries will grow most rapidly as the incomes of consumers grow over time. In doing this, they often find it useful to make a further distinction among normal goods, identifying which are income-elastic and which are income-inelastic.

The demand for a good is income-elastic if the income elasticity of demand for that good is greater than 1.

The demand for a good is income-inelastic if the income elasticity of demand for that good is positive but less than 1.

The demand for a good is income-elastic if the income elasticity of demand for that good is greater than 1. When income rises, the demand for income-elastic goods rises faster than income. Luxury goods, such as second homes and international travel, tend to be income-elastic. The demand for a good is income-inelastic if the income elasticity of demand for that good is positive but less than 1. When income rises, the demand for income-inelastic goods rises as well, but more slowly than income. Necessities such as food and clothing tend to be income-inelastic.