Comparative Advantage and Gains from Trade

The production possibilities curve model is particularly useful for illustrating gains from trade—

It’s obvious that there will be potential gains from trade if the two castaways do different things particularly well. For example, if Tom is a skilled fisherman and Hank is very good at climbing trees, clearly it makes sense for Tom to catch fish and Hank to gather coconuts—

But one of the most important insights in all of economics is that there are gains from trade even if one of the trading parties isn’t especially good at anything. Suppose, for example, that Hank is less well suited to primitive life than Tom; he’s not nearly as good at catching fish, and compared to Tom, even his coconut-

For the purposes of this example, let’s go back to the simple case of straight-

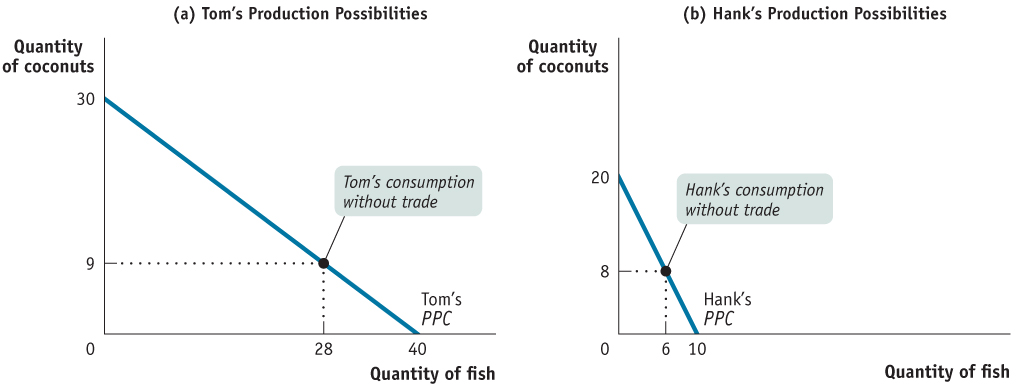

| Figure 4.1 | Production Possibilities for Two Castaways |

Panel (b) of Figure 4.1 shows Hank’s production possibilities. Like Tom’s, Hank’s production possibilities curve is a straight line, implying a constant opportunity cost of fish in terms of coconuts. His production possibilities curve has a constant slope of −2. Hank is less productive all around: at most he can produce 10 fish or 20 coconuts. But he is particularly bad at fishing: whereas Tom sacrifices ¾ of a coconut per fish caught, for Hank the opportunity cost of a fish is 2 whole coconuts. Table 4.1 summarizes the two castaways’ opportunity costs of fish and coconuts.

Now, Tom and Hank could go their separate ways, each living on his own side of the island, catching his own fish and gathering his own coconuts. Let’s suppose that they start out that way and make the consumption choices shown in Figure 4.1: in the absence of trade, Tom consumes 28 fish and 9 coconuts per week, while Hank consumes 6 fish and 8 coconuts.

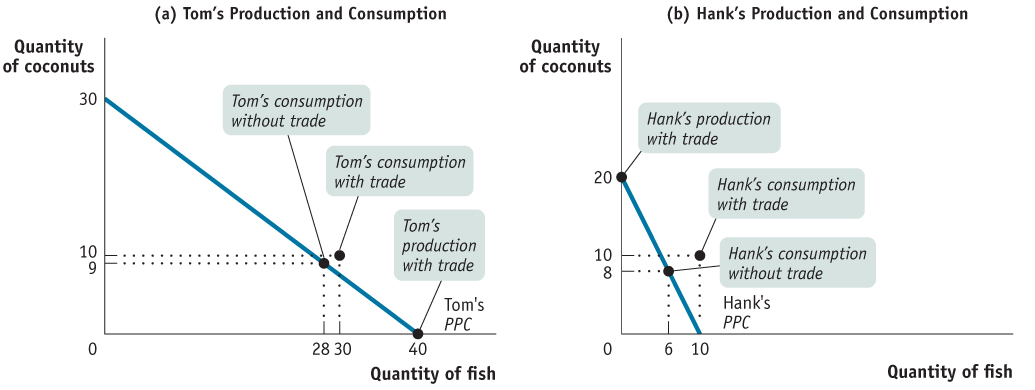

But is this the best they can do? No, it isn’t. Given that the two castaways have different opportunity costs, they can strike a deal that makes both of them better off. Table 4.2 shows how such a deal works: Tom specializes in the production of fish, catching 40 per week, and gives 10 to Hank. Meanwhile, Hank specializes in the production of coconuts, gathering 20 per week, and gives 10 to Tom. The result is shown in Figure 4.2. Tom now consumes more of both goods than before: instead of 28 fish and 9 coconuts, he consumes 30 fish and 10 coconuts. Hank also consumes more, going from 6 fish and 8 coconuts to 10 fish and 10 coconuts. As Table 4.2 also shows, both Tom and Hank experience gains from trade: Tom’s consumption of fish increases by two, and his consumption of coconuts increases by one. Hank’s consumption of fish increases by four, and his consumption of coconuts increases by two.

| Figure 4.2 | Comparative Advantage and Gains from Trade |

So both castaways are better off when they each specialize in what they are good at and trade with each other. It’s a good idea for Tom to catch the fish for both of them, because his opportunity cost of a fish is only ¾ of a coconut not gathered versus 2 coconuts for Hank. Correspondingly, it’s a good idea for Hank to gather coconuts for both of them.

Or we could describe the situation in a different way. Because Tom is so good at catching fish, his opportunity cost of gathering coconuts is high:  of a fish not caught for every coconut gathered. Because Hank is a pretty poor fisherman, his opportunity cost of gathering coconuts is much less, only ½ of a fish per coconut.

of a fish not caught for every coconut gathered. Because Hank is a pretty poor fisherman, his opportunity cost of gathering coconuts is much less, only ½ of a fish per coconut.

An individual has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if the opportunity cost of producing the good or service is lower for that individual than for other people.

An individual has a comparative advantage in producing something if the opportunity cost of that production is lower for that individual than for other people. In other words, Hank has a comparative advantage over Tom in producing a particular good or service if Hank’s opportunity cost of producing that good or service is lower than Tom’s. In this case, Hank has a comparative advantage in gathering coconuts and Tom has a comparative advantage in catching fish.

An individual has an absolute advantage in producing a good or service if he or she can make more of it with a given amount of time and resources. Having an absolute advantage is not the same thing as having a comparative advantage.

Notice that Tom is actually better than Hank at producing both goods: Tom can catch more fish in a week, and he can also gather more coconuts. This means that Tom has an absolute advantage in both activities: he can produce more output with a given amount of input (in this case, his time) than Hank can. It might seem as though Tom has nothing to gain from trading with less competent Hank. But we’ve just seen that Tom can indeed benefit from a deal with Hank, because comparative, not absolute, advantage is the basis for mutual gain. It doesn’t matter that it takes Hank more time to gather a coconut; what matters is that for him the opportunity cost of that coconut in terms of fish is lower. So, despite his absolute disadvantage in both activities, Hank has a comparative advantage in coconut gathering. Meanwhile Tom, who can use his time better by catching fish, has a comparative disadvantage in coconut gathering.

Mutually Beneficial Terms of Trade

The terms of trade indicate the rate at which one good can be exchanged for another.

The terms of trade indicate the rate at which one good can be exchanged for another. In our story, Tom and Hank traded 10 coconuts for 10 fish, so each coconut traded for 1 fish. Why not some other terms of trade, such as ¾ fish per coconut? Indeed, there are many terms of trade that would make both Tom and Hank better off than if they didn’t trade. But there are also terms that Tom or Hank would certainly reject. For example, Tom would not trade 2 fish per coconut, because he only gives up  fish per coconut without trade.

fish per coconut without trade.

To find the range of mutually beneficial terms of trade for a coconut, look at each person’s opportunity cost of producing a coconut. Any price per coconut between the opportunity cost of the coconut producer and the opportunity cost of the coconut buyer will make both sides better off than in the absence of trade. We know that Hank will produce coconuts because he has a comparative advantage in gathering coconuts. Hank’s opportunity cost is ½ fish per coconut. Tom, the buyer of coconuts, has an opportunity cost of  fish per coconut. So any terms of trade between ½ fish per coconut and

fish per coconut. So any terms of trade between ½ fish per coconut and  fish per coconut would benefit both Tom and Hank.

fish per coconut would benefit both Tom and Hank.

To understand why, consider the opportunity costs summarized in Table 4.1. When Hank doesn’t trade with Tom, Hank can gain ½ fish by giving up a coconut, because his opportunity cost of each coconut is ½ fish. Hank will clearly reject any deal with Tom that provides him with less than ½ fish per coconut—

When Tom doesn’t trade with Hank, Tom gives up  fish to get a coconut—

fish to get a coconut— fish. Tom will reject any deal that requires him to pay more than

fish. Tom will reject any deal that requires him to pay more than  fish per coconut. But Tom benefits from trade if he pays less than

fish per coconut. But Tom benefits from trade if he pays less than  fish per coconut. The terms of 1 fish per coconut are thus acceptable to Tom as well. Both islanders would also be made better off by terms of ¾ fish per coconut or

fish per coconut. The terms of 1 fish per coconut are thus acceptable to Tom as well. Both islanders would also be made better off by terms of ¾ fish per coconut or  fish per coconut or any other price between ½ fish and

fish per coconut or any other price between ½ fish and  fish per coconut. The islanders’ negotiation skills determine where the terms of trade fall within that range.

fish per coconut. The islanders’ negotiation skills determine where the terms of trade fall within that range.

So remember, Tom and Hank will engage in trade only if the “price” of the good each person obtains from trade is less than his own opportunity cost of producing the good. The same is true for international trade. Whenever two parties trade voluntarily, for each good, the terms of trade are found between the opportunity cost of the producer and the opportunity cost of the buyer.

AP® Exam Tip

The producer with the absolute advantage can produce the largest quantity of the good. However, it is the producer with the comparative advantage, and not necessarily the one with the absolute advantage, who should specialize in the production of that good to achieve mutual gains from trade.

The story of Tom and Hank clearly simplifies reality. Yet it teaches us some very important lessons that also apply to the real economy. First, the story provides a clear illustration of the gains from trade. By agreeing to specialize and provide goods to each other, Tom and Hank can produce more; therefore, both are better off than if each tried to be self-

The idea of comparative advantage applies to many activities in the economy. Perhaps its most important application is in trade—

Comparative Advantage and International Trade

Look at the label on a manufactured good sold in the United States, and there’s a good chance you will find that it was produced in some other country—

Should we celebrate this international exchange of goods and services, or should it cause us concern? Politicians and the public often question the desirability of international trade, arguing that the nation should produce goods for itself rather than buy them from foreigners. Industries around the world demand protection from foreign competition: Japanese farmers want to keep out American rice, and American steelworkers want to keep out European steel. These demands are often supported by public opinion.

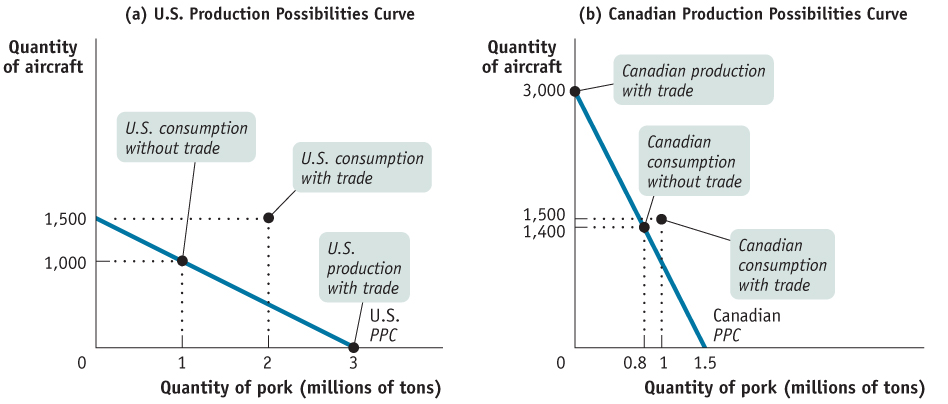

Economists, however, have a very positive view of international trade. Why? Because they view it in terms of comparative advantage. Figure 4.3 shows, with a simple example, how international trade can be interpreted in terms of comparative advantage. Although the example is hypothetical, it is based on an actual pattern of international trade: American exports of pork to Canada and Canadian exports of aircraft to the United States. Panels (a) and (b) illustrate hypothetical production possibilities curves for the United States and Canada, with pork measured on the horizontal axis and aircraft measured on the vertical axis. The U.S. production possibilities curve is flatter than the Canadian production possibilities curve, implying that producing one more ton of pork costs fewer aircraft in the United States than it does in Canada. This means that the United States has a comparative advantage in pork and Canada has a comparative advantage in aircraft.

| Figure 4.3 | Comparative Advantage and International Trade |

Although the consumption points in Figure 4.3 are hypothetical, they illustrate a general principle: just like the example of Tom and Hank, the United States and Canada can both achieve mutual gains from trade. If the United States concentrates on producing pork and sells some of its output to Canada, while Canada concentrates on aircraft and sells some of its output to the United States, both countries can consume more than if they insisted on being self-

Moreover, these mutual gains don’t depend on each country’s being better at producing one kind of good. Even if one country has, say, higher output per person-

Rich Nation, Poor Nation

Rich Nation, Poor Nation

Try taking off your clothes—

Why are these countries so much poorer than the United States? The immediate reason is that their economies are much less productive—firms in these countries are just not able to produce as much from a given quantity of resources as comparable firms in the United States or other wealthy countries. Why countries differ so much in productivity is a deep question—

If the economies of these countries are so much less productive than ours, how is it that they make so much of our clothing? Why don’t we do it for ourselves?

The answer is “comparative advantage.” Just about every industry in Bangladesh is much less productive than the corresponding industry in the United States. But the productivity difference between rich and poor countries varies across goods; there is a very great difference in the production of sophisticated goods such as aircraft but not as great a difference in the production of simpler goods such as clothing. So Bangladesh’s position with regard to clothing production is like Hank’s position with respect to coconut gathering: he’s not as good at it as his fellow castaway is, but it’s the thing he does comparatively well.

Although Bangladesh is at an absolute disadvantage compared with the United States in almost everything, it has a comparative advantage in clothing production. This means that both the United States and Bangladesh are able to consume more because they specialize in producing different things, with Bangladesh supplying our clothing and the United States supplying Bangladesh with more sophisticated goods.