The Effects of Taxes on Total Surplus

An excise tax is a tax on sales of a particular good or service.

To understand the economics of taxes, it’s helpful to look at a simple type of tax known as an excise tax—a tax charged on each unit of a particular good or service that is sold. Most tax revenue in the United States comes from other kinds of taxes, but excise taxes are common. For example, there are excise taxes on gasoline, cigarettes, and foreign-

The Effect of an Excise Tax on Quantities and Prices

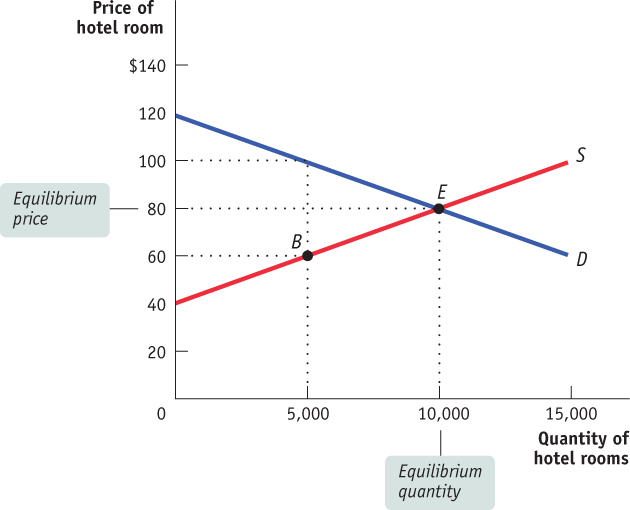

Suppose that the supply and demand for hotel rooms in the city of Potterville are as shown in Figure 50.5. We’ll make the simplifying assumption that all hotel rooms are the same. In the absence of taxes, the equilibrium price of a room is $80 per night and the equilibrium quantity of hotel rooms rented is 10,000 per night.

| Figure 50.5 | The Supply and Demand for Hotel Rooms in Potterville |

Now suppose that Potterville’s government imposes an excise tax of $40 per night on hotel rooms—

What does this imply about the supply curve for hotel rooms in Potterville? To answer this question, we must compare the incentives of hotel owners pre-

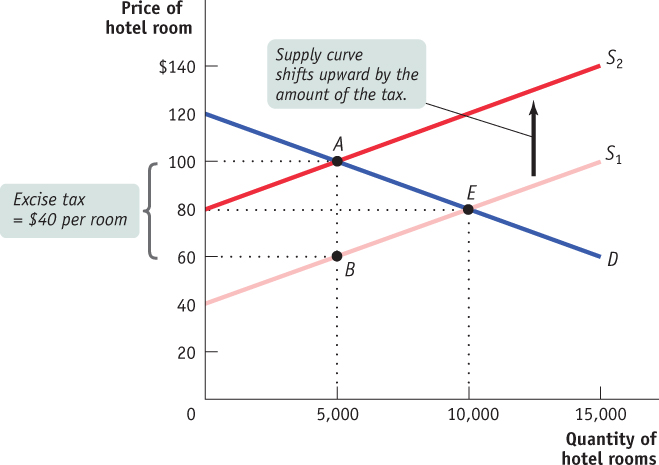

The upward shift of the supply curve caused by the tax is shown in Figure 50.6, where S1 is the pre-

| Figure 50.6 | An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Owners |

AP® Exam Tip

A tax of a certain amount or percent per unit of a good, such as a $1 per unit excise tax or a 5% sales tax, generally increases the equilibrium price and decreases the equilibrium quantity.

Let’s check this again. How do we know that 5,000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $100? Because the price net of tax is $60, and according to the original supply curve, 5,000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $60, as shown by point B in Figure 50.6.

An excise tax drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. As a result of this wedge, consumers pay more and producers receive less. In our example, consumers—

It’s important to recognize that as we’ve described it, Potterville’s hotel tax is a tax on the hotel owners, not their guests—

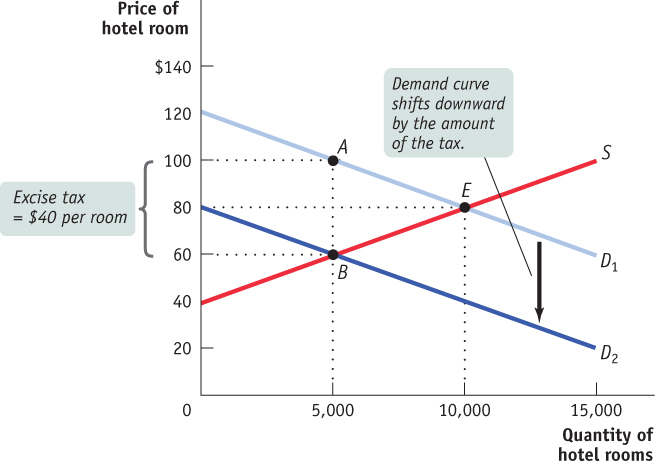

What would happen if the city levied a tax on consumers instead of producers? That is, suppose that instead of requiring hotel owners to pay $40 per night for each room they rent, the city required hotel guests to pay $40 for each night they stayed in a hotel. The answer is shown in Figure 50.7. If a hotel guest must pay a tax of $40 per night, then the price for a room paid by that guest must be reduced by $40 in order for the quantity of hotel rooms demanded post-

| Figure 50.7 | An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Guests |

If you compare Figures 50.6 and 50.7, you will notice that the effects of the tax are the same even though different curves are shifted. In each case, consumers pay $100 per unit (including the tax, if it is their responsibility), producers receive $60 per unit (after paying the tax, if it is their responsibility), and 5,000 hotel rooms are bought and sold. In fact, it doesn’t matter who officially pays the tax—

Tax incidence is the distribution of the tax burden.

This example illustrates a general principle of tax incidence, a measure of who really pays a tax: the burden of a tax cannot be determined by looking at who writes the check to the government. In this particular case, a $40 tax on hotel rooms brings about a $20 increase in the price paid by consumers and a $20 decrease in the price received by producers. Regardless of whether the tax is levied on consumers or producers, the incidence of the tax is the same. As we will see next, the burden of a tax depends on the price elasticities of supply and demand.

Price Elasticities and Tax Incidence

We’ve just learned that the incidence of an excise tax doesn’t depend on who officially pays it. In the example shown in Figures 50.5 through 50.7, a tax on hotel rooms falls equally on consumers and producers, no matter on whom the tax is levied. But it’s important to note that this 50–

What determines how the burden of an excise tax is allocated between consumers and producers? The answer depends on the shapes of the supply and the demand curves. More specifically, the incidence of an excise tax depends on the price elasticity of supply and the price elasticity of demand. We can see this by looking first at a case in which consumers pay most of an excise tax, and then at a case in which producers pay most of the tax.

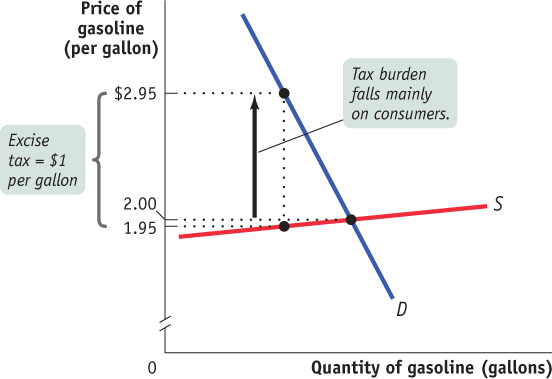

When an Excise Tax Is Paid Mainly by Consumers Figure 50.8 shows an excise tax that falls mainly on consumers: an excise tax on gasoline, which we set at $1 per gallon. (There really is a federal excise tax on gasoline, though it is actually only about $0.18 per gallon in the United States. In addition, states impose excise taxes between $0.04 and $0.37 per gallon.) According to Figure 50.8, in the absence of the tax, gasoline would sell for $2 per gallon.

| Figure 50.8 | An Excise Tax Paid Mainly by Consumers |

Two key assumptions are reflected in the shapes of the supply and demand curves in Figure 50.8. First, the price elasticity of demand for gasoline is assumed to be very low, so the demand curve is relatively steep. Recall that a low price elasticity of demand means that the quantity demanded changes little in response to a change in price. Second, the price elasticity of supply of gasoline is assumed to be very high, so the supply curve is relatively flat. A high price elasticity of supply means that the quantity supplied changes a lot in response to a change in price.

We have just learned that an excise tax drives a wedge, equal to the size of the tax, between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. This wedge drives the price paid by consumers up and the price received by producers down. But as we can see from Figure 50.8, in this case those two effects are very unequal in size. The price received by producers falls only slightly, from $2.00 to $1.95, but the price paid by consumers rises by a lot, from $2.00 to $2.95. This means that consumers bear the greater share of the tax burden.

This example illustrates another general principle of taxation: When the price elasticity of demand is low and the price elasticity of supply is high, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on consumers. Why? A low price elasticity of demand means that consumers have few substitutes and, therefore, little alternative to buying higher-

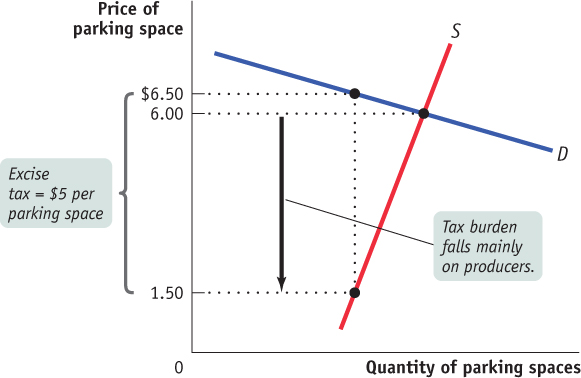

When an Excise Tax Is Paid Mainly by Producers Figure 50.9 shows an example of an excise tax paid mainly by producers: a $5.00 per day tax on downtown parking in a small city. In the absence of the tax, the market equilibrium price of parking is $6.00 per day.

| Figure 50.9 | An Excise Tax Paid Mainly by Producers |

We’ve assumed in this case that the price elasticity of supply is very low because the lots used for parking have very few alternative uses. This makes the supply curve for parking spaces relatively steep. The price elasticity of demand, however, is assumed to be high: consumers can easily switch from the downtown spaces to other parking spaces a few minutes’ walk from downtown, spaces that are not subject to the tax. This makes the demand curve relatively flat.

The tax drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. In this example, however, the tax causes the price paid by consumers to rise only slightly, from $6.00 to $6.50, but the price received by producers falls a lot, from $6.00 to $1.50. In the end, a consumer bears only $0.50 of the $5 tax burden, with a producer bearing the remaining $4.50.

Again, this example illustrates a general principle: When the price elasticity of demand is high and the price elasticity of supply is low, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on producers. A real-